-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2019; 8(3): 53-58

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20190803.01

Trend, Manifestations and Outcome of Falciparum Malaria Infection in Wad-Medani Teaching Hospital in the Central Region of Sudan

Sawsan A. Omer1, Mohammed I. Malik2, Fawkia E. Zahran3, Sadiq M. Sharaf4

1Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Gezira University, Medical Consultant, Sudan

2Assistant Professor, Faculty of Medicine, Gezira University, Consultant Gastroentolog, Wad-Medani Teaching Hospital, Sudan

3Internal Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine for girls, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

4Gastroenterology Specialist Wad-Medani Teaching Hospital Sudan

Correspondence to: Fawkia E. Zahran, Internal Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine for girls, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

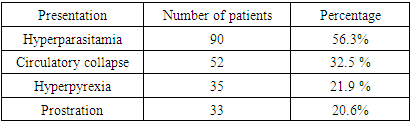

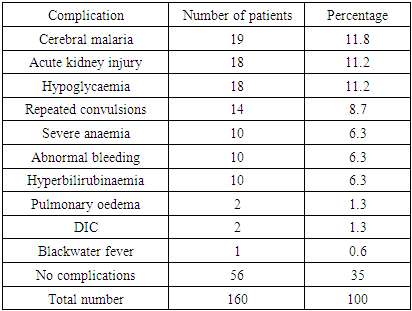

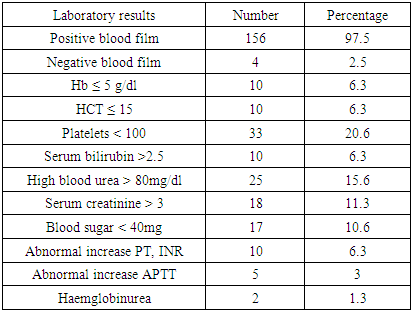

Background: Malaria is one of the most common diseases affecting humans worldwide. It remains a major global public health and a major cause of morbidity and mortality in tropical and subtropical countries. Plasmodium falciparum malaria is the most dangerous and fatal form of illness, and it is the most common species prevalent in Sudan throughout the year. Gastrointestinal manifestations are common in malaria endemic areas. Malaria occasionally presents with both typical and atypical symptoms and signs, and there is an increase burden on health services in hospitals, due to large spectrum of falciparum malaria presentation and outcome, especially in Gezira area in Sudan. Objectives: To assess the trend, manifestations and outcome of falciparum malaria infection in patients admitted to medical wards. Methods: This is descriptive, prospective, cross sectional hospital-based study, conducted in Wad Medani Teaching Hospital in the central region of Sudan in the period of December 2014 to May 2015. Results: A total of 160 patients were admitted with severe malaria during period from December 2014 to May 2015. The age of study populations ranged from 15 - 80 years, with mean age (43.11), with the most affected patients in age group 15 - 45 years. Males were 86 (53.8%) and females 74 (46.3%). The main manifestations and complication of severe falciparum malaria in this study were: hyperparasitemia which present in 90 (56.3%), then Hypotension or circulatory collapse was observed in 52 (32.5%), hyperpyrexia was seen in 35 (21.9%), prostration and weakness seen in 33 (20.6%), cerebral malaria with loss of consciousness seen in 19 (11.9%), acute kidney injury (AKI) was seen in 18 (11.3%), hypoglycemia was seen in 18 (11.3%), repeated convulsions ≥ 3 frequency occurred in 14(8.8%), severe anemia was seen in 10(6.3%), abnormal bleeding occurred in 10(6.3%), and hyperbilirubinemia also in 10 (6.3%). Pulmonary oedema was found in 2 cases (1.3%), and disseminate intravascular coagulation (DIC) in 2 (1.3%), blackwater fever in one case (0.6%). Other complications like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and acidosis were not reported in this study. Patients who received quinine hydrochloride salt via intravenous infusion were 153 (95.6%), and who received artemether injection were 7(4.4%). Some patients received supportive management according to their presentation. The main duration of hospital stay was 3-5 days in 87 (54.4%). The outcome was as follows: 154 (96.3%) improved and were discharged in a good condition, and Six patients (3.8%) died. Conclusion: Falciparum malaria is more among younger adult age group and male. The main manifestations and complications of severe falciparum malaria infection were hyperparasitemia, hypotension, hyperpyrexia, prostration and weakness, cerebral malaria, AKI then hypoglycemia and repeated convulsions, severe anemia. Most of the patients treated with quinine with very good response, and the mortality rate was 3.8%.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, Malaria, Clinical presentation, Complications, Outcome

Cite this paper: Sawsan A. Omer, Mohammed I. Malik, Fawkia E. Zahran, Sadiq M. Sharaf, Trend, Manifestations and Outcome of Falciparum Malaria Infection in Wad-Medani Teaching Hospital in the Central Region of Sudan, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 8 No. 3, 2019, pp. 53-58. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20190803.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Malaria is an endemic disease, according to world health organisation (WHO) there were an estimated 219 million cases of malaria, in 2017 compared to 217 million the year before with mortality rate of 435,000 people mostly children in the African Region. Malaria is caused by several Plasmodium (P) species. Plasmodium falciparum usually causes severe malaria in highly endemic areas [1]. Plasmodium genus are intraerythrocytic protozoa, there are four species of plasmodium, P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae. These parasites are usually transmitted by the bite of an infective female Anopheles species mosquito but it can also be transmitted through exposure to infected blood products, congenital transmission, or laboratory exposure. P. falciparum is more prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa and the most pathogenic malaria sp7ecies and it is most commonly associated with severe illness and death mainly in young children. Mixed infections with multiple species may occur in some areas if more than one species is present in circulation. P. knowlesi, is mainly simian malaria found in Southeast Asia, may rarely affects humans. WHO defines severe malaria as a case of malaria with one or more of the following manifestations: neurologic symptoms, acute kidney injury, severe anemia (hemoglobin [Hb] <7g/dL), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), jaundice, or ≥5% parasitemia. Cases also were counted as severe if the person received treatment for severe malaria (i.e., artesunate, quinidine, or an exchange blood transfusion) despite having no specific severe manifestations reported. All fatal malaria cases were classified as severe [2]. Sporozoites inoculated into the bloodstream of an infected person when anopheline mosquito bites him, then sporozoites enter hepatocytes within an hour then divides and becomes exoerythrocytic merozoites (tissue schizogony). For P. vivax and P. ovale, forms hypnozoites remains dormant in the liver and later may cause malaria; but P. falciparum does not produce hypnozoites. Later merozoites leave the liver and invade erythrocytes and develop into early trophozoites, which are ring shaped. When the trophozoites divide they are called schizonts. The duration of each cycle in P. falciparum is about 48 hours. Destruction of erythrocytes and release of schizonts into the circulation is the main cause of clinical symptoms of malaria. Clinical presentation of malaria may be mild with nonspecific symptoms or could be severe. The majority of patients develop fever (>92% of cases), chills (79%), headaches (70%), and sweating (64%). Other common symptoms include dizziness, malaise, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, mild diarrhea, and dry cough. Physical signs include fever, tachycardia, jaundice, pallor, orthostatic hypotension, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly. Clinical examination may be unremarkable especially in nonimmune persons [3]. Factors that contribute severity of malaria include the parasite species; age of the patient, immunity, general health, and nutritional status of the patient; chemoprophylaxis effects; and time of diagnosis and initiation of treatment. If not treated promptly, malaria may cause multiple organ damage resulting in altered consciousness (cerebral malaria), acute kidney injury and liver failure, respiratory distress, coma and death. Diagnosis of malaria is mainly by peripheral blood film microscopy (gold standard test), polymerase chain reaction, or rapid diagnostic tests. Thick and thin blood films can quickly detect the presence of malaria parasites, determine the species and percentage of red blood cells that are infected, and this is important for choosing the appropriate treatment. If three sets of thick and thin blood films were taken, spaced 12–24 hours apart and were negative for plasmodium then, malaria may be ruled out [2]. Other laboratory findings in malaria include: thrombocytopenia in 60% of cases, hyperbilirubinemia 40%, anemia 30%, and elevated hepatic aminotransferase levels 25%. The leukocyte count is usually normal or low. Cerebral malaria, pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, severe anemia, and/or bleeding are the major complications of malaria and may develop rapidly leading to death if not treated appropriately. The most common metabolic complications are acidosis and hypoglycaemia. So any patient with malaria should be assessed for symptoms and signs of severity and should be treated immediately [3]. Treatment should be initiated as soon as possible. Patients who have severe vomiting or severe malaria should receive parenteral therapy [4]. Chloroquine is used for treatment of P. falciparum but in areas with chloroquine resistance, like the case in Sudan, there are four treatment options available. The first two options are atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone) or artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem). These are fixed dose combination medicines that can be used for children and for atovaquone-proguanil, non-pregnant adults. The third option is Quinine sulfate plus doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin. The combination option of quinine sulfate plus either doxycycline or tetracycline is generally preferred to quinine sulfate plus clindamycin because there is a lot of data about its efficacy. Treatment with quinine should continue for 7 days for infections. The fourth option, is mefloquine, it has rare but serious side effect which is severe neuropsychiatric reactions when used at treatment doses, so it should be given only other options cannot be used [5]. The aim of this study was to assess the trend, manifestations and outcome of falciparum malaria infection in patients admitted to medical wards.

2. Methods

- Study setting: This study was conducted in Wad Medani Teaching Hospital in Gezira state, a central region in Sudan, in the period of December 2014 to May 2015, including 160 patients. The city and its surrounding areas have a tropical climate, with high rainfall and temperature varying from 20°C at night to 45°C during day times. Gezira irrigation scheme lies in Gezira state. The warm and climate of Wad-Medani city and its surrounding areas provide an ideal environment for the breeding of mosquitoes and malaria transmission. Thus, this area harbours high vector density and has high incidences of malaria. Wad-Medani teaching hospital is the largest hospital in Gezira state with bed capacity of 369. Medical wards consist of 162 beds. Bed occupancy in medical wards is 100% with estimated average length of stay, 5 days. Study design It is a descriptive, prospective, cross sectional hospital-based study. Study population:This hospital based cross sectional study was done on 160 adult patients confirmed cases of falciparum malaria (either by peripheral blood smear or rapid diagnostic test), admitted in Wad-Medani teaching hospital during the period of December 2014 to May 2015. Study tools and data collection:The information of the patients was collected from the medical records of patients admitted in medical wards with the diagnosis of malaria (positive blood film for plasmodium falciparum). A structured questionnaire consisting of data of interest domains was filled. The collected data included information on the demographic, clinical data and blood samples were taken from all patients for peripheral blood smear (thick and thin blood film for malaria), complete blood count, renal and liver function test, blood sugar and bleeding profile.Statistical analysisStatistical analysis of data was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program.Ethical considerations:A written approval was provided from the ethic committee in Wad-Medani teaching hospital as well as a written consent from all participants in the study.

3. Results

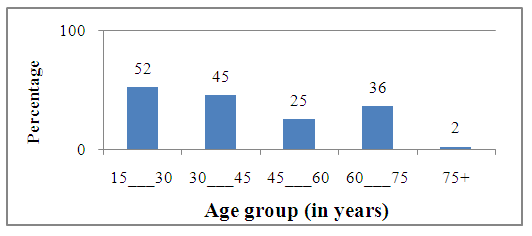

- A total of 160 patients were admitted with severe malaria during period of December 2014 to May 2015. The age of study populations ranged between 15 - 80 years, with mean age (43.11), with the most affected patients in the age group 15 - 45 years around 32.5% of patients. as shown in figure 1. Males were, 86 (53.8%) and females were, 74 (46.3%).

| Figure 1. Distribution of patients according to age |

|

|

|

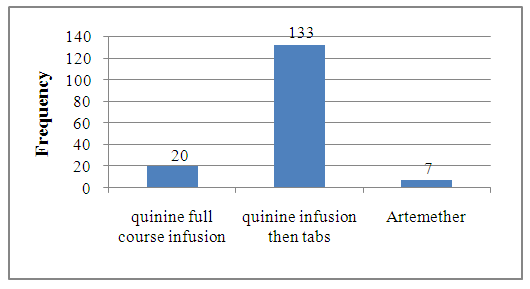

| Figure 2. Treatment of P. falciparum in the study group |

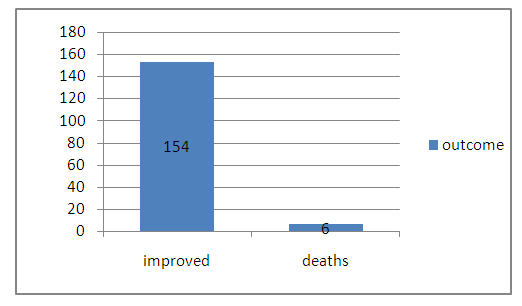

| Figure 3. Outcome of patients with malaria in the study population |

4. Discussion

- This prospective study conducted in Wad-Medani teaching hospital in Sudan, included 160 patients who were admitted in medical wards with severe malaria during the study period. The age of study populations ranged between 15 - 80 years, with mean age of 43.11 year, with the most affected patients in the age group 15 - 45 years around 32.5% of patient, in comparison to the study which was done in in a tertiary care hospital of India in 2016, by Saya RP et al, where they found that, 63% of cases were in the age group of 15-30 years and the mean age was found to be 29.51 years [6]. 53.8% of patients were males and 46.3% were females. The high number of affected age group 0f 15-45 years and male affected more than female can be explained by the fact that, these young adults and males stay outdoors until late evenings, without protective measures against mosquitos, besides that, during night time the mosquito-feeding activity is high so they will be prone to mosquito bite. It was found that, the main clinical presentation and complications of severe falciparum malaria were: hyperparasitemia which was present in 56.3% of patients, followed by hypotension or circulatory collapse in 32.5% of patients, hyperpyrexia was seen in 21.9% of patients, prostration and weakness seen in 30.6% of patients, in comparison to the above study conducted by Saya et al in India, the clinical presentations included, nausea and vomiting (35, 35%), jaundice (34, 34%), oliguria (24, 24%), altered sensorium (24, 24%), breathing difficulty (10, 10%), and seizures (5, 5%) [6], while in this study, repeated convulsions ≥ 3 times, occurred in 8.8% of patients. In a study carried out by Wasnik P et al about the clinical profile of falciparum malaria in a tertiary referral centre in Central India in 2012, they found that, fever was the most common symptom followed by impaired consciousness, other clinical manifestations of P. falciparum malaria in the same study included, anemia in 52 (65%) patients, and out of these, 5 (6.25%) patients had severe anemia and thrombocytopenia was found in 57.5% of patients. Abnormal kidney function tests were observed in 32.5% of patients [7]. In this study, complications of severe P. falciparum malaria were seen in 65% of patients as per WHO definition of severe falciparum malaria, compared to 46.25% of patients who were found to have severe P. falciparum malaria in the above study done by Wasnik et al in India [7]. In this study the complications of severe falciparum malaria included, cerebral malaria with loss of consciousness seen in 11.9% of patients. This finding was nearly similar to the findings of a study conducted in India by Ahmad et al in 2016, where they found that, cerebral malaria due to P. falciparum occurred in 7.4% of patients. (8) Another complication of severe P. falciparum in this study was, acute kidney injury (AKI) and was seen in 11.3% of patients. Severe malaria is mainly due to Plasmodium falciparum in highly endemic areas. Cerebral malaria and acute renal failure are criteria of malaria severity as defined by WHO and mainly due to P. falciparum infection. Cerebral malaria and AKI are serious complications of severe malaria. The exact direct causes of cerebral and kidney dysfunction are incompletely understood, but common pathophysiological pathways include impaired microcirculation, due to sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes, systemic inflammatory responses, and endothelial activation. Early diagnosis of malaria and prompt early treatment with parenteral antimalarial therapy will decrease the mortality of these life threating conditions [9]. Tubular necrosis due to renal vascular obstruction by parasitized erythrocytes is the primary mechanism of renal failure, but other conditions associated with severe malaria like haemolytic uremic syndrome, and hemoglobinuric nephropathy could be possible causes of renal failure in malaria. The outcome depends on early diagnosis and proper early treatment [10]. Other manifestations of complicated P. falciparum mlaria in this study were hypoglycaemia which was seen in 11.3% of patients, severe anemia (Hb ≤ 5 g/dl) abnormal bleeding, and hyperbilirubinemia as well, occurred in 6.3% of patients. Pulmonary oedema and disseminate intravascular coagulation (DIC) were detected in 1.3% of patients, and blackwater fever was diagnosed in one patient (0.6%). Hypoglycemia is a common feature of severe malaria and it may be caused by quinine- or quinidine-induced hyperinsulinemia, but it may be found also in patients with normal insulin levels. Blackwater fever is a complication of severe malaria infection, it consists febrile intra-vascular haemolysis with severe anaemia and intermittent passage of dark-red to black colour urine, its pathogenesis is incompletely understood [11]. The complications of severe malaria in the study done by Saya et al in India in 2016, where found to be as follows: renal failure (28%), shock (9%), hypoglycemia (3%), and severe anemia (1%) [6]. In the study conducted by Wasnik et al in India, in 2012, complications of severe malaria were listed as, impaired consciousness or unarousable coma, clinical jaundice in addition to, severe renal impairment, severe anemia, and circulatory collapse [7]. Other manifestations of complications 0f P. falciparum malaria infection, like acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and acidosis were not reported in this study. This was unlike the above study by Saya where acute respiratory distress Syndrome was found in 7% of patients [6]. Wasnik etal study reported ARDS as a complication of severe malaria [7]. as well as the findings in the meta-analysis study done by Val F et al in 2017, where they found the prevalence of ARDS in severe malaria caused by P. vivax was 2.2% adult with nearly 50% mortality [12]. According to WHO there are certain laboratory criteria for diagnosis of severe malaria, these include, hyperparasitemia, jaundice, severe anemia, hypoglycaemia, renal impairment and metabolic acidosis [13]. In this study the laboratory results which meet WHO criteria for severe malaria were as follows: hyperparasitemia which was present in 90 patients (56.3%), low Hb ≤ 5 g/dl was detected in 6.3% 0f patients, serum bilirubin >2.5 in 6.3% of patients’ high blood urea > 80mg/dl in 15.6% of patients, serum creatinine > 3mg/dl in 11.3% of patients, and blood sugar < 40 mg was found in 10.6%. of patients. Another laboratory finding in this study was thrombocytopenia, (platelets < 100) was found in 20.6% of patients. Thrombocytopenia is common in P. falciparum and P. vivax malaria, but it does not correlate with the severity of the infection. [13]. In this study, patients who received quinine hydrochloride salt via intravenous infusion were 153 (95.6%), and who received artemether injection were 7(4.4%). Some patients received supportive management according to their presentation. Global strategy is early diagnosis and prompt treatment of malaria and this depends on the efficacy, safety, availability, affordability and acceptability of antimalarial drugs. The effective antimalarial therapy reduces the mortality and morbidity of malaria, as well as the risk of resistance to antimalarial drugs. Quinine is a schizonticidal drug, it is used for management of severe falciparum malaria in areas with known resistance to chloroquine (like Sudan). Quinine is a potentially toxic drug. [13]. Artemether is artemisnin derivative which can also be used for treatment of severe P. falciparum malaria. Meta analysis of mortality in trials indicated that a patient treated with artemether had at least an equal chance of survival as a patient treated with quinine [13]. The main duration of hospital stay was 3-5 days in 87 (54.4%), in this study. The outcome was as follows: 96.3% of patients improved and discharged in a good condition, and six patients (3.8%) died. Compared to the study carried out by Saya in India, the mortality rate in this study is less, where, in Saya study, 18% of patients died [6]. A mortality rate of 6.25% (higher than the mortality rate in this study), was found in the study done by Wasnik PN et al in central India [7], while in the study conducted by Sarkar J et al in India 9.8% of patients with severe malaria died [14]. There has been huge decline in malaria cases as well as deaths from malaria, in the past ten years. Based on World Malaria Report, there has been a 22% reduction in malaria cases between 2010 and 2017 and decrease in malaria deaths ranging from 10% in the Eastern Mediterranean through 40% in Africa to 54% in South-East Asia. WHO recommendations for treatment of severe malaria is use of injectable artesunate, if it is not available either parenteral artemether or quinine are recommended and after three doses of parental therapy a full course of oral artemisinin-based combination therapy or quinine to complete the treatment of severe malaria [15].

5. Limits

- The linitation of this study, is that, the number of patients was small compared to real incidence of malaria in Gezira area. In addtion the study was done 4 years ago and may the manfestions of falciparum falciparumis different now, putting in mind that the enviromental situations in Sudan after the heavy rainy seasons over the past two years may getting wworse and this will make mosquitoes eradication difficult leadong to increase malaria cases with severe manifestations.

6. Conclusions

- Falciparum malaria is more common among younger adult age group and males. The main manifestations and complications of severe falciparum malaria infection in this study, were hyperparasitemia, hypotension, hyperpyrexia, prostration and weakness, cerebral malaria, AKI then hypoglycemia and repeated convulsions, and severe anemia. Most of the patients treated with quinine with very good response, and the mortality rate was 3.8%.

7. Recommendations

- Early diagnosis, anticipation of complications, and close monitoring of vital signs to pick up features of complications is essential. Initiation of early effective malaria treatment to all individuals living in endemic regions is a necessity to control morbidity and mortality, but also to successfully reach elimination targets.Malaria elimination, depends on successful vector control measures and the improvement of case detection and management.Follow up National Malaria Control Programme is necessary. Support for health policy and systems research should be mobilized to strengthen the health system.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML