-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2018; 7(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20180701.01

An Assessment of Onset-to-Intervention Time and Outcome of Lassa Fever during an Outbreak in Edo State, Nigeria

Ireye Faith1, Aigbiremolen Alphonsus O.2, Mutbam Kitgakka Samuel1, Okudo Ifeanyi1, Famiyesin Olubowale Ekundare1, Asogun Danny3, Braka Fiona1, Irowa Osamwonyi4, Abubakar Ahmed1, Iretoi Grace1, Ejiyere Harrison3

1World Health Organization, Nigeria

2Cedar Centre for Health and Development, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria

3Department of Community Medicine, Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, Irrua, Edo State, Nigeria

4Ministry of Health, Edo State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Aigbiremolen Alphonsus O., Cedar Centre for Health and Development, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

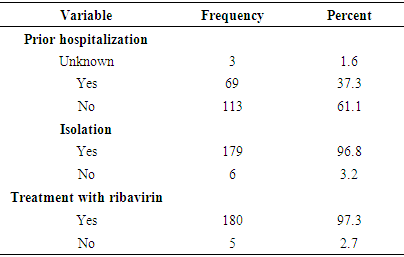

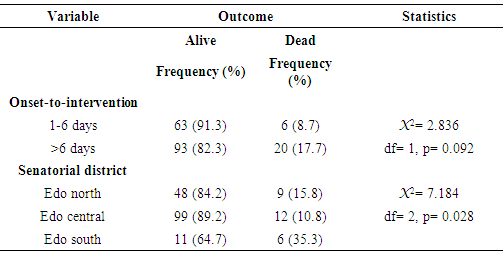

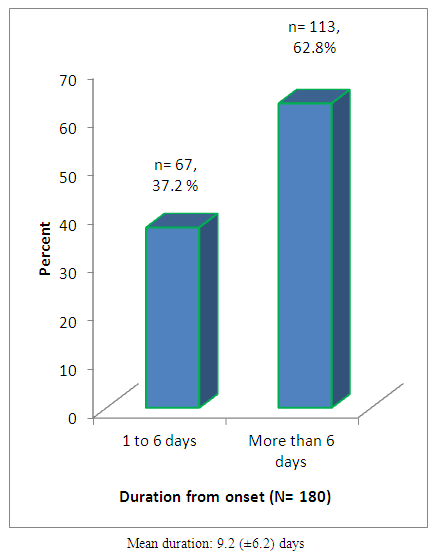

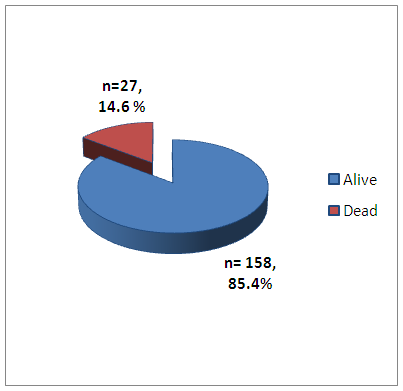

Lassa fever, an acute febrile illness caused by the Lassa virus, is endemic in Edo State Nigeria with yearly outbreaks. In the 2018 outbreak, about 42% of cases were already reported from Edo State as at the time of this paper with cases of late presentation observed. This study sought to investigate the duration of time of onset of illness to commencement of treatment and the implications on disease outcome among patients. Data from case investigation forms (CIFs) filled by staff of the WHO, Edo State were analysed using IBM SPSS version 21. A total of 185 were investigated during the period. Onset-to-intervention time was defined as the period (in days) from onset of illness to commencement of treatment with ribavirin and was grouped into early (1-6 days) and late (>6 days) presentation. Only 37.2% cases presented for treatment within 6 days of onset of illness. More than a tenth (14.6%) of the case died and 85.4% survived. Although the proportion of survivors was higher among patients that presented earlier than late presenters (91.3% versus 82.3%), the difference was not statistically significant (X2= 2.836, p= 0.092). The proportion of survivors was highest among cases in Edo central senatorial district and the difference was statistically significant (X2= 7.184, p= 0.028). Early presentation improved survival of patients and proximity of cases to the only available diagnostic and treatment centre was significantly associated with survival. In addition to building better capacity for quick referrals from primary care facilities, longer-term control plans should include increasing number of diagnostic and treatment facilities in the State.

Keywords: Lassa fever, Onset, Outbreak, Edo State, WHO

Cite this paper: Ireye Faith, Aigbiremolen Alphonsus O., Mutbam Kitgakka Samuel, Okudo Ifeanyi, Famiyesin Olubowale Ekundare, Asogun Danny, Braka Fiona, Irowa Osamwonyi, Abubakar Ahmed, Iretoi Grace, Ejiyere Harrison, An Assessment of Onset-to-Intervention Time and Outcome of Lassa Fever during an Outbreak in Edo State, Nigeria, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20180701.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Lassa fever is an endemic viral haemorrhagic fever in some West African countries including Nigeria [1, 2]. It is an acute illness caused by the Lassa virus, an Arenaviridae specie [3, 4]. The primary animal host is the multi-mammate rat (Mastomys natalensis), which is a rodent indigenous to most of Sub-Saharan African countries. Though the vector host is not known to develop the disease from the virus, human contact with the infected rodent, its droppings, urine, blood or any other body fluid often lead to Lassa fever disease thus making it a zoonotic infection [5]. Certain factors related to human and rodent behaviour have been identified as important risk factors in the transmission of Lassa fever. These include poor housing, poor personal and domestic hygiene, unsafe food practices, unkempt and bushy house surroundings and insanitary waste management practices [6-8].Yearly outbreaks of Lassa fever occur in Nigeria. The 2018 outbreak is the largest ever with some evidences indicating both rodent-to-human transmission and human-to-human transmission [9]. The recent outbreak has taken its toll on both the affected communities and the healthcare delivery system. As at 3rd June, 2018, 181 out of the 432 (42%) confirmed Lassa fever cases were from Edo State and 13 of these were health workers [10]. Presently, there is only one confirmatory laboratory and one case management centre for Lassa fever (both at Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, Irrua) in Edo State. Many suspected or probable cases of Lassa are unable to be diagnosed or managed immediately due to distance of the facility from many towns and villages in the State. In addition, the similarity between symptoms of Lassa fever and many other endemic diseases like malaria, typhoid fever and respiratory tract infections creates diagnostic difficulties. Thus when patients with suspected symptoms of Lassa fever present in peripheral health care facilities, difficulties with testing, delay in diagnosis and challenges of logistics of referral to the treatment centre all contribute to the duration of period between onset of illness and commencement of definitive treatment [11].The implications in the delay of commencement of definitive treatment for Lassa fever are significant. Lassa virus is known to have affinity for renal tissues and demonstrates worsening nephro-toxicity as well as thrombocytopenia with disease progression [12, 13]. In addition, the intervening periods spent by Lassa patients at home, in the community and in peripheral health care facilities increase the risk of spread of the disease to household members, intimate contacts and health care workers. Early commencement of treatment with ribavirin (within 6 days of onset) for Lassa fever is associated with improved outcome as demonstrated with significantly lower case fatality rates [14, 15]. Therefore, the aim of this research was to investigate the duration of time of onset of illness to commencement of treatment and the implications on disease outcome among patients who had Lassa fever during the 2018 outbreak of Lassa fever in Edo State.

2. Methodology

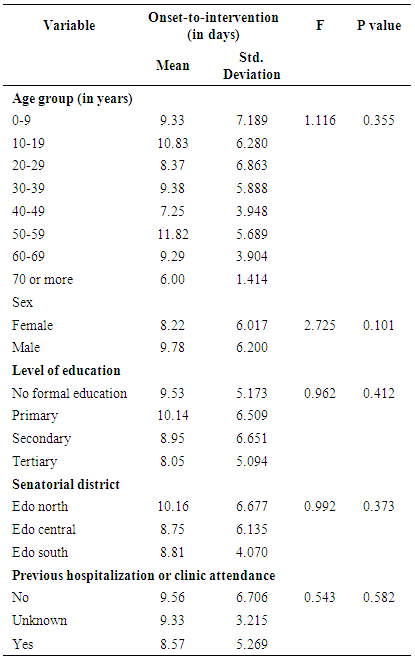

- Secondary data was used for this study. Data from case investigation forms filled for all confirmed cases of Lassa fever in Edo State from 1st January to 10th June, 2018 were entered into EXCEL spread sheet and analysed using and IBM SPSS version 21 [16]. One hundred and eighty-five cases were investigated during the period.Onset-to-intervention time was defined as the period (in days) from onset of illness to commencement of treatment with ribavirin. It was grouped (based on previous findings) into those who presented within 6 days of onset and those who presented after 6 days for treatment [14, 15]. Data was summarized with proportions and means. Relationship between socio-demographic variables and previous facility attendance with onset-to-intervention was evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Primary, secondary and tertiary education in Nigeria as used in this study is approximately equivalent to elementary school, high school and college education in developed countries. Association between onset-to-intervention time and outcome determined with chi square test. Level of significance was set at p< 0.05. Results were presented in tables and figures. Confidentiality and privacy of data was guaranteed by storing them in a protected and dedicated computer for the purpose.Two limitations of this study are worth mentioning. The first is that the subjects were a highly heterogeneous group especially with respect to age. Subjects’ ages ranged from less than 1 year to over 70 years. Secondly, the distances of the locations of onset of illness to the treatment facility were not captured. The study used the senatorial district of subjects as approximates of the distance to the treatment centre which is itself located in Edo Central senatorial district.

3. Results

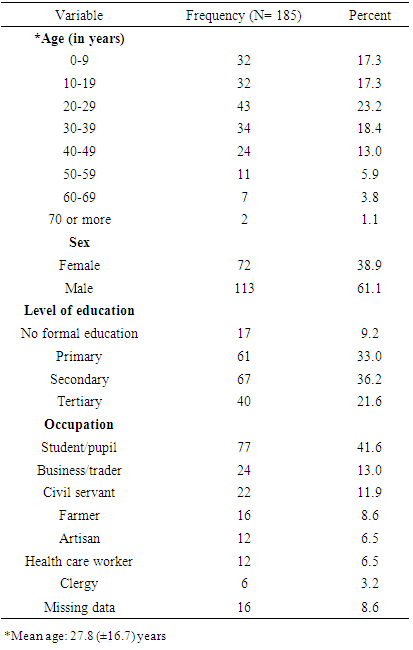

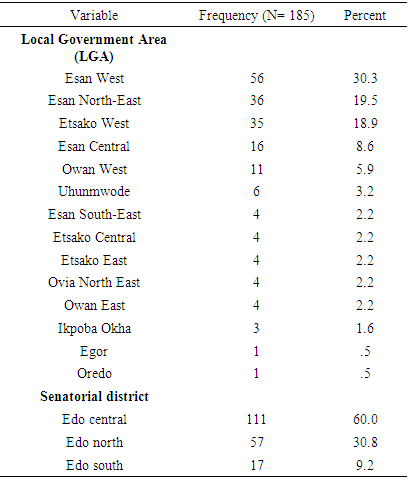

- Table 1 shows that the age group of 20-29 years was the most affected (23.2%) in this outbreak while the least were those aged 70 years and above. Mean age of cases was 27.8 (±16.7) years. More males (61.1%) and those with secondary level of education were affected. The largest occupational subgroup affected were students/pupils (41.6%). Six point five percent (6.5%) of cases were health care workers.

|

|

| Figure 1. Duration of onset of disease to time of intervention (isolation and treatment with ribavirin) |

|

| Figure 2. Outcome of Lassa fever (CFR: 14.6%) |

|

|

4. Discussion

- As noted in this study, almost a quarter (23.2%) of cases of Lassa fever in this outbreak was in the age group of 20-29 years alone while more than one-third of cases were children and teenagers. This observation where nearly half of those infected with Lassa fever were less than 30 years is of great demographic significance. This is in view of the fact that children on the one hand are prone to severe forms of infections due to under-developed immune system and on the other hand, young people are highly mobile and interact with large number of peers in schools, religious gatherings and other social interactions. Furthermore, children and young people constitute major parts of the human capital and are future of any nation [17, 18]. The proportion of lower age groups found in this study was higher than that reported for an earlier outbreak in Abakaliki [19]. However, there is no age predilection in those affected by the [20, 21]. Health workers were also affected in this outbreak. Though there was not enough information to guarantee that all of them were infected in the course of attending to patients, there is reasonable plausibility as Lassa fever has been known to occur as a nosocomial infection [11, 22]. Nosocomial cases of Lassa fever are fairly common in reported outbreaks with attendant adverse impact on the health care work force [23, 24]. In terms of distribution of cases by LGAs, Esan West had the highest number. The area, being part of Esan land, has been noted to have high prevalence of Lassa fever in previous reports [7, 25].Early presentation for definitive care was low among cases in this study. This may be due to a number of factors which includes delayed referral due to diagnostic uncertainties, poor index of suspicion among primary care providers, low levels of awareness or knowledge of Lassa fever in the general population and distance from the location of cases and referring facilities to the only available treatment centre in the State [26, 27]. This assertion is further strengthened given that well over one-third of those affected had history of prior clinical attendance or hospitalization at other health facility before presentation at the Lassa fever treatment center for testing and treatment. Lassa fever mimics other endemic conditions like malaria, typhoid fever and even respiratory tract infections with overlapping clinical features [11, 28]. Cases from Edo Central senatorial district had the shortest duration of onset-intervention time which is reflective of the advantage of having the treatment centre in the district. Early presentation of cases for treatment is critical to survival of Lassa fever patients as shown in this study. This is because of associated worsening morbidity with late presentation and the better efficacy of treatment with ribavirin when treatment is commenced within 6 days of onset of the disease [12, 14, 15]. The significantly higher proportion of survivors from the senatorial district (Edo Central) that host the Institute of Lassa Fever Research and Control Centre also supports the importance of the proximity of diagnostic and treatment centre to survival of Lassa fever cases.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

- The 2018 Lassa fever outbreak in Edo State had most of the cases from the known highly endemic areas of the state, that is, Esan land. Though only a small proportion of cases presented early at the treatment centre it improved survival of patients. In addition, proximity of cases to the only available diagnostic and treatment centre was significantly associated with survival. Efforts to improve community awareness and build capacity for quick referrals from primary care facilities should be sustained. It is also recommended that control efforts for Lassa fever should include longer-term plans to increase the number of diagnostic and treatment facilities in the State considering the high burden of disease in Edo State.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Osasu Imafidon, Wisdom William, Mohammed Ali and all Lassa fever surveillance team members in Edo State.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML