-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2018; 7(1): 14-20

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20180701.03

Gender, Adiposity and Age as Predictors of Quality of Life in Costa Rican University-Retirees

Luis Solano-Mora1, Gerardo Araya-Vargas1, 2, Jairo Jiménez-Torres3, José Moncada-Jiménez2, 4

1School of Human Movement Sciences and Quality of Life, Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

2School of Physical Education and Sports, University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

3Chorotega Regional Office, Nicoya Campus, Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica

4Human Movement Sciences Research Center (CIMOHU), University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Correspondence to: José Moncada-Jiménez, School of Physical Education and Sports, University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

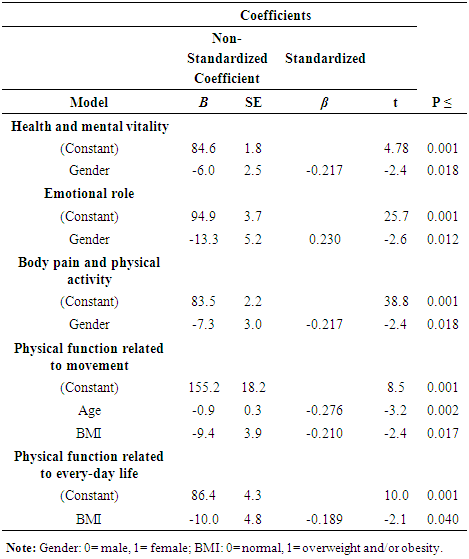

This study investigated predictors for quality of life in Costa Rican university-retirees. Volunteers were 119 adults (60 female and 59 male) ages from 52 to 80 years old. Age, gender, education, job position, retirement date, physical activity, and body mass index (BMI) were considered predictor variables. The modified SF-36 questionnaire was used to measure quality of life. Multiple linear regression analyses were calculated to determine predictors for quality of life. Significant associations were found between gender and the dimensions of Health and Mental Vitality (R2 = 0.039, p = 0.018), Emotional Role (R2 = 0.045, p = 0.012), and Corporal Pain and Physical Vitality (R2 = 0.039, p = 0.018). BMI and age were significantly related to Physical Function Related to Walking (R2 = 0.105, p = 0.011), and only BMI was significantly associated with Physical Function Related to Daily Activities (R2 = 0.027, p = 0.040). In conclusion, gender, age and BMI were significant predictors for quality of life in university-retirees.

Keywords: Retirement, Quality of Life, Physical Activity, Education, University-retiree, Adiposity

Cite this paper: Luis Solano-Mora, Gerardo Araya-Vargas, Jairo Jiménez-Torres, José Moncada-Jiménez, Gender, Adiposity and Age as Predictors of Quality of Life in Costa Rican University-Retirees, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2018, pp. 14-20. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20180701.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In 2009, the tabloids reported that Costa Rica was the happiest country in the world [1]. Although in Costa Rica the message was misinterpreted because locals believed that they were blessed and lucky to live in the happiest country in the world, the report accurately indicated that the country did not reach that classification according to The New Economics Foundation (NEF), instead, it was considered the most efficient country in pointing towards happiness. In other words, the NEF’s Happy Planet Index (HPI) indicated that Costa Rica was making important efforts so that its inhabitants had longer and happier lives. The HPI is an indicator that globally represents sustainable human well-being; in other words, a measure of better quality of life (QOL) based on lived wellness, life expectancy and ecological footprint [2]. The NEF also ranked Costa Rica first in 2012. With Scandinavian countries leading the top three positions, last year’s World Happiness Report [3] ranks Costa Rica 13th in the world, second in America just behind Canada, and first in Latin America. These data suggest that Costa Rica offers significant living conditions worthy to study [2].Modern societies are facing countless challenges due to the increasing global life expectancy combined with the rapid growth of the elderly population [4, 5]. One of these challenges would be to determine how increased life expectancy could affect people’s transition into retirement [6]. An important element within this context will be the retirement process itself, which includes complex features such as a good post-retirement income, access to health services, and continuing education. The analysis of these factors generates an enormous pressure to government’s retirement systems around the world, especially in developing economies like Costa Rica’s [6].It has been estimated that in the United States, for instance, adjustments would be needed in their public health system because as the baby-boomers reach retirement age, the health system would no longer be able to finance the economic costs of supporting the living conditions of that age group [5]. Costa Rica has an unusually high life expectancy for a middle-income country, even higher than that of the United States [7]. According to Fernández and Robles [8], Costa Rica faces a similar phenomenon due to the increasing growth of the older population and simultaneous reduction of the younger labor force. Consequently, the possibilities of supporting the retirement system would be challenging in a near future. To relieve this generational tension, Bredt [6], describes some solutions as those discussed in Germany, taking into account the possibility of choosing a retirement ager over 60 years of age. This situation is also discussed in Russia, China, and Argentina where they are examining the aging population phenomenon [9-11]. There are several studies showing similar perspectives. For example, Cooke [12], showed that aging societies in developed countries would trigger a great pressure on the retirement systems, especially in those countries with reduced birth rates like Costa Rica. Midanik, Soghikian, Ransom and Tekawa [13], found a positive effect of retirement on people’s health. For instance, retirees showed higher levels of physical activity than those currently working. Increased levels of physical activity in middle-aged and older adults have been related to an overall lower mortality even in the presence of existing cardiovascular or metabolic diseases [14]. Other evidence suggest that the psychological wellness on retirees could be associated with a higher income, a better subjective perception of health, and an increased locus of control [15]. However, some researchers demonstrated that an early retirement is not necessarily related to successful survival rates [16], and that there is no concluding evidence demonstrating that retirement might positively change perceived health due to a combination of a lack of job-related stress and increased physical activity [17].There is a cluster of economic, environmental, social, physical and psychological variables related to human wellbeing. The body mass index (BMI = body weight/body height2), a surrogate marker of a person’s body adiposity, is an anthropometric variable related to QOL. The BMI is well established for diagnosing overweight and obesity and correlates with several medical conditions. Østbye, Dement and Krause [18], found that workers with normal BMI lost fewer workdays and had less medical compensation payments than workers categorized as having type III obesity. The latter had the poorest health indicators and the combination of both obesity and a high-risk job produced even worse outcomes. It is widely recognized the strong association between obesity and insulin resistance, diabetes, high cholesterol and elevated triglycerides [19]. Jones, Latreille, Sloane and Staneva [20], indicated that elderly adult workers may have more factors that affect their health than younger workers, while Nelson, et al. [21], found that workers in a flexible work environment showed better physical activity levels. Physical activity has been described a one of the best interventions to reduce several physical, metabolic and mental diseases [22-24].There is an extensive body of knowledge on wellness from European and North American countries, especially the United States. In Central American countries, there is a dearth of evidence showing predictor variables related to wellbeing, including QOL. Therefore, studying potential predictors of wellbeing is important to contribute to the global understanding of this construct. Based on this context, the aim of this study was to explore QOL predictors in retirees from a major public university in Costa Rica.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- This is a cross-sectional study conducted on retirees from a public university located in Costa Rica. To start the recruitment process, we contacted the Educational and Social Welfare Office of the University Union. The purpose was to explain the research objectives and to request the contact list of retirees from the institution. Based on this information, a sample of 119 university-retirees (50.4% women and 49.6% men) was selected with ages ranging from 52 to 80 years old.

2.2. Measurement Instruments

- The “Quality of Life Predictive Factors of University-Retirees” questionnaire was uploaded in a website [25]. To generate a battery test, three instruments were used. First, a demographic questionnaire focused on age, gender, and formal education (incomplete elementary, complete elementary, incomplete middle-school, complete middle-school, incomplete high-school, complete-high school, incomplete bachelor degree, bachelor degree, licentiate, master's degree, and doctorate). In addition, participants were instructed to complete information regarding the job position area (administrative or academic), time of retirement (< 1 year, between 1-5 years, between 6-10 years, between 11-15 years, between 16-20 years or > 21 years). Finally, body weight and body height were masured. The second instrument was the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36), version 2. This test has been extensively reported in the literature and shows appropriate reliability > 0.7, and content, criteria, concurrent, and construct validity [26]. The original version of this questionnaire had nine subscales: 1) Physical function (10 items); 2) Physical role (4 items); 3) Body pain (2 items); 4) General health (5 items); 5) Vitality (4 items); 6) Social Functions (2 items); 7) Emotional Role (3 items); 8) Mental Health (5 items), and 9) Health evolution (1 item) [27]. However, Solano-Mora, Moncada-Jiménez, Araya-Vargas and Jiménez-Torres [28], observed the factorial validity of the test in a Costa Rican-retiree sample and found a different factorial structure: 1) Health and mental vitality; 2) Physical role; 3) Emotional role; 4) Body pain; 5) Physical activity related to movement; 6) Physical activity related to daily routine activities; 7) General Health, and 8) Physical activities for social life. Therefore, the Costa Rican validated scale was used in this study.The third instrument included was the long form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [29]. The instrument assessed 5 dimensions: 1) Job-related physical activity; 2) Physical activity as transportation; 3) Housework, house maintenance, and caring for family; 4) Recreation, sport and leisure-time physical activity; 5) Sitting time. In this questionnaire, people answered how many times per week they did the particular activity asked and the time (in minutes) devoted for each one. Then, an algorithm was applied and participants were classified as either doing vigorous and moderate physical activities [30]. The IPAQ has been widely studied, showing reliability scores between 0.80 and 0.89 [29, 31]. Finally, body weight was measured on an electronic scale and a measuring tape was used to measure body height. From these measures, BMI was calculated.

2.3. Measurement Procedures

- Volunteers were given an introductory explanation about the research objectives, and once the terms were accepted, they were appointed to the School of Human Movement Sciences and Quality of Life, at the National University to read and sign an informed consent. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical institutional standards and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments [32]. Then, participants were weighed and measured and, finally, they anonymously filled in the questionnaire. All the information collected was downloaded into a personal computer, coded to preserve confidentiality, and used for further statistical analyses.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Statistical analysis was made using the IBM-SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). Data are presented as percentages, mean (M), standard deviation (± SD), and 95% confidence intervals (CI95%). A regression model was studied to understand the predictive variables (gender, academic level, time of retirement, BMI, and physical activity levels) and the criteria variable (QOL dimensions). Predictive variables gender and BMI were re-codified as binary variables (0= male, 1= female; 0= normal, 1= overweight and/or obesity, respectively), while academic level and time of retirement were considered ordinal variables; age and physical activity were continuous variables. Consequently, a multiple regression analysis was applied, in which the model studied had Ŷ = a + b1(X1) + b2(X2) + … bn(Xn) ± SEE. In the model, Ŷ is the dependent variable, a the constant, X represented each predictive variable, and SEE the standard error of the estimate [33, 34]. The predictive variables were entered using the stepwise method in SPSS, and normality and regression basic assumptions of homoscedasticity and linearity were studied [35].

3. Results

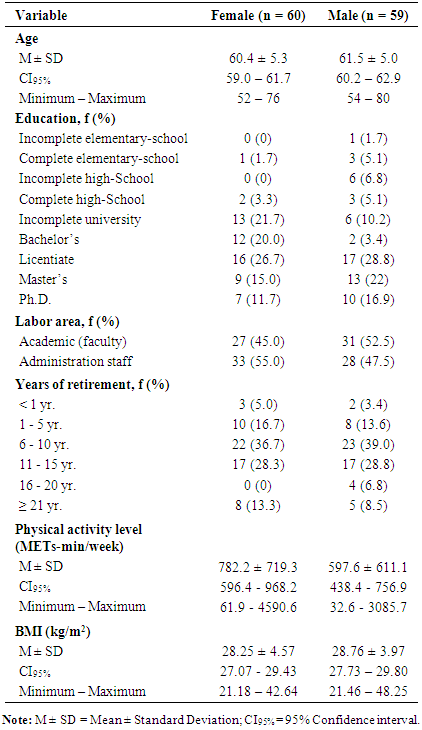

- The sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the participants were 60.4 ± 5.3 yr. and 61.5 ± 5.0 yr. for females and males, respectively. The majority of participants (~27%) had a licentiate level of education, an intermediate degree offered in Costa Rica equivalent to a master’s degree in some countries (i.e., courses beyond undergraduate level and writing a thesis). Most retired females used to work in administration and the majority of males worked as faculty. Most retirees had between 6 and 10 years of retirement already. Female’s physical activity levels were higher than males’ (Table 1).

|

|

4. Discussion

- The aim of this study was to investigate the possible predictive variables related to QOL in retirees from a major public university in Costa Rica. The most important finding was that gender (in three dimensions), BMI (in two dimensions), and age (in one dimension) were the best predictors regarding the sample’s QOL in comparison with the academic level, time of being retired, and physical activity levels.Using the SF-36 modified and adapted for the sample was one of the most relevant aspects in this study. Walters, Munro and Brazier [36], indicated that public health institutions should evaluate elderly people’s QOL. For that reason, using adequate and adapted instruments is mandatory. Mojon-Azzi, et al. [17], reported that one of their study limitations was that they used general health measures and promoted using specific instruments that might show more health-related dimensions. The original SF-36 is an instrument specific to assess QOL and it was adapted for this study, which increased the validity of the present findings [28].Quick and Moen [37], did not observe differences between retiree-men and retiree-women on their QOL. The researchers evaluated the perceived quality of retirement by asking: a) “how satisfied are you with your retirement?” and b) “how do you compare retirement with that time when you worked based on the last five years?” Both questions were answered using a Likert scale and the researchers found that men showed a slight dissatisfaction compared to women, while women mentioned having a good quality of retired-life associated to having a better health, a new part-time job and a good income. In our study, we observed significant differences between men and women on their QOL perceptions, where men reported a higher perception compared to women.Educational levels and age are also critical factors in QOL perceptions [38, 39]. This is an important element to be considered for those responsible for elderly health promotion programs due to the lack of reading comprehension of the elderly when answering the questionnaires. Thus, people responsible for applying surveys should consider the academic level of the sample to reduce interpretation bias. In the present study, one of the researchers was always present to answer any questions the elderly might have had when answering the questionnaire to guarantee the correct comprehension of the questions being asked. However, in the present study, education level was not a significant predictor QOL variable. Most females (95.1%) and males (81.3%) in this study reported incomplete university to the highest university degree education, which reduced heterogeneity in the sample.Sjösten, Kivimäki, Singh-Manoux, Ferrie, Goldberg, Zins, Pentti, Westerlund and Vahtera [40], found that four years before and after retirement the physical activity levels were increased in those who were not previously physically-active. They also found that the retirement transition path is related to a good health. Consequently, to inquire more in the diverse variables that affect the QOL in this age-group is mandatory. In this study, we did not observe that the retirement time was a significant predictor of QOL in any of the dimensions studied.In relation to physical activity during the retirement, there are some contradictory findings. Berger, Der, Mutrie and Hannah [41], showed increased physical activity levels following retirement, while the opposite was reported by Slingerland, et al. [42]. In this study, we did not find that the physical activity was a significant predictor of QOL. This result was unexpected due to the fact that physically active people have reported better QOL than sedentary people [43]. Therefore, further research is needed focused on this topic in other Costa Rican retiree groups.In this study, the BMI was the strongest predictive variable of QOL. In general, results showed consistency with data reported by others [18, 44], who indicated that the highest the BMI (high levels of overweight and obesity), the lowest would be the subjective wellbeing. This evidence is important due to the high BMI levels are strongly associated not only to increased prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and some types of cancer, but also to several psychological and perceptual variables such as negative body image, low self-esteem and increased risk of dementia [45-48]. Although in this study physical activity was not a significant predictor of QOL, its inverse association with BMI becomes an interesting factor to maintain BMI levels within healthy standards. Lang, Guralnik and Melzer [49], found that overweight was associated with dysfunctional health in middle age and older people, while physical activity showed to be a protective factor. Even though this predictive variable did not explain the model of QOL in the present study, we recommend to continue studying this issue since elderly are the most sedentary population of all [50, 51].To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to determine significant QOL predictors in a Central American country. It has been suggested that violence is inversely related to wellbeing and happiness [52]. Costa Rica abolished the military in 1948; however, most of the surrounding countries still have military and have lived intense war conflicts up to 1987 when the region ceased major military actions. Within the context of this study, it is important to consider that since 1948 Costa Ricans devoted the majority of their national budget mainly to education and health, whereas their counterparts spent enormous amounts of theirs to supporting military forces. Recent evidence suggest that health indicators are better in Costa Rica than in other Central American countries [53]. Since educational level has also been related to better perceived wellness [54], it is expected that Costa Ricans would show better wellness and QOL than their neighbors; however, comparative studies are warranted to test this hypothesis. The workplace did not predict QOL in the regression analysis applied. This finding contradicts a previous a study showing that men and women having a full-time work reported better QOL versus those working overtime or only a few hours [55]. Further research should analyze these variables and work conditions as well, as potential predictor factors determining QOL.

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, gender, BMI, and age are the most important predictive factors of well-being as determined by QOL perception in university-retirees. Aging is a complex process in which multiple elements can influence wellness. For this reason, it would be necessary to include other socio-economic, metabolic, and environmental variables in further studies. This would help to better understand the wellness dimension in order to focus on the best strategies to promote QOL for both, those near retirement and those already retired.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Our gratitude to Jeannette Soto, professor from the School of Modern Languages of the University of Costa Rica for editorial assistance. This research was supported by the Cooperativa Universitaria de Ahorro y Crédito R.L. (COOPEUNA), Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML