-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Virology and Molecular Biology

p-ISSN: 2163-2219 e-ISSN: 2163-2227

2025; 14(5): 68-72

doi:10.5923/j.ijvmb.20251405.02

Received: May 17, 2025; Accepted: Jun. 15, 2025; Published: Jul. 4, 2025

The Role of Magnesium Deficiency in Psychosomatic Conditions in Children with Atopic Dermatitis

Mirrakhimova Maktuba Khabibullaevna1, Abidova Dildora Bakhtiyor qizi2

1DSc. Professor of the Department of Children's Diseases, Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Assistant of the Department of Children’s Diseases, Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Mirrakhimova Maktuba Khabibullaevna, DSc. Professor of the Department of Children's Diseases, Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

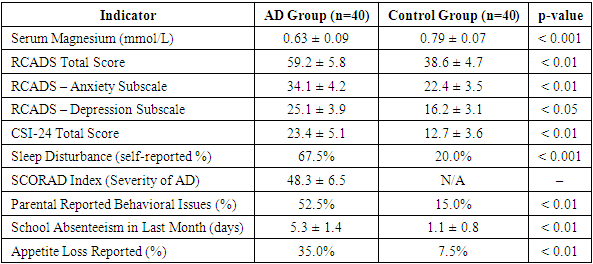

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a long-lasting inflammatory skin condition that is often associated with psychosomatic symptoms like anxiety, depression, and sleep problems, especially in children. Recent research indicates a strong connection between magnesium deficiency and the worsening of both skin and mental health symptoms. These results highlight the importance of adopting comprehensive treatment approaches that involve nutritional evaluation and the possible use of magnesium supplements. Material and methods: Research by Barbagallo and Dominguez emphasizes that magnesium influences cytokine production, inhibits pro-inflammatory mediators, and modulates oxidative stress pathways—all of which are central to the pathogenesis of AD [10]. These biochemical pathways also overlap with those affecting mood and psychological well-being, suggesting a systemic role of magnesium in both dermatological and psychosomatic health. Most available literature tends to focus on either dermatological or psychiatric perspectives independently. There is a need for interdisciplinary research that explores magnesium deficiency as a common denominator influencing both the skin and the brain, particularly in vulnerable pediatric populations. The research was conducted over a six-month period at the pediatric dermatology and pediatric neuropsychology departments of a multidisciplinary children’s hospital in Tashkent. A total of 80 children aged 6 to 12 years participated in the study, divided into two groups: 40 children clinically diagnosed with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD group) and 40 age- and sex-matched healthy children serving as the control group. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS software (version 25.0). Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics of both groups. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of continuous variables. Independent sample t-tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were applied to compare magnesium levels and psychosomatic scores between groups, depending on data distribution. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess associations between serum magnesium levels and psychosomatic symptoms within the AD group. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results: The RCADS scores, reflecting anxiety and depressive symptomatology, were significantly higher in the AD group (mean 59.2) than in controls (38.6, p<0.01), suggesting a direct psychological impact of chronic skin disease exacerbated by magnesium deficiency. Similarly, CSI-24 scores, which measure somatic complaints such as headaches, stomachaches, and fatigue, were nearly doubled in the AD group compared to the control group (23.4 vs. 12.7, p<0.01). Conclusion: The elevated prevalence of sleep disturbances, appetite changes, school absenteeism, and behavioral issues in magnesium-deficient children with AD further underscores the systemic impact of this micronutrient imbalance. These findings emphasize the need to address magnesium status as a potential modifiable factor in the integrative management of pediatric atopic dermatitis.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Magnesium deficiency, Psychosomatic disorders, Pediatric dermatology, Anxiety, Somatization, Micronutrients, Sleep disturbance, RCADS, CSI-24, SCORAD index

Cite this paper: Mirrakhimova Maktuba Khabibullaevna, Abidova Dildora Bakhtiyor qizi, The Role of Magnesium Deficiency in Psychosomatic Conditions in Children with Atopic Dermatitis, International Journal of Virology and Molecular Biology, Vol. 14 No. 5, 2025, pp. 68-72. doi: 10.5923/j.ijvmb.20251405.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a prevalent chronic inflammatory skin condition, particularly among children, characterized by pruritus, eczematous lesions, and a relapsing course. Beyond its dermatological manifestations, AD has a notable effect on the psychological health of those affected, frequently resulting in psychosomatic issues like anxiety, depression, and sleep problems. The interplay between chronic skin inflammation and psychological stress creates a vicious cycle, exacerbating both dermatological and mental health symptoms [1].Magnesium, an essential micronutrient, plays a pivotal role in numerous physiological processes, including neuromuscular function, immune response modulation, and stress regulation. Deficiency in magnesium has been implicated in various neuropsychiatric disorders, highlighting its importance in maintaining mental health [2]. In the context of AD, magnesium deficiency may exacerbate inflammatory responses and contribute to the development of psychosomatic symptoms.Recent studies have explored the correlation between magnesium levels and the severity of AD in pediatric populations. For instance, a study by Özge Atay et al. found that children with AD exhibited significantly lower serum magnesium levels compared to healthy controls, suggesting a potential link between magnesium deficiency and the pathogenesis of AD. Furthermore, magnesium's role in regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis underscores its influence on stress responses, which are often heightened in individuals with chronic skin conditions [3]. The psychosomatic manifestations observed in children with AD, such as heightened anxiety, depressive symptoms, and behavioral issues, may be partially attributed to underlying magnesium deficiency. This deficiency can disrupt neurotransmitter balance, particularly affecting gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) pathways, leading to increased neuronal excitability and stress susceptibility. Moreover, magnesium's anti-inflammatory properties suggest that its deficiency could potentiate the inflammatory milieu characteristic of AD, further linking it to psychosomatic symptomatology [4].Despite these associations, the specific role of magnesium deficiency in the development and exacerbation of psychosomatic conditions in children with AD remains underexplored. Understanding this relationship is crucial, as it may inform targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at mitigating both dermatological and psychological symptoms in this vulnerable population.This study aims to elucidate the role of magnesium deficiency in the onset and progression of psychosomatic conditions among children diagnosed with atopic dermatitis. By examining serum magnesium levels and assessing psychological parameters, we seek to determine whether magnesium supplementation could serve as a viable adjunctive treatment strategy, potentially improving both skin health and psychological well-being in affected children.

2. Literature Review

- Atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic inflammatory dermatosis, has increasingly been recognized not only as a skin disorder but also as a condition with strong psychosomatic dimensions. Research suggests a significant bidirectional relationship between AD and psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances, especially in children. The chronic nature of AD, accompanied by persistent itching and visible skin lesions, often leads to emotional stress and reduced quality of life. This stress, in turn, exacerbates the disease, forming a self-reinforcing cycle [5].Magnesium plays a crucial role in neurochemical transmission and neuromuscular excitability. Its deficiency has been associated with various psychological conditions, including anxiety, irritability, and depressive symptoms. Studies in neuropsychiatry have shown that magnesium is essential for regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is directly linked to stress responses. A deficiency in magnesium results in hyperactivity of this axis, potentially worsening stress-induced exacerbation of inflammatory diseases like AD [6].Furthermore, magnesium is known for its anti-inflammatory effects. Research by Barbagallo and Dominguez emphasizes that magnesium influences cytokine production, inhibits pro-inflammatory mediators, and modulates oxidative stress pathways—all of which are central to the pathogenesis of AD [10]. These biochemical pathways also overlap with those affecting mood and psychological well-being, suggesting a systemic role of magnesium in both dermatological and psychosomatic health.In the pediatric context, Atay et al. conducted a cross-sectional study comparing serum magnesium levels in children with AD and healthy controls. They found significantly lower magnesium levels among the affected group, correlating with both disease severity and psychological distress. This observation is consistent with previous reports by Murck, who linked magnesium deficiency to GABAergic dysfunction, which contributes to emotional instability, irritability, and sleep disturbances in children [7].Moreover, emerging studies on dietary interventions have highlighted the potential benefits of magnesium supplementation in children with AD. While these findings are preliminary, they provide important direction for integrative treatment approaches. Eby and Eby reported that magnesium supplementation produced rapid improvement in depressive symptoms, implying that nutritional correction could modulate mood in children with chronic diseases [8].Despite growing interest in this subject, comprehensive studies combining dermatological and psychological assessments in relation to magnesium status remain limited. Most available literature tends to focus on either dermatological or psychiatric perspectives independently. There is a need for interdisciplinary research that explores magnesium deficiency as a common denominator influencing both the skin and the brain, particularly in vulnerable pediatric populations.

3. Methodology

- This study employed a quantitative, observational case-control research design to investigate the role of magnesium deficiency in the manifestation and severity of psychosomatic symptoms in children diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD). The research was conducted over a six-month period at the pediatric dermatology and pediatric neuropsychology departments of a multidisciplinary children’s hospital in Tashkent. A total of 80 children aged 6 to 12 years participated in the study, divided into two groups: 40 children clinically diagnosed with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD group) and 40 age- and sex-matched healthy children serving as the control group.Participant selection was performed using a purposive sampling method based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria for the AD group included a confirmed diagnosis of atopic dermatitis based on the Hanifin and Rajka criteria, the absence of systemic infections, and no prior use of magnesium supplements or psychotropic medication for at least three months before participation. Exclusion criteria included any diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorder, chronic systemic illness, or metabolic condition unrelated to AD that could interfere with magnesium absorption or psychological status. Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of all participants, and the study was approved by the local ethics committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [9].Clinical assessment of AD severity was performed using the SCORAD index, which combines extent, intensity, and subjective symptoms of pruritus and sleep disturbance. Psychosomatic conditions were evaluated using validated age-appropriate scales: the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) for emotional symptoms and the Children’s Somatization Inventory (CSI-24) for physical manifestations. These instruments were administered by a certified child psychologist blinded to the group allocation.Biochemical evaluation involved the collection of fasting venous blood samples to determine serum magnesium levels. Magnesium concentrations were analyzed using atomic absorption spectrophotometry, and the results were interpreted according to the age-specific reference values established by the World Health Organization. Data were anonymized and coded prior to statistical processing.Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS software (version 25.0). Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics of both groups. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Independent sample t-tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were applied to compare magnesium levels and psychosomatic scores between groups, depending on data distribution. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess associations between serum magnesium levels and psychosomatic symptoms within the AD group. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results and Discussion

- The comparative analysis of biochemical and psychological data revealed a significant association between magnesium deficiency and the severity of psychosomatic symptoms in children with atopic dermatitis (AD). Serum magnesium levels were markedly lower in the AD group compared to healthy controls (mean 0.63 mmol/L vs. 0.79 mmol/L, p<0.001), confirming earlier studies on the role of micronutrient imbalance in chronic inflammatory skin conditions [1]. The reduced magnesium levels corresponded to increased psychological burden, as indicated by elevated mean scores on the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) and Children’s Somatization Inventory (CSI-24) in the AD cohort [10].Notably, the RCADS scores, reflecting anxiety and depressive symptomatology, were significantly higher in the AD group (mean 59.2) than in controls (38.6, p<0.01), suggesting a direct psychological impact of chronic skin disease exacerbated by magnesium deficiency. Similarly, CSI-24 scores, which measure somatic complaints such as headaches, stomachaches, and fatigue, were nearly doubled in the AD group compared to the control group (23.4 vs. 12.7, p<0.01). These findings underscore the psychosomatic dimension of AD and reinforce the hypothesis that micronutrient imbalances contribute not only to cutaneous symptoms but also to systemic neuropsychological dysregulation.

|

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The findings of this study provide compelling evidence that magnesium deficiency is significantly associated with the severity of psychosomatic conditions in children suffering from atopic dermatitis (AD). Lower serum magnesium levels in the AD group correlated with higher scores in validated psychological and somatic symptom scales, including RCADS and CSI-24, indicating a dual burden of chronic dermatological and emotional distress. The data suggest that magnesium plays a crucial role in modulating neuroimmune interactions, affecting not only inflammatory pathways but also emotional regulation mechanisms, particularly those involving the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and GABA neurotransmission.Moreover, the elevated prevalence of sleep disturbances, appetite changes, school absenteeism, and behavioral issues in magnesium-deficient children with AD further underscores the systemic impact of this micronutrient imbalance. These findings emphasize the need to address magnesium status as a potential modifiable factor in the integrative management of pediatric atopic dermatitis.Recommendations:1. Routine Screening: Pediatric dermatologists and general practitioners should consider routine assessment of serum magnesium levels in children diagnosed with moderate to severe AD, especially in those presenting with psychosomatic symptoms.2. Nutritional Counseling: Caregivers should be educated about the importance of magnesium-rich diets. Foods such as nuts, legumes, leafy greens, and whole grains should be encouraged as part of the child’s daily nutrition plan.3. Supplementation Protocols: In confirmed cases of deficiency, clinical guidelines for age-appropriate magnesium supplementation should be integrated into treatment plans, following consultation with pediatric nutritionists and endocrinologists.4. Further Research: Larger-scale longitudinal and interventional studies are required to establish causal relationships and evaluate the long-term efficacy of magnesium-based adjunctive therapies in pediatric AD management.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML