-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Virology and Molecular Biology

p-ISSN: 2163-2219 e-ISSN: 2163-2227

2025; 14(6): 132-138

doi:10.5923/j.ijvmb.20251406.09

Received: Oct. 3, 2025; Accepted: Oct. 25, 2025; Published: Nov. 3, 2025

Comparison of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Escherichia Coli Strains Isolated from Broiler Chickens and Patients with Acute Intestinal Infections

Tashpulatova M. K.1, 2, Abdurakhimov A. A.3, 4, Rakhmatullaev A. I.3, 4, Tashmukhamedova Sh. S.2, Abdukhalilova G. K.1

1Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Epidemiology, Microbiology, Infectious and Parasitic Diseases of the Republic of Uzbekistan

2National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

3Institute of Biophysics and Biochemistry, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

4Center for Advanced Technologies, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Tashpulatova M. K., Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Epidemiology, Microbiology, Infectious and Parasitic Diseases of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

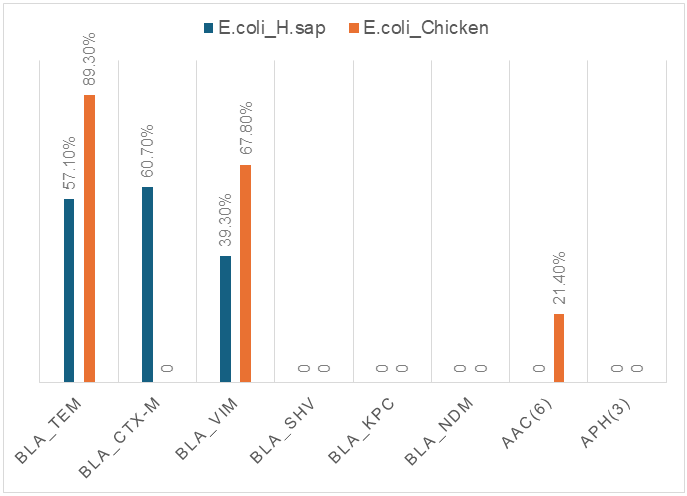

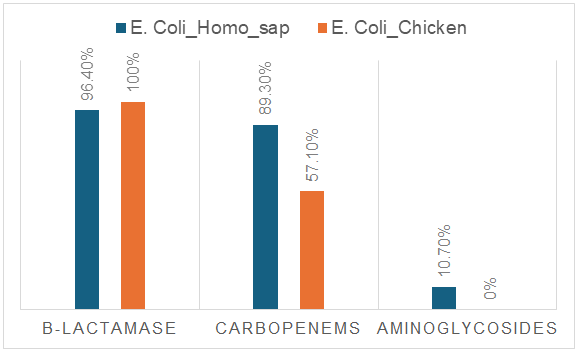

Amid the growing global threat of antibiotic resistance, the spread of resistant Escherichia coli strains in both clinical and veterinary settings is a matter of particular concern. In this study, we conducted a comparative analysis of E. coli strains isolated from patients with acute intestinal infections and from broiler chickens. The research was carried out at the Antimicrobial Resistance Center laboratory of the Republican Specialized Scientific-Practical Medical Center for Epidemiology, Microbiology, and Infectious and Parasitic Diseases of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Special attention was given to determining antimicrobial resistance profiles using the disk diffusion method, as well as to identifying resistance genes associated with aminoglycoside and β-lactam antibiotics through molecular techniques. Using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), we detected and characterized β-lactamase genes (bla_TEM, bla_SHV, bla_CTX-M, bla_VIM, bla_NDM, bla_KPC) and aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes (aac(6')-II, aph(3')-VI). The bla_CTX-M gene was detected at a high frequency (60.7%) among strains isolated from patients with acute intestinal infections, whereas bla_TEM was the most prevalent in broiler chicken isolates (89.3%). A strong correlation was observed between genotypic and phenotypic resistance profiles, underscoring the critical role of molecular surveillance in clinical microbiology. The obtained data reveal a high prevalence of multidrug resistance and confirm the circulation of shared genetic determinants among Escherichia coli strains isolated from both patients with acute intestinal infections and broiler chickens. This underscores the need for a comprehensive, integrated approach to antimicrobial resistance surveillance within the framework of the One Health concept.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, Strains, Acute intestinal infection, Antimicrobial resistance

Cite this paper: Tashpulatova M. K., Abdurakhimov A. A., Rakhmatullaev A. I., Tashmukhamedova Sh. S., Abdukhalilova G. K., Comparison of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Escherichia Coli Strains Isolated from Broiler Chickens and Patients with Acute Intestinal Infections, International Journal of Virology and Molecular Biology, Vol. 14 No. 6, 2025, pp. 132-138. doi: 10.5923/j.ijvmb.20251406.09.

1. Introduction

- Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is now recognized as one of the most serious threats to global public health. Gram-negative bacteria - particularly Escherichia coli - are of special concern due to their remarkable ability to rapidly adapt to antimicrobial therapy through the acquisition and horizontal transfer of resistance genes. Of particular clinical significance are E. coli strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases. These enzymes confer resistance to key classes of β-lactam antibiotics, including extended-spectrum cephalosporins and carbapenems - often considered last-resort treatments for severe infections. Such resistance mechanisms severely complicate the management of infections in both human and veterinary medicine and facilitate the spread of resistant pathogens through food chains, the environment, and direct contact [1].The study of Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans with acute intestinal infections (AII) and from livestock—particularly broiler chickens—has become increasingly relevant, as these reservoirs are likely interconnected within the framework of the One Health concept. Antibiotic resistance genes encode proteins that enable bacterial survival in the presence of antimicrobial agents. The primary resistance mechanisms include: Antibiotic hydrolysis (e.g., β-lactamases such as bla_TEM, bla_SHV, bla_CTX-M, bla_KPC); Target modification (e.g., altering antibiotic binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit, aac(6')-II); Active efflux of the drug (efflux pumps); Changes in cell membrane permeability; Antibiotic modification (e.g., acetylation, phosphorylation — aph(3')-VI, adenylation).Resistance genes may be located both on the bacterial chromosome and on mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids (e.g., bla_TEM, bla_NDM, bla_CTX-M). Gene transfer can occur: Horizontally — between different bacteria (via conjugation, transformation, or transduction); Vertically — from parent cell to progeny during cell division.The mobility of these resistance genes renders the antimicrobial resistance problem particularly acute, as pathogens can rapidly acquire resistance even in the absence of prolonged antibiotic exposure.Molecular detection of resistance genes such as bla_TEM, bla_SHV, bla_CTX-M, bla_VIM, bla_NDM, bla_KPC, aac(6')-II, and aph(3')-VI represents an important tool for monitoring the spread of resistance and assessing the risk of transmission across different populations.

2. Materials and Methods

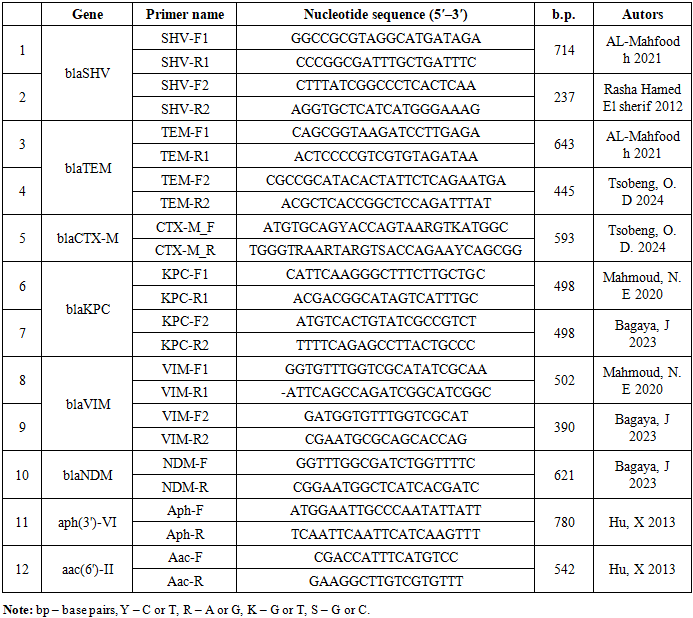

- To achieve the stated objectives, the research was conducted in the laboratory of the Center for Antimicrobial Resistance (CAMR) at the RSSPMCEMIPD within the framework of the state grant PZ: 20170928351 “Development of a system for predicting and preventing adverse effects of alimentary factors on human health based on the determination of resistance phenotypes and common patterns of microbial susceptibility to antimicrobial agents in patients with diarrhea and in farm animals” (January 3, 2018 – December 31, 2020).The study of morphological, tinctorial, and biochemical properties of E. coli strains was carried out in accordance with WHO protocols [2]. Biochemical activity was determined by inoculation of cultures into semi-liquid media containing various carbohydrates, alcohols, and amino acids: glucose, mannitol, dulcitol, urea, arabinose, xylose, citrate, acetate, malonate, phenylalanine, and lysine. Indole formation was determined in broth using the Morel reagent method [3]. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the disk diffusion method, and the interpretation of results was carried out according to the EUCAST recommendations (2021, version 11.0) [4]. Mueller–Hinton agar (GEETA PHARMA, India) and antibiotic discs manufactured by Liofilchem S.r.l. (Italy) were used throughout the testing. The susceptibility of E. coli was tested against the following antimicrobial agents: β-lactams (ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime, ceftriaxone, imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, doripenem), and aminoglycosides (amikacin). For internal quality control of the experiments, the reference strain E. coli ATCC 25922 was used.The resistance mechanisms of E. coli strains to β-lactam and aminoglycoside antibiotics were studied using molecular genetic methods: PCR with electrophoretic detection. Genes encoding β-lactamases of broad and extended spectrum families (bla_SHV, bla_TEM, bla_CTX-M), carbapenemases (bla_KPC) and metallo-β-lactamases (bla_NDM, bla_VIM), as well as aminoglycoside resistance genes (aph(3')-VI, aac(6')-II) were detected.DNA extraction. Bacterial DNA was isolated using the thermal lysis method with sterile water. Five to six colonies from a 24-hour culture of the test microorganism, grown on solid agar medium, were transferred into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube containing 1,000 µL of nutrient broth. The suspension was vortexed briefly to disperse the cells and then centrifuged (Microspin 12, Biosan) at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes to pellet the bacteria. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 400 μL of sterile water and vortexed (MX-S, DLAB). Tubes were incubated in a dry block thermostat (TDB-120, Biosan) for 10 min at 95°C, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 5 min. The supernatant containing released DNA was transferred to a clean tube. DNA quality and concentration were measured using a BioSpec-nano spectrophotometer.PCR analysis of E. coli resistance genes (bla_SHV, bla_TEM, bla_CTX-M, bla_KPC, bla_VIM, bla_NDM, aph(3')-VI, aac(6')-II), was performed using lyophilized GenePak™ PCR Core reagents (LLC “Izogen Laboratory,” Russia). Each reaction tube contained lyophilized Taq DNA polymerase and dNTPs. The final reaction volume was 20 µL, including the added template DNA.DNA from the reference strain Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a negative control. Amplification reactions were performed using a Veriti™ Dx 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems). Gene-specific primers targeting the following resistance determinants were employed: bla_SHV, bla_TEM, bla_CTX-M, bla_KPC, bla_VIM, bla_NDM, aph(3')-VI and aac(6')-II (primer sequences and reaction conditions are provided in Table 1).

|

3. Results and Discussion

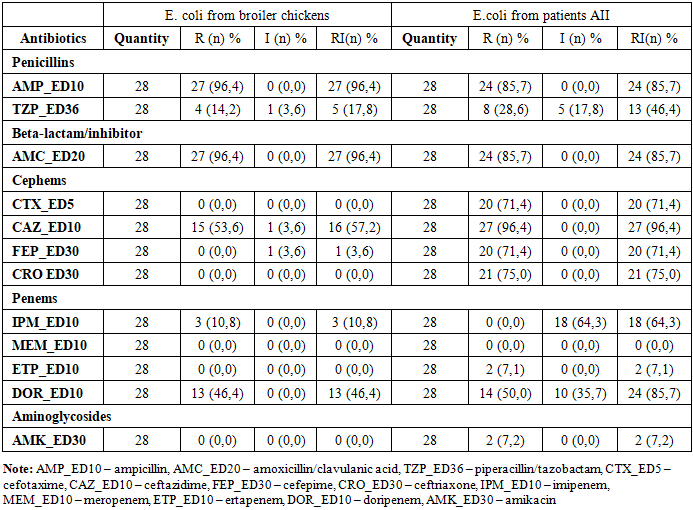

- A total of 28 Escherichia coli strains were isolated from the intestinal contents of broiler carcasses collected during slaughter at Farm No. 1 in Tashkent. Using random sampling, 10 carcasses from apparently healthy birds (mean body weight: 1,000 ± 100 g) were selected, and each was processed for bacteriological analysis on the day of collection. Additionally, 28 E. coli strains were isolated from stool samples of patients hospitalized with acute intestinal infections (AII) at the Republican Specialized Scientific-Practical Medical Center for Epidemiology, Microbiology, and Infectious and Parasitic Diseases (RSSPMCEMIPD).To assess possible differences in the frequency of resistance between E. coli strains isolated from broilers and those from AII patients, strains with moderate and high resistance levels were combined into a single category, “non-susceptible.” Poultary isolates (Table 2) showed higher resistance to ampicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid — 96.4% each, compared with human isolates (85.7% and 93.1%, respectively). In contrast, human-derived strains exhibited significantly higher resistance to third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins: cefotaxime (71.4%), ceftriaxone (75.0%), cefepime (71.4%), and ceftazidime (96.4%). Notably, cephalosporin resistance was largely absent in poultry isolates, with the exception of ceftazidime (57.2%). Differences were also noted in resistance to carbapenems. Marked differences were also observed for carbapenems. Among human isolates, resistance to imipenem and doripenem was 64.3% and 85.7%, respectively, whereas in broiler isolates, these values were considerably lower (10.8% and 46.4%, respectively).

|

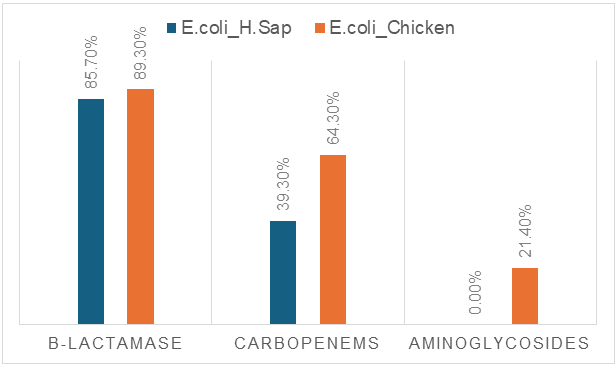

| Figure 1. Comparative chart of resistance genes in AII patients and broiler chickens |

| Figure 2. Microbiological analysis of resistance of E. coli strains to three groups of antimicrobial agents |

| Figure 3. Molecular genetic analysis of resistance of E. coli strains to three groups of antimicrobial agents |

4. Conclusions

- Statistically significant differences were revealed in the prevalence of resistance genes responsible for β-lactamase and aminoglycoside resistance in E. coli strains isolated from AII patients and broiler chickens. A high degree of concordance was observed between genotype and resistance phenotype, confirming the effectiveness of molecular genetic screening methods for rapid and accurate monitoring. The results obtained emphasize the necessity of coordinated control of human and animal health within the framework of the “One Health” concept.Our study covered the main and most prevalent resistance genes; however, for a more comprehensive picture, it should also be considered that additional resistance genes exist, such as AmpC, OXA, GES, qnr, rmt, and others.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML