-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2019; 8(1): 1-7

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20190801.01

Assessment of Hospital Staff Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAPS) on Activities Related to Prevention and Control of Hospital Acquired Infections

Hamid Ali Hamid 1, Mustafa Mohammed Mustafa 2, Mabrouk Al-Rasheedi 3, Bander Balkhi 3, Nagwa Suliman 4, Wejdan Alshaafee 3, Safa A. Mohammed 5

1Public Health Department Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Gazera University, Sudan

2Public Health Department, College of Public Health and Health Informatics, Qassim University, KSA

3Clinical Pharmacy Department, Collage of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia

4Ministry of Health, School Health Department, KSA

5Obstetric and Gynecology Department, College of Medicine, Gadaref University, Sudan

Correspondence to: Mustafa Mohammed Mustafa , Public Health Department, College of Public Health and Health Informatics, Qassim University, KSA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Study design: This is a cross-sectional study conducted in Alansar General Hospital AL-Medinah Al- Monawarah Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Objectives: The aim of this study was to assess the effect of hospital staff knowledge on practicing activities related to prevention of nosocomial infections. Methods: Self- administered pretested combined Arabic and English questionnaire was prepared. The questions of the questionnaire represent a minimum level of knowledge and practices for all components of infection control and prevention program which should be known and practiced by all hospital staff. The study population included all medical and non-medical staff in the hospital. A stratified random cluster sampling technique was used where (226) of the staff had been randomly selected from (520) of all hospital staff. The respondents were from different nationalities Arabic and non-Arabic countries. Results: The study revealed that the overall knowledge was found to be relatively good (60.4%), but there were some differences and variations among the staff according to sex, occupation, nationality, unit and years of experience. Regarding practices of infection control the overall practice for all staff were found to be least (24.6%). The overall compliance with standard precautions was found to be least (26.9%). Also there were variation according to sex, occupation, ling high risk medical wastes, and there is not enough training for medical staff which is considered as a base for good practice of infection control and prevention procedures, policies and guidelines. Conclusion: The study concluded that the overall knowledge of Alansar General Hospital staff regarding infection control and prevention policies procedures and principles relatively at a good level, but there were variations among the staff according to their sex, occupation, nationality, unit and years of experiences.

Keywords: Nosocomial, Noso, Acquired, Compliance, Non-medical staff, Infection control, Medina Monawara

Cite this paper: Hamid Ali Hamid , Mustafa Mohammed Mustafa , Mabrouk Al-Rasheedi , Bander Balkhi , Nagwa Suliman , Wejdan Alshaafee , Safa A. Mohammed , Assessment of Hospital Staff Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAPS) on Activities Related to Prevention and Control of Hospital Acquired Infections, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20190801.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The term nosocomial is extracted from (nosus) the Greek word which used to describe the disease and (komeion) which means protection or take some care [1]. The nosocomial infections are types of diseases that can be transferred from the health professionals, to their clients. It can be also the infection that happened as a result of transmission from patient to another patient(s). This is always hospital infection but symptoms or the development of disease will appear after leaving the hospital, in addition to the occupational infections which occur among staff of the hospital either medical or non-medical staff. Nosocomial infections happen through the world. The universal incidence is about 5–8% of admitted patients where one third of it can be prevented [2]. The greater incidence rates are in East Mediterranean and South-East Asia. A high frequency of nosocomial infections are always indicators of poor standard and quality of health establishments [3]. Nosocomial infections affect both developed and developing countries with some varieties in term of quantity. Infections acquired in healthcare units are major risk factors that increase morbidity among both admitted or outpatients. In fact, they are weighty limitations for both patients and community health [4]. In Saudi Arabia the hospitals infection control programs is not inveterate, it is a new approach started recently and developing fast.Saudi Arabia has trying to activate all infection control guidelines to improve the activities in the field of infection control in high standards [5]. In some urban hospitals in Saudi Arabia recorded 2.2% hospital infection monthly and other reports confirmed that hospital infection is still one of the most common health problems in Saudi Arabia [6]. The economic costs of managing the process of prevention and treatment of cases resulted from hospital-acquired infection are considerable. The increased length of hospital stay for infected patients is the greatest contributor to cost [7]. Hospital-acquired infections are the main cause of the irregularity between the resources identified for primary, secondary and tertiary care, and because of the diversion of resources that are primarily vulnerable to treatment for diseases that could have been easily prevented [8]. The variation in cost is mainly depending on the roots and sources of infections. It is confirmed that it can give 1 to 4 days more admission for hospital infection in a urinary tract infection, 7 days for blood stream infection, and 7–30 days for pneumonia. The CDC has recently reported that US$ 5 billion are added to United States health costs every year as result of nosocomial infections [9].

1.1. Classification of Infections

1.1.1. Endogenous Infection

- The initial stage of infection happens when normal flora changes to pathogenic bacteria as a result of change of normal life’s habitats, harm of damage of skin and misuse of antibiotic use. About 50% of nosocomial infections are caused by this way.

1.1.2. Exogenous Cross-infection

- Mainly through polluted hands of hospital staff (medical and non-medical), visitors and patients and co- Patients.

1.1.3. Exogenous Environmental Infections

- Beside the hospital staff, patients, and other persons there are several types of micro-organisms living in the hospital environment (hospital flora): In water, damp areas and occasionally in sterile products, and mycobacterium. These micro-organisms can be found on items such as equipment’s and in food supplies. Some important equipment's that essential to be used may increase risk of infection e.g. urinary catheters, I.V.L (intravenous line) inhalation therapy (ventilator), surgery and misuse of antibiotics [10].

1.2. Types and Sites of Nosocomial Infections

1.2.1. Urinary Tract Infections (U.T.I)

- This is the most known and common nosocomial infections. 80% of infections are related to the use of a bladder catheter. UT I are linked with less morbidity comparing with others nosocomial infections but can sometimes lead to bacteremia and death. The bacteria responsible arise from gut flora either normal (E.coli) or acquired in the hospital (mult-iresistant Klebsiella [11].

1.2.2. Surgical Site Infections (S.S.I)

- Surgical or operation room’s infections are also frequent. The incidence varies from o.5% to 15% based on the kind of the operation and patient status. The infection is always happen during the operation itself, either from exogenous sources e.g. from air, surgical equipment’s, or others staff, or endogenously from the flora on the skin or in the operative site, or in some cases from blood donated in surgery [12].

1.2.3. Nosocomial Pneumonia

- This can happen among different groups of patients. The most serious are patients that using ventilators in intensive care units, where the rate of pneumonia is 5% per day. It is evidenced that there is high rate of morbidity associated with ventilator–associated pneumonia. They are always endogenous (digestive system or nose and throat), but may be exogenous, often from contaminated respiratory equipment’s [13].

1.2.4. Bacteremia (blood Stream Infections)

- These types of infections represent a small percentage of nosocomial infections. (approximately 5%), but case morbidity is high -more than 50% for some microorganisms. The incidence is increasing; particularly for certain organisms such as multi resistant coagulase–negative staphylococcus and Candida spp. Infection may occur at the skin entry site of the intravascular devices, or in the subcutaneous path of the catheter. The main risk factors are the length of catheterization, level of asepsis at the insertion, and continuing catheter care [14].

1.2.5. Skin Infections (S.I)

- Skin and soft tissue infections, open sores (burns, and bedsores) encourage bacterial colonization and may lead to systematic infection [15].

1.2.6. Gastrointestinal Infections (G.T.I)

- Gastrointestinal infections are the most common nosocomial infection in children, where rotavirus is chief pathogens. Clostridium difficult is the major cause of nosocomial gastroenteritis in adults in developed countries [15].

1.2.7. Blood Borne Infections (HIV, HBV, and HCV)

- Healthcare workers may be exposed to the risk of infection with blood borne viruses such as HBV, HCV, and HIV via contact with blood (and other body fluids) in the course of their work the form of exposure most likely to result in occupational BBV infection is a needle stick injury.Approximately 3 million healthcare workers experience percutaneous exposure to blood borne viruses each yea. This result in an estimated 16000 hepatitis C, 66000 hepatitis B, and 200 to 5000 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection annually. More than 90% of these infections occurring in low income countries, and most are preventable. Several studies report the risks of occupational BBV infection to in high-income countries where arrange of preventable interventions have been implemented. In contrast, the situation for in low-income countries is not well documented, and their health and safety remain a neglected issue [16].

1.2.8. Tuberculosis

- Tuberculosis (TB) caused by the slow growing bacteria (mycobacterium tuberculosis). Health care workers have a greater risk than the others for acquisition. Patients who are infected but undiagnosed pose the greatest risk of transmission [17].

1.2.9. MRSA (Methicillin- Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus)

- Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most commonly isolated bacterial pathogens. It can cause infections ranging from minor skin pustules to serious life-threatening ones such as septicemia, endocarditis and brain abscess. 20-30% of individuals carry staphylococcus aureus in their nose and on moist areas of skin particularly the perineal area. It is not surprising, therefore, that cross infections due to this organism occur from time to time in hospitals. The source of such infections is usually a patient or a member of staff who may be colonized or infected with the organism [18].

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- This study used a survey method, applying structured self-administered pretested combined Arabic and English questionnaire.

2.2. The Study Population

- The study included all medical and non-medical staff in the hospital (520). A stratified random cluster sampling technique was used to identify subjects to be included into the study.

2.3. Study Area

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the one of the biggest Asian countries. The kingdom hosts pilgrims from more than 140 countries for each Hajj season which is extraordinary infection control challenges in an unprecedented scale. Medina Monawara is one of the Islamic holly cities in kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The health institutions in Medina Monawara consist of the General Directorate of Health Affairs which is in charge of all governmental and private health institutions in Medina Monawara Area. Inside Medina Monawara there are 9 hospitals, 32 primary healthcare centers. The study was conducted at Alansar General Hospital which is one of five biggest governmental hospitals in Medina Monawara. It lies in the central part of Medina Monawara, with 100-beds capacity. The manpower of is about 520 (medical and non-medical staff), where 90(17.3%) are physicians, 196(37.7%) nurses 26(5%) are laboratory Technicians, 28(5.4%) are pharmacists, 29(5.6%) X-ray Technicians, 4(0.8%) Operation Technicians, 4(0.8%) Anesthesia Technicians, 6(1.2%) Dieticians, 3(0.6%) Health Inspectors, 30(5.8%) Administrators, 6(1.2%) Medical equipment’s maintenance Technicians, 10(1.9%) Drivers, 70(13.5%) Housekeepers, 6(1.2%) Maintenance Technicians, 12(2.3%) others include security, guards etc.

2.4. Methods of Data Collection

- Data collected through use of a questionnaire about knowledge, attitudes and practices of the hospital staff regarding the infection control. It was a self-administered structured questionnaire written in both English and Arabic languages and validated by public health specialists from faculty of public health and health informatics. The questions designed to collect the most relevant information about the knowledge, attitudes and practices of the hospital staff regarding the infection control. The questionnaire included questions about demographic characteristics such as sex, age, nationality, occupation and evaluation of knowledge, practices of infection control in addition to prevention policies. The questionnaire was tested by Cronbach’s alpha and giving score 0.891, which showed high reliability and consistence of the questionnaire items. The respondents were asked to indicate using 2 points Likert scale (Yes, No) for identification, and 3 points Likert scale (agree, disagree, undecided) for evaluation of knowledge, and 4 point Likert scale (always, sometimes, rarely, never) for evaluation of infection control practices.

2.5. Data Analysis

- The data was edited and reviewed during and after leaving the respondents. The researcher checked for all the parameters involved in data analysis. The data was analysed through Statistical Software Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 2.Inclusion criteriaThe study included all medical and non-medical staff in the hospital from different nationalities in all departments in the hospital.Excluding criteriaPar timers and non-resident employers (visitor consultant).Ethical considerationThe study obtained a written informed consent from the ethical committee in Alansar General Hospital, in addition to personal agreement from all respondents written clearly in the top of the questionnaire and their signatures were required before they fill the questionnaires.

3. Results

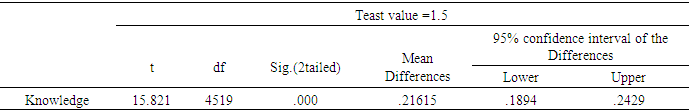

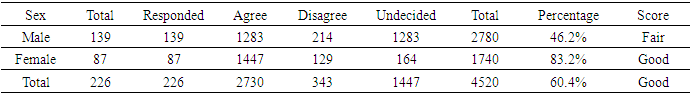

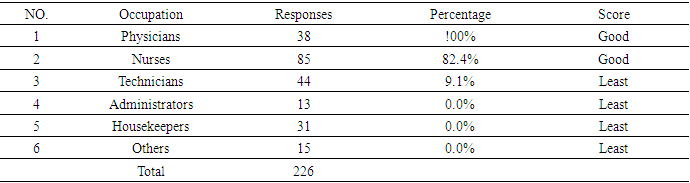

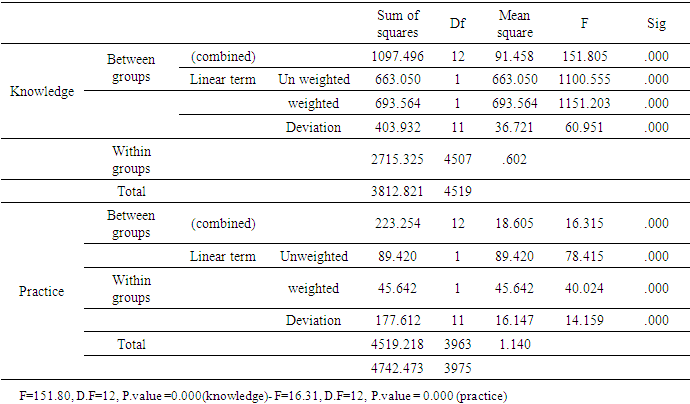

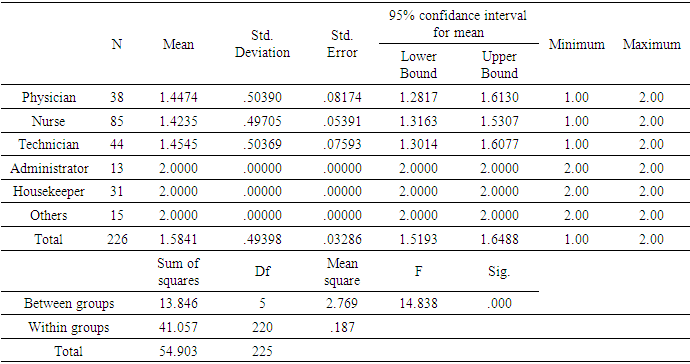

- A total of 226 hospital staff was engaged in the study. The majority of which were males 139(64.6%) and females 87(35.4%) 38(16.8%) were physician, 85(37.6%) nurses, 5% were laboratory technicians, 5.4% were pharmacist, 5.6% X-ray technicians, 0.8% operation technicians, 0.8% anesthesia technicians, 1.2% dieticians, 0.6% health inspectors, 13(5.8%) administrators, 1.2% Medical equipment’s maintenance technicians, 1.9% drivers, 13.5% housekeepers, 1.2% maintenance technicians, 15(2.3%) others include security, guards etc.Regarding the knowledge level test, the respondents has passed the test value (1.5–2) with df=4519, P.value=0.000 and obtained the value=1.71(Fair) level for knowledge. This indicates that all the respondents have acceptable level of knowledge on hospital acquired infections, risk and precautions (Table 1).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

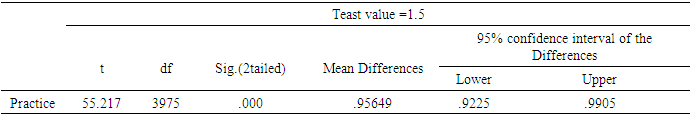

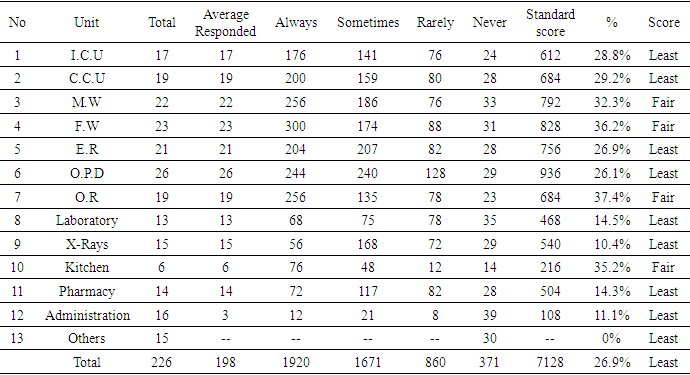

- The study has revealed that the Overall knowledge was found to be relatively high (60.4%), but there were some differences among the respondents, Females were found to be more knowledgeable than males (females = 83.2%) and males = (46.2%).The study showed that, some specializations have a high level of knowledge and practice more than others. In the absence of local training this may be due to previous experience and knowledge. Also the study confirmed that non-medical staff had least level of knowledge complaining with the medical staff.There was a wide range between knowledge and practice, despite the good level of knowledge among the majority of the respondents, there was a least level of practice which means knowledge was not translated into practice. Practice depends on external and internal factors, like work environment, administration, infection control committee. The implementation and updating of protocols concerning the control and prevention of infection inside the hospital. All these factors may lead to a least level of practice that is according to WHO guideline for patients care and safety [20].Regarding the level of knowledge and practices for variance according to unit, this variation can be seen in practicing infection control and prevention which range from (2.17 up to 3.36) for all units. Some unit were more strict about the implementation of infection control and prevention policies and procedures than others, this may be due to high level of risk to which the staff may be expose, or to the number of nosocomial infection cases previously discovered. Study conducted in a Tertiary Referral Center in North-Western Nigeria showed strictly concerns to infection control protocols and guidelines among staff of units that prompted high prevalence of nosocomial infections comparing with non or less cases units with (P = 0.001) [21].Regarding the level of knowledge about Standard Precautions according to occupation There was significant differences according to occupation, the knowledge of physicians, nurse and technicians on standard precautions seem to be equal (mean=1.4), this result is contradicted with result revealed from recent study conducted in Eastern province in KSA which showed that physicians achieved higher score of Knowledge compared to nurses (P<0.05) [22]. The same applies to the non-medical personnel (mean=2.00). According to test value (1-1.5) this is considered a Good level of knowledge. Medical staff had a Good level of knowledge and non-medical staff had a least level of knowledge. Only (30.1%) of the respondents had training about infection control guidelines. The non-medical staff did not attend any training program.Regarding units, female wards and kitchen staff were more strict, complying and adhering with Standard Precautions than other unit’s staff. This is because food handlers have to be strict adhering and complying with Standard Precautions to avoid transmission of food borne diseases to the admitted patients. These results are consistent with WHO guideline on Prevention and Control of Hospital Associated Infections 2002 [23]. In the other units the score of compliance and adherence with standard precautions were relatively least especially in I.C.U (28.8%), C.C.U (29.2%). These two units admitted always imuno-compromised patients, so their staff needs to be strict on compliance with Standard Precautions for protection of these patients. Unfortunately laboratory staff compliance with standard precautions was found to be (least), (lab. Staff Score (14.5%) but operation room staff score was (Fair) = 37.4%). Laboratory and operation room are considered as a high risk areas, due to the risk factors for the staff and patients, so the staff working in these units need to be stricter, complying and adhering with standard precautions. The primary hazards to the laboratory staff related to their exposure to infectious aerosols, autoinoculation, and ingestion and cross-infection.

5. Conclusions

- The study concluded that the overall knowledge of Alansar General Hospital staff regarding infection control and prevention policies procedures and principles relatively at a good level, but there were variations among the staff according to their sex, occupation, nationality, unit and years of experiences. On the other hand the overall practice, compliance and adherence with infection control, policies, procedures and principles were relatively least, also there were variations among the respondents according to their sex, occupations, nationality, unit and the years of experiences. The actual practices, compliance and adherence with infection control and prevention policies, procedures and principles in hospital was lower than expected.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I am extremely indebted to the continued support and encouragement of Dr: Essa Mohamed Yusuf, Dr: Imad Ajack, and Prof: Mahmoud Abdul Rahman for their meticulous attention in supervising this study. I also wish to extend my thanks to all staff of Alansar general hospital specially the nursing staff for their assistance in conducting the questionnaire pretesting.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML