-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2019; 8(2): 29-40

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20190802.01

Predictors of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Primary School Teachers in Machakos County, Kenya

Ndawa Ancent Ndonye1, Nyamari Jackim Matara1, Ireri Anthony Muriithi2

1Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

2Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Ndawa Ancent Ndonye, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Musculoskeletal disorders refer to a broad range degenerative and inflammatory conditions that affect the joints, muscles, ligaments, tendons, bones, nerves, and the localized blood circulation systems. Despite there being significant literature about musculoskeletal disorders among teachers in other parts of the world, Kenya lags behind in research. The current studies point out to high workloads and stress levels among primary school teachers because of an increase in the teacher-pupil ratio. The objective of this study was to explore the prevalence as well as person and work-related predictors to musculoskeletal disorders among Kenyan primary school teachers in Machakos County. Methods: This study adopted a cross-sectional design to collect data from 302 randomly selected teachers. Data was collected using a questionnaire and an observation checklist. It was analyzed using chi-square and logistic regression analysis and expressed as odds ratio. Results: The prevalence at any site of the body was 85.10% with lower back, knees, neck, and ankles being the most affected body sites at 58.60%, 57.6%, 53.3%, and 53% respectively. The least affected body part was the elbows at 25.2%. The positively associated risk factors were age, teaching for over four hours while standing, teaching for over four hours while sitting, working on a head-down posture, and lack of back support on chairs. MSDs prevented teachers from carrying their normal activities with lower back trouble topping in this respect at 23.8%. Conclusion: Generally, this study reveals that musculoskeletal disorders are very common among primary school teachers in Machakos County, Kenya. Among the recommendations is the need to regulate the number of lessons per teacher, number of pupils per class, and provide chairs and benches for teachers among others.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal disorders, Risk factors, Prevalence, Pain/discomfort, Health, Teachers, Sitting, Standing, Postures

Cite this paper: Ndawa Ancent Ndonye, Nyamari Jackim Matara, Ireri Anthony Muriithi, Predictors of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Primary School Teachers in Machakos County, Kenya, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 8 No. 2, 2019, pp. 29-40. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20190802.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Musculoskeletal disorders refer to a broad range degenerative and inflammatory conditions that affect the joints, muscles, ligaments, tendons, bones, nerves, and localized blood circulation systems, and may be attributed to or intensified by one’s immediate environment [1]. MSDs are among the most prominent reasons for decrease in work productivity because of absenteeism, sick leave, as well as early retirement from the profession [2]. The work of a teacher entails not just instructing, but preparation of lesson plans, assessing the students and participation in extracurricular activities such as games. School teachers are more likely to suffer from MSDs of the neck, upper limbs, and back because of the nature of their work. School teachers relative to other professions report very high rates of musculoskeletal disorders; between 40 and 95% [1]. MSDs result into major losses through missed workdays, financial losses due to medical costs, and poor work ethics related to discomfort while at work. The costs associated to MSDS range between 13 and 54 billion US Dollars per year [3].The Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA), 2007 provides for “the safety, health, and welfare of persons lawfully present at workplaces [4].” As per the Act, the occupier should carry out the necessary risk assessments regarding the safety of workers, and come up with preventive measures. In the Kenyan context, The Kenya National Union of Teachers and Kenya Union of Post Primary Teachers have been vocal in advocating for better work environment for teachers. The 2011 UNESCO report on improving the conditions of teachers in rural areas reveals that teachers experience infrastructural challenges in trying to instruct students/pupils. Such challenges can subject them to higher risk of developing musculoskeletal disorders [5]. Despite there being significant literature about musculoskeletal disorders among teachers and other workers in other parts of the world, little has been done in Kenya [6, 7]. There have however been numerous local studies exploring musculoskeletal disorders among nurses, revealing prevalence rates of over 70%. In as much as there may have been no studies exploring MSDs among teachers in Kenya, and Machakos County in particular, there have been numerous studies revealing predominance of factors that would be termed predictors of MSDs [8-10]. In Machakos County, the introduction of Free Primary Education resulted into an increase in the teacher student ratio from 46:1 in 2001 to 52:1 in 2011 [11]. The predominance of these risk factors, clearly associated with musculoskeletal disorders among teachers, alongside high prevalence in related groups made it essential to conduct a study to explore musculoskeletal disorders among primary school teachers in Machakos County.

2. Methods

- A cross-sectional study was conducted in Machakos County, Kenya between May and July 2018.

2.1. The Participants

- The study population was public primary school teachers in Machakos County. The total number of primary school teachers in Machakos county was 9,136 [12]. Yamane’s formula was used to arrive at a sample size of 384 [13]. Stratified random sampling was used to select the sub-counties to conduct the study. Stratified random sampling was used to ensure that urban, peri-urban and rual subcounties were included for the sake of inclusiveness. These sub-counties were Machakos, Matungulu, and Mwala. To ensure equal representation, proportionate sampling was used to determine the number of teachers from each sub-county to participate in the study. Simple random sampling was then be used to select the schools in which the study was conducted, in randomly selected divisions and zones. Proportionate sampling was used to determine the number of teachers per school who took part in the study. Simple random sampling was then be used arrive at the specific teachers in the schools to administer the study to. To be included in this study the participants had to have work experience of more than one year, be actively involved in teaching, and consenting to take part in the study. Teachers with a history of fractures, working part time, and with history of symptoms related to falls and road accidents, and conditions such as pregnancy were excluded from the study.

2.2. Research Instruments

- This study majorly relied on a self-administered questionnaire. Most of its parts were adopted from the Standardized Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire [14, 15]. The questionnaire bore the following sections: Demographic factors, risk factors, and prevalence of MSDs. The respondents were expected to pick the most appropriate choice, as the answers were closed-ended. An observation checklist was constructed based on literature on conditions that would predispose teachers to MSDs.

2.3. Data Analysis

- The collected information was analyzed using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize socio-demographic variables, and the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders. For hypothesis one, “Person-related factors are not associated with the prevalence musculoskeletal disorders among primary school teachers in Machakos County, Kenya,” Chi-squared test and logistic regression were used. For hypothesis two, “Work-related factors are not associated with the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among primary school teachers in Machakos County, Kenya,” Chi-squared test and logistic regression were used. Chi-square was initially done to determine the statistical associations between the independent and dependent study variables. The independent variables with significant associations with the dependent variables were then evaluated through logistical regression, and then expressed using Odds Ratios with a confidence level of 95%.

2.4. Ethical and Logistical Considerations

- Ethical approval from Kenyatta University Ethical Review Committee (KUERC); reference number PKU/760/1828. The researcher sought written informed consent from each participant. The participants were made aware of the type of study, and the risks and benefits that would accrue. They were also informed about their right to abandon the study at any point in case of any discomfort in the course of the study without any prejudice. Additionally, they were informed that all the information they gave would be handled with confidentiality, and was to be used for the purpose of the study only. The participants had the right to not respond to questions that would create any discomfort. The study was done in safe environments for the sake of the respondents. The results participants were assured that the results would be shared with them upon the completion of the study. To undertake the study, authorization was granted by Kenyatta University Graduate School, NACOSTI, Ministry of Education, County education authorities, Machakos County administration, and school head teachers. The reference number for the authorization from NACOSTI was NACOSTI/P/18/71539/21197.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

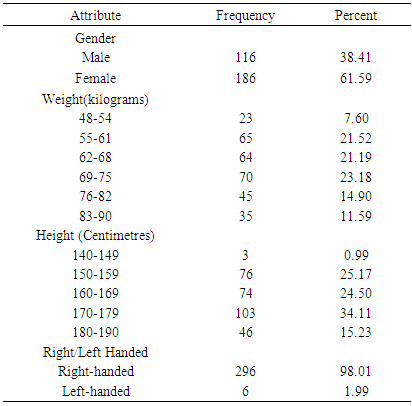

- Table 1 below presents the distribution of respondents across demographic factors. Three hundred and two questionnaires were used for analysis, a response rate of 78.56%. The results show that women made the largest proportion of the respondents (61.59%).

|

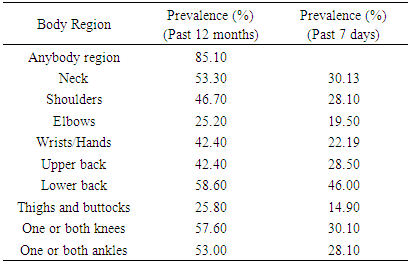

3.2. MSD Prevalence

- Table two presents the 12-month and 7-day prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among primary school teachers. The results show that the prevalence for any body part was 85.10%. The body parts that were most affected included the lower back, knees, neck and ankles.

|

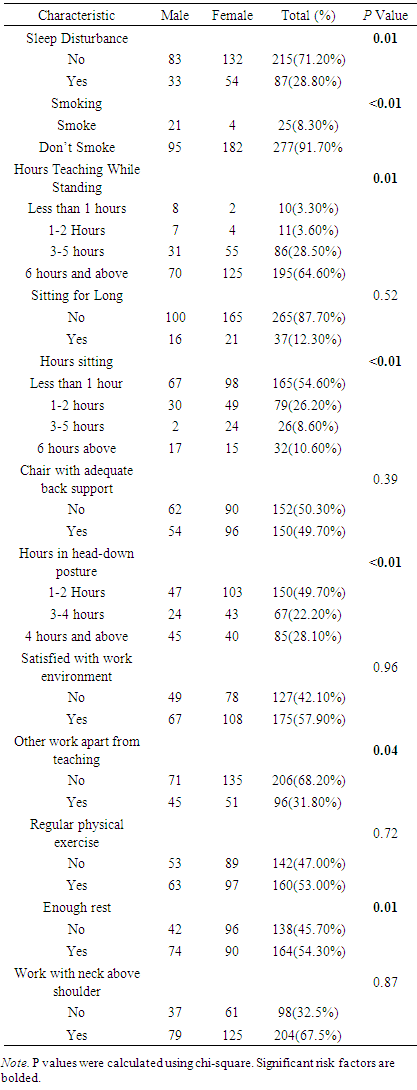

3.3. Risk Factors

- Table 3 shows the distribution of risk factors across gender. From the results, 28.80% of the respondents had experienced sleep disturbance. Regarding smoking, 8.30% were smokers. As regards hours taught while standing with 64.60% of the responded clocked 6 or more hours, 28.50% 3 to 5 hours, 3.60% for 1to 2 hours, and 3.40% for less than hour. As regards sitting for long, 87.70% did not sit for long at work while 12.30% sat for long. With respect to provision of chairs with adequate back support, 50.30% claimed that their seats did not have adequate support. Teaching on a head-down posture was also a variable of concern, and the findings revealed 61.30% worked on a head-down posture. Upon inquiry into satisfaction with work environment, 57.90% were satisfied with their work environment while 42.10% were not.

|

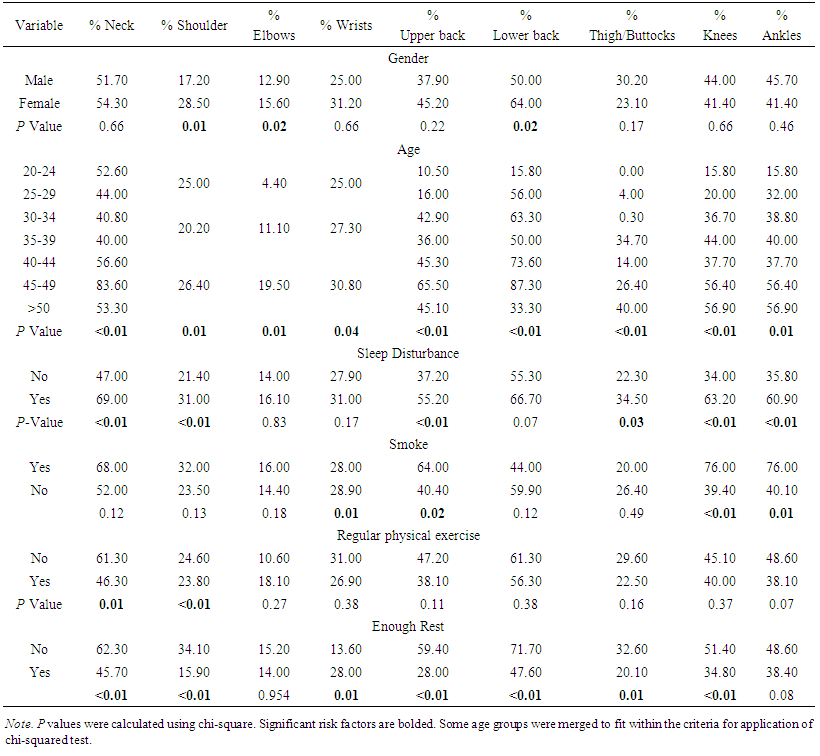

3.4. Relationship between Person-Related Factors and Prevalence of MSDs

- Table 4 shows the prevalence in respect to specific body parts in respect to personal factors. To paint a picture of the relationship between risk factors and the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders across different body parts, a chi-squared test of association was done. From the results, the prevalence of different forms of MSDs was higher among the female teachers for Neck, shoulder, elbows, wrists, upper back, lower back, and knees. The prevalence among male teachers was only higher for MSDs affecting the ankles. The difference was significant for shoulders, elbows, and lower back with p values <0.01, 0.02, and 0.02 respectively.

| Table 4. Prevalence in various regions across personal factors |

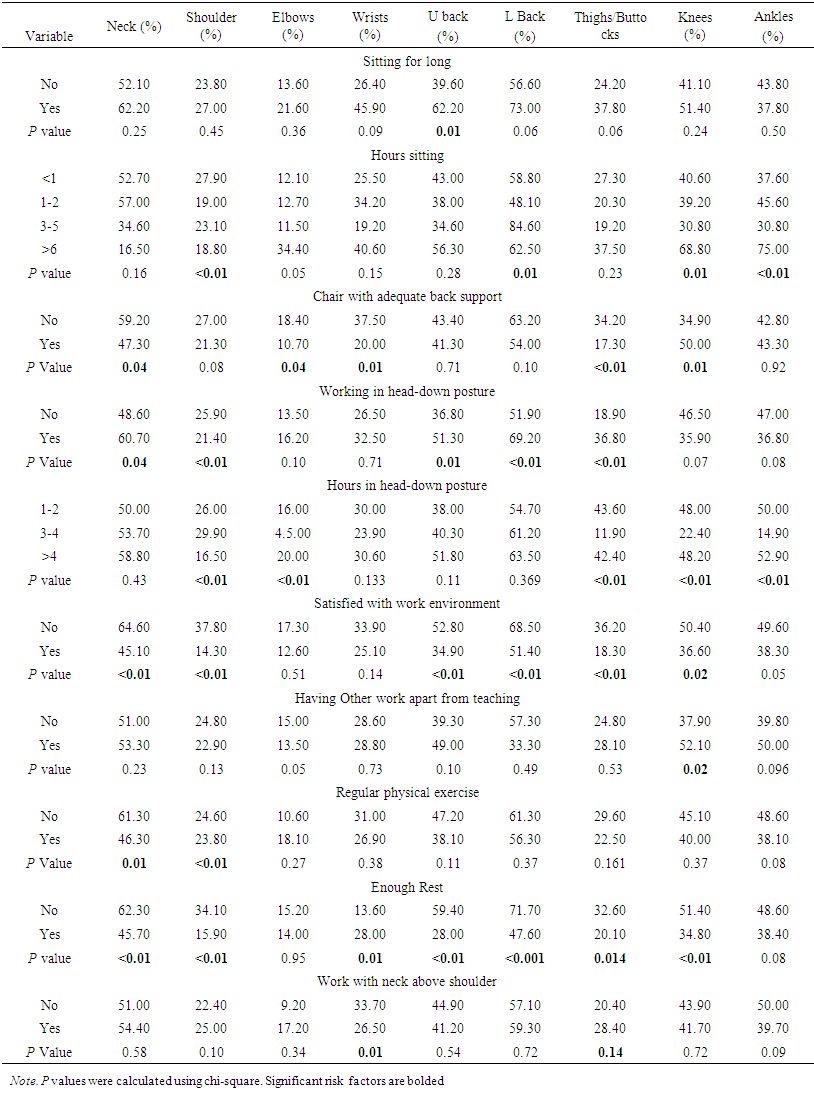

3.5. Relationship between Work-Related Factors and Prevalence of MSDs

- Table 5 shows the prevalence of MSDs across body regions in relation to work-related factors. The results show that there was higher prevalence for MSDs affecting shoulders, ankles, wrists, upper back, knees and ankles among teachers who taught between while standing for between 1 and 2 hours. The differences were significant across all the groups except for lower back (p=0.72), and ankles (p=0.06).

| Table 5. Prevalence across Body Regions in Relation to Work-Related Factors |

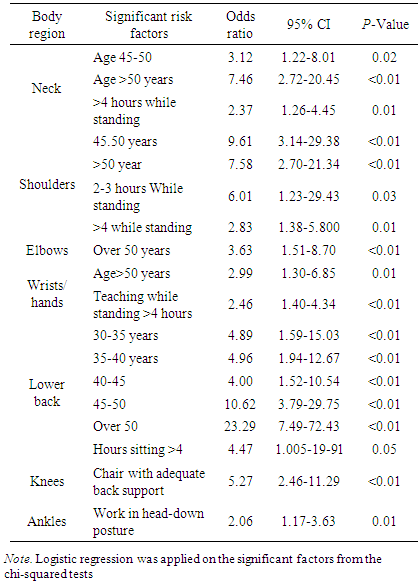

3.6. Significant Risk Factors

- Table 6 shows the factors that remained significant after the logistic regression, and expressed using odds ratios. Initial chi squared tests helped to isolate the individual factors that had significant association with the occurrence of different forms of MSDs. The independent variables that had significant associations with the occurrence of MSDs on various body parts are presented in tables four and five above. To validate the predictive power and relative contribution of the significantly associated independent variables, a logistic regression model was used. The results show that not all the variables that were initially associated with the MSDs remained significant. Age was shown to significantly predict the prevalence of neck MSDs specifically being between 45-49 years and over 50 years. The same age groups were also shown to significantly predict the occurrence of shoulder MSDs. Being over 50 years was shown to predict the prevalence of elbows and wrists/hands MSDs. Age also significantly predicted the occurrence of lower back MSDs. This was applicable to all groups except those under 30 years.

|

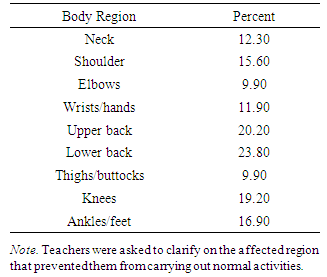

3.7. Prevention from Carrying out Normal Activities

- Table 7 shows the frequencies according to body regions as regards prevention from carrying out normal activities. Results show that upper and lower back MSDs had the highest influence in preventing teachers from carrying out their normal activities at 20.2 and 23.8 percent respectively.

|

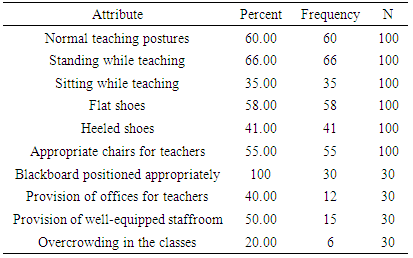

3.8. Observations Made

- Table 8 summarizes the observations that were done during the study. An observation checklist was used to gather information from selected schools and teachers. From the results, the postures made by the teachers were normal ones with no much straining observed for those who were teaching. The habits while teaching would vary depending on the teacher preferences and whether they taught lower or upper primary. Teachers who taught lower primary classes were more likely to teach while seated compared to those taught upper primary. This could be explained by the fact that most upper primary school teachers had to move to the staffroom and to other classes for other lessons. The shoe type varied based on gender with female teachers generally wearing heeled shoes and males wearing flat though there were female teachers particularly in the schools in the rural areas who wore flat shoes.

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of MSDs

- This study aimed at establishing the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among teachers in Machakos County, Kenya over the past 12 months. This prevalence, though a bit higher was within the range that had been reported among nurses in Kenya (74.20% and 70.8% [6, 7]. The overall prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders was 85.10%. This prevalence was almost similar to the ones reported in previous studies among teachers in Botswana (83.3%) [16], Chiquisaca, Bolivia (86%) [17], and 76% [18] and 72% [19] in China. This prevalence falls within the range of between 40 and 95% reported by [1] in their systematic review of literature on MSDs in the teaching profession. The prevalence was higher than that reported among teachers in Brazil (55%) [20] and in Ethiopia (53.8%) [21]. These results revealed that MSD was a significant issue among kenyan teachers, with rates that are beyond those reported across the world. The differences may be a factor of methodology, for instance the choice of sample size to involve. The most affected body parts in this study were lower back and knees at 58.60% and 57.60% respectively. The prevalence of low back pain was equal to that reported among teachers in Ethiopia (53.80%) [21], 40.40% among teachers in India [22] and 41.00% among teachers in Cairo [23]. This rate was higher than (33.10%) reported among teachers in Bolivia [17]. low back pain affected 34.9% of teachers in Nigeria [24], a considerably lower percentage compared to the one for this study. The prevalence on the knees was higher than the one found among teachers in Nigeria (34.9%) [24]. A study involving Braizilian teachers recorded a 41.00% prevalence of MSD on lower limbs which was also lower than the ones reported [20]. The rate was also higher than that recorded among teachers in Botswana [16]. The prevalence rate was also lower among teachers in Bolivia (37.5%) [17]. The prevalence was above the 22.6% reported among teachers in China [25]. Such rates for these MSDs could be a factor of the significnt risk factor revealed herein including standing for long while at work, sitting for long, and lack of back support on chairs.The second category of body parts with the highest prevalence rates was the neck and ankles. The prevalence of neck MSD was 53.30%, and was pretty close to that reported by teachers in Botswana (50.80%) [16]. The rate was equal to 57.9% reported among teachers in Enugu, Nigeria [26] and 53.52% reported among teachers in India [27]. The rate was around the 47% reported among teachers working in rural and urban areas in Bolivia [17]. The prevalence rate in relation to ankles was 30.4% among teachers in Bolivia, which is lower than that recorded in this study. The prevalence on the neck was higher than 42.0% reported among school teachers in China [19]. The prevalence on the ankles was higher than the reported (12.30%) amongst female teachers in Saudi Arabia [28] and among teacher in Botswana [16]. The third category in terms of prevalence included shoulder MSDs at 46.70%, and wrists/hands and upper back both at 42.20%. The prevalence on the shoulders was lower than the 52.5% reported among teachers in Botswana [16]. It was also lower than the rate reported among teachers in Enugu, Nigeria (62.3%) [26]. The prevalence on the shoulder was higher than the one reported among teachers in Bolivia (34.6%) [17], China (35.9%) [25], and 20.6% among female teachers in Saudi Arabia [28]. In reference to wrists, the prevalence was equal to the one reported among female teachers in Saudi Arabia (40.5%) [29]. The prevalence was higher than the one reported by teachers in Botswana (30.7%) [16]. It was also higher than the 25.7% reported among teachers in Bolivia [17]. With regards to the upper back, the prevalence was lower than the 52.6% among teachers in Botswana. It was however higher than the prevalence reported among teachers in Bolivia (35.8%) and among teachers in Saudi (17.7%) [29]. The prevalence of trouble on hands/wrists was higher than the 30.7% reported among teachers in Botswana [16], 25.7% reported among Bolivian teachers [17] 20.7% among Chinese teachers [25], and 25.2% that was reported by teachers in Northern and Eastern India [27]. It was less than the prevalence that was reported by female teachers in Saudi Arabia (59.5%) [29]. The least affected body parts on the basis of the 12-month prevalence were elbows and thighs/buttocks at 25.20% and 25.80% respectively. The prevalence of elbow trouble was higher than 12.3% reported among primary school teachers in China [25], 10% reported among Saudi’s female secondary school teachers [26], 13.3% among teachers in Botswana and 12.3% among teachers in Bolivia. This rate was also higher than the eight percent that was recorded in respect to elbows among Turkish teachers. It was also lower than 42% reported among female teachers in Saudi Arabia [30]. With respect to thighs/buttocks, the prevalence was lower than the one reported by teachers in Bolivia (31.9%) [17] and higher than the one that was reported among teachers in Botswana (18.3%). Thighs and elbows were the body parts with the lowest percentage of MSDs, a finding that was consistent with the one by Eric and Smith [16] though the rates for this study were a bit higher.

4.2. MSD Significant Risk Factors

4.2.1. Age

- From the findings of this study, increase in age had a positive relationship with neck MSDS with teachers between 45-49 years and over 50 years. Increasing age was also positively associated with shoulder trouble. The positive association also applied to MSDs affecting the elbows. Age remained positively associated with MSDs affecting wrists/hands. There was also a positive relationship between age and lower back trouble for the age groups 30-34 years, 35-49 years, 40-44 years, 45-49 years, and over 50 years. These findings are in line with those of Erick and Smith’s study among teachers in Botswana [16] that revealed that teachers teachers between 41 and 50 years and above 50 years more more likely to have MSDs affecting their knees; 1.91 and 1.85 times respectively. The relationship also aligns with the finding by Ebtesam [23] that musculoskeletal pain was associated with age (p=0.01). Cardoso et al., also converge with the findings as regards age having noted an increase in musculoskeletal pain with age [20]. In this study, with adjustments for age, the association between time that teachers had worked and musculoskeletal pain remained significant lower limbs (p<0.05), upper limbs (p<0.01) and for back (p<0.01). In a study involving Saudi teachers, age was listed among factors that has significant relationships (p<0.01) [28]. It was stated that musculoskeletal disorders were likely to increase with advancing age. In a study seeking to determine the prevalence of NSP and LBP, Eggers, Pillay, and Govender failed to establish the significance even after clearly elevated prevalence for age groups 46 to 50 and 40 to 49 years [31]. Their argument was that the small sample size could have limited the statistical power, affecting such a comparison. This relationship can be explained by the wear and tear as a consequence of aging. It can also be a factor of the organization of work as well as the work environment. Older teachers are less likely to engage in physical exercises that may help reduce the risk.

4.2.2. Hours Taught while Standing

- MSDs of the neck, shoulder and wrists were significantly associated with teaching for more than 4 hours while standing. This finding was in line with the one by Yue et al. that prolonged standing was a risk factor to lower back pain (OR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1-25-2.84) and shoulder and neck pain (OR: 2.23, 95% CI: 1.48-3.78) [18]. This trend was also consistent with a study among teaching staff in a Nigerian teaching and referral hospital where the staff who taught while standing were 1.10 times more likely to develop lower back trouble [32]. There was also a link between MSD prevalence and job duration (p<0.01) among teachers in Egypt [23]. Eggers, Pillay, and Govender also found out that prolonged standing was associated with increase in prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders (p<0.01) [31]. On the other hand, in the study involving teachers in Botswana, there was no association between the hours taught per week and the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders [16]. The exertion on the rest of the body while standing can explain the prominence of this predictor. One is likely to experience pain or other discomfort on other parts of the body following extended periods of standing. Teachers do spend loads of their times standing while carrying out tasks such as supervision and ensuring that workers have complete understanding of the concepts.

4.2.3. Hours Sitting

- Teachers who taught while sitting for over four hours in a day were 4.47 times more likely to develop MSDs affecting the lower back. This finding was congruent with the findings in [19, 21, 32]. Prolonged sitting was associated with higher occurrence of neck and shoulder trouble (OR: 1.70 95% CI: 1.36-2.34) and lower back pain (OR: 1.60 95% CI: 1.22-2.10) [19]. Beyen et al. associated prolonged sitting with 0.61 odds of developing lower back pain [21]. Erick and Smith also mentioned the relationship between sitting for long and development in their literature review [1, 2]. Prolonged sitting was ranked as the second most pronounced contributor to the development of back pain among teachers (25.20%) [22]. A study exploring job satisfaction and work tasks as predictors of LBP among teachers in Putrajaya isolated sitting for long as a significant predictor (p=0.02) [33]. On the other hand, Eggers et al. found no significant association between sitting for long and the development of musculoskeletal disorders (p=0.74) [31]. Extended hours of prolonged sitting may be explained by the fact that some tasks such as marking can only be comfortably done while sitting. The risk of MSDs is further elevated when teachers are not provided with comfortable chairs and have to strain during the tasks. This straining ends up reflecting on the lower back as the teachers have to either strecth or sit awkwardly while performing their tasks in this posture. Sitting, if done within the acceptable limits does not increase the risks of MSDs, but when prolonged becomes a significant risk factor. It is important to provide chairs with adequate back support in order to reduce the risk of MSDs following prolonged sitting.

4.2.4. Chair with Adequate Back Support

- The lack of back support on chairs was positively associated with the development of musculoskeletal issues affecting the knees. This finding was in line with the one made among teacher in China that chairs with inadequate back support were significant predictors of musculoskeletal disorder affecting the neck and shoulder (OR: 1.77, 1.23-2.55) and lower back pain (OR 1.62, 1.13-2.32) [19]. Lack of back support may result into muscle loading that can induce the development of some musculoskeletal disorders. Maintaining extreme postures in absence of the vital support can result into pain and discomfort associated with musculoskeletal disorders. The link with knees in this case can be explained by the fact that such a provision means that static loads shift to the lower body parts such as knees. Without the essential back support, one may have to use their knees for bracing, predicting the likelihood of knee problems.

4.2.5. Working on a Head-Down Posture

- Teachers who worked on a head-down posture 2.06 more likely to develop problems on their ankles. These findings are in line with Yue et al. and Ganiyu et al [19, 32]. Prolonged static postures were strongly associated with neck and shoulder trouble (OR 2.25, 1.56-3.24, 95% CI) and hand/wrist trouble (OR 2.33, 1.46-3.71, 95% CI), and knee trouble (OR 2.14, 1.36 - 3.37, 95% CI) [19]. Awkward postures ranked among the most common hazards among student participants, with p<0.01 for working or reaching away from the body [32]. The possible explanation for this trend could be the fact that working on a head-down posture particularly on poor work conditions is likely to result into exertion on the lower extremities such as the ankles. With most of the schools not furnishing the teachers adequately in terms of chair and desks in Machakos, it is not surprise that most teachers ended up working in this posture and reporting musculoskeletal disorders. Though not supported by this study, teachers working in this posture were also likely to develop neck trouble [1]. There was no signficant statistical differences with respect to working on a bend posture for long, working on a twisted posture, and working in generally uncomfortable postures according to [31]. The possible explanation for this difference could be the small sample size that was involved in this study.

4.3. Prevention from Carrying out Normal Activities

- The insight into whether musculoskeletal disorders prevented teachers from carrying normal activities during the past 12 months revealed that low back trouble was the top form in that respect as reported by 23.8% of the respondents. It was closely followed by upper back and knee trouble. MSDs of the back were also recorded among the top forms of MSDs that had prevented teachers from carrying out their normal activities [16]. On the other hand [28] reported that teachers missed 1.76±2.2 days because of trouble associated with musculoskeletal disorders. Prevention from carrying normal activities may have taken numerous shapes such as entirely failing to report to work or being present at the workplace but unable to deliver as expected.

5. Conclusions

- This was the first study in Kenya that sought to establish the prevalence and risk factors to MSDs among teachers in Kenya. The first objective was to determine the prevalence of different forms of MSDs among primary school teachers. The study revealed that musculoskeletal disorders were very common among primary school teachers. The most affected body parts were the lower back, knees, and the neck. The least common form of MSD in respect to body parts was the elbow MSD. It was revealed that MSDs had prevented a considerable number of teachers from carrying out their normal activities in the past 12 months. Lower back trouble was the most common form of MSD that prevented teachers from carrying out their normal activities. The second objective was to determine the person related predictors of existence of musculoskeletal disorders among teachers in Machakos County, Kenya. The person-related predictor that stood significantly was age with prevalence increasing with increase in age. The third objective sought to determine work-related predictors of musculoskeletal disorders among teachers in Machakos County, Kenya. In line with this objective, The odds of MSDs increased with increase in hours taught while standing, hours taught while sitting, lack of back support on chairs, and working on a head-down posture.

6. Recommendations

- The high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders alongside isolation of specific sigificant risk factors calls for action from all the relevant stakeholders. Ÿ Policies can also be set out to limit the number of lessons that teachers can be assigned in order to reduce instance of overworking and subsequent development of musculoskeletal disorders. Ÿ Policies can also be laid out to govern the number of pupils per class to reduce the risk of overworking among teachers. Ÿ The ministry of education would need increase funding to ensure that all teachers are provided with an adequate number of appropriate chairs in the classes, staffrooms, and offices. Ÿ With teachers who sit or stand for long being the most affected with MSDs, it would be important to recruit more teachers to ease their workload. Ÿ Teachers can also be trained about how to avoid MSDs. The county and national governments would also need to work together to ensure that all schools are given equal infrastructural support, especially on the basis of the finding that schools near town centers had better infrastructure. Ÿ The teachers can on their part engage in activities such as physical exercise to reduce the risk of MSD. They can also avoid working in postures that can put them at increased risk of musculokeletal disorders.

7. Further Research

- With this study having adopted a cross-sectional design, a longitudinal study would be ideal to help understand the development of conditions among teachers. Comparative studies can also be welcome to isolate the variations between rural and urban schools based on the great variations revealed between schools that were in urban and rural areas in terms of provisions for the teachers. A comparative study between public and private schools to compare the rates of MSDs between public and private schools or primary and secondary schools would also be welcome. It would also be important to explore the preventive role of physical exercise on the occurrence of work related MSDs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Sincere gratitude to the study participants for their contribution and to the supervisors for their unwavering support. Availability of Data and materials The analyzed datasets can be provided upon reasonable request.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML