Sheraliyeva Dildora Nodir kizi1, Tokhtaboyeva Yulduzkhon Abdusattorovna2

1Phd Student, Namangan State University, Namangan, Uzbekistan

2Doctor of Biological Sciences, Associate Professor, Kimyo International University in Tashkent Branch Namangan, Namangan, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

As salinity levels continue to rise worldwide, this poses a serious threat to agriculture. Such areas, including those in Uzbekistan, cover a significant amount of land. Studying the algal flora of these areas and utilizing its significance for agricultural purposes is one of the pressing tasks. In this regard, our research was conducted on cotton fields growing on saline soils in the Papsky and Mingbuloksky districts of the Namangan region of the Fergana Valley in Uzbekistan. Using molecular genetic analysis, we were able to identify five species of microalgae and cyanobacteria in samples collected from all regions. These species are adapted to saline soils and have been recorded as indicator species in cotton fields.

Keywords:

Cyanobacteria, Microalgae, Diversity, ITS2, Soils, Salinity

Cite this paper: Sheraliyeva Dildora Nodir kizi, Tokhtaboyeva Yulduzkhon Abdusattorovna, Morphological and Molecular-Genetic Analysis of Some Species of Algaflora in Salted Soils of the Fergana Valley, International Journal of Virology and Molecular Biology, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2026, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.ijvmb.20261501.01.

1. Introduction

In Uzbekistan, the classification of saline soils includes types such as salt marshes and salt flats, which differ in terms of the depth of the salt deposits and their composition. Saline soils have a high concentration of water-soluble salts in the upper layer, whereas in saline soils, salts are located deeper and are present in the soil particle complex, especially in the sodium-rich horizon [FAO/ORG.2018]. Saline soils contain mineral salts in quantities that are harmful to plants. Crop growth begins to be inhibited when the salt content in the soil profile exceeds 0.25% of the soil mass [15].Saline soils cover a vast area of Uzbekistan, accounting for a significant portion of the land fund in such important agricultural regions as cotton-growing areas. Salinization, which occurs on irrigated land, has various causes, but regardless of its origin, salinization always has a negative impact on plant growth and development and on the properties of the soil itself. It destroys soil structure, impairs water-physical, physicochemical, and biological properties, affects microbiological activity and other properties, thereby causing soil degradation and plant death [15].In recent years, in many cotton-growing regions, particularly in Central Fergana, the soil reclamation and ecological condition of irrigated soils has deteriorated sharply, the level of mineralized groundwater has risen above the “critical” depth, processes of salinization and desertification have intensified, and the content of organic matter (humus) and plant nutrients, as well as the fertility and productivity of irrigated lands, have declined [15].

2. Materials and Methods of Research

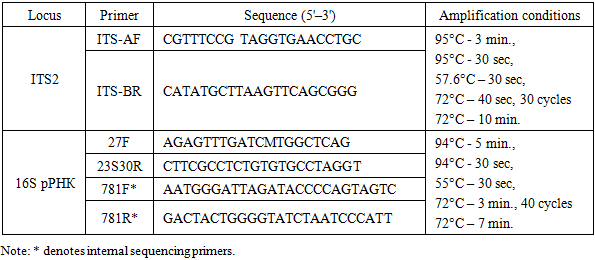

Description of the study areas. The Fergana Valley is an intermontane basin in the mountains of Central Asia, approximately 300 km long and up to 170 km wide, divided between three countries: Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. The northern part of the Fergana Valley is home to the Namangan region of the Republic of Uzbekistan, which has a continental climate (dry summers and mild, wet winters). The average temperature in January is +4 °C, and in July +35 °C. Precipitation in the plains ranges from 135 mm to 370 mm per year, and in the foothills from 460 mm to 630 mm (Tukhtaboeva et al. 2025). Two areas within the region were studied: Papsky and Mingbuloksky, and five soil-algal samples were taken from cotton fields growing on saline soils. Below are the characteristics of the sampling points:1. Papskie Polya (Papski District). Altitude above sea level: 650–660 m. The soils are medium loamy typical gray-zems, washed to varying degrees and covered with gravel in places. The air temperature on the day of sampling was 12°C with a humidity of 47%. Two mixed soil-algal samples were collected from two locations: 1 sample – 40°77'24.20'‘N 70°96'08.56’'E.Isolation and cultivation of microalgae and cyanobacteria strains. To isolate strains from soil, we used the cumulative culture method with subsequent sowing on BG-11 agar medium. Next, through repeated streaking and isolation of individual colonies using a Pasteur pipette, algologically pure cultures were obtained [1]. The strains were then cultivated on solid BG-11 nutrient medium with nitrogen (pH = 7.0; agar 1.4%) in a climate chamber under standard conditions (temperature 23–25°C, light 60–75 μmol photons m–2 s–1, photoperiod 12 h). The strains studied were deposited in the All-Russian Collection of Microorganisms (VKM) under numbers VKM Al-505, 514, 515, 517, and 518.Light microscopy. The morphology and life cycles of algologically pure cultures were studied using light microscopy with a Leica DM750 microscope (Germany). The results of the observations were documented with photographs taken using a Leica Flexacam C3 color digital camera (Germany). The observation period ranged from 1 to 12 weeks. During morphological identification of microalgae strains, diacritical features such as thallus organization type, cell shape and size, chloroplast number and type, pyrenoids presence, mucilage presence and thickness, reproduction method, etc. were taken into account. During morphological identification of cyanobacterial strains, diacritical features such as thallus organization type, trichome width and polarity, cross-septum lacing, presence and type of mucous membranes, cell color, size, and shape, apical cell differences, etc. were taken into account. Leica Application Suite X software was used for morphometric measurements. To compare sizes, 100 cells from each strain were measured. Selected articles were used for morphological and molecular genetic identification of the green microalgae strain [4,5,6,7,8,9], cyanobacteria [11]. This study is based on the algae system adopted in the international electronic database Algae Base [2].Total DNA extraction, amplification, purification, and sequencing of amplicons. Total DNA was extracted from the strain using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A ready-made Screen Mix-HS (Eurogen, Russia) was used for amplification. The conditions and primers for amplification of ITS2 [3] and the 16S rRNA gene [12,13,14] are shown in Table 1.Table 1. Primers and amplification conditions for target loci

|

| |

|

Detection of the target PCR product was performed electrophoretically in a 1% agarose gel. For further purification of amplicons from the gel, the Cleanup Standard kit (Eurogen, Russia) was used. Sequencing was performed by the commercial company Eurogen (Russia).Molecular phylogenetic analysis. For molecular genetic identification of strains, a search for homology of ITS2 nucleotide sequences and the 16S rRNA gene was performed using the BLASTn algorithm in GenBank NCBI (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Sequence selection was based on criteria of maximum relatedness, read quality (without degenerate and unknown nucleotides), read length, and belonging to type species and authentic collection strains. The dataset of strains VKM Al-505 and 514 consisted of 52 sequences, including an outgroup, Neochloris aquatica UTEX B 138. The dataset of strains VKM Al-517 and 518 consisted of 21 sequences, including an outgroup, Crassifilum sonorensis SON62. The VKM Al-515 strain dataset consisted of 58 sequences, including an outgroup - Chlorococcum hypnosporum SAG 213-6, Chlorococcum echinozygotum SAG 213-5, and Chlorococcum infusionum SAG 10.86.Multiple alignment was performed in BioEdit using the ClustalW algorithm. Nucleotide substitutions were selected using the IQ-TREE web server (http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at/), focusing on the minimum value of the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method with the IQ-TREE web server, with the stability of phylogenetic tree nodes assessed using the ultra-fast bootstrap procedure (1000 replicates) and visualized. The values of SH-aLRT / ultra-fast bootstrap (UB) support are indicated as statistical support for the tree nodes. Differences between nucleotide sequences were characterized using genetic differences, measured as the percentage of nucleotide mismatches in pairwise comparisons of aligned sequences, calculated using the MEGA 11 program. The nucleotide sequences obtained were deposited in GenBank NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under numbers PV432757, PV640460, PV432766, PV432767, and PV642431.

3. Results and Discussion

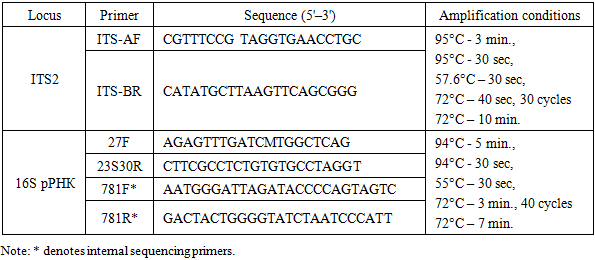

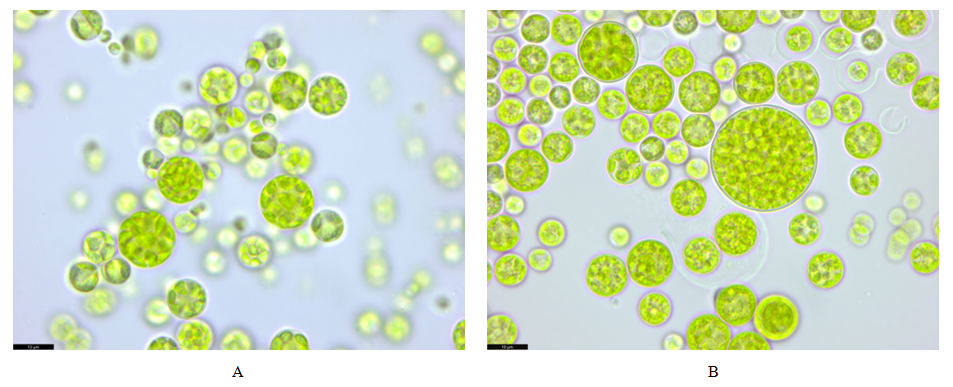

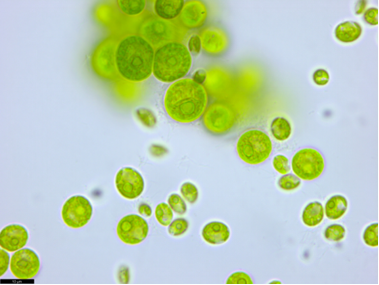

Both strains had Bracteacoccus-like morphology.The cells of strain VKM Al-505 were single, spherical, 3.8‒15.5 μm in diameter (Fig. 1A). The cell wall does not thicken noticeably with age. Young cells contain 2–4 chloroplasts, while mature cells contain numerous chloroplasts without pyrenoids. Reserve substances – orange lipid droplets. Asexual reproduction by the formation of autospores (from 4 pieces in the mother cell), zoosporogenesis was not observed in culture.The cells of strain VKM Al-514 were single or in aggregates, spherical, 5.3‒27 μm in diameter (Fig. 1B). The cell wall is quite strong, but does not thicken noticeably with age. Young cells contain 2–4 chloroplasts, while mature cells contain numerous chloroplasts without pyrenoids. Reserve substances – orange lipid droplets. Asexual reproduction by the formation of autospores (from 4 pieces in the mother cell). Autospores often mature inside the sporangium wall and, after its destruction, can form cell aggregates. Zoospore formation has not been observed in culture. | Figure 1. Morphology of Bracteacoccus sp.VKM Al-505 (A) and 515 (B) strains. Scale bar: 10 μm |

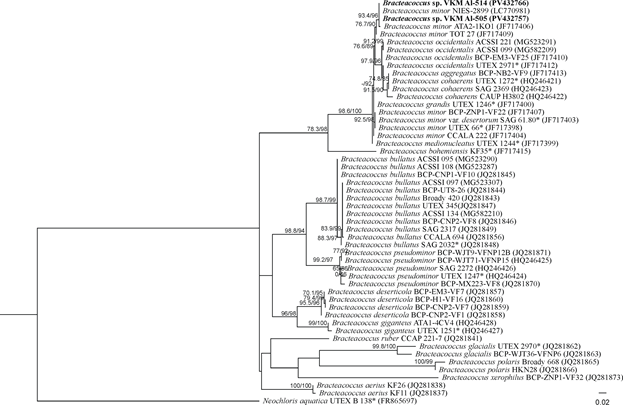

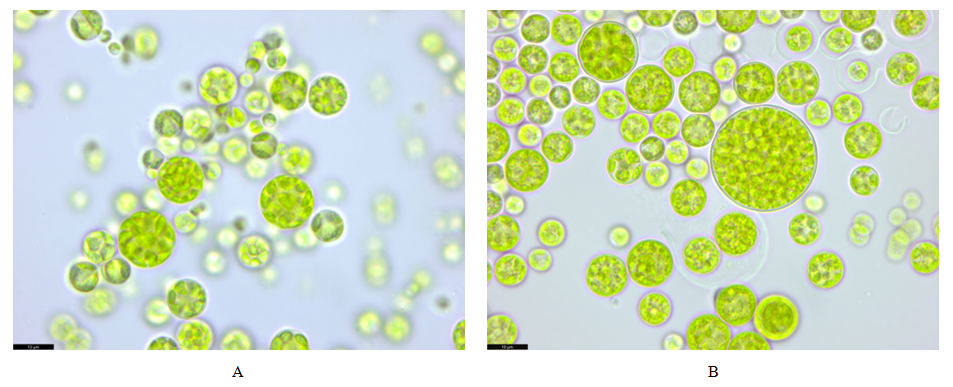

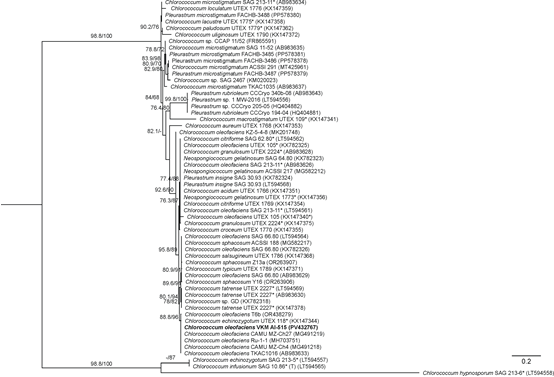

Molecular genetic analysis of the variable marker ITS2 showed the identity of ITS2 strains VKM Al-505, VKM Al-514, and the non-authentic strain Bracteacoccus minor NIES-2899, which, together with other non-authentic strains B. minor ATA2-1KO1 and B. minor TOT 27, were grouped together with a fairly high level of statistical support within the genus Bracteacoccus (Fig. 2). | Figure 2. Rooted phylogenetic tree of green microalgae of the genus Bracteacoccus, constructed using the ML method, based on the sequences of the internal transcribed spacer ITS2 (350 bp). SH-aLRT/UB values are given as statistical support for tree nodes. SH-aLRT and UB values less than 70% are not shown. Nucleotide substitution model: TIM2+F+G4. Symbols: * − authentic strains, studied strains are highlighted in bold |

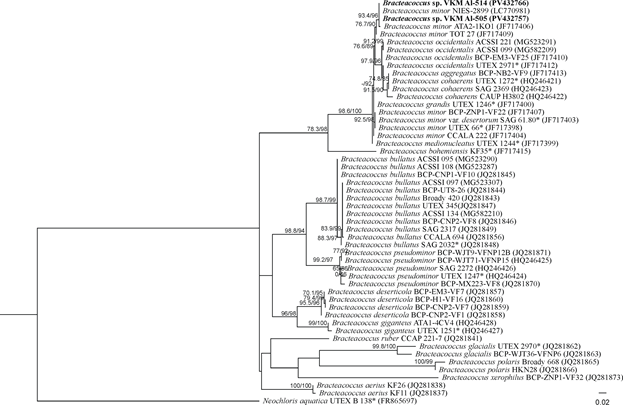

The genetic distance between the listed strains ranged from 0 to 0.7, which, in accordance with the intraspecific threshold for ITS2 <2% (Hoshina, 2014), indicates that they belong to the same species. However, the authentic strain B. minor UTEX 66 occupies a different, unrelated position on the phylogenetic tree, forming an independent cluster. The genetic distance between it and the studied strains was 1.7%, between the studied strains and authentic cultures of other species belonging to the same cluster: B. grandis UTEX 1246 - 1.4%, B. medionucleatus UTEX 1244 - 1.8%, B. cohaerens UTEX 1272 - 2.5%, B. occidentalis UTEX 2971 - 3.2%. Thus, the strains were identified as Bracteacoccus sp. due to the fact that this cluster needs to be revised.The VKM Al-515 strain had spherical or ellipsoidal young cells. Mature vegetative cells are usually spherical, up to 22 μm in diameter, containing one parietal cup-shaped chloroplast, in mature cells pierced with holes and cracks, one pyrenoid with a continuous starch envelope located in the thickened part of the chloroplast, and one nucleus (Fig. 3). | Figure 3. Morphology of the Chlorococcum oleofaciens VKM Al-515 strain. Scale bar: 10 μm |

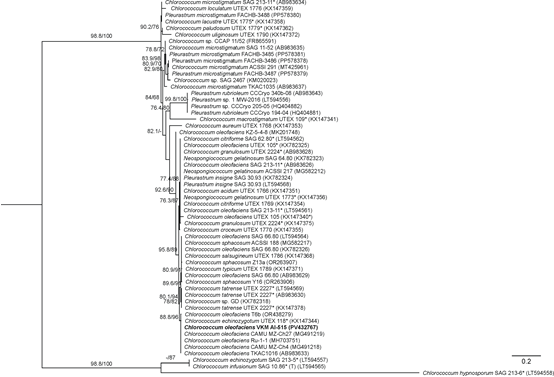

With age, the cell wall thickens. Asexual reproduction occurs with the help of 2–16 aplanospores or stationary zoospores of ellipsoidal shape, up to 7.5 μm in length and up to 4.4 μm in width, with a parietal chloroplast and a central pyrenoid, without papillae. Autospores are spherical and are held together for a long time by the stretched maternal membrane.ITS2 analysis showed that strain VKM Al-515 belonged to the same group as non-authentic strains of Chlorococcum oleofaciens (Fig. 4). The genetic distance from the authentic strain UTEX 105 was 0.4%, and from SAG 213-11 - 2.1%, with the latter two being subcultures and not expected to have genetic differences between them. Following the proposed intraspecific threshold for ITS2 <2% (Hoshina, 2014), it can be assumed that these strains belong to the same species. | Figure 4. Rooted phylogenetic tree showing the taxonomic position of strain VKM Al-515, constructed using the ML method based on the sequences of the internal transcribed spacer ITS2 (274 bp). SH-aLRT/UB values are given as statistical support for tree nodes. SH-aLRT and UB values less than 70% are not shown. Nucleotide substitution model: TIM2e+G4. Designations: * − authentic strains, (T) – type species, the strain under study is highlighted in bold |

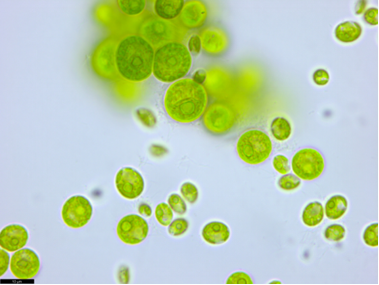

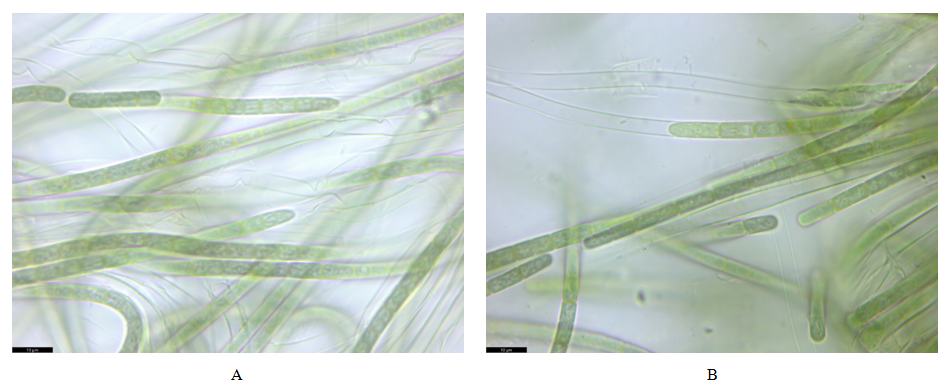

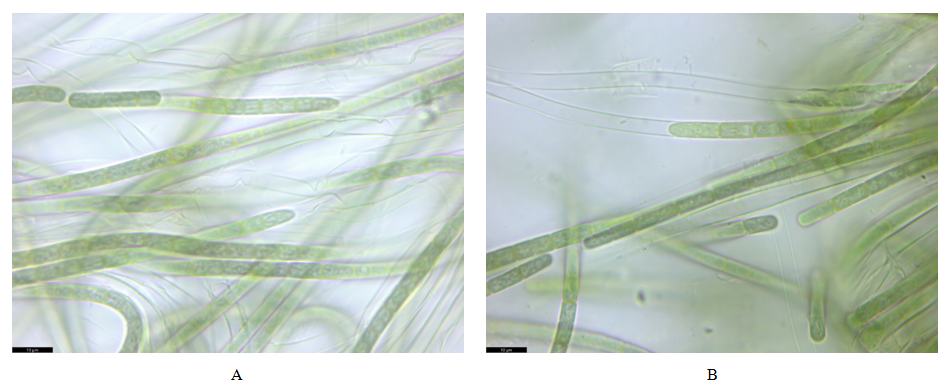

Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that Chlorococcum oleofaciens, together with C. citriforme, C. sphacosum, and C. tatrense, were transferred to Pleurastrum insigne (Sciuto et al., 2023). However, we did not observe the short branched, single-row or multi-row filaments, sarcoid packets, tetrads, and pairs of cells characteristic of the genus Pleurastrum in culture, so we identify this strain as Chlorococcum oleofaciens.The cyanobacterial strain VKM Al-517 was characterized by gray-green trichomes, mostly straight, 3.9-4.6 μm wide, slightly constricted at the transverse septa, not tapering towards the ends (Fig. 5A). The sheaths are colorless and contain one trichome each. Cell length 4.4-7.7 µm. Apical cells rounded or conical, sometimes capitate, with calyptra. Sliding type of movement. Reproduction by hormogonia. The strain differs from the type description of Allocoleopsis franciscana in having narrower homopolar trichomes (Moreira et al., 2021).The cyanobacterial strain VKM Al-518 had olive-green trichomes, mostly straight, 4.1-4.8 μm wide, laced at the transverse septa, not tapering towards the ends (Fig. 5B). The vaginas are thin, colorless, and contain one trichome each. The cells are 4.5-8.8 μm long. The apical cells are elongated and broadly conical. The filaments are mobile. Reproduction occurs by fragmentation with the help of non-crevice cells. | Figure 5. Morphology of Allocoleopsis franciscana strains VKM Al-517 (A) and 518 (B). Scale bar: 10 μm |

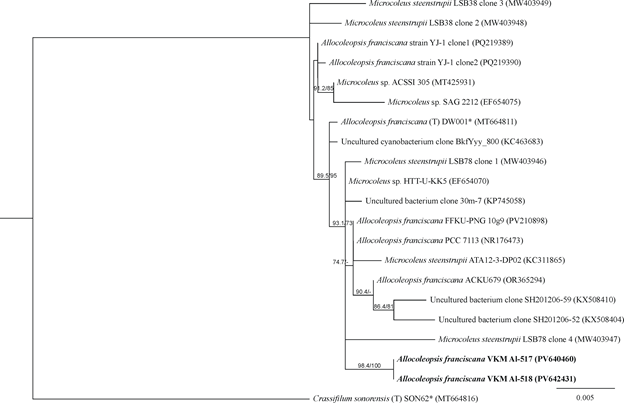

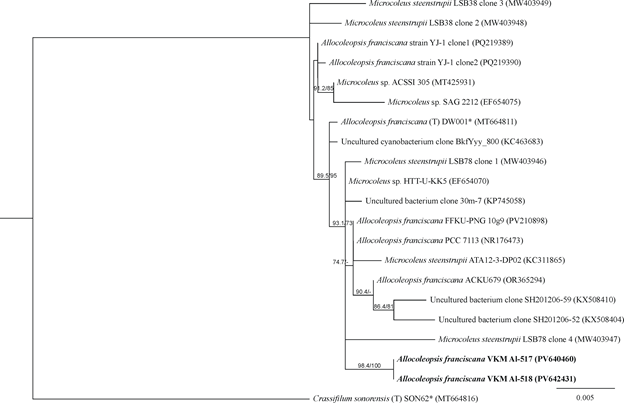

Both strains differ from the type description of Allocoleopsis franciscana in having narrower homopolar trichomes (Moreira et al., 2021).Molecular genetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene showed clustering of the two strains studied in the Allocoleopsis clade (Coleofasciculaceae, Coleofasciculales), including the authentic strain A. franciscana (Fig. 6). The differences between them were 0%, and compared to the authentic strain, 0.63%, which allowed strains VKM Al-517 and VKM Al-518 to be identified as A. franciscana. It is noteworthy that representatives of this species are usually found in biological soil crusts, but rarely in hot deserts (Moreira et al., 2021), while our strains were isolated from soils in an arid region. | Figure 6. Rooted phylogenetic tree of cyanobacteria of the genus Allocoleopsis, constructed using the ML method, based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (1493 bp). SH-aLRT/UB values are given as statistical support for tree nodes. SH-aLRT and UB values less than 70% are not shown. Nucleotide substitution model: HKY+F+I. Designations: * − authentic strains, (T) – type species, the studied strain is highlighted in bold |

4. Conclusions

Thus, for the first time, morphological and molecular genetic analyses were used to study the diversity of microalgae cultivated on saline soils in the northern part of the Fergana Valley (Uzbekistan). Two strains of green microalgae (Chlorophyta) and one strain of cyanobacteria (Cyanobacteria) were detected. Only one species of microalgae and cyanobacteria has been identified within the species: Chlorococcum oleofaciens and Allocoleopsis franciscana. One other strain belongs only to the genus and requires further research: Bracteacoccus sp. The low species diversity of microalgae and cyanobacteria can be explained by both the high salinity and low fertility of the surrounding soils and the characteristics of the agrotechnical approach, which reveals only part of the true diversity of microorganisms. The research conducted may serve as a basis for the further development of highly functional consortia based on microalgae and cyanobacteria to improve and sustainably develop low-productivity, salinated, and degraded terrestrial ecosystems.

References

| [1] | Temralieva A.D., Mincheva E.V., Bukin Yu.S., Andreeva A.M. Modern methods for the isolation, cultivation, and identification of green algae (Chlorophyta). Kostroma: Kostroma Printing House, 2014. 215 p. |

| [2] | Guiry MD, Guiry GM (2025) AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, University of Galway. https://www.algaebase.org. Accessed 28 Febrary 2025. |

| [3] | Johnson J.L., Fawley M.W., Fawley K.P. The diversity of Scenedesmus and Desmodesmus (Chlorophyceae) in Itasa State Park, Minnesota, USA // Phycologia. 2007. V. 46. P. 214–229. doi: 10.2216/05-69.1. |

| [4] | Hoshina, R. DNA analyses of a private collection of microbial green algae contribute to a better understanding of microbial diversity. BMC Res Notes 7, 592 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-592. |

| [5] | Fucikova K., Flechtner V.R., Lewis L.A. Revision of the genus Bracteacoccus Tereg (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) based on a phylogenetic approach // Nova Hedwigia. 2012. V. 96. N. 1-2. P. 15-59. |

| [6] | Fuciková K., Rada J.C., Lewis L.A. The tangled taxonomic history of Dictyococcus, Bracteacoccus and Pseudomuriella (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) and their distinction based on a phylogenetic perspective // Phycologia. 2011. V. 50. N. 4. P. 422-429. |

| [7] | Tereg E. Einige neue Grünalgen // Beihefte zum Botanischen Centralblatt. 1923. V. 39. P. 179-195. |

| [8] | Starr R.C. A comparative study of Chlorococcum meneghini and other spherical, zoospore-producing genera of the Chlorococcales // Indiana University Publications Science. 1955. V. 20. P. 1-111. |

| [9] | Novis, P.M. & Visnovsky, G. 2012. Novel alpine algae from New Zealand: Chlorophyta. Phytotaxa 39: 1-30. |

| [10] | Fucíková C., Lewis L.E. Intersection of Chlorella, Muriella and Bracteacoccus: Resurrecting the genus Chromochloris Kol et Chodat (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) // Fottea. 2012. 12(1). P. 83–93. |

| [11] | Moreira, C., Fernandes, V., Giraldo-Silva, A., Roush, D., and Garcia-Pichel, F. (2021). Coleofasciculaceae, a monophyletic home for the Microcoleus steenstrupii complex and other desiccation-tolerant filamentous cyanobacteria. J. Phycol. 57, 1563–1579. doi: 10.1111/jpy.13199. |

| [12] | Strunecký O., Elster J. & Komarek J. 2010. Phylogenetic relationships between geographically separate Phormidium cyanobacteria: is there a link between north and south polar regions? - Polar Biology 33: 1419–1428. |

| [13] | Flechtner, V.R., Boyer, S.L., Johansen, J.R. & DeNoble, M.L. (2002). Spirirestis rafaelensis gen. et sp. nov. (Cyanophyceae), a new cyanobacterial genus from arid soils. Nova Hedwigia 74: 1-24. |

| [14] | Sciuto, K., Wolf, M.A., Mistri, M. & Moro, I. (2023). Appraisal of the genus Pleurastrum (Chlorophyta) based on molecular and climate data. Diversity 16(650): 1-31. |

| [15] | Turdaliev Zh.M., Mansurov Sh.S., Akhmedov A.U., Abdurakhmonov N.Yu. Salinity of Soil and Groundwater in the Fergana Valley // Scientific Review. Biological Sciences. 2019. No. 2. Pp. 10-15. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML