-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Virology and Molecular Biology

p-ISSN: 2163-2219 e-ISSN: 2163-2227

2025; 14(6): 118-122

doi:10.5923/j.ijvmb.20251406.06

Received: Sep. 29, 2025; Accepted: Oct. 23, 2025; Published: Oct. 31, 2025

Analysis of Charantin Steroid Glycoside from Momordica Charantia Extract and Investigation of Its Intranasal Therapeutic Potential in Type 2 Diabetic Rats

Ibragimov Zafar Zokirjonovich, Abdurakhimov Sunnatilla Alisher ugli, Ibragimova Elvira Akhmedovna, Saatov Talat Saatovich, Bakhodirov Khusen Quvondiq ugli

Laboratory of Metabolomics of the Institute of Biophysics and Biochemistry at the National University of Uzbekistan named After Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

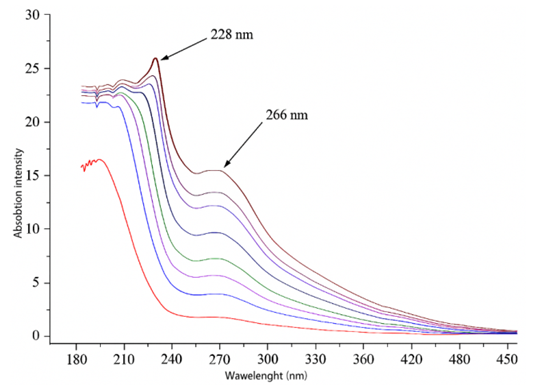

This study aimed to identify the characteristic steroidal glycoside charantin in the fruit extract of Momordica charantia using UV spectrophotometric analysis. Absorbance values were recorded at different concentrations of the extract. The 10% solution exhibited a distinct absorption peak at 254 nm, whereas the 50% solution showed a peak around 266 nm. A consistent increment in absorbance with increasing concentration of extract was observed, indicating the presence and progressive accumulation of charantin in the extract. These findings confirm that UV spectrophotometry is an effective method for the detection of charantin and validate its characteristic spectral properties in ethanolic extracts of Momordica charantia. To investigate its biological activity, thirty rats with experimentally induced type 2 diabetes mellitus were used. The animals were maintained on a high-calorie diet containing 0.2% cholesterol and 2% margarine for 8 weeks, reaching a body weight of 470±20 g. Intranasal administration of liposome-encapsulated charantin for five consecutive days led to a marked decrease in blood glucose levels—from 7.57 mmol/L before treatment to 5.33 mmol/L after treatment.

Keywords: Momordica Charantia, Charantin, Steroidal Glycoside, UV Spectrophotometry, Ethanolic Extract, Phytochemical Analysis, Model animals, Absorption Peak, Antidiabetic Compound

Cite this paper: Ibragimov Zafar Zokirjonovich, Abdurakhimov Sunnatilla Alisher ugli, Ibragimova Elvira Akhmedovna, Saatov Talat Saatovich, Bakhodirov Khusen Quvondiq ugli, Analysis of Charantin Steroid Glycoside from Momordica Charantia Extract and Investigation of Its Intranasal Therapeutic Potential in Type 2 Diabetic Rats, International Journal of Virology and Molecular Biology, Vol. 14 No. 6, 2025, pp. 118-122. doi: 10.5923/j.ijvmb.20251406.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

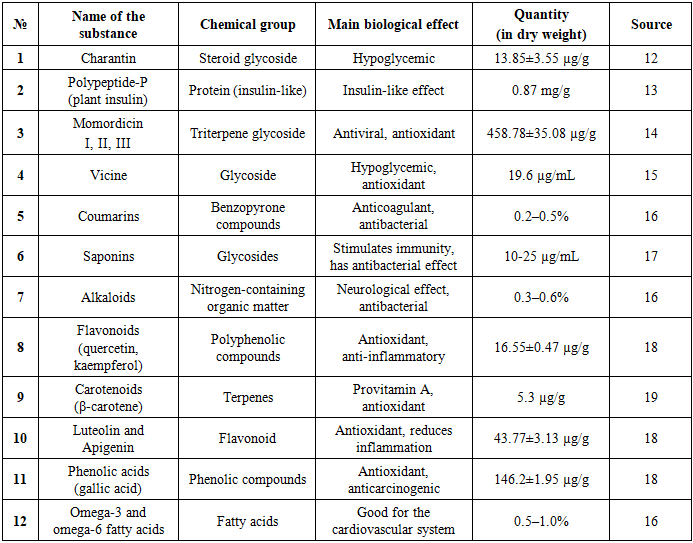

- It is well known that the fruits of the Momordica charantia plant, or bitter melon (sometimes called Indian pomegranate), have scientifically proven health benefits [1-3]. This plant has been used in traditional medicine since ancient times, especially for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. In recent years, with the identification of new phytochemicals in Momordica charantia, scientific research has intensified into the mechanisms of its antidiabetic, antioxidant, antitumor and antimicrobial action [1-3] (Table 1).

|

2. Materials and Methods

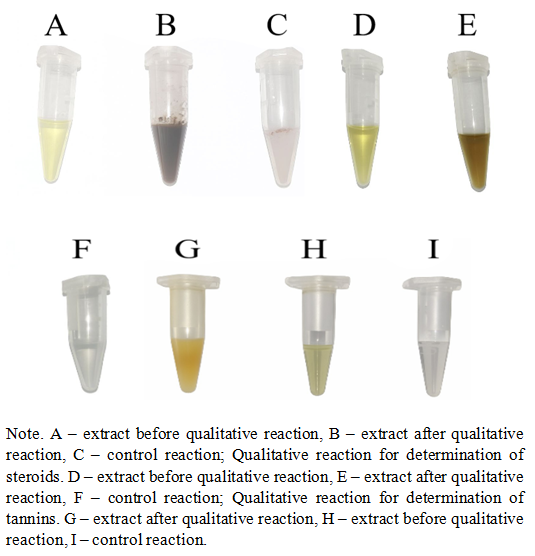

- The object of the study was ripe parts of M. charantia fruits. For purification, they were washed in special solutions. Then, divided into small pieces, dried in a “TС-1/80” thermostat and ground to a homogeneous powder. Extraction processes was performed from the prepared dry raw materials using the alcohol extraction method. The resulting extract was concentrated on a “RE 100-Pro Dlab” vacuum rotary evaporator, obtaining a viscous extract. Extract solutions of various concentrations were prepared, filtered and solid residues were separated in a minicentrifuge. To determine the composition of the extract, a “Nano One Ultra Micro UV-Vis” spectrophotometer (in the range of 200-800 nm) was used and characteristic spectra were determined. Qualitative reactions of charantin identification were carried out using the Molisch reagent for carbohydrates, the Lieberman-Burkhardt method for steroids and the lead acetate method for tannins. Statistical analysis of the obtained results was performed using the “EpiCalc 2000” program.30 adult rats (male, 10–12 weeks old) weighing 390 ± 20 g were used in this study. All animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions (22 ± 2 °C, 12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was induced by maintaining the animals on a high-calorie diet containing 0.2% cholesterol and 2% margarine for 8 weeks, resulting in stable hyperglycemia and increased body weight. The study was conducted at the Metabolomics Laboratory of the Institute of Biophysics and Biochemistry under the National University of Uzbekistan in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and international guidelines for laboratory animal care and use.Liposomal formulations containing M. charantia extract were administered intranasally to diabetic rats at a standardized dose once daily for five consecutive days.Blood glucose concentrations were measured using the Cypress Diagnostics Glucose Kit (Cypress Diagnostics, Belgium), an in vitro diagnostic medical device designed for the quantitative determination of glucose in citrate plasma free from hemolysis and turbidity. For analysis, blood samples were collected from the tail vein into citrate-containing microtubes. Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes, and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 510 nm, and glucose concentration was expressed in mmol/L.

3. Results

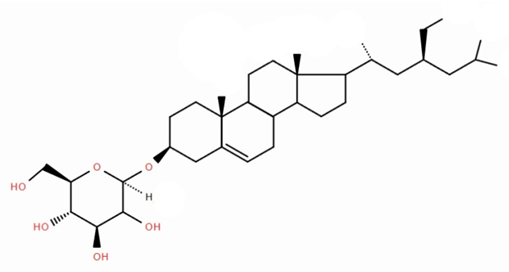

- In recent years, the methods for isolating charantin have been significantly improved. Among them, ultrasonic extraction (UE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) and microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) have shown high efficiency compared to traditional methods [7-9].Charantin consists of two components: β-sitosterol-D-glycoside and stigmasterol-D-glycoside (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1. Chemical structure of the substance charantin |

| Figure 2. Qualitative reaction for determination of carbohydrates |

| Figure 3. Spectrophotometric results of M. charantia extract |

4. Conclusions

- In this study, qualitative assays for carbohydrates and steroids were conducted to identify the characteristic steroidal glycoside, charantin, in the extract of Momordica charantia fruits. The presence of steroidal glycosides was confirmed, and the detection of characteristic absorption peaks at 220 and 228 nm indicates the presence of polyphenolic compounds, particularly tannins, which was further corroborated by a qualitative reaction with lead acetate.Beyond analytical characterization, the study demonstrated that intranasal administration of liposome-encapsulated charantin produced a marked hypoglycemic effect in rats with diet-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus, reducing blood glucose levels from 7.57 mmol/L to 5.33 mmol/L within five days of treatment. These findings indicate that charantin possesses potent antidiabetic activity and that its liposomal intranasal delivery may provide an effective and non-invasive route for therapeutic application. The integration of analytical detection and biological evaluation confirms charantin as a promising natural compound for further pharmacological development in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study was supported by grant F-OT-2021-153 from the Ministry of Innovative Development of the Republic of Uzbekistan. The authors express their sincere gratitude for this support.

Abbreviations

- UV – Ultravioletnm – NanometerMAE – Microwave-Assisted ExtractionSFE – Supercritical Fluid ExtractionUE – Ultrasonic ExtractionHPLC – High-Performance Liquid ChromatographyEtOH – EthanolH₂SO₄ – Sulfuric Acid

Conflict of Interest

- The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Source

- This study was supported by grant F-OT-2021-153 from the Ministry of Innovative Development of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML