-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2017; 6(3): 58-66

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20170603.03

Assessing Undergraduate Students’ Sexual Practices, Perceptions of Risk and Sources of Information

Andrea Pusey Murray

Caribbean School of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Kingston, Jamaica

Correspondence to: Andrea Pusey Murray, Caribbean School of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Kingston, Jamaica.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The findings reported here form part of a larger research project that the main aim of this study was to survey the sexual practices and perceptions of risk among undergraduate students attending a tertiary institution in Jamaica. To answer the research questions, a cross-sectional survey research design was used. A total of 541 undergraduate students were selected using the stratified random sampling method. Data were collected through the use of a questionnaire and focus group discussion. The questionnaires data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics while the focus group data were analyzed using thematic analysis. The results showed that 66.4% of the respondents obtained most of their information on sexually transmitted infections from the mass media. More than half of the respondents (67.1%) used condoms during sexual activity and 52.6% stated that they have not changed risky behaviors despite concerns about Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). The Ministry of Health has instituted STIs campaigns and despite these campaigns the findings showed that only 32.7% of the respondents reported not using condom during sexual intercourse. The findings seem to suggest that there is still much to be done in terms of enlightenment campaigns, because of health hazards associated with risky sexual practices. Based on the findings and their implications the following recommendations were made: the Ministry of Health and the National Family Planning Board should be involved in campaigns that will target parents, schools and churches, to empower them with the tools that will help them to guide their children/relatives who are students about sexual practices and decision making.

Keywords: Behaviours, Communication, Information, Media, Parents, Sexual intercourse, Sexual practices, Sexually Transmitted infections, Perceptions of risk

Cite this paper: Andrea Pusey Murray, Assessing Undergraduate Students’ Sexual Practices, Perceptions of Risk and Sources of Information, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2017, pp. 58-66. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20170603.03.

1. Introduction

- Media coverage of HIV/AIDS is a fundamental part in the struggle against the disease. The importance of mass media in health promotion and disease prevention is well documented, since both routine exposure to and strategic use of mass media play a significant role in promoting awareness, increasing knowledge and changing health behaviors [1, 2]. Accordingly, mass media campaigns have been reliably linked to an increase in HIV/AIDS knowledge among individuals in low-income countries [3], including an awareness of HIV/AIDS, the ways in which the virus is transmitted, and preventive behaviors [4]. Knowledge is an important determinant in the pathways to changing health behaviors [5]. In the case of HIV/AIDS, a high level of awareness is likely to promote safe sex practices such as the regular use of condoms, which may reduce the prevalence rate of HIV infection [6, 7].The findings of two studies on HIV done in Nigeria, identified mass media as the predominant source of information for HIV/AIDS, STIs [8, 9]. According to Abdool Karim, and Meyer-Weitz [10] mass media campaigns utilizing television, radio, posters and billboards have been shown to be more effective for addressing specific issues. They have also been proven to be effective in increasing knowledge, improving self-efficacy to use condoms, influencing social norms, increasing the amount of interpersonal communication and raising awareness of health services [11].Today various sources provide young adults with information on sexual and reproductive health issues, including STIs. These sources include family, teachers, friends, health professionals, and the mass media [12-14]. Similar to studies conducted among college students in China and South Africa [15, 16], participants relied on the mass media (e.g. Internet, newspapers, magazines, television) as their main sources of HIV/STI information and their friends as discussion sources. Fennie and Laas, [17] conducted a study among 220 South African university students which revealed that 23% of the respondents noted that they have received HIV/AIDS information from peer educators and friends equally, teachers (22%) and parents/caregivers (18%). Associated literature such as in [18] found that adolescents without parental supervision are more likely to emerge in early sexual debut, increasing their vulnerability to HIV and STIs. This is in contrast with a study done by Dawood, Bhagwanjee, Govender, and Chohan, [19] who found that the preferred sources of information included television (84%) teachers (39%), friends (32%) and parents (28%). Key places to obtain sex information were indicated as the health centre (31%), the internet (21%), television (16%) and school/university (15%). A cross-sectional study conducted by Ajmal, Agha, Karim [20] among 957 undergraduate university students of Karachi, Pakistan reported that the four most common sources to acquire knowledge related to sex were friends (36.5%), internet/television (31.0%) and books (32.5%). Only 46.4% of the participants reported to ever talked with someone regarding sexual problems. Friends (42.0%) were the most common source to discuss sex issues.Pavlich [21] in their study reported that, only 46% of the participants received information on campus while 50% did not receive information on campus. Participants stated that they've received information from a variety of sources including college classes, residence halls or campus housing, student clubs and organizations, the Student Health Center, health fairs, pamphlets or brochures distributed on campus from a variety of sources, the university newspaper, and informal discussion with friends. The majority of respondents stated that they've received information from college classes and from pamphlets or brochures.In their own study, Kirby, Laris and Rolleri [22] who reviewed 83 evaluations of sex and HIV programmes that were based on a written curriculum and that were implemented among groups of youth in schools, clinics, and other community settings in both developed and developing countries, found that that the programmes resulted in a significant delay in sexual initiation. The programmes also reduced frequency of sexual intercourse among the youths and also decreased the number of sexual partners. The review found increases in perceived risk, improvement in measured values and attitudes, improved perception of the disease, as well as increased motivation to abstain from sexual intercourse or if not possible, restriction in the number of sex partners. In another systematic review of the research published on the impact of girls’ education on sexual behaviour and HIV in Eastern, Southern, and Central Africa.Parents are often hesitant to initiate conversations about sexual risk behavior and prevention of the spread of HIV/AIDS in part owing to perceptions that children are not ready to receive information about sexual issues [23] and lack of knowledge, skill, comfort, and confidence [24, 25] to have such discussions. DiIorio, Pluhar, and Belcher [26] claimed that many parents, however, either do not talk to their children about sex at all or have only limited communication on the topic. According to Petersen, Bhana and McKay [11], it is also possible that the older generation had not received any information on sex education, making it difficult for them to approach the issue as parents themselves. Furthermore, residential patterns and family structures might reduce the opportunity to discuss sensitive topics like sex. Geasler, Dannison, and Edlund [27] stated that although parents hope to do better the sexuality education they provide often resembles the level that they received from their own parents [28, 29]. Asante and Doku [30] found that only 27% of the students received information from their parents. Studies also have indicated that parents’ perceptions of their own sexual knowledge and comfort levels in talking about sexuality influence their communications about sexuality with their children [31, 32]. For example, Jaccard, Dittus, and Gordon [33] found that the two most important reservations mothers had about discussing sexuality with their adolescent were related to knowledge and comfort: fear that they would be asked something that they did not know and embarrassment when talking to their adolescent about sexuality. Further, parents who had received sexual health education, and presumably felt more knowledgeable and likely more comfortable talking about sexuality, were more likely to communicate with their children about sexuality [34]. According to Guilamo-Ramos, [35], teenagers appeared to be uncomfortable and embarrassed having conversations about sex with their mothers. They expressed fear of parental punishment and anger about the fact that they were sexually active.

2. Methods

- A cross-sectional survey research design was used which allowed for the utilizing of both qualitative and quantitative data collection and data analysis. According to Creswell [36], “in a cross-sectional survey research design, a researcher collects data at one point in time” (p. 389).Students who were used in this study were from the main campus and were selected using the stratified random proportionate method. The sample size was (n=541). A total of 33 participants agreed to participate by providing their contact information i.e. emails and telephone numbers. The researcher contacted the volunteers and explained verbally, the purpose of the invitation, their role and dates. From the 33 volunteers and the dates agreed upon, five focus groups were formed. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committees of the University of Technology, Jamaica.

3. Results

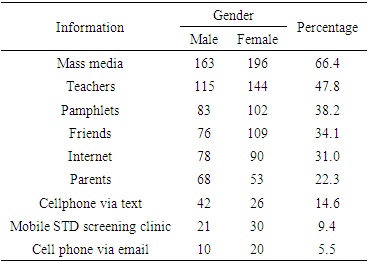

- Information on sexually transmitted infections. The participants were asked to indicate the medium from which they obtained information on sexually transmitted infections and were given options from which to select. As shown in Table 1 the most common medium through which the participants obtained information was the mass media.

|

4. Conclusions

- The mass media (TV and radio) were the most common medium the participants obtained information about sexually transmitted infections. The participants who have seen promotional advertisement on safe sex saw the Ministry of Health promotional campaigns, displays on public transportation, and murals on the walls of some communities. Both male and female participants felt strongly that the government should be seeking ways to improve the effectiveness of the STI campaigns. It is a public health imperative that if incorporated successfully demonstrated strategies from past prevention efforts into current undergraduate students STI/HIV prevention programmes and that we also continue to be innovative in ways to protect the undergraduates, as well as teach them to protect themselves, from STI/HIV infections. This could be included in their curriculum and information passed on during academic advisement sessions. When parents converse openly with their son or daughter about sex, relationships, and how to prevent HIV, STDs, and pregnancy, they can help promote their child/children's health and reduce the chances that they will engage in risky sexual behaviors that place them at risk.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML