-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical Physics

p-ISSN: 2167-6844 e-ISSN: 2167-6852

2020; 10(6): 113-119

doi:10.5923/j.ijtmp.20201006.01

Received: Nov. 19, 2020; Accepted: Nov. 30, 2020; Published: Dec. 5, 2020

A Hollow Spherical Gaseous Shell Approaching Horizon

Doron Kwiat

Israel

Correspondence to: Doron Kwiat, Israel.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The definition of horizon in gravitation is based on the GM factor. This factor defines the Schwarzschild radius and hence the radius of the horizon. Evidently, this factor depends on density and radius alone. There is no direct connection to curvature. In a solid sphere one may change mass by either density or radius. If mass and density are fixed, radius must be fixed. It is shown here that for a hollow shell, mass and density may be fixed, while radii change. By change of shell's thickness and radius, one may transform a shell to a black hole while keeping mass and density fixed. Thus, the transition through horizon and formation of a black hole may be the result of curvature change alone, without an increase of neither mass nor density. It is also shown how a black hole can be created from a free fall collapse of a shell's outer and inner edges, while mass and density are kept fixed. For a non-rotating, neutral dust, of non-interacting particles and with no internal radiation processes, the internal pressure of a hollow sphere is investigated. The minimal value of pressure needed to hold against collapse is considered.

Keywords: Shell, Sphere, Schwarzschild radius, Gaseous hollow shell, Pressure

Cite this paper: Doron Kwiat, A Hollow Spherical Gaseous Shell Approaching Horizon, International Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical Physics, Vol. 10 No. 6, 2020, pp. 113-119. doi: 10.5923/j.ijtmp.20201006.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

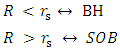

- Is it possible to take a black hole and turn it to a standard object?The answer is of course that one can do it by either removing parts of its mass (reducing M), or, by increasing its volume, so that its density is reduced.Black holes are assumed to be of spherical shapes. Either symmetric with J=0, or non-symmetric with J≠0. They may be charged or neutral [1-5]. Hollow spherical shells have also been discussed [7-16]. Hollow cylindrical dust shells, with pressure conditions of Einstein-Bose gas have been discussed recently [21-25]. Here we examine the internal pressure under various gas pressure-volume parameters.In all cases, one assumes that changes of an object from a standard object (SOB), to a black hole (BH), requires an increase in mass or density or both, enough to make its radius R smaller than its Schwarzschild radius

In this work, we will show that a hollow shell of finite size and thickness can collapse into a black hole, while keeping a fixed density and fixed mass. This, in contrast to the assumption that a black hole is a result of a given object, collapsing under gravitational forces, due to an enormous increase in density or mass, while reducing its radius R. (here R is its radius in case of a symmetrical sphere, or max(R1, R2, R3) in case of an asymmetrical rotating ellipsoid with radii R1, R2 and R3).It will also be shown, that during free fall of the two edges of a shell under central gravitational force, the shell will retain its density and mass while shrinking below the Schwarzschild radius, transforming to a black hole. This black hole cannot be discerned from a spherical black hole by a remote observer. One must conclude that the reason for black holes is not their mass nor their densities. Rather, it is the amount of curvature of spacetime alone, that determines the transition.It is also shown that during free fall of non-relativistic particles of a dust shell, the shell's thickness will preserve the required conditions for a fixed density. Hence, the transition to a black hole will depend on the radii alone while mass and density are kept fixed.

In this work, we will show that a hollow shell of finite size and thickness can collapse into a black hole, while keeping a fixed density and fixed mass. This, in contrast to the assumption that a black hole is a result of a given object, collapsing under gravitational forces, due to an enormous increase in density or mass, while reducing its radius R. (here R is its radius in case of a symmetrical sphere, or max(R1, R2, R3) in case of an asymmetrical rotating ellipsoid with radii R1, R2 and R3).It will also be shown, that during free fall of the two edges of a shell under central gravitational force, the shell will retain its density and mass while shrinking below the Schwarzschild radius, transforming to a black hole. This black hole cannot be discerned from a spherical black hole by a remote observer. One must conclude that the reason for black holes is not their mass nor their densities. Rather, it is the amount of curvature of spacetime alone, that determines the transition.It is also shown that during free fall of non-relativistic particles of a dust shell, the shell's thickness will preserve the required conditions for a fixed density. Hence, the transition to a black hole will depend on the radii alone while mass and density are kept fixed.2. Comparing a Full Sphere to a Hollow Spherical Shell

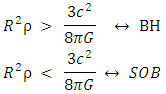

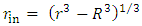

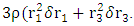

- Consider a full sphere of radius R and mass M and density ρ, and compare it to a hollow spherical shell of same mass M and density ρ, with outer and inner radii,

and

and  , respectively.For all objects the Schwartzschild radius is defined by

, respectively.For all objects the Schwartzschild radius is defined by  The criteria for transition from a BH to SOB is whether the objects radius R is greater or smaller than

The criteria for transition from a BH to SOB is whether the objects radius R is greater or smaller than

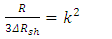

Since the relation between mass M and raius R are determined by the volume and density, this may be reformulated as

Since the relation between mass M and raius R are determined by the volume and density, this may be reformulated as This shows that there are two ways to create a BH:1. Keep R fixed and increase ρ.2. Keep ρ fixed and increase R.For a full sphere, one cannot keep both the mass M and the density ρ fixed constant, and convert

This shows that there are two ways to create a BH:1. Keep R fixed and increase ρ.2. Keep ρ fixed and increase R.For a full sphere, one cannot keep both the mass M and the density ρ fixed constant, and convert

| Figure 1. Changing outer and inner radii of a hollow shell in comparison to a full spherical object of radius R, while keeping both object's masses and densities equal and fixed |

and

and  and comparing it to a full sphere of radius R, both having the same mass M and same density ρ, one can keep the mass

and comparing it to a full sphere of radius R, both having the same mass M and same density ρ, one can keep the mass  and density ρ fixed, and yet allow the hollow shell to undergo the transformation

and density ρ fixed, and yet allow the hollow shell to undergo the transformation  This transformation can be achieved by changing both

This transformation can be achieved by changing both  and

and  according to:

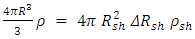

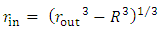

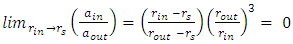

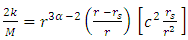

according to: | (1) |

3. Transforming a Standard Spherical Shell into a Black Hole into

- Consider a non-rotating spherically symmetric stellar object of mass M, of radius R, of density

, and with a Schwarzschild radius

, and with a Schwarzschild radius  We know that whenever

We know that whenever  it is considered a black hole, and when

it is considered a black hole, and when  it is considered a standard stellar object.Suppose we take this object and transform its mass into a very thin spherical shell of radius

it is considered a standard stellar object.Suppose we take this object and transform its mass into a very thin spherical shell of radius  , and of width

, and of width  . We also denote its new density by

. We also denote its new density by  .By comparing the two objects, before and after the transformation:

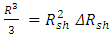

.By comparing the two objects, before and after the transformation: | (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

and

and  respectively.Comparing the shell's mass to the sphere's mass M

respectively.Comparing the shell's mass to the sphere's mass M | (5) |

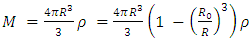

, namely an infinitesimally thin shell of radius R.For the most general case, where a sphere of radius R is transformed into a shell of internal and external radii

, namely an infinitesimally thin shell of radius R.For the most general case, where a sphere of radius R is transformed into a shell of internal and external radii  and

and  respectively, one obtains (keeping the densities of both objects fixed):

respectively, one obtains (keeping the densities of both objects fixed): | (6) |

| (7) |

gives condition for the shell, with relation to the Schwarzschild radius:

gives condition for the shell, with relation to the Schwarzschild radius: | (8) |

(the object has just become a black hole, the outer radius of the shell will be

(the object has just become a black hole, the outer radius of the shell will be  . The larger the radius R, the thinner the shell.Notice, that so far there has been no assumption made about the nature of the matter involved. It is so far true for dust like gas as well as for charged, high density, high pressure object. Though, no energy may escape in form of radiation processes. For a thin enough shell, one can expand it indefinitely and keep the characteristics of the original object:1. The mass M of the shell is kept, hence the Schwarzschild radius

. The larger the radius R, the thinner the shell.Notice, that so far there has been no assumption made about the nature of the matter involved. It is so far true for dust like gas as well as for charged, high density, high pressure object. Though, no energy may escape in form of radiation processes. For a thin enough shell, one can expand it indefinitely and keep the characteristics of the original object:1. The mass M of the shell is kept, hence the Schwarzschild radius  remains the same.2. From a far enough distance, both the original sphere and the expanded shell will have the same gravitational attraction.3. The density is kept the same for both objects, thus one cannot attribute the Black hole to an indefinite increase in density.If for the original sphere, the Schwarzschild radius

remains the same.2. From a far enough distance, both the original sphere and the expanded shell will have the same gravitational attraction.3. The density is kept the same for both objects, thus one cannot attribute the Black hole to an indefinite increase in density.If for the original sphere, the Schwarzschild radius  was outside R, for the shell, one can pick its thickness to be small enough, so that its radius

was outside R, for the shell, one can pick its thickness to be small enough, so that its radius  is much larger than

is much larger than  thus making the shell into a standard (non-black hole) object.

thus making the shell into a standard (non-black hole) object.4. Free Fall

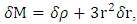

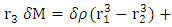

- Consider now particles at the outer and inner edges of the shell. Assume two particles, at very large distances

and

and  from a common attracting center point undergo free fall. They fall at accelerations

from a common attracting center point undergo free fall. They fall at accelerations  and

and  respectively. These free fall accelerations can be easily shown to have the relation

respectively. These free fall accelerations can be easily shown to have the relation | (9) |

and therefore

and therefore | (10) |

| (11) |

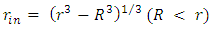

| (12) |

with r and

with r and  with

with  to obtain

to obtain | (13) |

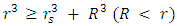

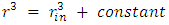

is valid for a shell undergoing free fall towards a common attracting center of a central gravitational field.Therefore, the model of a free-falling shell answers the requirement of having the density fixed.At least for a collision free gas of non-interacting, free falling particles, the shell model will (under a weak-field assumption) contract towards a common center and can eventually become a black hole. We notice that at both its external edges, the shell's gas is in contact with free space and therefore the edges are at zero temperature. The assumption on collision less gas particles is valid.This model is different from the model of gravitational collapse due to increased density or increased mass,The shell model represents gravitational collapse under constant density, constant mass and constant Schwarzschild radius

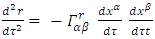

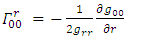

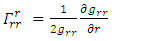

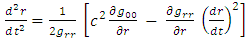

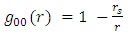

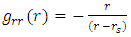

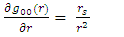

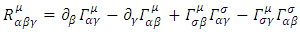

is valid for a shell undergoing free fall towards a common attracting center of a central gravitational field.Therefore, the model of a free-falling shell answers the requirement of having the density fixed.At least for a collision free gas of non-interacting, free falling particles, the shell model will (under a weak-field assumption) contract towards a common center and can eventually become a black hole. We notice that at both its external edges, the shell's gas is in contact with free space and therefore the edges are at zero temperature. The assumption on collision less gas particles is valid.This model is different from the model of gravitational collapse due to increased density or increased mass,The shell model represents gravitational collapse under constant density, constant mass and constant Schwarzschild radius  The model is limited to free falling particles under dilute, non-rotating, neutral gas conditions and so modifications will be required to include internal interactions due to pressure, charge and nuclear processes.In the general relativistic case, a falling particle path is determined by

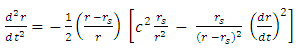

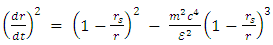

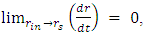

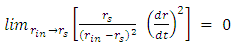

The model is limited to free falling particles under dilute, non-rotating, neutral gas conditions and so modifications will be required to include internal interactions due to pressure, charge and nuclear processes.In the general relativistic case, a falling particle path is determined by | (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

with

with  and

and  with

with  to obtain:

to obtain: | (23) |

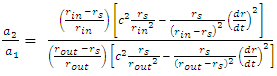

and

and  are the outer and inner radii of the shell, respectively.Case 1:

are the outer and inner radii of the shell, respectively.Case 1:

| (24) |

| (25) |

Implies, as before,

Implies, as before,  Therefore, for a non-relativistic case, at far distance, the collapsing (under free fall) hollow shell retains a constant volume andthe mass and density are kept similar to a full spherical object of radius R and of same density and mass.Case 2:

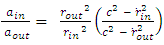

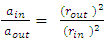

Therefore, for a non-relativistic case, at far distance, the collapsing (under free fall) hollow shell retains a constant volume andthe mass and density are kept similar to a full spherical object of radius R and of same density and mass.Case 2:  From energy considerations for a free-falling particle of mass

From energy considerations for a free-falling particle of mass  and energy

and energy  :

: | (26) |

and also

and also | (27) |

| (28) |

5. Internal Pressure

- We will consider a simplified model of gaseous material of non-interacting particles, uncharged, with zero angular momentum and with no thermonuclear sources.In the non-relativistic case

this means that the shell's internal volume is constant in time. Assuming the shell is isolated from external radiation, and if no internal nuclear processes take place, the pressure must be constant too. Otherwise, radiation from the inside will flow out, or radiation from the outside will flow into the shell.But, when approaching the horizon, the inner skin acceleration

this means that the shell's internal volume is constant in time. Assuming the shell is isolated from external radiation, and if no internal nuclear processes take place, the pressure must be constant too. Otherwise, radiation from the inside will flow out, or radiation from the outside will flow into the shell.But, when approaching the horizon, the inner skin acceleration  and its speed

and its speed  reduces to zero. On this ocasion, there is no limitation yet on the outer shell's skin and so it continues in its approach towards center. This means that the shell's volume must be reduced at the cost of increased internal pressure inside the shell.Once the internal pressure becomes high enough, the outer skin of the shell will not be able to continue its propagation and the shell will become stable, with fixed radii. This may be a function of the approach rate and it may result in fluctuations of the outer skin, and stability will not be reached until energy dissipation processes will act to reduce fluctuations. But this is a subject for evolved thermodynamics and quantum considerations [17,18].Assume the inner skin has reached a near stop at horizon

reduces to zero. On this ocasion, there is no limitation yet on the outer shell's skin and so it continues in its approach towards center. This means that the shell's volume must be reduced at the cost of increased internal pressure inside the shell.Once the internal pressure becomes high enough, the outer skin of the shell will not be able to continue its propagation and the shell will become stable, with fixed radii. This may be a function of the approach rate and it may result in fluctuations of the outer skin, and stability will not be reached until energy dissipation processes will act to reduce fluctuations. But this is a subject for evolved thermodynamics and quantum considerations [17,18].Assume the inner skin has reached a near stop at horizon  and the outer skin

and the outer skin  is moving still towards center. The internal pressure

is moving still towards center. The internal pressure  increases while the volume decreases. We will assume an adiabatic change so that the internal temperature remains constant.For a stellar gas [19,20] the relation between pressure and temperature is given by

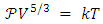

increases while the volume decreases. We will assume an adiabatic change so that the internal temperature remains constant.For a stellar gas [19,20] the relation between pressure and temperature is given by | (29) |

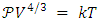

for an ideal gas.At relatively low densities, the pressure of a fully degenerate gas can be derived by treating the system as an ideal Fermi gas, in this way

for an ideal gas.At relatively low densities, the pressure of a fully degenerate gas can be derived by treating the system as an ideal Fermi gas, in this way | (30) |

| (31) |

with

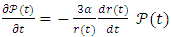

with  between 1 and 1.66 according to the gaseous state.The change in internal pressure is given by

between 1 and 1.66 according to the gaseous state.The change in internal pressure is given by | (32) |

and

and  the solution is

the solution is | (33) |

| (34) |

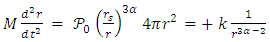

The acceleration of the outer skin, towards the horizon under the internal pressure, falls off in proportion to

The acceleration of the outer skin, towards the horizon under the internal pressure, falls off in proportion to  instead of

instead of  under free fall (Eq. 21).Gravitation causes acceleration towards center while pressure accelerates outward away from center, so that the total acceleration is given by

under free fall (Eq. 21).Gravitation causes acceleration towards center while pressure accelerates outward away from center, so that the total acceleration is given by | (35) |

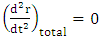

, the internal pressure is high enough to prevent collapse.Equilibrium occurs when

, the internal pressure is high enough to prevent collapse.Equilibrium occurs when  . Since we are investigating the situation near horizon, one may neglect the velocity

. Since we are investigating the situation near horizon, one may neglect the velocity  and hence

and hence | (36) |

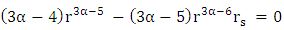

is independent of r, and so by derivation with respect to r one obtains:

is independent of r, and so by derivation with respect to r one obtains: Thus, the solution of Eq. 36 is:

Thus, the solution of Eq. 36 is: | (37) |

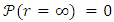

and so

and so  , and as

, and as

At very high densities, most particles are forced into quantum states with relativistic energies.

At very high densities, most particles are forced into quantum states with relativistic energies.  . However, the solution of Eq 36 is dealing with non-relativistic speeds. At relatively low densities, for an ideal Fermi gas

. However, the solution of Eq 36 is dealing with non-relativistic speeds. At relatively low densities, for an ideal Fermi gas  , and equilibrium will occur at

, and equilibrium will occur at  which is at complete collapse inside the horizon.Letting

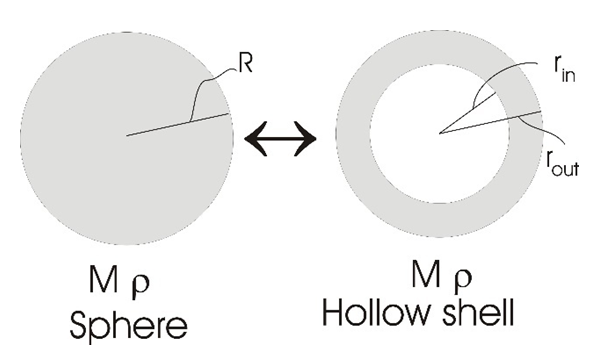

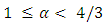

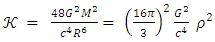

which is at complete collapse inside the horizon.Letting  be a variable representing the various gaseous states (from an ideaal gas, to compressed gas), it may vary in the range

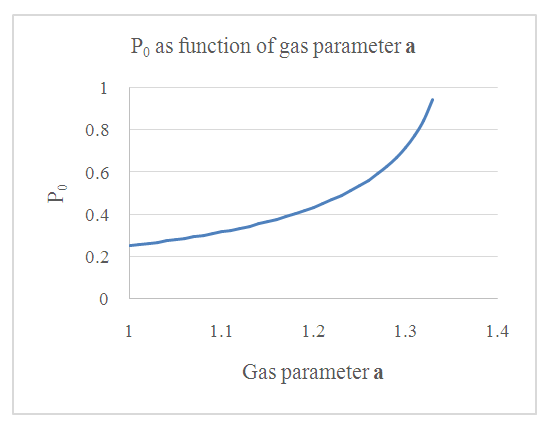

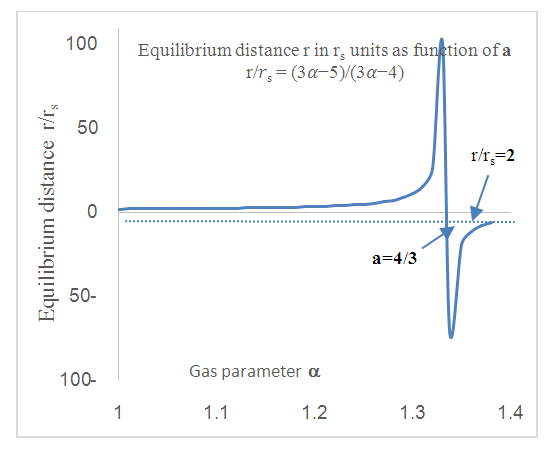

be a variable representing the various gaseous states (from an ideaal gas, to compressed gas), it may vary in the range  . The following graph depicts the variation of the equilibrium distance r, (in units of

. The following graph depicts the variation of the equilibrium distance r, (in units of  ).Obviously, only values in the range 1 to < 4/3 are valid in this model, since higher values will give

).Obviously, only values in the range 1 to < 4/3 are valid in this model, since higher values will give  and this is below the horizon.

and this is below the horizon. ?

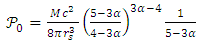

? | (38) |

is depicted as function of

is depicted as function of

| Figure 3. The internal pressure at equilibrium depends on the mass M, the Schwarzschild the gas characteristic volume dependent constant a. This is described by in this figure by  |

6. Curvature

- There is a topological difference between a solid 3D sphere and a hollow 3D shell.A solid symmetrical sphere is characterized by a single radius r while a solid symmetrical hollow shell is characterized by two radii

and

and  If asymmetrical solid sphere is considered, then it is characterized by 3 raddii

If asymmetrical solid sphere is considered, then it is characterized by 3 raddii  and

and  , whereas an asymmetrical shell requires 6 radii to describe it

, whereas an asymmetrical shell requires 6 radii to describe it  and

and  for the inner skin and

for the inner skin and  and

and  for the outer skin.If we take a solid sphere of mass M, and try to change its density and radius while keeping the mass fixed, we see from

for the outer skin.If we take a solid sphere of mass M, and try to change its density and radius while keeping the mass fixed, we see from | (39) |

and

and

| (40) |

and

and  , while changing two of the radii

, while changing two of the radii  and

and  There must be at least 2 degrees of freedom (two radii) to do this, and in a hollow shell we do have. Contrary to a solid spher, where there is only one degree of freedom (a single radius).By definition, the horizon is given by the Schwarzschild radius

There must be at least 2 degrees of freedom (two radii) to do this, and in a hollow shell we do have. Contrary to a solid spher, where there is only one degree of freedom (a single radius).By definition, the horizon is given by the Schwarzschild radius  The criterion for the horizon is the mass M, or, density together with radius. If M is fixed, so are the radius and density. One cannot change the Schwarzschild radius by changing density alone nor radius alone. The two must change simultaneously.However, in the case of a hollow shel of a fixed mass M, one may change the Schwarzschild radius without changing the density, and yet change of radii.A solid sphere of given fixed mass and density will have a fixed Schwarzschild radius and a fixed radius.A hollow shell of given fixed mass and density will have a flexible Schwarzschild radius and flexible radii.In other words, we have a new criterion for turning a spherical shell into a black hole. Rather than its mass M or density, its radii determine its Schwarzschild radius.Take a shell of given radius and thickness. Increase its thickness while reducing its radius, and it will turn into a black (hollow shell) hole. Reduce its thickness while increasing its radius and it will become of radius larger than

The criterion for the horizon is the mass M, or, density together with radius. If M is fixed, so are the radius and density. One cannot change the Schwarzschild radius by changing density alone nor radius alone. The two must change simultaneously.However, in the case of a hollow shel of a fixed mass M, one may change the Schwarzschild radius without changing the density, and yet change of radii.A solid sphere of given fixed mass and density will have a fixed Schwarzschild radius and a fixed radius.A hollow shell of given fixed mass and density will have a flexible Schwarzschild radius and flexible radii.In other words, we have a new criterion for turning a spherical shell into a black hole. Rather than its mass M or density, its radii determine its Schwarzschild radius.Take a shell of given radius and thickness. Increase its thickness while reducing its radius, and it will turn into a black (hollow shell) hole. Reduce its thickness while increasing its radius and it will become of radius larger than  and thus stop being a black hole.We see, that the nature of the object, being a black hole or a standard, is determined by the thickness of the shell and of its radius. One may keep the density and mass fixed, while increasing the shell's radius and reducing its thickness.It is therefore the curvature

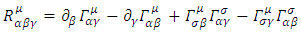

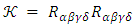

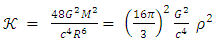

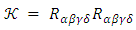

and thus stop being a black hole.We see, that the nature of the object, being a black hole or a standard, is determined by the thickness of the shell and of its radius. One may keep the density and mass fixed, while increasing the shell's radius and reducing its thickness.It is therefore the curvature  | (41) |

| (42) |

with

with  and

and  the inner curvature becomes infinite. Yet the shell is not a black hole.It must therefore be the curvature of the outer skin that will determine the criterion for turning a hollow shell into a black hole.For a Schwarzschild black hole of mass M and radius R6:

the inner curvature becomes infinite. Yet the shell is not a black hole.It must therefore be the curvature of the outer skin that will determine the criterion for turning a hollow shell into a black hole.For a Schwarzschild black hole of mass M and radius R6: | (43) |

and decreases with R.Same equation will be true for a hollow shel, only where R is the external radius.We see, that the nature of the object, being a black hole or a standard, is determined by the thickness of the shell and of its radius. One may keep the density and mass fixed, while increasing the shell's radius and reducing its thickness.In contrast to a solid sphere, where

and decreases with R.Same equation will be true for a hollow shel, only where R is the external radius.We see, that the nature of the object, being a black hole or a standard, is determined by the thickness of the shell and of its radius. One may keep the density and mass fixed, while increasing the shell's radius and reducing its thickness.In contrast to a solid sphere, where  in a hollow shell, of radii

in a hollow shell, of radii  and

and

Therefore, one may have

Therefore, one may have  and

and  while changing two of the radii

while changing two of the radii  and

and  The criterion for the horizon is no longer the mass alone (as required by the Schwarzschild radius

The criterion for the horizon is no longer the mass alone (as required by the Schwarzschild radius  .In a hollow shell, one may change the Schwarzschild radius by changes in radii alone while keeping mass M and density

.In a hollow shell, one may change the Schwarzschild radius by changes in radii alone while keeping mass M and density  fixed.In other words, we have a new criterion for turning a spherical shell into a black hole. Rather than its mass M or density, it is its curvature.Take a shell of given radius and thickness. Increase its thickness while reducing its radius, and it will turn into a black spherical shell hole. Reduce its thickness while increasing its radius and it will become of radius larger than

fixed.In other words, we have a new criterion for turning a spherical shell into a black hole. Rather than its mass M or density, it is its curvature.Take a shell of given radius and thickness. Increase its thickness while reducing its radius, and it will turn into a black spherical shell hole. Reduce its thickness while increasing its radius and it will become of radius larger than  and thus stop being a black hole.It is therefore the curvature

and thus stop being a black hole.It is therefore the curvature  | (44) |

| (45) |

| (46) |

and decreases with R.

and decreases with R.7. Conclusions

- For a dilute non-rotating uncharged dust like gas, a spherically symmetric object may change its character from being a black hole to standard and vice versa independently of its mass and density.According to the above argumentation, one may transform the sphere into a shell and accordingly find a shell with the right size so it changes the nature of the object.By changing the external and internal radii of a shell, its mass and density can be kept fixed, and yet transform from a standard object to become a black hole, and vice a versa, transform from being a black hole shell to become a standard shell. All this without changing the mass and the density.Under adiabatic collapse, the internal pressure of the shell falss off as

, while the outer skin approaches horizon with acceleration decreasing as

, while the outer skin approaches horizon with acceleration decreasing as  .The transformation is the result of change in curvature alone and does not depend on the object's mass or density.

.The transformation is the result of change in curvature alone and does not depend on the object's mass or density. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML

This is described by in this figure by r/𝑟s = (3𝛼−5)/(3𝛼−4)

This is described by in this figure by r/𝑟s = (3𝛼−5)/(3𝛼−4)