-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical Physics

p-ISSN: 2167-6844 e-ISSN: 2167-6852

2021; 11(6): 159-161

doi:10.5923/j.ijtmp.20211106.01

Received: Dec. 1, 2021; Accepted: Dec. 17, 2021; Published: Dec. 24, 2021

The Transformation of Spacetime Coördinates between Inertial Frames

Thomas Erber1, 2, 3, 4, Porter W. Johnson1, 3

1Department of Physics, IIT, Chicago IL, USA

2Department of Applied Mathematics, IIT, Chicago IL, USA

3Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago IL, USA

4Department of Physics, University of Chicago, Chicago IL, USA

Correspondence to: Porter W. Johnson, Department of Physics, IIT, Chicago IL, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

We make only the following two requirements: (1) inertial invariance and (2) that the product of two boosts in a given direction yields a boost in the same direction. It is shown that there are three (consistent) possibilities: (a) a Galilean transform, (b) a Lorentz transform, or (c) a rotation in Euclidean spacetime. For the case of the Lorentz transform, the relativistic rule for composition of velocities is obtained, with the velocity of light arising as a constant of integration.

Keywords: Lorentz Transformation, Gallilei Transformation, Special Relativity

Cite this paper: Thomas Erber, Porter W. Johnson, The Transformation of Spacetime Coördinates between Inertial Frames, International Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical Physics, Vol. 11 No. 6, 2021, pp. 159-161. doi: 10.5923/j.ijtmp.20211106.01.

1. Introduction

- Physics in the twentieth century may be characterized by an understanding of the rôle played by the symmetries of physical system. Although the subject became prominent in the 1920s through the work of Hermann Weyl in the subject of quantum mechanics, an important precursor of group theory in physics was proposed in 1911, in the study of the group properties of space-time transformations by Phillip Frank and Hermann Rothe.1 They showed the unique rôle of the Galilei and Lorentz transformations in this topic, inasmuch as only these transformations in two dimensional space-time

were consistent with the group transformation property. Unfortunately, although that approach could have led to highlighting the rôle of symmetry groups in all physical systems, it did not happen that way. We have reconsidered the matter studied by Frank and Rothe in this work, requiring that the composition of two boosts in space-time be a boost of similar character. We find three possibilities, corresponding to a Galilei transformation, a Lorentz transformation, and a rotation in a Euclidean space-time. In addition we find in Section II that a space-time dilation may be present in each of these three cases, but a physical reason for eliminating the dilatations is described. The issues are discussed in Section III. The Euclidean rotation occurs as mathematical possibility, but it can be rejected upon physical grounds, as we discuss. While the symmetries imposed by group compositions provide an important limitation upon physical systems, they must be supplemented by physical requirements, in this and many other cases.

were consistent with the group transformation property. Unfortunately, although that approach could have led to highlighting the rôle of symmetry groups in all physical systems, it did not happen that way. We have reconsidered the matter studied by Frank and Rothe in this work, requiring that the composition of two boosts in space-time be a boost of similar character. We find three possibilities, corresponding to a Galilei transformation, a Lorentz transformation, and a rotation in a Euclidean space-time. In addition we find in Section II that a space-time dilation may be present in each of these three cases, but a physical reason for eliminating the dilatations is described. The issues are discussed in Section III. The Euclidean rotation occurs as mathematical possibility, but it can be rejected upon physical grounds, as we discuss. While the symmetries imposed by group compositions provide an important limitation upon physical systems, they must be supplemented by physical requirements, in this and many other cases.2. Analysis

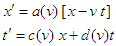

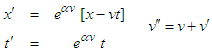

- The most general linear transformation of spacetime coördinates

into

into  that transforms the origin

that transforms the origin  into itself is

into itself is The parameters

The parameters  depend only on the velocity

depend only on the velocity  of the two frames, which we introduce by requiring that the points

of the two frames, which we introduce by requiring that the points  lie along the line

lie along the line  , so that

, so that | (1) |

correspond to the line

correspond to the line  , so that

, so that and

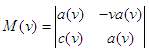

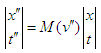

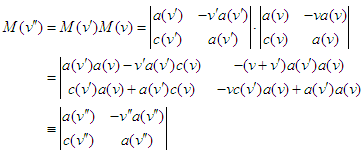

and  . Let us write these equations in matrix form:

. Let us write these equations in matrix form: | (2) |

| (3) |

and

and  is given by

is given by where

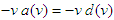

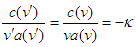

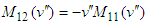

where From the requirement that the diagonal elements of

From the requirement that the diagonal elements of  are equal we obtain

are equal we obtain  , so that

, so that | (4) |

is a constant independent of

is a constant independent of  or

or  . Thus

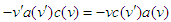

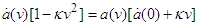

. Thus  . Furthermore, from the requirement

. Furthermore, from the requirement  we obtain

we obtain | (5) |

| (6) |

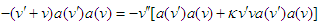

leads to the nonlinear functional equation

leads to the nonlinear functional equation | (7) |

, then

, then  and

and  , or

, or  . Let us differentiate Eq. (7) with respect to

. Let us differentiate Eq. (7) with respect to  and then set

and then set  to obtain

to obtain | (8) |

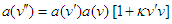

, with the parameter

, with the parameter  present. We may write it as

present. We may write it as | (9) |

may be positive, zero, or negative.For the simplest case

may be positive, zero, or negative.For the simplest case  we obtain the solution

we obtain the solution  , or

, or | (10) |

we obtain the Galilei transformation, whereas the parameter

we obtain the Galilei transformation, whereas the parameter  also introduces a space-time dilation or contraction.For positive

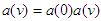

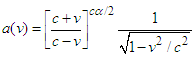

also introduces a space-time dilation or contraction.For positive  we write

we write  . where

. where  is the characteristic velocity. The solution to Eq. (9) is

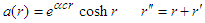

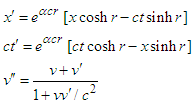

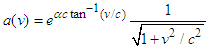

is the characteristic velocity. The solution to Eq. (9) is We may express these relations more elegantly in terms of the 'rapidity' parameter

We may express these relations more elegantly in terms of the 'rapidity' parameter  , with

, with  :

: Equivalently

Equivalently | (11) |

produces a scale transformation, as before. With

produces a scale transformation, as before. With  we obtain the Lorentz boost with velocity

we obtain the Lorentz boost with velocity  .Finally, for negative

.Finally, for negative  we write

we write  . where

. where  is the velocity scale. The solution is

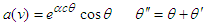

is the velocity scale. The solution is The solution to Eq. (9) is conveniently expressed in terms of the angle

The solution to Eq. (9) is conveniently expressed in terms of the angle  , with

, with  :

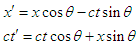

: Equivalently

Equivalently | (12) |

this corresponds to a rotation by angle

this corresponds to a rotation by angle  in the Euclidean

in the Euclidean  plane. Again, the parameter

plane. Again, the parameter  induces a scale transformation.

induces a scale transformation.3. Discussion

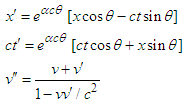

- First we consider the Galilei transformation, Eq. (9), that was obtained in the previous section. For the three dimensional case this can be generalized to obtain

| (13) |

. Upon this basis, we must make the replacement

. Upon this basis, we must make the replacement  to recover the pure Galilei transform. These transforms yield an Abelian group.For the case of the Euclidean rotation in space-time, we should similarly eliminate the scale factor

to recover the pure Galilei transform. These transforms yield an Abelian group.For the case of the Euclidean rotation in space-time, we should similarly eliminate the scale factor  by setting

by setting  , to obtain the pure space-time rotation

, to obtain the pure space-time rotation | (14) |

.Although for this case a characteristic velocity

.Although for this case a characteristic velocity  arises, there is no limit upon the velocity

arises, there is no limit upon the velocity  . In fact, the rule for composition of velocities, Eq. (12), permits arbitrarily large velocities. Furthermore, the composition of two positive velocities

. In fact, the rule for composition of velocities, Eq. (12), permits arbitrarily large velocities. Furthermore, the composition of two positive velocities  and

and  is negative, provided that

is negative, provided that  . This bizarre circumstance requires rejection of this transformation as a physical possibility. In the Euclidean transformation, the characteristic velocity would not be inertially invariant, in contradiction to the inference of the Michelson-Morley experiment. In fact, it would yield a length dilation and time contraction, in contradiction with experiment. By similar reasoning, one must set

. This bizarre circumstance requires rejection of this transformation as a physical possibility. In the Euclidean transformation, the characteristic velocity would not be inertially invariant, in contradiction to the inference of the Michelson-Morley experiment. In fact, it would yield a length dilation and time contraction, in contradiction with experiment. By similar reasoning, one must set  , or the scale factor

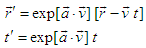

, or the scale factor  in Eq.(11) to obtain the Lorentz transformation. As promised, the inertial invariance of the characteritic velocity arises as a consequence of the group composition property for this case. For consistency with Maxwell's equations, that velocity must be interpreted as the velocity of light.Note that the Lorentz transformations in three spatial dimensions do not form a group, since the product of two transformations with respective velocities

in Eq.(11) to obtain the Lorentz transformation. As promised, the inertial invariance of the characteritic velocity arises as a consequence of the group composition property for this case. For consistency with Maxwell's equations, that velocity must be interpreted as the velocity of light.Note that the Lorentz transformations in three spatial dimensions do not form a group, since the product of two transformations with respective velocities  and

and  with

with  does not yield a Lorentz transformation, but in addition a spatial rotation in the plane perpendicular to

does not yield a Lorentz transformation, but in addition a spatial rotation in the plane perpendicular to  and

and  is needed. The full Lorentz group coonsists of spatial rotations and Lorentz boosts, the rotations forming a subgroup.

is needed. The full Lorentz group coonsists of spatial rotations and Lorentz boosts, the rotations forming a subgroup.Note

- 1. Über die Transformation der Raumzeitkoordinationen von ruhenden auf bewegte Systeme, Annalen der Physics, 3, 325-355, 1911. Our English translation of this article appears in this journal, 11, 141-152 (2021).

Abstract

Abstract Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML