-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical Physics

p-ISSN: 2167-6844 e-ISSN: 2167-6852

2012; 2(6): 170-186

doi: 10.5923/j.ijtmp.20120206.02

On Stability of Curvilinear Shock Wave in a Viscous Gas

Alexander Blokhin 1, Boris Semisalov 2

1Sobolev Institute of Mathematics SB RAS, 4 Acad. Koptyug avenue, 630090, Novosibirsk Russia

2Design Technological Institute of Digital Techniques SB RAS, 6 Akad. Rzhanov street, 630090, Novosibirsk Russia

Correspondence to: Boris Semisalov , Design Technological Institute of Digital Techniques SB RAS, 6 Akad. Rzhanov street, 630090, Novosibirsk Russia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The planar shock wave in a viscous gas which is treated as a strong discontinuity is unstable against small perturbations. As in the case of a planar shock wave we suggest such boundary conditions that the linear initial-boundary value problem on the stability of a curvilinear shock wave (subject to these boundary conditions) is well-posed. We also propose a new effective computational algorithm for investigation the stability. This algorithm uses the nonstationary regularization, the method of lines, the stabilization method, the spline function technique and the sweep method. Applying it we succeed to obtain the stationary solution of the considered boundary-value problem justifying the stability of shock wave.

Keywords: Stability of Shock Wave, Compressible Heat-Conducting Polytropic Viscous Gas, Navier-Stokes Equations, Rankine-Hugoniot Conditions, Linearization of Function, Numerical Solutions, Stabilization Method, Regularization

Cite this paper: Alexander Blokhin , Boris Semisalov , "On Stability of Curvilinear Shock Wave in a Viscous Gas", International Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical Physics, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 170-186. doi: 10.5923/j.ijtmp.20120206.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The motion of continuous media is often accompanied by the formation of transitional zones of strong gradients, where flow parameters (velocity, density, pressure, temperature, etc.) vary rapidly. If dissipative mechanisms are neglected, then such thin zones are usually treated as surfaces of strong discontinuity. In that case the flow parameters change step-wise with jumps on a propagating surface of strong discontinuity (e.g., shock wave). Note that motions of ideal continuous media are usually described by hyperbolic conservation laws for which the mathematical theory of shock waves has been well discovered not only for one-dimensional[1–10] but also for multi-dimensional flows[11–21].Concerning continuous media with dissipation (e.g., viscosity, heat conduction, etc.), transitional zones of strong gradients can also be formed, and there emerges the necessity for the mathematical modeling of such a phenomenon. In this paper, we are concerned with the motion of a viscous compressible gas in the framework of the Navier-Stokes model. As is known, the Navier-Stokes equations are applied for solving the problem on shock structure in a viscous and heat conducting gas (see, e.g., the classical approach in[22]). In this problem, instead of a surface of strong discontinuity one considers a thin transitional zone (viscous profile) where flow parameters vary continuously.A strong discontinuity in an ideal medium is said to have a viscous profile (or structure) if the discontinuous flow is a limiting one under vanishing dissipation[22–25]. Although, it should be noted that until now such a viscous profile (continuous) approach was applying for different concrete models of continuum mechanics mainly in the one-dimensional case. So, it cannot be fully considered as an alternative one to the discontinuous approach for multi-dimensional shock fronts. At the same time, for continuous media with dissipation only the continuous approach has yet a sufficient justification (at least, on the one-dimensional level[26]).The indirect confirmation of the correctness of precisely this continuous approach for viscous conservation laws is the following. Hyperbolic conservation laws modeling motions of ideal media have such a property that their solutions are continuous and single-valued during short time only (even for rather smooth initial data). After that the so-called gradient catastrophe occurs (see, e.g.,[10]), and one has to introduce strong discontinuities. Solutions of viscous conservation laws have apparently no such a property. This is indirectly confirmed by numerous results (e.g.,[27–30]) concerning global existence theorems for the Navier-Stokes equations.In this connection, we especially refer to interesting results in[30] where the global existence and uniqueness of the weak solution of the one-dimensional Navier-Stokes equations written in the Lagrangian coordinates has been proved for the case of discontinuous initial data. Under certain natural restrictions on the initial data it was shown that shock discontinuities do not arise in solutions of the Navier-Stokes equations.At the same time, it should be noted that in some works (their number is not small) the discontinuous approach is nevertheless used for shock waves in a viscous gas. For example, to estimate the influence of a small viscosity to the evolution of perturbations of planar gas dynamic shock waves it is assumed in[31] that one can neglect the width of the shock layer. Therefore, as for an inviscid gas, the problem on the evolution of perturbations is reduced in[31] to the study of a linear initial boundary value problem with boundary conditions on a shock front obtained by the linearization of the generalized Rankine-Hugoniot relations. Another example is the numerical analysis of two-dimensional steady viscous flows near blunt bodies[32] (we just refer to[32] as to a typical paper from numerous computational works relating to the subject under discussion). To bound essentially the calculated domain, where solutions of the compressible Navier-Stokes equations are sought, one introduces a bow shock that is treated in[32] as a strong discontinuity on which surface the generalized Rankine-Hugoniot conditions hold. Moreover, steady flows were being computed in[32] by the stabilization method, i.e., steady-state solutions of the Navier-Stokes equations were being sought as a limit of unsteady ones under

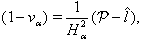

.In[33–35], on the example of the compressible Navier-Stokes equations the groundlessness of the approach based on the consideration of shock waves in a viscous gas as fictitious surfaces of strong discontinuity was shown. It appears that this conclusion can be already drawn according to the linear analysis. For this purpose one studies the initial boundary value problem (IBVP) obtained by the linearization of the Navier-Stokes equations and the jump conditions with respect to their piecewise constant solution. This piecewise constant solution describes the following flow regime for a viscous gas: a supersonic steady viscous flow (for

.In[33–35], on the example of the compressible Navier-Stokes equations the groundlessness of the approach based on the consideration of shock waves in a viscous gas as fictitious surfaces of strong discontinuity was shown. It appears that this conclusion can be already drawn according to the linear analysis. For this purpose one studies the initial boundary value problem (IBVP) obtained by the linearization of the Navier-Stokes equations and the jump conditions with respect to their piecewise constant solution. This piecewise constant solution describes the following flow regime for a viscous gas: a supersonic steady viscous flow (for ) is separated from a subsonic one (for

) is separated from a subsonic one (for ) by a planar shock discontinuity (with the equation

) by a planar shock discontinuity (with the equation ). It was shown in[33–35] that this planar shock wave is unstable depending not on the character of linearized boundary conditions at

). It was shown in[33–35] that this planar shock wave is unstable depending not on the character of linearized boundary conditions at . This is a direct consequence of the fact that the number of independent parameters determining an arbitrary perturbation of the shock front is greater than that of the linearized boundary conditions. That is, the shock wave in a viscous gas viewed as a surface of strong discontinuity is like nonevolutionary (undercompressive) discontinuities in ideal media (see[36,37]).Mathematically, the exponentially increasing particular solutions constructed in[33–35] for establishing linear instability are, actually, Hadamard-type examples (see, e.g.,[14,38]) that indicate the ill-posedness of the linearized stability IBVP mentioned above. The discovered instability can be also treated as an indirect proof of the inadmissibility of steady-state calculations for viscous blunt body flows with a bow shock discontinuity. From the physical point of view, this means the practical unrealizability of the steady flow regime for a viscous gas described above.At the same time, accounting for some advantages of the discontinuous approach (especially for numerical calculations), one would like to modify this approach so that it might be applied (together with the stabilization method) with a mathematical ground for steady-state calculations for blunt body flows with dissipation. In[39,40], on the example of the linearized stability problem for the shock discontinuity in a viscous gas the idea of such a modification was proposed for the one-dimensional case. The essence of this idea is that for the original shock front problem one writes additional boundary conditions so that for the modified problem the steady flow regime with a shock wave described above becomes asymptotically stable (by Lyapunov). That is, at least on the linearized level this might justify the stabilization method which can now be applied for finding (e.g., numerically) steady flow regimes for a viscous gas with a shock wave. The mentioned additional boundary conditions were suggested to be written with regard to an a priori information about steady-state solutions of the Navier-Stokes equations being sought by the stabilization method.In the present paper we consider a curvilinear shock wave.

. This is a direct consequence of the fact that the number of independent parameters determining an arbitrary perturbation of the shock front is greater than that of the linearized boundary conditions. That is, the shock wave in a viscous gas viewed as a surface of strong discontinuity is like nonevolutionary (undercompressive) discontinuities in ideal media (see[36,37]).Mathematically, the exponentially increasing particular solutions constructed in[33–35] for establishing linear instability are, actually, Hadamard-type examples (see, e.g.,[14,38]) that indicate the ill-posedness of the linearized stability IBVP mentioned above. The discovered instability can be also treated as an indirect proof of the inadmissibility of steady-state calculations for viscous blunt body flows with a bow shock discontinuity. From the physical point of view, this means the practical unrealizability of the steady flow regime for a viscous gas described above.At the same time, accounting for some advantages of the discontinuous approach (especially for numerical calculations), one would like to modify this approach so that it might be applied (together with the stabilization method) with a mathematical ground for steady-state calculations for blunt body flows with dissipation. In[39,40], on the example of the linearized stability problem for the shock discontinuity in a viscous gas the idea of such a modification was proposed for the one-dimensional case. The essence of this idea is that for the original shock front problem one writes additional boundary conditions so that for the modified problem the steady flow regime with a shock wave described above becomes asymptotically stable (by Lyapunov). That is, at least on the linearized level this might justify the stabilization method which can now be applied for finding (e.g., numerically) steady flow regimes for a viscous gas with a shock wave. The mentioned additional boundary conditions were suggested to be written with regard to an a priori information about steady-state solutions of the Navier-Stokes equations being sought by the stabilization method.In the present paper we consider a curvilinear shock wave.2. Preliminary Information

2.1. The System Describing Gas Dynamics

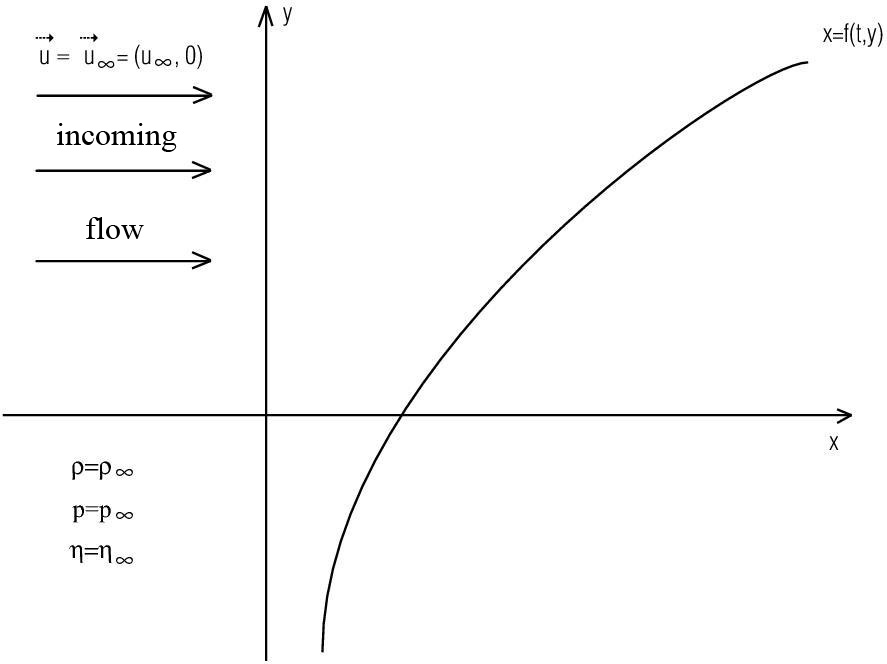

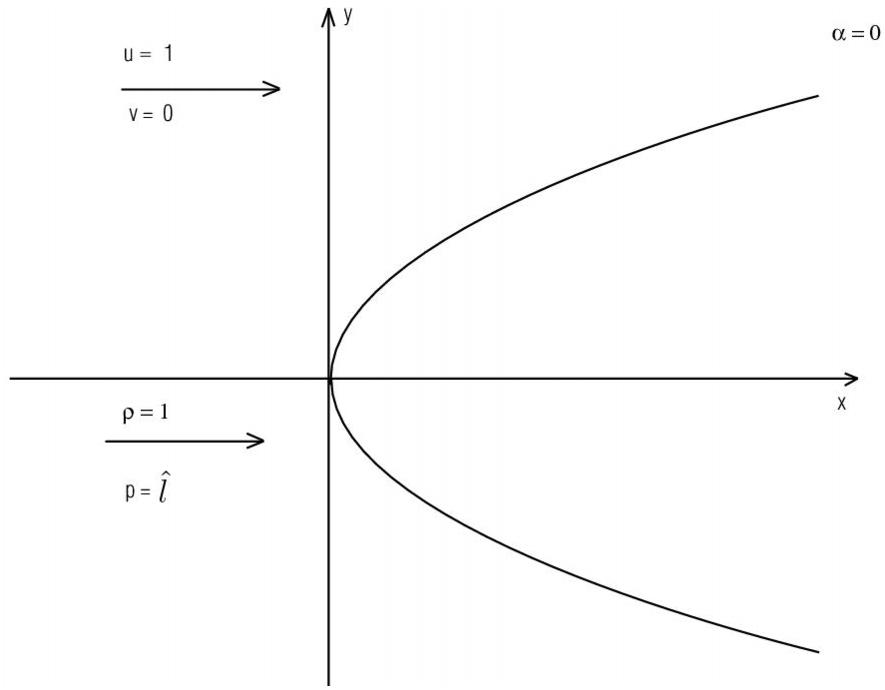

- Recall that in[33,39] the stability of shock waves in a compressible viscous gas described by the well-known Navier-Stokes equations was studied. Let us consider the same flow regime as in[33,39] (see Fig. 1): the supersonic steady viscous flow is separated from the disturbed flow by a shock wave with the equation

| (1) |

is the time,

is the time,  is the Cartesian coordinate system (in this paper we restrict ourselves to the consideration of the planar case).

is the Cartesian coordinate system (in this paper we restrict ourselves to the consideration of the planar case). | Figure 1. Viscous gas flow with a shock wave |

| (2) |

is the gas density,

is the gas density,  is the specific volume,

is the specific volume,  are the Cartesian components of the velocity vector

are the Cartesian components of the velocity vector ,

,  is the pressure,

is the pressure, are constants,

are constants, ,

,  are the first and second viscosity coefficients (see[39,41]),

are the first and second viscosity coefficients (see[39,41]), is the Reynolds number (see[41]),

is the Reynolds number (see[41]), is the temperature,

is the temperature,  is the Prandtl number (see[41]),

is the Prandtl number (see[41]), is the heat conductivity,

is the heat conductivity, ;

; ,

,  are the specific heat capacities,

are the specific heat capacities, the following scaling factors were used to define the dimensionless time

the following scaling factors were used to define the dimensionless time , the coordinates

, the coordinates ,

,  , the density

, the density , the velocity components

, the velocity components ,

,  , the pressure

, the pressure  (see Fig. 1):

(see Fig. 1):  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , where

, where  is a characteristic length (see also Remark 2.1); the dimensionless viscosity coefficients

is a characteristic length (see also Remark 2.1); the dimensionless viscosity coefficients ,

,  are defined by using

are defined by using  as the scaling factor; the viscosity coefficient

as the scaling factor; the viscosity coefficient  depends on

depends on  according to the power law (see[41])

according to the power law (see[41])  | (3) |

is the Mach number for the upstream flow,

is the Mach number for the upstream flow,  is a constant.

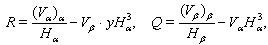

is a constant.2.2. Rankine-Hugoniot Conditions

- On the surface of shock wave (1) generalized Rankine-Hugoniot conditions hold (see[33,39]). Using some cumbersome manipulations they can be reduced to the following

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

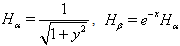

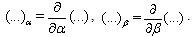

2.3. The Problem Written in the Curvilinear Coordinate System

- Further we will need the Navier-Stokes equations (2) rewritten in orthogonal curvilinear coordinates

:

:  | (8) |

and

and  in (8) are the dimensionless coordinates. Formulae (8) can be rewritten in the dimensional form as

in (8) are the dimensionless coordinates. Formulae (8) can be rewritten in the dimensional form as | (8a) |

is a characteristic length (see Remark 2.1). The curvilinear coordinates

is a characteristic length (see Remark 2.1). The curvilinear coordinates ,

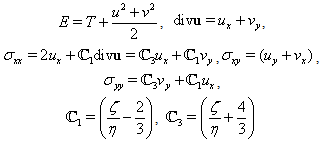

,  are chosen so that the front of the shock wave is described in the stationary case by the equation (see Fig. 2)

are chosen so that the front of the shock wave is described in the stationary case by the equation (see Fig. 2) | (1a) |

| Figure 2. Front of the shock wave |

can be taken as the characteristic length

can be taken as the characteristic length  We rewrite the Navier-Stokes equations in the coordinates

We rewrite the Navier-Stokes equations in the coordinates  in the following nonconservative form (see[41]):

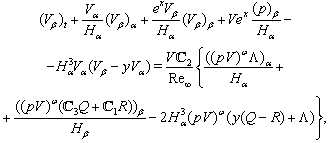

in the following nonconservative form (see[41]):  | (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

,

,  are the physical components of the velocity vector

are the physical components of the velocity vector  in the curvilinear coordinates

in the curvilinear coordinates  related to the Cartesian components

related to the Cartesian components ,

,  as

as  | (13) |

,

,  are the so-called contravariant components of the velocity vector

are the so-called contravariant components of the velocity vector  (see[42]);

(see[42]);  | (14) |

| (15) |

are the Lamé coefficients (see[42]),

are the Lamé coefficients (see[42]), Remark 2.2. Taking into account formulae (13), we can rewrite equations (9)–(12) as

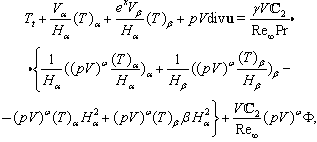

Remark 2.2. Taking into account formulae (13), we can rewrite equations (9)–(12) as  | (9a) |

| (10a) |

| (11a) |

| (12a) |

the values of

the values of ,

, are calculated by using (14), (15). Remark 2.3. We are also interested in stationary solutions to equations (9)–(12) (or (9a)–(12a)) with boundary conditions set at the front of the shock wave

are calculated by using (14), (15). Remark 2.3. We are also interested in stationary solutions to equations (9)–(12) (or (9a)–(12a)) with boundary conditions set at the front of the shock wave  (see Fig. 2). In the stationary case conditions (4)–(7) take the following form:

(see Fig. 2). In the stationary case conditions (4)–(7) take the following form:  | (4a) |

| (5a) |

| (6a) |

| (7a) |

.

. 3. Solving the Stationary Navier-Stokes Equations in a Neighborhood of the Line

3.1. Additional Assumptions

- The system of equations (9a)–(12a) is too complicated. Let us modify it in a certain way in the stationary case. To simplify further calculations we will assume thata) the viscosity coefficient

(see formula (3)) is constant behind the shock wave

(see formula (3)) is constant behind the shock wave :

:  | (3a) |

,

,  are constants;b)

are constants;b)  , i.e., the Prandtl number

, i.e., the Prandtl number ;c)

;c)  , where

, where  is a new dependent variable;d) the functions

is a new dependent variable;d) the functions ,

, are denoted as

are denoted as ,

, .Then in the region

.Then in the region  the system (9a)–(12a) in the stationary case can be rewritten as

the system (9a)–(12a) in the stationary case can be rewritten as | (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

,

, For

For  the solution of system (16)–(19) should satisfy relations (4a)–(7a) which under assumptions a) – d) cited above can be rewritten as follows:

the solution of system (16)–(19) should satisfy relations (4a)–(7a) which under assumptions a) – d) cited above can be rewritten as follows:  | (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

In addition, we will assume that the functions

In addition, we will assume that the functions  ,

,  satisfy the so-called ''soft condition'' (see[41]) as

satisfy the so-called ''soft condition'' (see[41]) as :

:  | (24) |

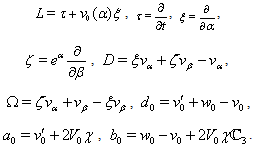

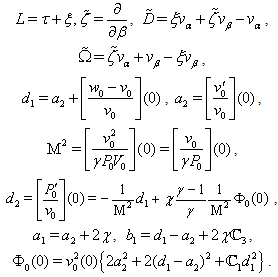

3.2. The Taylor Expansion with Respect to the Argument β

- Further we will simplify the nonstationary system (9a)–(12a) using stationary solutions

,

,  in a neighborhood of the line

in a neighborhood of the line  for definition of system’s coefficients. The functions

for definition of system’s coefficients. The functions ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  are even with respect to the argument

are even with respect to the argument  (see Fig. 2). Therefore, in a neighborhood of the line

(see Fig. 2). Therefore, in a neighborhood of the line  we will search them in the form of the following series (see[43,44]):

we will search them in the form of the following series (see[43,44]):  | (25) |

,

,  into series with respect to the variable

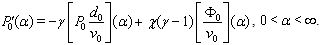

into series with respect to the variable .Substituting expansion (25) into (16)–(24) and equating the coefficients at the same powers of beta

.Substituting expansion (25) into (16)–(24) and equating the coefficients at the same powers of beta  , we obtain a relation for determining the functions

, we obtain a relation for determining the functions ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , etc. in series (25). Equating the coefficients at

, etc. in series (25). Equating the coefficients at , we have:

, we have:  | (26) |

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

;

;  | (30) |

| (31) |

| (32) |

| (33) |

;

;  | (34) |

ect.Remark 3.2. As follows from (26)–(34), for the determination of the functions

ect.Remark 3.2. As follows from (26)–(34), for the determination of the functions ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  we have to know the functions

we have to know the functions  ,

,  ,

, . Further, assuming in these relations that

. Further, assuming in these relations that ,

,  ,

,  , we will consider an approximate solution of the problem (26)–(34). Remark 3.3. We set in formula (3a) that

, we will consider an approximate solution of the problem (26)–(34). Remark 3.3. We set in formula (3a) that ,

, . From (33), (31) we have:

. From (33), (31) we have: | (35) |

. Then, it follows from (30), (31), (35) that

. Then, it follows from (30), (31), (35) that  | (36) |

.

. 3.3. The Boundary-Value Problem of Second Order for the Components of Velocity Vector

- Let us return to the boundary-value problem (26)–(34). From (26), (27) we have:

| (37) |

and the quantity

and the quantity  can be expressed in terms of

can be expressed in terms of  by formula (36). Let us rewrite equations (28), (29) as follows:

by formula (36). Let us rewrite equations (28), (29) as follows: | (38) |

| (39) |

,

,  The boundary conditions for equations (38), (39) follow from (36), (32), (34):

The boundary conditions for equations (38), (39) follow from (36), (32), (34):  | (40) |

| (41) |

| (42) |

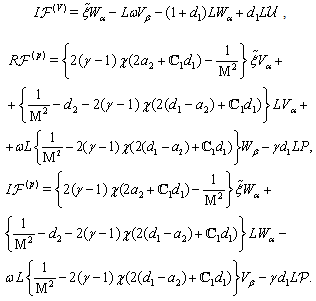

4. The Linearization of Nonstationary Problem for System (9a)–(12a)

4.1. The Linarization of Nonstationary Equations (9a)–(12a)

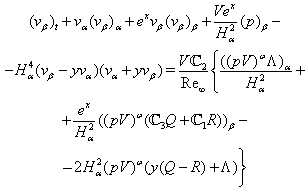

- Let us linearize of system (9a)–(12a) about the basic solution (25) and freeze then the coefficients of the linearized system on the line

. Denoting small perturbations by the same letters, we finally obtain:

. Denoting small perturbations by the same letters, we finally obtain:  | (43) |

| (44) |

| (45) |

| (46) |

System (43)–(46) is considered in the domain

System (43)–(46) is considered in the domain  (at infinity the sought functions tends to zero).Let us simplify system (43)–(46) by freezing the functions

(at infinity the sought functions tends to zero).Let us simplify system (43)–(46) by freezing the functions  and

and  at the point

at the point  and making the change of

and making the change of  (below we drop tilde and again write

(below we drop tilde and again write  instead of

instead of ). We get finally that

). We get finally that | (43a) |

| (45a) |

| (46a) |

4.2. The Linearization of Stationary Boundary Conditions (4a)–(7a)

- Let us now formulate boundary conditions at

. To this end we linearize conditions (4a)–(7a) posed at

. To this end we linearize conditions (4a)–(7a) posed at , where the function

, where the function  is the small perturbation of the shock front which unperturbed position is

is the small perturbation of the shock front which unperturbed position is . Freezing the coefficients at

. Freezing the coefficients at we will finally obtain

we will finally obtain :

:  | (47) |

| (48) |

| (49) |

| (50) |

Remark 4.1. According to [33,39] for the determination of the function

Remark 4.1. According to [33,39] for the determination of the function  describing the small perturbation of the shock front

describing the small perturbation of the shock front  we will add to (43a)–(46a), (47)–(50) the equation in the form (see, for example,[33,39])

we will add to (43a)–(46a), (47)–(50) the equation in the form (see, for example,[33,39])  where

where  is a constant.

is a constant.  where

where  .Remark 4.3. We also assume that the small perturbations (see (24)).In the section 5 a new computational algorithm for finding stationary approximate solutions of the initial-boundary value problem (43a)–(46a), (47)–(51) is described, where we also present results of numerical experiments.

.Remark 4.3. We also assume that the small perturbations (see (24)).In the section 5 a new computational algorithm for finding stationary approximate solutions of the initial-boundary value problem (43a)–(46a), (47)–(51) is described, where we also present results of numerical experiments.5. A New Computational Algorithm for Solving Boundary-Value Problems of Second Order

- Now we will propose a new numerical algorithm for solving the problem (38)–(42). In numerical calculations we pass from infinite segment

to a finite one and assume that

to a finite one and assume that , where

, where  is a large enough number. We make the change of variable

is a large enough number. We make the change of variable . Let

. Let  (do not forget that

(do not forget that  ) , then

) , then  . Note also that

. Note also that  has no physical meaning and dimension and the new notation

has no physical meaning and dimension and the new notation  is not equal to that from section 2 and concerns only sections 5 and 6.

is not equal to that from section 2 and concerns only sections 5 and 6.5.1. The Nonstationary Regularization and the Stabilization Method

- Introducing the notations

, we rewrite the boundary-value problem (38)–(42) as follows:

, we rewrite the boundary-value problem (38)–(42) as follows:  | (52) |

| (53) |

and

and  | (54) |

. Here

. Here

For searching approximate solutions of the boundary-value problem (52)–(54) we will use the stabilization method. To this end let us apply to the equations of system (52) the nonstationary regularization proposed in the[45,46]. As a result, we obtain the system of nonstationary equations

For searching approximate solutions of the boundary-value problem (52)–(54) we will use the stabilization method. To this end let us apply to the equations of system (52) the nonstationary regularization proposed in the[45,46]. As a result, we obtain the system of nonstationary equations  | (55) |

| (56) |

and t plays the role of time, i.e., we assume further that the unknowns

and t plays the role of time, i.e., we assume further that the unknowns ,

,  depend also on the variable t:

depend also on the variable t: .Remark 5.1. The main idea of the stabilization method is described, for example, in[47]. In our case for the implementation of the stabilization method we should discretize the nonstationary equations (55), (56) by time and perform numerical computations until the solution ''stabilized''. In other words, the algorithm using this method will stop only when the norm of the difference of the solutions at next and previous time layers becomes small enough. Thus, we search a solution of problem (52)–(54) in the form of a limit as

.Remark 5.1. The main idea of the stabilization method is described, for example, in[47]. In our case for the implementation of the stabilization method we should discretize the nonstationary equations (55), (56) by time and perform numerical computations until the solution ''stabilized''. In other words, the algorithm using this method will stop only when the norm of the difference of the solutions at next and previous time layers becomes small enough. Thus, we search a solution of problem (52)–(54) in the form of a limit as  of the solutions of the nonstationary equations (55), (56) with the boundary conditions (53), (54). For the application of the stabilization method it is necessary to specify initial data for system (55), (56). Further we assume that

of the solutions of the nonstationary equations (55), (56) with the boundary conditions (53), (54). For the application of the stabilization method it is necessary to specify initial data for system (55), (56). Further we assume that  | (57) |

where

where  is the time-step of the greed.Approximating the derivatives

is the time-step of the greed.Approximating the derivatives  ,

,  in (55), (56) by the expressions

in (55), (56) by the expressions  and

and  respectively, we obtain

respectively, we obtain  | (58) |

| (59) |

5.2. The Spline-Function Technique

- We will seek a solution of equations (58), (59) in the form of cubic

interpolation splines (see[45,46,48]). For example, let us write the approximate solution of equation (58) in the following way:

interpolation splines (see[45,46,48]). For example, let us write the approximate solution of equation (58) in the following way: | (60) |

The cubic spline (60) should be continuous together with its first derivative on the whole segment

The cubic spline (60) should be continuous together with its first derivative on the whole segment  (the second derivative is continuous according to the definition of spline (60)).The first derivative of the cubic spline has the following form:

(the second derivative is continuous according to the definition of spline (60)).The first derivative of the cubic spline has the following form:  Then, computing the aggregates

Then, computing the aggregates  where

where

and equating them, one gets

and equating them, one gets  | (61) |

Assuming in (58)

Assuming in (58)  and substituting

and substituting  from (58) into (61), one gets the following three-pointed difference scheme:

from (58) into (61), one gets the following three-pointed difference scheme:  | (62) |

The derivatives

The derivatives  at the grid nodes (i.e., at the points

at the grid nodes (i.e., at the points  ) are required for computing the right-hand sides

) are required for computing the right-hand sides  and

and  on the next time layer. These derivatives can be computed using spline (60).Since

on the next time layer. These derivatives can be computed using spline (60).Since  where

where  , then

, then

Using similar arguments, we get the three-pointed difference scheme

Using similar arguments, we get the three-pointed difference scheme  | (63) |

for finding a solution of equation (59), where

for finding a solution of equation (59), where  The derivatives

The derivatives  can be found as follows:

can be found as follows:

Replacing in (53), (54) the derivatives

Replacing in (53), (54) the derivatives

,

,  ,

,  by their difference analogues

by their difference analogues  ,we obtain the boundary conditions on the

,we obtain the boundary conditions on the  th time layer

th time layer | (64) |

th layer

th layer  | (65) |

5.3. The Use of Sweep Method

- Equations (62), (63) with the boundary conditions (64), (65) can be solved by using the sweep method. Let us describe the application of this method on the example of problem (62), (64). The computations for scheme (63) with the boundary conditions (65) can be done in the same manner.We write down system (62) in the form

| (66) |

| (67) |

| (68) |

Remark 5.2. Problem (63), (65) can be also easily reduced to the problem of form (66)–(68). According to the idea of the sweep method we search a solution of (66)–(68) as

Remark 5.2. Problem (63), (65) can be also easily reduced to the problem of form (66)–(68). According to the idea of the sweep method we search a solution of (66)–(68) as  | (69) |

:

:  | (70) |

we take the values of the sweep coefficients

we take the values of the sweep coefficients  from the boundary condition (67). Thus, in the cycle of the forward sweep we can find the coefficients

from the boundary condition (67). Thus, in the cycle of the forward sweep we can find the coefficients  by formulas (70). Then, using the boundary condition (68) and formula (69), we can compute the solution at the point

by formulas (70). Then, using the boundary condition (68) and formula (69), we can compute the solution at the point  :

:  At last, knowing

At last, knowing  and the coefficients of the sweep method, we can find a solution of problem (62), (64) by formula (69) in the cycle of the backward sweep.Remark 5.3. Using the same arguments, we can find a solution of problem (63), (65) by applying again the sweep method (see Remark 5.2).

and the coefficients of the sweep method, we can find a solution of problem (62), (64) by formula (69) in the cycle of the backward sweep.Remark 5.3. Using the same arguments, we can find a solution of problem (63), (65) by applying again the sweep method (see Remark 5.2). 5.4. The Computational Scheme and Numerical Results

- As a result, the scheme of searching approximate solutions of system (55), (56) at each time layer is the following. Starting from the values of unknowns obtained on the

th time layer we compute the values of variables of the problem and the right-hand side

th time layer we compute the values of variables of the problem and the right-hand side  at each point of the space greed. Then we find the solution

at each point of the space greed. Then we find the solution  of equation (55) with boundary conditions (53), (54) by using the sweep method. After that we compute the values of variables and right-hand side

of equation (55) with boundary conditions (53), (54) by using the sweep method. After that we compute the values of variables and right-hand side  by taking into account the obtained

by taking into account the obtained  and solve the boundary-value problem (56), (53), (54). At last, we get the solution

and solve the boundary-value problem (56), (53), (54). At last, we get the solution  of system (55), (56) at the

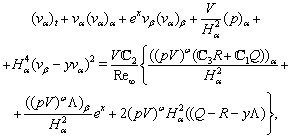

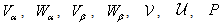

of system (55), (56) at the  th time layer. Then, we pass to the next time layer.According to the idea of the stabilization method (see Remark 5.1), these actions should be repeated until the solution becomes ''stabilized''. The obtained values of unknowns are exactly the desired approximate solution of the boundary-value problem (52)–(54).For the organization of computations by the proposed scheme it is necessary to specify the list of physical and numerical parameters. In Table 1 we give the description of each parameter and the range of its values.

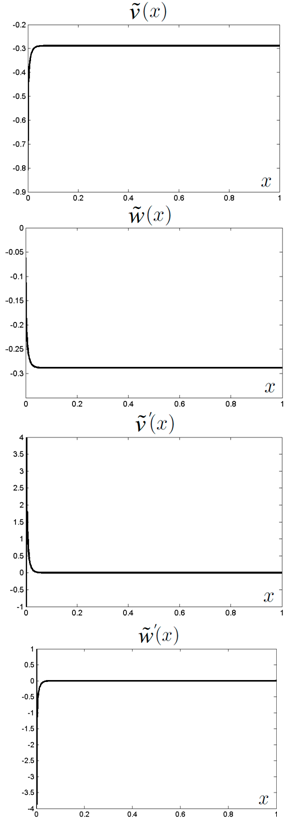

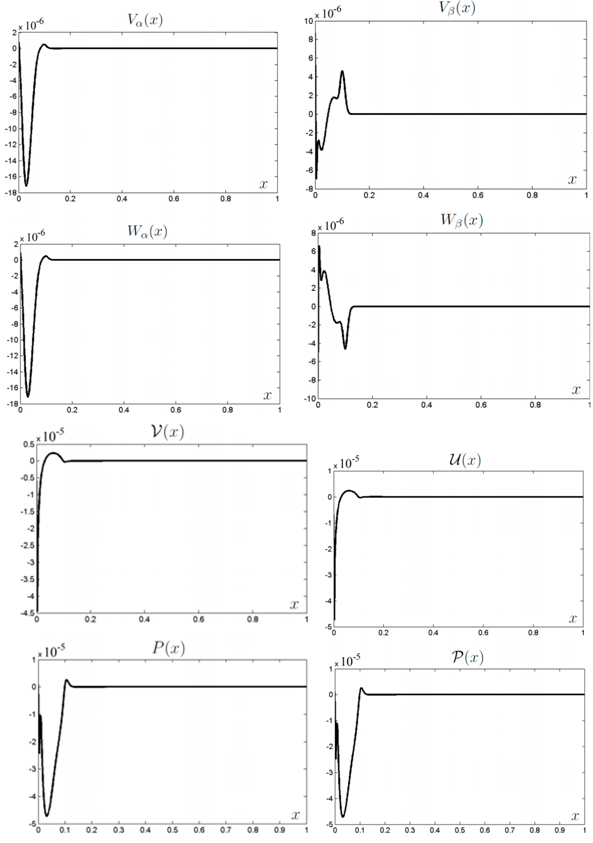

th time layer. Then, we pass to the next time layer.According to the idea of the stabilization method (see Remark 5.1), these actions should be repeated until the solution becomes ''stabilized''. The obtained values of unknowns are exactly the desired approximate solution of the boundary-value problem (52)–(54).For the organization of computations by the proposed scheme it is necessary to specify the list of physical and numerical parameters. In Table 1 we give the description of each parameter and the range of its values. | Figure 3. The functions  and and  and their derivatives obtained after computations with the parameters and their derivatives obtained after computations with the parameters  , ,  , ,  , ,  , ,  , ,  , ,  , ,  |

|

. The algorithm stops if

. The algorithm stops if  Some results of computations are given in Fig. 3.

Some results of computations are given in Fig. 3.6. Numerical Results Showing the Stability of Shock Wave

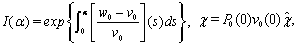

6.1. The Fourier Transform for Nonstationary Problem (43a)–(46a), (47)–(51)

- Now let us describe the algorithm of searching approximate stationary solutions of equations (43a)–(46a) for small perturbations with the boundary condition (47)–(51). As it was made in the section 5 the stationary solution will be find with a help of the stabilization method. Following section 5, we assume that

, where

, where  is large enough, replace the variable

is large enough, replace the variable  by

by  and denote

and denote  ,

,  (do not forget that

(do not forget that  ). Then

). Then  Assume that at

Assume that at  the unknowns of problem (43a)–(46a) satisfy initial data (see Remark 4.2).Remark 6.1. In the section 4 the computational algorithm for searching the values of functions

the unknowns of problem (43a)–(46a) satisfy initial data (see Remark 4.2).Remark 6.1. In the section 4 the computational algorithm for searching the values of functions  and

and  was described in detail. In this case the functions

was described in detail. In this case the functions  and

and  needed for the determination of the coefficients of equations (43a)–(46a) can be expressed as follows:

needed for the determination of the coefficients of equations (43a)–(46a) can be expressed as follows:  Let

Let  be the Fourier transform of the velocity component

be the Fourier transform of the velocity component  with respect to the variable

with respect to the variable  , where

, where  is the Fourier parameter (the notation

is the Fourier parameter (the notation  corresponds only to this section, in other sections

corresponds only to this section, in other sections  is a constant from (3))::

is a constant from (3))::  | (71) |

Similarly we can find the Fourier transforms of the unknowns

Similarly we can find the Fourier transforms of the unknowns ,

,  ,

,  and their derivatives. Applying then the Fourier transform in form (71) to each equation in (43a)–(46a) and each condition in (47)–(51) and dropping the hats, we get the system

and their derivatives. Applying then the Fourier transform in form (71) to each equation in (43a)–(46a) and each condition in (47)–(51) and dropping the hats, we get the system  | (72) |

| (73) |

and

and  | (74) |

.Assuming

.Assuming  and

and  to be complex-valued functions in the form

to be complex-valued functions in the form  we substitute them into (72)–(74) and equate the corresponding real and imaginary parts in the obtained relations. Finally we derive

we substitute them into (72)–(74) and equate the corresponding real and imaginary parts in the obtained relations. Finally we derive  | (75) |

| (76) |

| (77) |

| (78) |

The boundary conditions for (75)–(78) at

The boundary conditions for (75)–(78) at  obtained from (73) have the form

obtained from (73) have the form  | (79) |

| (80) |

| (81) |

| (82) |

| (83) |

| (84) |

.

.6.2. The Numerical Solution of Boundary-Value Problems

- Let the function

be one of the unknowns

be one of the unknowns  ,

,  ,

,  and the function

and the function  be the corresponding right-hand side

be the corresponding right-hand side ,

,  , or

, or . Then, the equations (75), (76) can be written in the general form

. Then, the equations (75), (76) can be written in the general form  | (85) |

| (86) |

| (87) |

,

,  ,

,  can be written after elementary arithmetical transformations of equations (75), (76) and the boundary conditions (79), (80).Let the function

can be written after elementary arithmetical transformations of equations (75), (76) and the boundary conditions (79), (80).Let the function  be one of the unknowns

be one of the unknowns ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and the function

and the function  be the corresponding right-hand side

be the corresponding right-hand side ,

,  ,

,  or

or . Then, equations (77), (78) can be written in the general form

. Then, equations (77), (78) can be written in the general form  | (88) |

| (89) |

takes the values

takes the values ,

,  ,

,  or

or  (see (81), (82)).Our goal is finding approximate solutions of problem (75)–(84) with certain initial data. To this end we use the idea of the method of lines and discretize the nonstationary equations (85), (88) with respect to the variable tIntroduce the notations

(see (81), (82)).Our goal is finding approximate solutions of problem (75)–(84) with certain initial data. To this end we use the idea of the method of lines and discretize the nonstationary equations (85), (88) with respect to the variable tIntroduce the notations

where

where  is the step of the time greed.Approximating the derivatives

is the step of the time greed.Approximating the derivatives ,

,  in (85), (88) by expressions

in (85), (88) by expressions  and

and  respectively, one obtains

respectively, one obtains  | (90) |

,

,  ,

,  | (91) |

a uniform grid with the nodes

a uniform grid with the nodes ,

,  and the step

and the step , where

, where  is the number of greed nodes. Let

is the number of greed nodes. Let ,

,  ,

,  and

and  be the values of the unknowns

be the values of the unknowns ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  at the

at the  th greed node. Considering the boundary conditions (86), (87) on the n time layer and replacing there the derivative

th greed node. Considering the boundary conditions (86), (87) on the n time layer and replacing there the derivative  on the boundaries

on the boundaries  and

and  by its difference analogues

by its difference analogues  and

and , one obtains the following boundary-value problem for equation (90):

, one obtains the following boundary-value problem for equation (90):  | (92) |

at the point

at the point  by its difference analogue

by its difference analogue ,

,  and taking into account (89), one gets

and taking into account (89), one gets  or

or  | (93) |

is the value of

is the value of  at the point

at the point  . Thus, knowing the quantities

. Thus, knowing the quantities  and

and  from the previous time layer at each point

from the previous time layer at each point  and

and  from the current layer and using (93), we can find

from the current layer and using (93), we can find  at the current time layer.

at the current time layer.6.3. The Computational Scheme and the Results Obtained

- Thus, at each time layer we can find the values of the unknowns

of problem (75)–(84) as solutions of the boundary-value problems (92), (93). Then, using these values, we recompute the right-hand sides

of problem (75)–(84) as solutions of the boundary-value problems (92), (93). Then, using these values, we recompute the right-hand sides  ,

,  of equations (75)–(78) and pass to the next time layer (on the first layer the values of the right-hand sides can be found from the initial data). Choosing n large enough, we can finally find the approximate stationary solution of problem (75)–(84) and, hence, the approximate stationary solution of the original problem (43a)–(46a), (47)–(51) for large enough values of time.

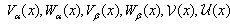

of equations (75)–(78) and pass to the next time layer (on the first layer the values of the right-hand sides can be found from the initial data). Choosing n large enough, we can finally find the approximate stationary solution of problem (75)–(84) and, hence, the approximate stationary solution of the original problem (43a)–(46a), (47)–(51) for large enough values of time. | Figure 4. The functions , , and and  obtained in the computations with the parameters obtained in the computations with the parameters , ,  , ,  , ,  (see Table I) (see Table I) |

and

and  . These graphs show that the obtained values are sufficiently close to zero. This fact is the evidence of the stability of the shock wave in a compressible viscous gas with given parameters.

. These graphs show that the obtained values are sufficiently close to zero. This fact is the evidence of the stability of the shock wave in a compressible viscous gas with given parameters.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are indebted to prof. Yu.L.Trakhinin for the help in the preparation of the manuscript of this paper, to prof. D. L. Tkachev and Ph. D. R. S. Bushmanov.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML

, Ann. Scuola Norm. Super. Pisa, N 10, 1983, pp. 357-427.

, Ann. Scuola Norm. Super. Pisa, N 10, 1983, pp. 357-427.