-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2019; 8(1): 8-20

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20190801.02

Enhancing Male Partners’ Involvement in the Elimination of Mother-To-Child Transmission (EMTCT) of HIV in Zambia

Jean Bosco Nzitunga

Administration and Operations, International Criminal Court (ICC), Bangui Field Office, Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR)

Correspondence to: Jean Bosco Nzitunga, Administration and Operations, International Criminal Court (ICC), Bangui Field Office, Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR).

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The global community has committed itself to eliminating mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV as a public health priority. Male participation in the elimination of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT) of HIV has been determined as one of the key factors in sub-Saharan African countries, but its realization is challenging because of male-related and institutional factors. In Zambia, most of the research on the EMTCT of HIV have focused on the role of women and have ignored male partners’ role in this regard. A careful investigation revealed a dearth of literature in this regard, which led to the following research question: what is the influence of knowledge and educational campaigns/programs on male partners’ propensity to support the EMTCT of HIV programmes?” To address this question, a quantitative survey design was used. The population for this study comprised men living at the George Compound in Lusaka. A sample of 110 men were selected using purposive sampling approach and a 6-point Likert scale questionnaire was administered to them. The response rate was 91%. The findings indicated a positive influence of knowledge and educational campaigns/programs on male partners’ propensity to support EMTCT of HIV programmes.

Keywords: Male partners, Involvement, Mother-To-Child, EMTCT, HIV

Cite this paper: Jean Bosco Nzitunga, Enhancing Male Partners’ Involvement in the Elimination of Mother-To-Child Transmission (EMTCT) of HIV in Zambia, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 8-20. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20190801.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The transmission of HIV from an HIV-positive mother to her child during pregnancy, delivering or breast feeding is called mother-to-child transmission (WHO, 2010, p.1). Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV is an important contributor to HIV transmission. It remains the most prevalent source of paediatric HIV infection. In 2010 alone, an estimated 390,000 children were infected with HIV, 90% of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS, 2011, p.3). Paediatric HIV threatens to reverse gains made in controlling child mortality in African countries with high HIV sero-prevalence. Aside the dominant hetero-sexual transmission of HIV, vertical transmission from mother to child accounts for more than 90% of paediatric HIV/AIDS (WHO, 2010, p.3). HIV infection accounts for more than 20% of child deaths in southern Africa compared with approximately 3% globally (Srikantiah, 2011, p.4).In 2012, an estimated 260 000 children were newly infected with HIV, and an estimated 3.3 million children were living with HIV (UNAIDS, 2013, p.2). MTCT of HIV occurs when an HIV-positive woman passes the virus to the baby during pregnancy, labour and delivery, or after delivery through breastfeeding. Without prophylactic treatment, approximately 15–30% of infants born to HIV-positive women will become infected with HIV during gestation and delivery, with a further 5–15% becoming infected through breastfeeding (WHO, 2013, p.4). HIV infection of infants creates a life-long chronic condition that potentially shortens life expectancy and contributes to substantial human, social, and economic costs.Primary prevention of HIV, prevention of unintended pregnancies, effective access to testing, counselling, antiretroviral therapy (ART), safe delivery practices, and appropriate infant feeding practices (including access to antiretroviral drugs to prevent HIV transmission to infants) all contribute to elimination of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT) and also reduce child mortality (WHO, 2013, p.5). This threat has been recognized by the international community, which has spurred advocacy, political and financial responses to reduce – and ultimately eliminate – MTCT. Indeed, in recent years, the number of women accessing programs that aim to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV has steadily increased (UNAIDS, 2013, p.5). Most prevention of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT) programs have concentrated monitoring and evaluation efforts on measuring process indicators such as acceptance rate of HIV testing and counseling or proportion of HIV-positive women provided with antiretroviral drugs (Srikantiah, 2011, p.5). However, there is a need to properly incorporate other potential determinants of the effectiveness of EMTCT of HIV.In Zambia, with a population of 12.9 million people, the estimated number of pregnant women in 2009 needing ART was 68,000 (WHO, 2010). Annually, more than 90% of pregnant women in Zambia utilize antenatal care (ANC) services, and the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV programme is available to those women who test HIV positive. The importance of male participation in enhancing the effectiveness of EMTCT of HIV programmes cannot be overemphasised (Kasenga, Hurtig, and Emmelin, 2010, p.28). Male participation in the EMTCT of HIV programme is needed to increase couples’ awareness of their own HIV status, to support maintaining HIV-negative status and to encourage HIV-positive mothers to commit to the programme throughout the whole maternal process. Despite considerable progress in EMTCT of HIV recorded since 2009 in Zambia, programmatic challenges remain in retaining women in care and providing them with antiretroviral medicines throughout the breastfeeding period, as the mother-to-child transmission rate of HIV rises from 3% at six weeks to 6% at the end of breastfeeding (UNAIDS, 2015, p.3).The Zambian National Programme of PMTCT of HIV has been studied from different aspects, i.e. the sufficiency of health labour for the increasing HIV workload (Walsh, Ndubani, Simbaya, Dicker, and Brugha, 2010), the efficacy of PMTCT of HIV in different age bands among perinatally-exposed children (Torpey, Kasonde, Kabaso, Weaver, Bryan, Mukonka, Bweupe, Zimba, Mwale, and Colebunders, 2010), sufficiency of funds and human resources to implement a more effective ARV regimen (Nakakeeto and Kumaranayake, 2009), the implementation of an efficacious ARV regimen among HIV-positive pregnant women and associated factors (Mandala, Torpey, Kasonde, Kabaso, Dirks, Suzuki, Thompson, Sangiwa, and Mukadi, 2009), and the infant-feeding components of a PMTCT of HIV program (Chopra, Doherty, Mehatru, and Tomlinson, 2009). However, little research has been conducted on the impact of male partners’ participation in the EMTCT of HIV programmes in the Zambian context.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Elimination of Mother-To-Child Transmission (EMTCT) of HIV

- HIV infection transmitted from an HIV-infected mother to her child during pregnancy, labour, delivery or breastfeeding is known as mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). In the absence of any interventions, transmission rates range from 15-45% (5-10 percent during pregnancy, 10-20 percent during labour and delivery, and 5-20 percent through breastfeeding). With effective interventions this rate can be reduced to less than 2% in non-breastfeeding populations, and to 5% or less in breastfeeding populations (UNICEF, WHO, UNAIDS, 2009, p.5). Effective elimination of mother-to-child transmission involves simultaneous support for several strategies that work synergistically to reduce the odds that an infant will become infected as a result of exposure to the mother’s virus. Through the reduction in overall HIV among reproductive-age women and men, the reduction of unwanted pregnancies among HIV-positive women, the provision of antiretroviral drugs to reduce the chance of infection during pregnancy and delivery and appropriate treatment, care and support to mothers living with HIV (including infant feeding), programs are able to reduce the chance that infants will become infected (UNICEF, WHO, UNAIDS, 2009, p.5).In ideal conditions, the provision of antiretroviral prophylaxis and replacement feeding can reduce transmission from an estimated 15-45% with no intervention to around 1-2% (UNAIDS, 2010, p.2). In high-income countries mother-to-child transmission has been virtually eliminated thanks to effective voluntary testing and counselling, access to antiretroviral therapy, safe delivery practices, and the widespread availability and safe use of breastmilk substitutes (UNAIDS, 2010, p.3). If these interventions were used worldwide, they could save the lives of thousands of children each year. Unfortunately, most developing countries have not yet reached all pregnant women with these services, let alone significantly reduced HIV prevalence among reproductive-age individuals or unwanted pregnancies among HIV-positive women. In 2010, around 390,000 children under 15 became infected with HIV, mainly through mother-to-child transmission (UNAIDS, 2012, p.4). About 90% of children living with HIV reside in sub-Saharan Africa where, in the context of a high child mortality rate, AIDS accounts for 8 percent of all under-five deaths in the region (UNAIDS, 2012, p.5).The EMTCT of HIV is a technically sound set of strategies that greatly improves maternal and child health (UNAIDS, 2010, p.4). This comprehensive approach includes the following three elements: the primary prevention of HIV infection among women; the prevention of unintended pregnancies among HIV infected woman; and the provision of specific interventions to reduce HIV transmission from HIV-infected mothers, their infants and family (WHO, 2007, p.5).Successful EMTCT of HIV requires a number of relevant activities to be embarked upon. For the first element (primary prevention of HIV infection among women, especially young women), key activities to be considered include health information and education, HIV testing and counselling-regular retesting for those with exposure, couple counselling and partner testing, safer sex practices, including dual protection (condom promotion), delay of onset of sexual activity and behavioural change communication to avoid high risk behaviour. Key activities to be considered in the second element (prevention of untended pregnancies among HIV-infected women) are FP counselling and services to ensure women can make informed decision about their reproductive health, HIV testing and counselling in RH/FP services and safer sex practices, including dual protection (condom promotion) (WHO, 2007, p.6).In the words of Ngubane (2012, p.1), “implementing an effective, comprehensive and integrated EMTCT programme had the potential to substantially improve adult, maternal, infant and child health outcomes through reducing new paediatric HIV infections in women and their male partners with prevention approaches targeted to their infection status, preventing unintended pregnancy among HIV-positive women, and building capacity for health systems through training of health workers, improved laboratory, data monitoring and evaluation systems.” When effectively implemented, EMTCT of HIV interventions can virtually eliminate the risk of childhood HIV infection and improve maternal survival. However, what many believed at the outset would be a relatively simple matter of incorporating antenatal HIV diagnosis and maternal-infant antiretroviral prophylaxis into routine pregnancy and new-born care has in practice been frustratingly difficult to bring to scale (Stringer, Ekouevi, Coetzee, Tih, Creek, Stinson, Giganti, Welty, Chintu, Chi, and Wilfert, 2010, p.296). To begin with, the majority of women in low and middle-income countries has never been tested for HIV and is therefore unaware of their status (WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF, 2010, p.4). This means that effective EMTCT programs must provide counselling and testing services to determine which women are in need of assistance. Beyond testing, infected women must adhere to a critical pathway – referred to as the PMTCT cascade – of events that must be in place for the prophylaxis to be delivered (Stringer, Chi, Chintu, Creek, Ekouevi, Coetzee, Tih, Boulle, Dabis, Shaffer, and Wilfert, 2008, p.58). Additionally, even after a woman is diagnosed with HIV, there is no guarantee that she will agree to ARV drug prophylaxis. Studies in Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Kenya have found that up to 40–60% of HIV-infected women decline short course ZDV prophylaxis in pregnancy once diagnosed (Stringer et al., 2010, p.297). Reasons for non-acceptance of testing or interventions certainly vary among these settings, but may be tied to poor understanding, patient denial and fear of stigma (Stringer et al., 2010, p.298).Failure of any of the multiple sequential steps of EMTCT care results in cumulative losses of pregnant mothers from EMTCT services, with increased risk of HIV transmission to their infants. A study carried out by UNICEF between January 2000 and June 2002 shows that of more than half a million women who attended clinics in twelve countries, only 71% received counselling; of those who were counselled, only 70% took an HIV test; among women who tested HIV positive, only 49% received preventive drugs (UNICEF, 2003, p.7). Similarly, a multicounty evaluation of four African countries (Cameroon, Cote’ d’Ivoire, South Africa and Zambia) examined the effectiveness of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services at both the community and facility level. The study found that of the 3,244 HIV-positive pregnant women who delivered in health centres offering PMTCT services in the four countries, 84% were offered testing, 57% adhered to maternal ARV prophylaxis and 49% adhered to infant ARV prophylaxis (Stringer et al., 2010). Yet, another study in Zambia demonstrates attrition along the PMTCT cascade (Mandala et al., 2009, p.3).

2.2. Male Participation in EMTCT of HIV

- The lack of male involvement in EMTCT deprives women of their partners care and support in coping with HIV infection, in taking antiretroviral therapy and making appropriate infant feeding choices (WHO, 2011, p.7). Limited or lack of male partner involvement in EMTCT services is one of the major impediments in scaling up and increasing population coverage of EMTCT. Over time, EMTCT of HIV campaigns have been directed at women more generally, based on an assumption that women tend to be the guardians of their families’ health. But there are limits to such strategies, as women are frequently ill-placed to ensure that prevention messages which call for a reduction in the number of sex partners or use of condoms are put into practice (Abuhay, Abebe, and Fentahun, 2014, p.339). Only recently has there been a more concerted shift towards targeting men, in recognition of the fact that they ‘drive the epidemic’ The lack of male involvement particularly affects the uptake of interventions for EMTCT because some women do not get permission to undergo HIV testing, are afraid to disclose their status to their partners or are prevented from adopting safer infant-feeding practices. Male involvement is crucial in infant feeding options, family planning and general health of both mother and child (Amano and Musa, 2016, p.2).Regardless of the male partner’s HIV status, involving him in HIV counselling and testing can help to ensure that he is supportive of his partner’s dilemma and choices related to issues like infant feeding, ARVs and family planning (Adera, Wudu, Yimam, Kidane, Woreta, and Molla, 2015, p.223). There has been very little emphasis on encouraging male partners to be involved in PMTCT despite their important roles and responsibilities. In most PMTCT programmes the uptake has been disappointingly low with many women declining to be counselled or tested for HIV (Gebru, Kassaw, Ayene, Semene, Assefa, and Hailu, 2015, p.461).Breastfeeding still remains the most feasible option for feeding infants in most resource-constrained settings with the risk of HIV transmission through breast milk ranging from 14-29%. Male involvement in infant feeding decision is crucial for the success of the intervention. Several studies have confirmed the relationship between infant feeding choices and male involvement in EMTCT. In a study looking at the effect of partner involvement and couple counselling on uptake of EMTCT interventions noted that HIV positive women receiving couple counselling were five-fold more to avoid breastfeeding compared to those counselled individually (Alemayehu, Etana, Fisseha, Haileslassie, and Yebyo, 2014, p.22).In addition, in most settings few men are aware that their partners have been tested during their antenatal care. This is because, few women share their test results with their partners with few men receiving counselling and testing with their partners. There are several barriers to male involvement in health issues particularly reproductive and maternal child health. One of it is that, despite the fact that men are the key decision makers at the family level, they are not well informed on health issues. Men are also not used to seeking services with their spouses; they instead do it on their own (WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF, 2011, p.8).Globally, male involvement has been recognized as a priority focus area to be strengthened in PMTCT. This can be accompanied by encouraging couple counselling and mutual disclosure. This will benefit adherence, improve uptake and continuation of family planning methods and provide family-centred care and treatment. Male partners who are diagnosed as being HIV positive should be given or referred to appropriate treatment and care (WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF, 2011, p.10). In gender responsive approach, involving men in HIV/AIDS programs respond to the strategic needs of women, as the goal of involving men in such programs is to transform the socio-cultural norms, gender roles, stereotypes and unequal power relationships that constrain women’s access to and uptake of programs; engage men as partners, fathers and beneficiaries in order to take into account the ways that power relations with men affect women’s access to services; make services more male-friendly; and engage male community leaders to challenge harmful gender norms (WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF, 2011, p.11).Men’s participation is one of the key factors in the EMTCT of HIV and is enhanced by their knowledge and available educational campaigns/programs which are discussed in the next section.

2.3. Knowledge and Educational Campaigns/Programs

- For the success of EMTCT of HIV programmes, it imperative to provision of adequate information to the general population and relevant service providers on the programme through well-coordinated campaigns to create awareness and positively influence attitudes, norms, values, and behaviours of the public regarding EMTCT and to improve the capacity and skills of healthcare providers for standard EMTCT services (Stringer et al., 2010, p.298). According to Busari, Olanrewaju, Desalu, Opadijo, Jimoh, Agboola, Busari, Olalekan (2010, p.88), adequate knowledge of a disease condition has been reported to influence attitude and practice of patients in the management of their illnesses, and this enhanced knowledge is known to improve compliance with interventions to prevent and/or control conditions such as MTCT of HIV. This knowledge is enhanced by adequate educational programs about EMTCT of HIV. This view is supported by several empirical studies.Omondi, Ongo’re, Ngugi and Nduati (2012) conducted about the “Quality of PMTCT Services and Uptake of ARV prophylaxis amongst HIV positive Pregnant Women” in Kakamega District of Kenya. The study was a cross-sectional study. 30 health facilities and healthcare workers were sampled using multi-stage sampling technique. From the 30 health facilities, 119 HIV-positive pregnant women were surveyed by convenience sampling. The PMTCT counsellors and HIV-positive pregnant women were interviewed using structured questionnaire. The results of the study indicated maternal ARV prophylaxis uptake was the highest among HIV pregnant women who knew about MTCT and who had been exposed to adequate educational campaigns about PMTCT of HIV. These findings imply that PMTCT campaigns created awareness and enhanced the knowledge level of HIV-positive pregnant women on the PMTCT programme which consequently led to high rate of ARV prophylaxis uptake.Hembah-Hilekaan, Swende, and Bito (2011) conducted a study on the “Knowledge, Attitudes and Barriers towards Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV among Women attending Antenatal Clinics in Uyam District of Zaki-Biam in Benue State, Nigeria.” The study was conducted from 21st March to 20th July 2011 using pretested questionnaire administered on women attending antenatal care (ANC) and postnatal mothers (those who had delivered live babies in last six weeks) in rural health centres in Uyam District of Zaki-Biam, a semi-urban area of Benue State, in North-Central Nigeria. The study found a positive relationship between the knowledge about PMTCT and participants’ support to the PMTCT programme.Olugbenga-Bello, Oladele, Adeomi, and Ajala (2012) carried out a study entitled “Perception about HIV testing among Women attending Antenatal Clinics at Primary Health Centres in Osogbo, Southwest of Nigeria.” It was a survey study conducted in Olorunda Local Government Area, one of the 30 LGAs in Osun State with administrative headquarters in Igbona, Osogbo, Nigeria. The study covered all pregnant women that attended antenatal book clinic (first ANC visit in current pregnancy) in three randomly selected primary health care centres in the local government area understudy, between May and August 2009, and a total of 270 respondents were sampled. The study found that women who had benefited from adequate information about MTCT were more involved in EMTCT of HIV initiatives.Geoffery (2011) studied the “Knowledge, Attitudes and Intended Practices of Pregnant women regarding prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT)” in Mzimba District of Malawi. It was a survey study with a sample size of 384 pregnant women selected by systematic sampling in six out of the ten health facilities offering antenatal care and VCT. The study findings indicated that knowledge and educational campaigns were positively associated to attitude towards the PMTCT programme.Balogun and Odeyemi (2010) conducted a study entitled “Knowledge and Practice of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV among traditional attendance in Lagos State, Nigeria”. Using survey research method and multi-stage sampling technique, the 108 registered TBAs in Ajeromi-Ifebdun and Mushin Local Government Areas of Lagos State were sampled. The study found amongst others that the most common source of information was from health workers 78.7%, followed by electronic media 30.6%, and other TBAs 7.4%. The study revealed a positive influence of knowledge and educational programs on the involvement in EMTCT.On the other hand, Goncho (2009) conducted a study on the factors influencing the utilization of PMTCT services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and discovered that knowledge in the community as well as among the pregnant women on transmission of HIV from mother-to-child during breastfeeding and PMTCT services was high but utilization of the services was low. The study concluded that having knowledge about PMTCT does not necessarily guarantee enhanced use of PMTCT services.All these diverse empirical research findings point to the need to investigate the existence of this relationship in the context of Zambian male partners’ participation.

3. Theoretical Framework

- Theories serve to justify the practice and practice, in turn, informs theory (Macfarlane, 2007, p.6). This study is founded on six theoretical models of behaviour change about HIV, namely the Health-Belief Model; the Reasoned Action Model; the Social-Cognitive and Information-Motivation- Behavioural Skills Models; the Stages of Behaviour Change Models; the Social Diffusion Models; and the Social/Environmental Change Model.

3.1. Health-Belief Model

- This model by Rosenstock, Strecher, and Becker (1994) attempts to explain how individuals will take action to avoid ill health. First, individuals must recognise that they are susceptible to a particular condition (‘at risk’), and must perceive that the severity of the condition is such that it is worth avoiding. They must also perceive that the benefits of avoidance are worth the effort of changing their behaviour and the possible adverse effects of the change (e.g. an alcoholic losing friends when they stop drinking). Finally, they must perceive that they have the self–efficacy (in terms of skills, assertiveness, etc.) to change their behaviour. (Self-efficacy is ‘functional self-confidence’: it is a person’s confidence that they will accomplish a specific task). Cues to action are considered important in assisting all stages of change in this model. A cue for action could be a poster, a face–to–face encounter with an outreach worker or a conversation with a friend (Rosenstock et al., 1994, p.6).In the words of Rosenstock et al. (1994, p.7), “programs to deal with a health problem should be based in part on knowledge of how many and which members of a target population feel susceptible to AIDS, believe it to constitute a serious health problem and believe that the threat could be reduced by changing their behaviour at an acceptable psychological cost.” This suggestion is supported by Gerrard, Gibbons, and Bushman (1996, p.392) who underscore that behaviour change is most likely to occur in circumstances where severity and susceptibility are rated highly by individuals.

3.2. Reasoned Action Model

- The reasoned action model by Fishbein, Middlestadt, and Hitchcock (1994) assumes that most forms of human behaviour are a matter of choice. Thus, the most immediate determinant of any given behaviour is an individual's intention about whether or not to perform that behaviour. This in turn is influenced by the degree to which the person has a positive attitude towards the behaviour, and the degree to which they expect that important others will think that they should perform the behaviour. For example, if someone is told not to do something by someone they respect, they are more likely to act on that warning, according to the reasoned action model. There are very few evaluations of interventions aiming to alter beliefs and intentions amongst people at risk of HIV infection, despite the strength of association demonstrated between intention and behaviour in such areas as smoking control, alcoholism treatment, contraceptive behaviour and weight loss (Fishbein et al., 1994, p.65).

3.3. Social-Cognitive and Information-Motivation-Behavioural Skills Models

- Bandura’s (1994) social-cognitive learning theory is a general theory of self-regulatory agency, which proposes that perceived self-efficacy lies at the centre of human behaviour. According to this model, effective self-regulation of behaviour and personal change requires that people believe in their ability to control their motivation, thoughts, affective states and behaviours. In other words, people are unlikely to change unless they want to, believe they can, feel they will and have the behavioural skills (Bandura, 1994, p.26). This model also proposes that people will require practice and feedback in order to develop self–efficacy in taking preventive action and that social supports for the desired personal changes will be essential. Bandura (1994, p.27) argues that “the major problem is not teaching people safer sex guidelines, which are easily achievable, but equipping them with skills and self–beliefs that enable them to put the guidelines into action consistently in the face of counteracting pressures.”A refinement of the social-cognitive learning theory is the information-motivation-behavioural skills model by Fisher and Fisher (2000). This is a feedback-loop model: it also assumes that the three components of information, motivation and behavioural skills exert potentiating effects on each other. To this extent, the finding by Albarracín, Gillette, Earl Glasman, Durantini and Ho (2005) that information has positive influences on behaviour only when accompanied with active, behavioural strategies can be taken as evidence that the confluence of strategies is as important as the selection of each individual approach.

3.4. Stages of Behaviour Change Models

- The behaviour-change-stage model by Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross (1992) offers an explanation of the stages through which an individual will progress during a change in health behaviour. It divides behaviour change into the following stages:Ø Pre-contemplation – lack of awareness of risk, or no intention to change risk behaviour;Ø Contemplation – beginning to consider behaviour change without commitment to do anything immediately;Ø Preparation – a definite intention to take preventive action in the near future;Ø Action – modification of behaviour, environment or cognitive experience to overcome the problem; andØ Maintenance – the stabilisation of the new behaviour and avoidance of relapse.A similar model is the AIDS Risk Reduction Model by Catania, Kegeles, and Coates (1990) which divides behavioural change into three stages, each with several influencing factors. Both theories attempt to define a sequence of stages that go from behaviour initiation to adoption to maintenance. Successful interventions should be the ones that focus on the particular stage of change the individual is experiencing and facilitate forward progression. Presumably, knowledge of HIV/AIDS or more general risk perceptions may serve to prompt change when people are not yet performing the behaviour, but may not elicit movement beyond the initial stage. Similarly, inducing favourable attitudes may be important at the very initial stages, but not when people are already performing the behaviour and are aware of its outcomes. People who have already adopted the idea of change and begun to perform the behaviour may then need new skills to foster complete success (Catania et al., 1990, p.55).This finding should give some cheer to the developers of mass-media and prevention-information campaigns. They imply that although behavioural-skills training is generally a necessary part of an effective EMTCT of HIV programme, the provision of information, although it does not effect change in itself, can prompt people to think about changing and can help them maintain safer behaviour when they have made changes.

3.5. Social Diffusion Models

- Innovations are diffused through social networks over time by well-established rules; health-related behaviours are no exception. A body of social theory called social diffusion theory by Dearing, Meyer, and Rogers (1994) has studied the diffusion of innovations in fields such as agriculture, international development and marketing. Diffusion of innovations theory has been adopted for the study of the adoption of behaviour intended to avoid HIV infection. Diffusion theorists argue that a behaviour or innovation will be adopted if it is judged to have a high degree of utility, and if it is compatible with how individuals already think and act.However, an innovation will only be considered if it is known about, and one of the major problems facing HIV educators is the difficulty of frank communication about HIV risk and how best to protect oneself and one's partners. The taboo status of much discussion about HIV makes it difficult for individuals to judge the utility of an innovation such as condom use, because frank discussion of condom use is impossible on television (Dearing et al., 1994, p.81).Diffusion research has also observed that innovations will tend to be adopted in a population according to a distribution that follows an S–shaped curve: that is, few at first, then an increasing proportion, and a few late adopters. Diffusion researchers have been very interested to define the characteristics of who adopts early, and who influences those who adopt an innovation later. They discovered that rates of adoption varied according to the homogeneity of the group, with innovations diffusing more rapidly in groups which were relatively homogenous. ‘Change agents’ who modelled a new innovation or disseminated information about it were most likely to be successful if they came from that group (Dearing et al., 1994, p.83).Two other factors cited as important in the diffusion of innovations have particular relevance to HIV prevention. ‘Testability’ – opportunities for individuals to experiment with an innovation – and ‘visibility’ – the knowledge that others are already doing it – are crucial steps in the diffusion process (Dearing et al., 1994, p.85).

3.6. Social/Environmental Change Model

- The social/environmental change model assumes that there are broad structural factors which shape or constrain the behaviour of individuals (Friedman, Des Jarlais, and Ward, 1994). Without seeking to change the root causes or structures that affect individual risk and vulnerability to HIV, individually-focused interventions will be unable to achieve real change. The model suggests that influencing social policy, the legal environment, economic structures and the medical infrastructure are some of the key routes to achieving change. This model proposes the necessity of working with social groups, not individuals, and is the theoretical underpinning for activism, advocacy and political lobbying.Friedman et al. (1994, p.97), amongst many others, have argued that it is only by reference to social factors that we can understand differences in HIV prevalence amongst different ethnic groups. Numerous studies have found that various environmental factors are associated both with high levels of risk behaviour and high levels of HIV infection. These range from:• Factors that could be influenced by economic improvement, such as the poverty that drives some women and men into sex work;• Factors that could be influenced by legislative change, such as laws which criminalise needle exchange, sex work or sex between men; and• Factors that can be influenced by cultural change or education programmes, such as stigma against people with HIV in the general population or in bodies like the police.According to Gupta, Parkhurst, Ogden, Aggleton, and Mahal (2008, p.766), an analysis of how social, political, economic and environmental factors relate to risk is the starting point for planning interventions. For example, gender inequality may be theorised to increase unprotected sex through more than one causal chain - women are economically dependent on men, so feel unable to negotiate condom use because they fear being abandoned by their partner. In addition, fear of violence by men leads to women being unable to negotiate condom use. Interventions need not aim to achieve total change with regard to gender inequality, but can identify points in a causal pathway where change may be achieved. For example, interventions may aim to help women be more economically independent, uphold women’s property rights in cases of domestic abuse, prosecute men who inflict violence or provide havens for women who have experienced violence. The social-change model is influential in setting the agenda for EMTCT of HIV and social change is regarded as essential as a prerequisite for tackling epidemics in certain populations. However, social change may not be sufficient in itself to produce a reduction MTCT incidence and may sometimes have paradoxical effects. Taking account of individual vulnerabilities and skills deficits will also continue to be an essential part EMTCT of HIV programmes.

3.7. Research Model and Hypotheses

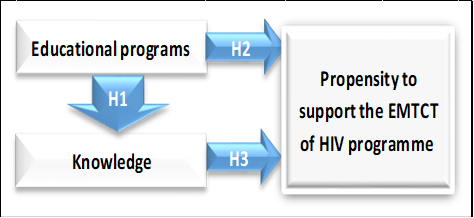

- Based on the theoretical models discussed above, the literature reviewed in Section 2, and the problem statement, this study seeks to enrich the body of knowledge in the area of EMTCT of HIV by advancing and analysing a model which postulates educational programs and knowledge as determinants of male partners’ propensity to support the EMTCT of HIV programme. The research model is presented in Figure 3.1.

| Figure 3.1. Research Model (adapted from Nzitunga, 2015) |

4. Methodology

- For this study, a quantitative approach was used. Measurable data were used to formulate facts and uncover patterns in research. The population for this study comprised men living at the George Compound in Lusaka. Living at the George Compound in Lusaka was the first inclusion criterion. The other criteria were that the participant’s wife was pregnant or had a breastfeeding baby. A sample of 110 men were selected using purposive sampling approach and a 6-point Likert scale questionnaire was administered to them. From the total of 110 questionnaires distributed, only 100 were completed and returned. The response rate was 91%.

4.1. Validity and Reliability

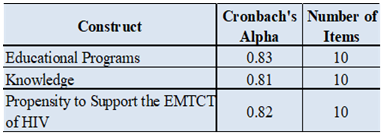

- For this study, face validity was ensured through the use of previously validated measures (Omondi et al., 2012; Hembah-Hilekaan et al., 2011; Olugbenga-Bello et al., 2012; Geoffery, 2011), which were refined where necessary. The study made use of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to assess the internal consistency-reliability of the scale used. Reliability reflects that “the research instrument would yield the same findings if used at different times, or if administered to the same group over and over again” (Waters, 2011, p.39). The research instrument used for this study was reliable as shown in Table 4.1.

|

5. Findings and Discussion of Results

- Descriptive statistics were used “to describe the characteristics of the respondents” (Singleton and Straits, 2010, p.15). The Spearman correlation is used for ordinal data (Rebekić et al., 2015, p.49) and it was used in this study. As inferential statistics, the study used Partial Least Squares regression analysis. Inferential statistics allow researchers to “make inferences about the true differences in the population on the basis of the data. A basic principle of statistical inference is that it is possible for numbers to be different in a mathematical sense, but not significantly different in a statistical sense” (van Elst, 2015, p. 13).

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

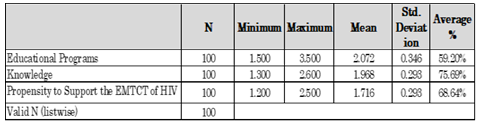

- According to van Elst (2015, p. 5), descriptive statistics are used to describe the characteristics of the respondents. Through the use of frequencies, means, modes, medians, standard deviations, and the coefficient of variation to summarise the characteristics of large sets of data. For the descriptive statistics, the individual scores were totalled and an average score was calculated. Descriptive statistics of the composite variables are summarized in Table 5.1.

|

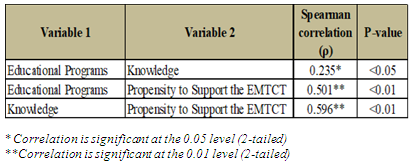

5.2. Correlations

- The relationships among the study variables were assessed using Spearman's correlation. Table 5.2 summarises the Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) and p-values for the different variables. The table shows the statistically significant positive correlation between educational programs and knowledge (ρ = 0.235); educational programs and propensity to support the EMTCT (ρ = 0.501); and between knowledge and propensity to support the EMTCT (ρ = 0.596).

|

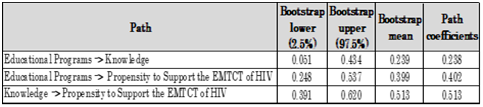

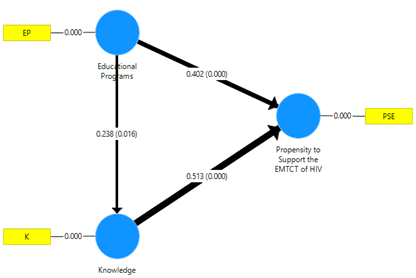

5.3. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression Analysis

- According to Maitra and Yan (2008, p.88), “PLS regression finds components from X that are also relevant for Y. Specifically, PLS regression searches for a set of components (called latent variables) that perform a simultaneous decomposition of X and Y with the constraint that these components explain as much as possible the covariance between X and Y.” In a PLS model, the significance of the paths and path coefficients is assessed using the bootstrap confidence intervals (Abdi & Williams, 2013). The bootstrap confidence intervals are presented in Table 5.3 below.

|

| Figure 5.1. Path, strength and significance of the path coefficients assessed by PLS (n=100) |

5.4. Summary of Key Findings

5.4.1. Influence of Educational Programs on Knowledge

- Consistently with the literature reviewed in Section 2 (Omondi et al., 2012; Hembah-Hilekaan et al., 2011; Olugbenga-Bello et al., 2012; Geoffery, 2011), the first hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between educational campaigns/programs and male partners’ knowledge about the EMTCT of HIV programme at the George Compound in Lusaka, was confirmed by relatively statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.238). This implies that ensuring adequate education/sensitization about HIV transmission and how to prevent it, MTCT of HIV and programme measures to reduce it, and importance of male involvement in EMTCT of HIV interventions will lead to enhanced knowledge of EMTCT of HIV programmes.

5.4.2. Influence of Influence of Educational Programs on Propensity to Support the EMTCT of HIV

- The second hypothesis, namely that educational campaigns/programs about EMTCT of HIV are likely to be positively associated with male partners’ propensity to support the EMTCT of HIV programme at the George Compound in Lusaka, was confirmed by statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.402). These results are consistent with the literature reviewed in Section 2 (Omondi et al., 2012; Hembah-Hilekaan et al., 2011; Olugbenga-Bello et al., 2012; Geoffery, 2011). Managerial implications are that ensuring adequate education/sensitization about HIV transmission and how to prevent it, MTCT of HIV and programme measures to reduce it, and importance of male involvement in EMTCT of HIV interventions will greatly enhance organizational male participation in EMTCT of HIV programme.

5.4.3. Influence of Knowledge on Propensity to Support the EMTCT of HIV

- The third hypothesis, which posited that male partners’ knowledge about EMTCT of HIV will positively influence their propensity to support the EMTCT of HIV programme at the George Compound in Lusaka, was also evidenced by strong statistically significant path coefficients (γ = 0.513). Again, these findings are consistent with the literature reviewed in Section 2 of this paper (Omondi et al., 2012; Hembah-Hilekaan et al., 2011; Olugbenga-Bello et al., 2012; Geoffery, 2011). Ensuring enhanced knowledge about HIV transmission and how to prevent it, MTCT of HIV and programme measures to reduce it, and importance of male involvement in EMTCT of HIV interventions will boost male participation in EMTCT of HIV programme.

6. Summary

- This study has contributed to supplementing to the EMTCT of HIV literature, especially in the Zambian context. The findings of the study revealed low scores for knowledge and male partners’ propensity to support the EMTCT of HIV programmes at the George Compound in Lusaka, which points to the need for urgent improvement in this regard. Although the average score for educational campaigns/programs was relatively high, there is always room for improvement. Sufficient evidence emerged from the study showing that it is imperative to ensure adequate male knowledge and educational campaigns/programs for their improved participation in the EMTCT of HIV programmes. These issues need to be effectively addressed and this will require unrelenting support from public health policy-makers, researchers, and other relevant stakeholders.

7. Conclusions

- In line with the findings of the research, interventions for the consolidation of effective male participation in the EMTCT of HIV programmes are found in, but not limited to, the recommendations below. Public health managers should ensure effective strategic planning incorporated into all stages of EMTCT of HIV programmes, and ensure that performance is objectively measured. They should also ensure that organizational processes, resources, skills development, and relevant equipment are sufficiently adequate to promote effective male participation in the EMTCT of HIV programmes. These recommendations will only be effective if there is a strong desire and commitment on the part of the public healthcare managers and policy-makers to actively work towards improvement in this regard.

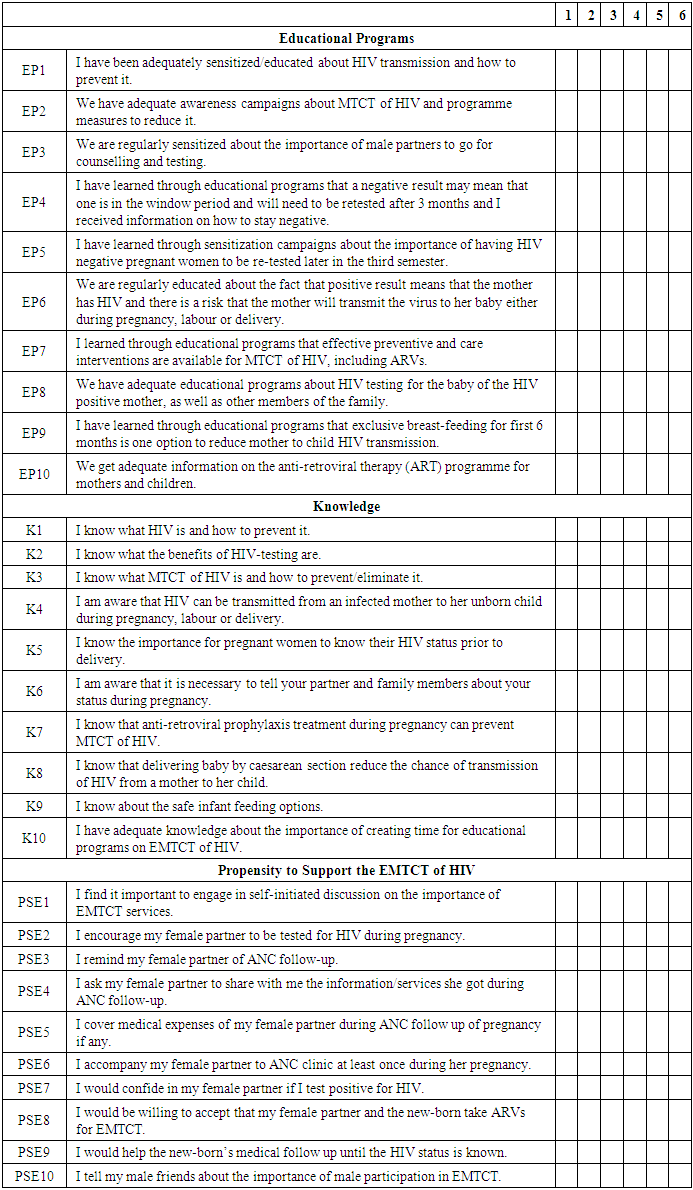

Appendix 1: Research Questionnaire

- Enhancing Male Partners’ Involvement in the Elimination of Mother-To-Child Transmission (EMTCT) of HIV in Zambia The aim of this research is to deepen the body of knowledge in the area of EMTCT of HIV by gauging the influence of knowledge and educational campaigns/programs on male partners’ propensity to support the EMTCT of HIV programme at the George Compound in Lusaka and - in so doing – serve as a guiding instrument for public health stakeholders for the improvement of EMTCT of HIV programme through enhanced knowledge and educational programs for male partners. Your responses will be treated as confidential and the information will not be used for commercial purposes.For each of the statements below, please rate your answer and mark with (x) the appropriate box as follows:Strongly disagree (1); Disagree (2); Disagree moderately (3); Agree moderately (4); Agree (5); and Strongly agree (6).There are no “right or wrong” answers to these questions; so please be as honest and thoughtful as possible in your responses. All responses will be kept strictly confidential.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML