-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning

2015; 1(1): 14-23

doi:10.5923/j.jalll.20150101.03

The Effect of Conversation Strategies on the Classroom Interaction: The Case of Turn Taking

Bahman Gorjian1, Parviz Habibi2

1Department of English, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran

2Department of English, College of Humanities and Social science, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

Correspondence to: Bahman Gorjian, Department of English, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Abadan, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper aimed to examine how signals of conversation strategies enhance the quality of speeches and conversations regarding the choice of the strategies (e.g., asking, proposing, checking, wait-time, turn taking, etc.). Movie clips from the New Interchange course book 1 were chosen and considered as the materials of the study. 90 participants were selected based on the homogeneity test at the pre-intermediate level and they were non-randomly divided into two control and experimental groups. The participants took a conversation exam as a pre-test and talk in pairs on various subjects. The pre-test scores were recorded at the beginning of treatment. During the treatment period, the experimental group received treatment of conversation strategies through explaining theses conversation strategies in the classrooms. The control group received traditional method of teaching conversations including role playing, class activities on different topics and the New Interchange Students’ book 1. The treatment lasted 15 sessions. Finally, they took a post-test on the same subjects they had in the pre-test. The reliability of scoring was calculated through Pearson Correlation analysis. Independent and Paired Samples t-test were used to determine the differences between the two group oral performances in the pre and post-tests. Results showed that the experimental group significantly outperformed the control group in terms of using more conversation strategies. Thus, this study suggests the explicit method of teaching conversation strategies in teaching conversations and oral performances.

Keywords: Interaction, Turn taking, Conversation strategies

Cite this paper: Bahman Gorjian, Parviz Habibi, The Effect of Conversation Strategies on the Classroom Interaction: The Case of Turn Taking, Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2015, pp. 14-23. doi: 10.5923/j.jalll.20150101.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The importance of conversation to our normative life is increasingly evident. Everything you do, say and present is a conversation or the opportunity for a conversation: what you say at a networking event, your website, your business card, your use (or misuse of social media), what you say at a meeting or event. All of these things are an opportunity to engage. According to [16], conversation is a form of interactive, spontaneous communication between two or more people who are following rules of politeness and ceremonies. It is polite give and take of subjects thought of by people talking with each other for company. A conversation works unpredictably for particular purposes since it is of a spontaneous nature [30].The concept of turn-taking covers a wide range of concern, not just a theoretical construction in the linguistic field of discourse analysis, but an important pattern in communicative events, governing speech-acts and defining social roles as it establishes and maintains social relationships. One cue associated with conversation strategies may cue the hearer to know that who have a turn to speak or make an utterance. Turn-taking is considered to play an essential role in structuring people’s social interactions in terms of control and regulation of conversations [13]. Therefore, the system of turn-taking has become object of analyses both for linguists and sociologists. As a matter of fact, turn-taking refers to the process by which people in a conversation decide who is to speak next. It depends on both cultural factors and smart cues. Turn-taking is one of the basic mechanisms in conversation, and the convention strategies vary between cultures and languages [11].Rich turn-taking is an available feature of human-spoken dialogue. A turn is the essential factor within conversation strategies, which is attached to a speaker. Each speaker takes turns within conversation. A speaker is someone creating some sort of utterance or speech act directed towards an audience of one or more people. Very generally, turn-taking in linguistics can be defined as the process through which the party doing the talk at the moment is changed [30]. Thus, turn-taking has to do with the allocation and acquisition of turns i.e. how turns are exchanged in a talk or conversation [5]. Turn allocation is about giving turns to the next speaker(s), while turn acquisition describes how turns are received. In other words, turn acquisition determines the kind of action(s) the next speaker(s) can or should take when it is his/her turn [20]. Conversation strategy is one of the basic mechanisms in conversation and the nature of conversation strategies is to promote and maintain talk. For smooth conversation strategy, the knowledge of both the linguistic rules and the conversational rules of the target language is required. According to [3], during a conversation, turn-taking may involve a cued gaze that prompts the listener that it is their turn or that the speaker is finished talking. There are two gazes that have been identified and associated with turn-taking. The two patterns associated with turn-taking are mutual-break and mutual-hold. Mutual-break is when there is a pause in the conversation and both participants use a momentary break with mutual gaze toward each other and then breaking the gaze, then continuing conversation again. This type is correlated with a perceived smoothness due to a decrease in the taking of turns. Mutual-hold is when the speaker also takes a pause in the conversation with mutual gaze, but then still holds the gaze as he/she starts to speak again [8].Conversation strategy as a pedagogical approach is at the core of teaching and learning in any subject. It comprises instructional and regulative components as it takes into account what kind of knowledge is to be exchanged and how it should be transmitted [6]. Since common attitudes, beliefs, and values are reflected in the way language is used [4], conversational rules vary in different cultures and different languages. One of the essential observations of conversational analysis is that, when conversing, participants obviously change their roles of speaker and hearer, i.e., they take turns [30].In the second language class, interactions between teachers and students serve as the main point for learning how to use the language. After the teacher asks a question, students mentally process their answers [1]. Conversation strategy could be the pause which the speaker thinks after questions and answers refer to the process by which people in a conversation decide who is going to speak next. It depends on both cultural factors and smart cues. In fact, the participants as [21] states look at language learning as an outcome of participating in discourse, particularly face-to-face interaction. This interpersonal interaction is thought of as a fundamental requirement of second language acquisition (SLA) [9].For teachers, the most widely useful advice is to match conversation strategies to the students’ preferences as closely as possible, regardless of whether these are slower or faster than what the teacher normally prefers. To the extent that a teacher and students can match each other’s pace, they will communicate more comfortably and fully, and a larger proportion of students will participate in discussions and activities. As with eye contact, observing students’ preferred conversation strategies is easier in situations that give students some degree of freedom about when and how to participate, such as open-ended discussions or informal conversations throughout the day [2].In order to begin a conversation, participants must form a relationship, and to do this they must in some sense be of the same order. Any relationship must necessarily be based on partial equivalence. There is a need to establish a temporarily-shared reality among participants. Participants, to some degree, must agree upon a world-view, a cosmology. Common ground-a set of propositions which make up the contextual background for the utterances to follow-must be established [17].Conversation is a type of discourse: it is spoken dialogic discourse. Thus, conversation analysis may be seen as a subfield of discourse analysis. Conversation analysis involves close examination of internal evidence within the (spoken) text. One type of conversation analysis is conversational ethno-methodology: Ethno-methodologists are primarily concerned with the tacit rules which regulate the taking-up by speakers of the running topic, and hence the change-over from speaker to speaker [30].Conversations follow rules of polite speech because conversations are social interactions, and therefore depend on social convention. Specific rules for conversation are called the cooperative principle. Failure to consider to these rules lead to eventually dissolves the conversation. Conversations are sometimes the ideal form of communication, depending on the participants' intended ends. Conversations may be ideal when, for example, each party desires a relatively equal exchange of information, or when one party desires to question the other. On the other hand, if maintain or the ability to review such information is important written communication may be ideal or if time-efficiency is most important, a speech may be preferable [2].Communicating, to whatever size of audience requires the speaker to encourage people to listen, engage, take on board what is being said and process that information with a view to doing something with it. People will only listen if they feel that the speaker is talking to them, interested in them, is speaking their language. Using the type of language they feel comfortable with is the key. Iranian students face the breaking down of conversations during conversing with other interlocutors. The main problem is that they sometimes do not follow the rules of conversation strategies appropriately. This study was to test the hypothesis that whether explicit teaching of these strategies could be helpful to enhance the learners’ oral performance in fulfilling the needs for an effective conversation [2].It is worth making an effort to talk through what is going on for you with someone you trust. Hence, this choice aimed to examine how signals or verbal turn-takings enhance the quality of speech and conversation, with respect choice of various conversation strategies. Movie clips or camera and teacher supervision were chosen and considered as the materials because they allowed constant reference to the context. The analysis of utterances in conversation strategies revealed that those statement-form utterances, utterances with a falling tone, and statement-form utterances with a falling tone mostly elicited turn-taking and backchannel responses and also resulted in a good and satisfied conversation [16].The importance of this study stems from the significance of the benefit of conversation strategies while talking in teaching English as a whole and in conversation in particular. This attempt may encourage the educational supervisors to modify their supervisory methods, too. Other researchers may be encouraged to carry out other studied dependent to this strategy. The current research aimed at showing this approach as a new trend for teachers and students. The most important goal of this research was to open a new door for teachers generally to be better teachers in teaching conversation and for learners to be better learners while learning speaking skill.It is expected by the end of this study, the research motivates Iranian teachers to change their beliefs and then their procedure in teaching conversation and in the long run the English teaching. The results of this study may help in enhancing and improving English conversation learning. But these kinds of studies can open some new doors and paths not only on English teaching but also in language teaching. However, as a nominal step, the current study can be regarded as a beneficial attempt in the field of conversation. With regard to the intended contents of the ongoing research the following research questions are raised:Can the conversation strategy of turn taking improve Iranian pre-intermediate learners’ speaking skills in conversations? The conversation system may actually vary between cultures and between languages [15]. In ordinary conversations, it is very rare to see any allocation of turns in advance. Participants naturally take turns. However, some account can be offered of what actually occurs there [14]. There is a set of rules that govern the turn-taking system, which is independent of various social contexts [25]: (a) when the current speaker selects the next speaker, the next speaker has the right and, at the same time, is obliged to take the next turn; (b) if the current speaker does not select the next speaker, any one of the participants has the right to become the next speaker. This could be regarded as self-selection; and (c) if neither, the current speaker selects the next speaker nor any of the participants become the next speaker, the current speaker may resume his/her turn. Conversation strategies are critical skills needed to develop cooperative play skills. They are required in life including conversation strategies, waiting to get someone’s attention, waiting while someone else is talking, waiting for a turn during play [26]. As boring as it is, taking turns and knowing how to wait goes a long way. Conversation strategies for language refers to the back and forth interaction whether it is with gestures, signs, sounds, or words.Because conversations need to be organized, there are rules or principles for establishing who talks and then who talks next. This process is called turn-taking. Conversation strategies are critical skills needed to develop cooperative play skills (Luu, 2010). [28]Turn-taking is usually considered to follow a simple set of rules, enacted through a perhaps more complicated system of signals. The most significant aspect of the turn-taking process is that, in most cases, it proceeds in a very smooth fashion [1]. Speakers signal to each other that they wish to either yield or take the turn through syntactic, pragmatic, and prosodic means. The organization of turn-taking provides "an intrinsic motivation for listening." As any given listener might be selected to speak next, s/he must cope with responding to the previous utterances. Goffman [25] observed a number of characteristics in conversation, among them: Variable turn order and size; variable distribution of turns; overlapping is common, but brief; and overlapping is promptly repaired (when two parties find themselves speaking at the same time, one of them will stop). Given these characteristics, it is obvious, according to Sacks et al., that turn-allocation techniques are being used. The current speaker may select a different next speaker, or either party may self-select [28].Turn-taking is usually considered to follow a simple set of rules, designed through a perhaps more complicated system of signals. The most significant aspect of the turn-taking process is that, in most cases, it proceeds in a very smooth fashion. Speakers signal to each other that they wish to either yield or take the turn through syntactic, pragmatic, and prosodic means. Goodwin [26] reported on a comparison of everyday conversation which is resembled to short-wave radio as to how the turn-taking is performed. The speaker provides an end-of-message signal, after which the hearer holds the channel, bringing about a change in the speaker/hearer roles. The difference between the two types of interaction is that, in a normal conversation, speakers benefit themselves of other means or mechanisms to provide that end-of-message signal. Goffman [25] observed a number of characteristics in conversation, among them: Variable turn order and size; variable distribution of turns; overlapping is common, but brief; and overlapping is promptly repaired (i.e., when two parties find themselves speaking at the same time, one of them will stop). Given these characteristics, it is obvious, according to Sacks et al., that turn-allocation techniques are being used. The current speaker may select a different next speaker, or either party may self-select.

1.1. What is a Turn?

- A turn is different from the situation where a speaker produces backchannel signals [30]. Backchannel signals, such as uh-huh, right, yeah, etc., are signals that the channel is still open, and they indicate at the same time that the listener does not want to take the floor. Duncan [18] also establishes a distinction between simultaneous turn and simultaneous talking. Instances of the first involve true overlapping, whereas instances of simultaneous talking do not always imply that the current hearer intends to take the turn; they might just be the result of backchannel signals overlapping with the current speaker’s turn. According to [22], turn taking definitions can be grouped in two main categories: Mechanical and interactional [23]. Goffman [25] says that a turn is the opportunity to hold the floor, not necessarily what is said while holding it. On the other hand, interactional definitions are concerned with what happens during the interaction, and take into consideration the intention of the turn taker. Edelsky [22] points out that speakers are more concerned with completing topics than structural units. Therefore, she defines turn as instances of on-record speaking, with the intention of conveying a message.

1.2. Speaking Skill

- "Speaking" is the delivery of language through the mouth. To speak, we create sounds using many parts of our body, including the lungs, vocal tract, vocal chords, tongue, teeth and lips [29]. When we learn our own (native) language, learning to speak comes before learning to write. In fact, we learn to speak almost automatically. It is natural. But somebody must teach us to write. It is not natural. In one sense, speaking is the "real" language and writing is only a representation of speaking. However, for centuries, people have regarded writing as superior to speaking. It has a higher "status". This is perhaps because in the past almost everybody could speak but only a few people could write. Modern influences are changing the relative status of speaking and writing. Speaking is a communication skill that enables a person to verbalize thoughts and ideas [19]. There are two instances when such a skill is required and these are: interactive and semi-interactive. In the first instance (interactive), this would involve conversations with another person or group of persons whether face-to-face or over the phone, wherein there is an exchange of communication between two or more people. In the second instance, semi-interactive happens when there is a speaker and an audience such as in the case of delivering a speech, wherein the speaker usually does all the talking, while the audience listens and analyzes the message, expressions, and body language of the speaker. Every single day, we are given opportunities to speak [2].At home, the interaction with family members and neighbors and ask driving directions from passersby. We converse with the waitress at the local pub. At work, talk to colleagues and superiors and in addition discuss business issues and concerns during business meetings [13]. People with less average communication skills, particularly speaking skills, may have difficulty in gatherings, including social, personal, or business-related. The speaker does not know how to put his thoughts and ideas into words or he simply does not have enough confidence to speak in the presence of other people. Regardless of what may be the reason for this, it leads to one thing: ineffective communication. And a person who cannot communicate effectively would find it difficult to strike a good impression on others, especially on their superiors [2].The whole of human history is built upon communication. From the first story told in prehistoric times through the mass media of today, verbal communication has built the foundation of who we are, where we came from, and what we hope to become. Throughout time, many orators, philosophers, and educators have tried to capture the essence of human communication [25]. Although a true understanding of the complexity of communication takes years of examination, I have tried to offer a brief highlight of some of the major contributors.

1.3. The Systematic of Turn-Taking

- In all interactions there are rules and practices that structure turn-taking: who can speak when, how long they can speak for and what they can say. Bakeman and Gottman [12] detailed examination of sequences of interactions led to the development of a system of rules (a systematic) that govern all turn-taking. Sacks et al. noted that usually only one person speaks at a time, yet the speaker changes frequently with minimize overlapping or gap between changing the roles of the speakers. Bakeman and Gottman's [12] systematic turn taking includes an iterative hierarchy of rules that manage speaker change. Firstly, where it would be relevant for there to be a change in speaker, the current speaker can select the next speaker and they are morally obliged to take the turn. If the current speaker has not nominated the next speaker, then another speaker can self-select to take the next turn and the person who speaks first takes the turn. Finally, if the next speaker has not been nominated or has not self-selected, then the current speaker continues with the turn. These rules then apply again at the next place where it is relevant for the speaker to change. Participants in interactions have been shown to orient to these rules in interactions and in a variety of contexts. However, certain activities or institutional contexts can place further constraints on the sequential structure of turn-taking. Teachers may also have some preformed ideas about that student will participate in whole class interactions. Both the teacher and the students will have goals tied to the classroom context, which they will orient to in their interactions. Additionally, whole class interactions include several participants, so there is an audience for any interaction. This aspect goes some way to explaining the frequent use of nomination in changing speaker in order to minimize the possibility of overlap of turns. In formal classrooms, it is the teacher who asks questions and the pupils who answer.This pre-allocation means that the teacher, as questioner, can take long turns, constructed with a variety of turn types until the teacher produces a question that is recognized as such by the students. The student as answerers, are constrained to give an answer to the teacher’s question and their turn ends as soon as an answer is given. The dominance of teachers asking questions and students answering questions is often discussed in terms of the power and dominance of the teacher [7].When you are talking with others, there are a number of elements in the conversation that commonly appear. Understanding these allows you to better control the conversation and ensure the other person is better able to respond. You can also analyze the other person's speech as they talk and cope with any misuse or mistakes in their structures [26] Among the following conversation strategies, turn taking instruction could enhance learners' interaction in the classroom. Thus the research question tried to ask whether turn taking instruction develop learners' interaction and oral communication significantly. • Turn taking: When you take the floor• Asking: Engaging and seeking information.• Informing: Giving information.• Asserting: Stating something as true.• Proposing: Putting forward argument.• Summarizing: Reflecting your understanding.• Checking: Testing understanding.• Building: Adding to existing ideas.• Including: Bringing in others.• Self-promotion: Boosting oneself.• Supporting: Lending strength.• Disagreeing: Refusing to agree.• Avoiding: Refusing to consider argument.• Challenging: Offering new thoughts to change thinking.• Attacking: Destruction of their ideas.• Defending: Stopping their attacks.• Blocking: Putting things in the way of their arguments.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- In the present study, the population was 120 male students who studied English as a foreign language in Azad University in Abadan. Non-random sampling method was used for the selection of these participants. They took part in a homogeneity test based on Oxford Placement test at the pre-intermediate level to homogenize the participants. Then ninety students whose scores were one standard deviation above and one standard deviation below the mean were chosen as the participants of the present study. The level of the placement test was designed for pre-intermediate learners. They were non-randomly divided into two groups, one experimental and one control. Each group included thirty participants. Experimental group has benefited from conversation strategies while the control group used the traditional way of talking in the conversation sessions or role playing and they were exposed to the strategies implicitly. The participants were within the age range between 20 and 31.

2.2. Instrumentation and Materials

- In order to accomplish the objectives of the present study, the following instruments were employed:The Oxford Placement Test for the pre-intermediate learners was used to determine the homogeneity of the participants. This test featured 50 multiple-choice items covering vocabulary and grammar. The allocated time was sixty minutes to answer. Pre-test and post-test were designed by giving the learners the topics used in the course book and their conversation was recorded to test their conversation strategies. Their presentations were rated by two raters. The main sources of data collection for this study were direct classroom observation and recording conversation between 2 or 3 minutes in each small group conversing related topics. New Interchange: Book 1, fourth edition [29]: It consists of ten units. The materials used in this study included reading and topics concerned with conversation strategy while students are interacting together and proposed the topics and managed the conversations.

2.3. Procedure

- To accomplish the purpose of the study, first 90 male students who were studying English language translation were selected from Azad University of Abadan, and then a homogeneity test based on Oxford Placement Test was administered. The pre-intermediate level was observed through calculating their scores gained on the homogeneity test. With regards to this, they were non-randomly divided into two groups. The two groups, 45 learners each, included one experimental and one control group. They met for one hour and a half, once a week. In the first session of the course a pre-test containing working on the given topics was administered to the participants before treatment in order to determine how well the participants know the conversation strategies in performing oral performances before treatment. Then the conversations in pairs or peers were recorded and scored by two raters to estimate their inter-rater reliability of the scores. The Pearson Correlation Analysis was used to calculate the reliability index as (r=.857). The treatment was based on the actual lesson instructions and technical terms on the topics regarding conversation strategies in the sessions. In each session, the first hour was allotted to lesson instruction and the rest to explain and teaching the conversation strategies in the experimental group. The same procedure was used in the control group but the conversation strategies were taught implicitly. The whole research took place in language institution classroom circumstance. To motivate and encourage the participants to pay enough attention and to play more active role in the research program, they were told that the purpose of the extra instruction was to improve their quality in conversation and how got the meaning of the partner intention through conversation strategies while their conversation. The entire research project took place in ten sessions. In the experimental group, 10 topics were chosen regarding to conversation with change of the roles between teacher and participants or between the participants. During the sessions of instruction, 90 minutes each, 60 minutes were allocated to main performances and the 30 minutes of the time dealt with discussion on the conversation strategies e through showing some clips within the book. The experimental groups were considering conversation strategies and while the other one were in a traditional way and ordinary conversation in which the above strategies were taught without awareness in an implicit method. In order to teach and investigate on the effect of the conversation strategies in the experimental classes, the following phases were carried out:In the first session, first of all, it was supposed to teach main lesson and then describe and explain about conversation strategies as clarification the point and get the student familiar to conversation strategies and how they should get turn to answer the questions and in their conversations through showing some clips within the book and clarify some signals and cues which showed as conversation strategies. In each session, after reading the passage, the teacher presented the students with the challenging conversation strategies to ask questions and answers of the students and also in their conversation together. When the teacher is the current speaker, then firstly the teacher can nominate a student to be the next speaker. If the teacher does not nominate the next speaker, then the teacher must continue the turn. If a student is the current speaker then they select the next speaker and the teacher takes the turn. If the student does not select the next speaker then anyone can self-select as next speaker, with the teacher taking the turn if they self-select. If the teacher or another learner does not self-select then the student continues the turn.The students were asked individually to come the board and interact with teacher based on considering the conversation strategies and also in pairs between students as show the point and clarify the conversation strategies by changing the role speaker and hearer directly and tangible as sample to other students until the time let us.The control group received the same strategies implicitly and was taught in traditional and ordinary conversation. The participants in the control group conversed with no conversation strategies in the classroom interactions and conversation, whereas the experimental group got benefit of conversation strategies while talking to each other in the form of conversation. In reality, the basic aim behind the study was exploring the impact of conversation strategies upon conversation enhancement and satisfaction from what has been spoken as a concluding remark. These conversations on the post-test were recorded in each group and rated by two raters to estimate the inter-rater correlation (i.e. Pearson correlation analysis). The pre-test reliability index was (r=.796) and for the post-test, it was (r=. 901) which showed appropriate indexes. Both the pre-test and the post-test were performed as part of the classroom evaluation activities under the supervision of the instructor.

2.4. Data Analysis

- Having data collected, the researcher processed the data using the statistical package for social sciences (version 17). Independent Samples t-test was used to determine the differences between the two groups’ pre and post-tests.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Pre-Test

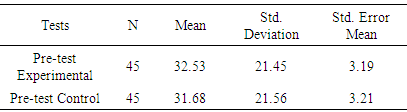

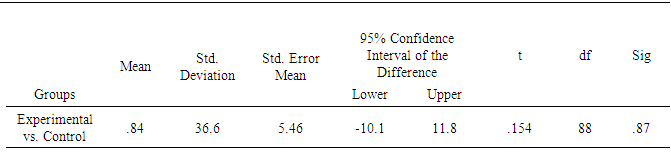

- At the beginning of the study, two groups were given a pre-test which their statistical data is presented in Table 1.

|

|

3.2. Results of Post-Test

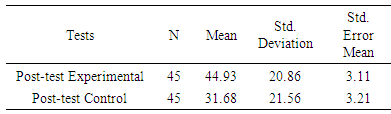

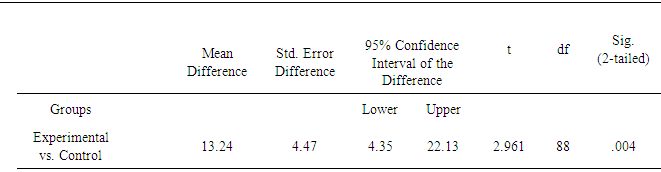

- Descriptive statistics of the post-tests’ oral performance in the pre-test was calculated in the Table 3.

|

|

4. Discussion

- This section elaborates on the results and findings presented in the previous chapter. To discuss the results of the research, the research question raised earlier in the study will be referred to as follows:Does turn taking instruction develop learners' interaction and oral communication significantly? Results of the study showed that the control and experimental groups were almost homogeneous based on the pre-test scores. To answer the research question, an Independent Sample t-test was conducted to find if there were any meaningful differences between the results of the experimental and control groups in the post-test. The analysis of covariance rejected the null hypothesis revealing a significant difference between conversation strategies users and nonusers. The main aim of learning a language is to use it in communication in its spoken or written forms. Classroom interaction is a key to reach that goal. It is the collaborative exchange of thoughts, feelings or ideas between two or more people, leading to a mutual effect on each other. Through interaction, students can increase their language store as they listen to or read authentic linguistic material, or even output of their fellow students in discussions, skits, joint problem-solving tasks, or dialogue journals. In interaction, students can use all they possess of the language-all they have learned or casually absorbed-in real life exchanges.Therefore, in line with the above mentioned statements and the present study, it could be strongly argued that Conversation strategies activities strategy instruction can significantly influence EFL language learners’ developing conversation. Simply, this study represents a preliminary effort to empirically examine the effect of conversation strategy of turn taking at the university level. The results of this study are matched with [8] who emphasize the importance of interaction among human beings and using language in various contexts to “ negotiate” meaning, or simply stated, to get one idea out of your head and into the head of another person and vice versa. The results showed that there was not a significance difference among students‘ performance in pre-test, but in contrast there was a significant difference among the performances of the two groups in the post-test. Thus, it could be observed that students who received conversation strategies instruction got better marks and their performance was better than the other group. By looking at the groups’ means the results of post-test by Independent Sample t-test revealed that experimental group had the greatest improvement in their scores based on their conversations. The learners of experimental group after ten sessions outperformed the other groups. Therefore, the second research null hypothesis was rejected. The reasons behind this result could be discussed in terms of the effectiveness of conversation strategies on the quality of conversation in classroom interaction. Results showed a significant difference with between the experimental and control group. The above mentioned reasons might be the explanation of why the experimental group did better than the control group. The fact that experimental group outperformed the control group indicates that use of conversation strategies in conversation let the students to think more and more about utterances and lead to mutual understanding and also give and ask opinion to be qualified the conversation. Based on the result section, there are significant differences between the two groups. The results of the post-test may show the difference between the two groups in case of the use of conversation strategies semantic strategies. The group of experimental instruction outperformed the group of control instruction. It shows that the use of conversation strategies ameliorate performance of speakers and lead to mutual understanding in conversation. Thus the first null hypothesis was not accepted. As far as it is evident, the results of the present thesis investigation highlighted the remarkable role of conversation strategies in improving learner conversations learning achievement. Based on the results of statistical calculations pursued during this process, the null hypothesis study was rejected and it was concluded that there is a significant difference between the groups’ performances due to the given treatment. Further, the study has revealed that the conclusion of conversation strategies programs are more effective in enhancing conversation than the traditional methods for developing Iranian EFL learners’ oral performances.The people can create a new world, but not separately. It needs communities to do, and to be heard in safety and courage no matter what the circumstances. Turn-taking systems can provide strong motivations for non-speakers to listen closely to the current-speaker: only by keeping track of upcoming transition-places can a hopeful next-speaker know when to speak; and there is always the possibility that one may be called upon by the current-speaker. Turn-taking plays an important role in the dynamics of human social interactions [12]. It may feel effortless, but turn-taking relies on a complex mix of contextual, verbal, and gestural cues that unfold over time. A conversation strategy for language refers to the back and forth interaction whether it is with gestures, signs, sounds, or words.The present study raised a number of questions requiring further research in the area of conversation strategies and its influence on conversation development. First of all, it is of importance to confirm more normative data with typically developing learners for conversation strategies and conversation strategies. Similar research in respect of this trend might be valuable, especially with respect to interference programs in conversation classes. Turn-taking as pedagogical strategy which has shown turn-taking is a complex process which is influenced by various factors including classroom power relation and enhances the quality of conversation between students.Furthermore, it is important to determine whether similar results in terms of conversation strategies and conversation strategies trends would be found when studying a larger plenty of participants. It would also be beneficial to study samples outside of Iran to determine if the same outcome applies not only for non native English speaking learners but also to children speaking British, Australian and American English or languages other than English. Moreover, conversation strategies trends regarding conversation require further investigations. Although a positive correlation with conversation was observed in the current study. Future findings might contribute to a better understanding of the fact that some students benefit more from interference programs and, therefore, show better treatment outcomes than others.We know that conversation is a great source for our everyday stories. Think a little about some of the most important moments in your life and about the relationships you have. The foundation of nearly all of these is conversations. When we are learning about one another, we are listening and enjoying simple moments together. Undoubtedly, conversation plays an important role in our life. As human we need communication to express our needs, thoughts and opinions to other and conversation is important in communication. In reality, relationship is spoiled due to lack in conversation. A conversation has the ability to solve most of the life issues. Turn-taking in conversation is an important skill for speakers to develop. Communication is a give and take process much like taking turns. Of course, many speakers are still learning to share and taking turns with their partners. However, a conversation strategy to help promote language skills looks a little different. Turn-taking for language refers to the back and forth interaction whether it is with gestures, signs, sounds, or words. This study described the participant, setting, instruments, and materials. It contained the research design, procedures to conduct the testing, description of the treatment, and outline of the data collected. The performing of measures to support social validity, internal validity, and external validity were described. The test results, treatment data, and observations of using the pre-reading activities were provided in this study. Quantitative data collected before, during, and after treatment show that this trend was useful and significant improvement learners’ conversation was recorded during the treatment period. Most speakers have difficulties in sharing conversation strategies while speaking to each other. It was supposed that if conversation strategies are into account, the quality of conversation will improve. This investigation aimed at examining how signals or verbal turn-takings enhance the quality of speech and conversation in EFL conversations, with respect to the choice of various conversation strategies. Through conducting the current project, it was revealed the experimental group getting benefits of conversation strategies outperformed the control group.

5. Conclusions

- Informal verbal interaction is the core matrix for human social life. A mechanism for coordinating this basic mode of interaction is a system of turn-taking that regulates who is to speak and when. Yet relatively little is known about how this system varies across cultures. The anthropological literature reports significant cultural differences in the timing of turn-taking in ordinary conversation. We tested these claims and results showed that in fact there are striking universals in the underlying pattern of response latency in conversations. The experimental group outperformed their counterpart, i.e. control group. Simply put, the intended trend proved to be efficient and useful on improving the quality of learners’ conversation.This reality was manifested after conducting an orally conversation test in which the scores of the experimental group after analyses were far better than that of the scores of the participants in the control group. Thus, in the current report, the conversation strategies are proved to ameliorate learners’ conversation. All of the languages show the same factors explaining within-language variation in speed of response. However, find differences across the languages in the average gap between turns. The beliefs that conversations are to be conceptualized as sequences of discrete actions are not universally held. For a minority, turn-taking serves not an explanatory role but an operational one. Since the concept supports analysis of conversational substance, it can be used in investigating how physical properties of speaking and silence contribute to conversational events. When people communicate in face-to-face interaction they take turns speaking [18]. The system’s main function is to sequential information exchange between two or more communicating groups and ensures efficient transmission. The phenomenon of turn-taking seems quite easy to define. The talk of one party bounded by the talk of others constitutes a turn, with turn-taking being the process through which the party doing the talk of the moment is changed. This work is a first step towards building conversation strategies time models that enable virtual characters to decide when they should take the turn in conversation.The result of Independent Samples t-test analysis implies that conversation strategies had a significant impact on experimental group performance in conversation aspect. In simple terms, conversation improvement of Iranian EFL learners could be attributed to conversation strategies instruction. The results of the study also indicated that the members of the experimental group achieved better results in the conversation than their counterparts in the control group did. In sum, those in the experimental group became more aware when they used conversation strategies. The application of conversation strategies in the classroom opened new prospects for the subjects, which motivated them to do extra activities outside in the classroom specially with regard to conversation. Conversation strategies instruction had positive effects on enhancing in conversation. The basic question in this study was whether or not Conversation strategies instruction enhances EFL grammar. The results are straightforward and make a strong argument in favor of considering Conversation strategies with Iranian EFL learners.

6. Implications of the Study for Teaching Conversation

- When the teacher and pupils are orienting to their institutional roles through their participation in the constrained turn-taking rules. In formal classroom interactions, the teacher usually has some preformed idea or plan of what should be said and done in the lesson. Teachers may also have some preformed ideas about which students will participate in whole class interactions. Both the teacher and the pupils will have goals tied to the classroom context, which they will orient to in their interactions. Additionally, whole class interactions include several participants, so there is an audience for any interaction. This aspect goes some way to explaining the frequent use of nomination in changing speaker in order to minimize the possibility of overlap of turns [10]. The rules of turn-taking are not tangible physical objects but they provide opportunities and constraints for interactional actions. There has already been much debate about the constraints that turn-taking imposes on whole class discussions and the implications these may have on teaching and learning, Conversation analytic approaches to the analysis of classroom discourse have revealed a relationship between the structure of discourse and the actions of participants. However, only a detailed analysis of the implications of this relationship in language learning has been undertaken [27]. The structure of turn-taking in classrooms offer opportunities for the teaching and learning of good conversation and how to interact together which are not available in the structure of turn-taking in ordinary conversations. The results of this research may be useful for both teachers and students. As some classes have been observed, not only is the focus of teachers on vocabulary but also they teach reading traditionally with little attention to conversation. It can be a good study to find the roots and reasons of this problem, but the present research aims to work on the effect of conversation strategies on Iranian EFL conversation quality so that teachers can change their path of thinking, working and teaching conversation at least for the speaking of EFL learners. It is surprising that even the teachers don’t have the weakest clue what their method of teaching conversation is. Communication is the heart and soul of the human experience. It is a natural phenomenon that we start speaking what everybody speaks around us. Teachers of English are recommended to use appropriate conversation strategies in activities on the learners’ conversations and pay attention to the students’ participation. When teaching a language we actually have two purposes: insure fluency and accuracy in all language skills. Fluency is the ability to speak fluently whereas accuracy is the ability to speak with correct grammar structures, such as correct use of verb forms, phrasal verbs, prepositions, etc. To communicate intelligibly and to make sense with each sentence a learner should know the principles of the target language. The lexicon of a language is the most prominent aspect which, however, loses its remarkable value without grammar.However, administrations and supervisors are recommended to do the following: (a) Provide teachers with training courses to enhance using appropriate conversation strategies techniques in conversation activities in their classes, (b) Prepare and distribute instructional materials that increase awareness of using various strategies and emphasizes on the significance and necessity of using appropriate conversation strategies techniques in teaching English conversation, (c) Conduct workshops that aim at familiarizing teachers of how to teach conversation by using conversation strategies trends, (d) Encourage teachers to exchange visits and hold periodical meeting to discuss new methods of teaching such as conversation strategies, and (e) Connect schools with local society especially universities and educational centers to enhance making conversations among English clubs.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML