-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2017; 6(3): 50-57

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20170603.02

Spanning the Ages: Intergenerational Mentoring for L.I.F.E.

Gregory Clare1, Aditya Jayadas1, Janice Hermann2, Emily Roberts1

1Design, Housing & Merchandising, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, U.S.A.

2Human Nutritional Sciences, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, U.S.A.

Correspondence to: Gregory Clare, Design, Housing & Merchandising, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, U.S.A..

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The population is aging. With aging, it is vital to look for opportunities to improve health and stay engaged. Individuals can stay engaged in life in a number of ways, including maintaining independence, physical and mental fitness, and social engagement, all part of active aging. An Active Aging for L.I.F.E. four-part series on: longevity, independence, fitness, and engagement were offered for participants at a Midwestern University comprising college students and older adults. A series of follow-up focus groups took place 6 months after the Active Aging for L.I.F.E. program in order to explore the effects of combining different age groups who may have viewed the series information from different perspectives based on their life-stage. Several shared dimensions emerged from the coded data between the older and younger adults including coping, lifestyles, relationships, new knowledge, and communities as important predictors of healthy aging.

Keywords: Active Aging, Community Education, Mentoring, Proactive Coping

Cite this paper: Gregory Clare, Aditya Jayadas, Janice Hermann, Emily Roberts, Spanning the Ages: Intergenerational Mentoring for L.I.F.E., International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2017, pp. 50-57. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20170603.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The inevitability of aging does not preclude an opportunity for meaningful preparation to improve our experience through knowledge sharing with others. The changes in demographic trends globally towards an aging population facing the risks of spiraling healthcare costs, housing needs, economic security, and supporting well-being throughout the aging process suggest the need for new approaches to community education programs. One approach includes using educational institutions that are embedded in communities to offer programs to local stakeholders to support positive behavior change. For Land Grant institutions, the reach and impact of community education programs may be supported through Cooperative Extension partnerships. The involvement of community partners such as senior centers, counseling centers, libraries and schools similarly may offer potential participants for community education speaker series programs. Universities offer multiple resources to support public education including aging-related content knowledge professionals, meeting rooms, and other needed equipment to support a favorable environment for support and learning. Successful models of community engagement in the future will require scaling for delivery in diverse communities, inner cities, or other targeted urban and rural geographic locations. Prior to developing a diverse community program of global aging education, a program’s benefits and opportunities to meet the needs of different audiences must be better understood. In 2016, a pilot community speaker series on the concept of active aging was conducted at a large Midwestern university. Active aging involves staying engaged in life in a number of ways, including maintaining independence, physical and mental fitness, and social engagement. The Active Aging for L.I.F.E four-part series addressed the four domains of longevity, independence, fitness, and engagement for program participants including college students age 18-25 and older adults age 65+. Using focus group research to measure the effects of the Active Aging for L.I.F.E. speaker series on participants from the two age groups, the goal of the researchers is to refine the approaches and content of the community engagement program.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intergenerational Community Health Education Programs

- Engaging members of communities for behavior change has received substantial attention in the academic literature. Demographic changes globally highlight the need to address the anticipated behaviors of older adults which influence the aging process in general. Research has suggested that intergenerational interactions improve when the goals of community programming are designed to be social in nature [1]. Knowledge sharing of context-specific experiences may help prepare younger participants for what to expect while aging and for older adults to employ new strategies for ameliorating the aging process from younger people’s insights.The goal of community programs facilitating intergenerational interactions must be well designed, content rich, and focused on increasing the competency of individuals to cope with the aging process [2]. Combining social interaction with relevant content during community programs may help to strengthen intergenerational relationships. Hegeman et al. found that goal-oriented programs in which attendees work together for the good of the community may predict probable outcomes when programs are well designed and measure anticipated outcomes upon individuals’ behaviors [3]. Another important goal of community health education is to facilitate attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that contribute to healthier lifestyles across the life-span. Whether the solutions of community programs focus on reducing maladaptive behaviors or increasing adaptive behavioral responses, the underlying assumptions of promoting healthy behaviors remains a key priority. Positive program content combined with achievable coping strategy is proposed to strengthen participant outcomes. Exposing younger people to older adults and learning the barriers to healthy lifestyles may support attitude change and facilitate positive behavior change in a prosocial manner. Increasing the empathic connections of younger participants to the experiences of older adults may also provide corollary benefits in communities. Positive behavior change has been demonstrated in caregiving initiatives designed to educate younger persons about the physical needs of older adults which may predict behavior as the students’ age [4-6].

2.2. Intergenerational Community Health Education Programs

- Mentoring offers similar benefits in intergenerational programs where knowledge gaps may be reduced among older and younger people. For example, younger people may possess greater experience in the emerging technologies and share skills with older adults, while older adults can offer suggestions about maintaining interpersonal relationships based on their years of experience. Positive benefits of mentoring programs were found at a large South-western university where the depth of learning about aging occurred through reflective journals and on ongoing meetings supporting the intergenerational relationships [7]. Mentoring relationships at the community level are contingent upon trust and guidance within mentoring cohorts. The relationship between universities and community agencies may help to support these critical processes during the formulation of new intergenerational mentoring relationships contingent on local traditions, support, reputation and available resources. Research has suggested that in Western countries, undergraduate students possess more positive attitudes about aging; however, education programs are needed to counter the effects of cultural stereotypes and demographic trends [8]. Exchanging information based on the life experiences of older and younger adults is predicated on many factors including socialization, internalization, externalization, and combination of new knowledge [9]. Years of experience may also offer older people an opportunity to share tactics and strategies that younger persons should avoid during the aging process. We believe that successful mentoring is not unidirectional in nature and meaningful tacit or procedural knowledge may be shared between intergenerational cohorts supporting positive behavior change. The key to achieving this goal is creating an effective two-way channel of communication and framework for the experiential knowledge to flow between persons of different generations. Community sponsored intergenerational learning programs which facilitate interactions between people who might otherwise not interact outside the family structure and may offer benefits to reduce the stereotypes of aging which are reinforced in popular culture. In addition, the benefits of moving from attitude formation to behavior change concerning the aging process may help to preserve knowledge which might otherwise be lost through over-identification and stereotypical alignment within generational groups, or cohort-centrism as the phenomenon has been described [10]. Modalities supporting active aging processes as opposed to viewing the inevitability of aging as something affecting others highlight a possible major benefit of intergenerational mentoring knowledge sharing programs in communities. Aging is occurring whether we attempt to deny it, shame the process, or attempt to avoid the process altogether during our younger years. Supporting positive behavior change while increase intergenerational sensitivity to aging-related issues through mentoring are key priorities of community education programming.

3. Methods

3.1. Focus Group Design and Procedures

- A semi-structured questionnaire was developed as a follow-up to an aging LIFE (Longevity, Independence, Fitness, and Engagement) speaker series conducted over four consecutive weeks. Focus groups were administered six months after the speaker series concluded. Focus group participants were recruited based on their attendance during all four sessions of the prior speaker series. All the testing protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the university.Each focus group session lasted one hour and consisted of four to six participants. The sessions were conducted in the afternoon and evening hours for the younger participants, and during the evening hours for the older participants based on their availability. The focus group sessions were facilitated by four (two males and two female) faculty members with training in conducting focus groups. A printed interview guide was used to maintain consistency among the researchers during the focus groups. Probes were used for responses that needed clarity and to evoke greater contextual depth. The facilitators ensured that each participant was engaged by prompting all the participants for responses. Each session was audio-taped and transcribed by the facilitators. The facilitators also took notes as the participants responded to questions. There were nine questions posed to each participant, six of which are relevant to this paper and presented in Table 1.

|

4. Data Analysis

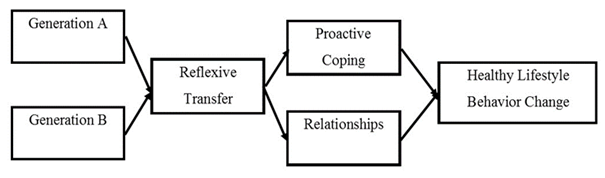

- Verbatim transcripts were created to evaluate participant responses. The transcripts of all six focus group sessions consisted of 21,725 words and 1,542, lines of text. Content analysis was used to analyze the data. The unit of analysis was text from audio recordings that were transcribed from the six focus group sessions. The text was then coded using first and second cycle coding. Attribute coding was used to create notations including participant demographics and themes, which were generated from the second cycle coding. Specifically, pattern coding was used as part of the second cycle coding to generate themes. This was achieved by two researchers reviewing each of the six focus group transcripts separately to identify emergent themes. The researchers independently identified themes from a review of the transcripts. Following this, through discussion, three main themes were identified, with sub-themes under each theme. Next, two researchers reviewed each of the transcripts and coded them for the three themes and sub-themes. The two researchers then met to discuss the initial coding results. The text from each researcher cohort was read through several times to gain an understanding of the context as it relates to the L.I.F.E. series. The final cross-cohort coding was developed through consensus of the researcher after discussing each recurring theme and sub-theme generated by the two-researcher cohorts. Lastly, the most salient quotes for each age group representing each sub-theme were included in the manuscript. The conceptual model describing the evolving themes supporting behavior change in aging emerging from the speaker series is presented in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer Influencing Healthy Lifestyle Behavior Change |

5. Results

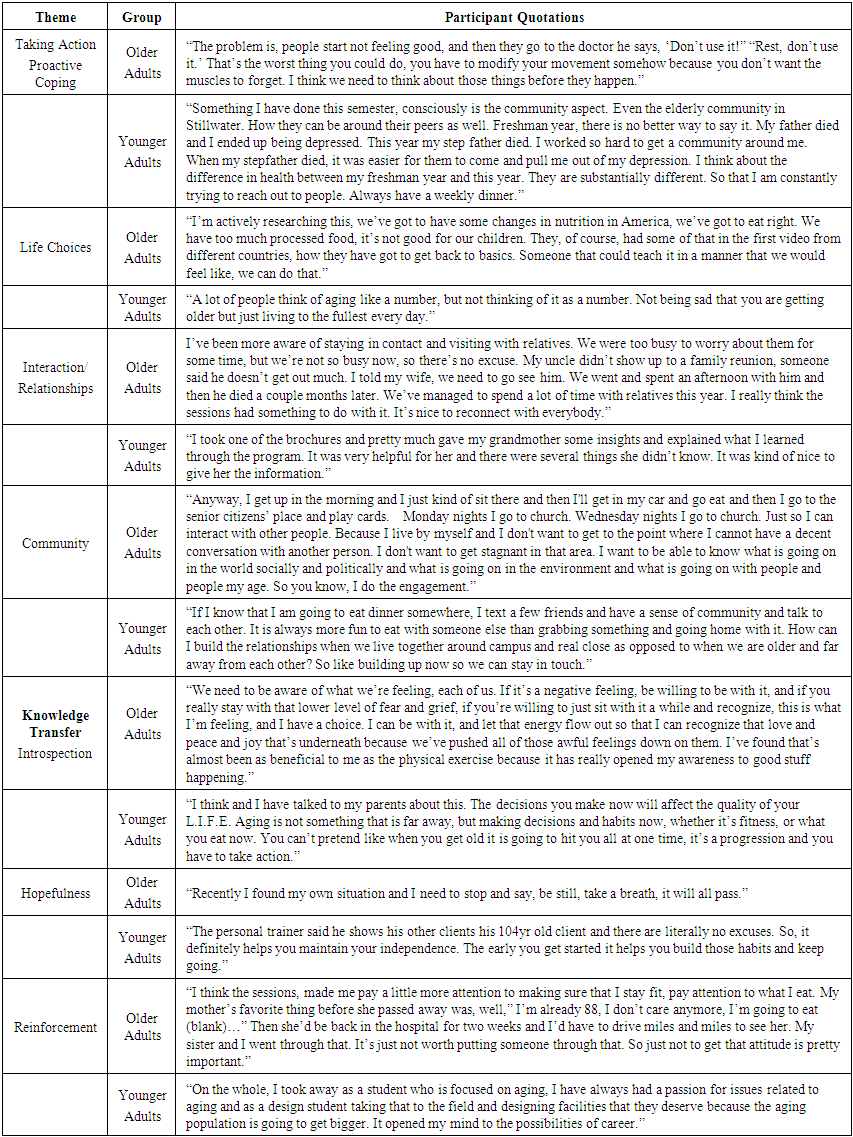

- A total of 18 older adults age 65+ and 12 younger adults age 18-25 participated in the focus groups. The older adults’ demographics were 11 females and 7 males and the younger adult participants were 11 females and one male. All participants were Caucasian except one African-American woman in the older adult group and one African-American woman in the younger adult group. The results from the six focus group sessions using illustrative quotations from the two age groups for the different themes identified are summarized in Table 2.

| Table 2. Focus Group Semi-Structured Interview Guide |

5.1. Theme: Taking Action

- This theme has to do with making choices and acting upon them. The action theme involved two sub-themes, namely ‘proactive coping’ and ‘life choices’. Both younger and older participants used different strategies to cope and make choices that could be measured in the context of observable behaviors.

5.2. Sub-Theme: Proactive Coping

- Older adults routinely shared their personal experiences about aging during the focus groups, and frequently shared strategies to avoid negative outcomes. One common experiential thread shared among older participants included the importance of understanding one’s current capabilities and limitations. Based on the current state perspective, they shared proactive steps that if acted upon could improve wellbeing in their current and future lives. Proactive coping is defined as a person’s ability to anticipate future outcomes based on current evidence or information that they possess and applying adaptive responses to reduce negative outcomes. Proactive coping strategies have been demonstrated to have a direct positive relationship to adaptive protection motivations when people interpret health communications that are framed in a positive manner and for which self-efficacy or the willingness and ability to adapt to risks are highlighted in communications [11]. For example, if a doctor or a relative told the older adult they should limit physical activity like walking, suggestions were offered that exercises, while seated, could support muscle stimulation as an alternative. A study by Sohl & Moyer found that proactive coping behavior is mediated by two proactive coping factors; using available resources and realistic goal setting to achieve desirable results [12].For younger participants, proactive coping strategies were similar in that participants discussed mitigating behavioral alternatives like the need to start a jogging program instead of maintaining a current rigorous exercise program at the gym rather than quitting exercise altogether. Another proactive coping dimension highlighted the recognition among younger participants that if a person does not socialize and isolates themselves then sadness and clinical depression may develop. Proactively, some of the younger participants acknowledged the risks in their current lives from social isolation due to various environmental factors and identified steps they had taken since the speaker series to improve their social interactions. The individual’s belief and optimism that they are in control of their aging process and have the ability to change outcomes been demonstrated in various studies [12, 13]. The importance among both groups for sharing meals as a favorable proactive strategy to decrease perceived social isolation and depression was highlighted. Training programs aimed at increasing coping knowledge to stimulate behavior change have found significant differences between pre and post-test survey data measuring behavioral interventions [14]. Grounding the approach with information exchange for normative behaviors of individuals in different age groups may simultaneously increase participant knowledge and empathy among groups for aging coping strategies.

5.3. Sub-Theme: Life Choices

- Taking steps now to change behaviors and health outcomes such as obesity and disease progression were important considerations to both older and younger participants. According to the American Journal of Medicine, several factors may contribute to healthy lifestyles intergenerationally including body mass index, physical activity, smoking cessation, healthy nutrition, and moderate alcohol use [15]. Both older and younger participants acknowledged the fact that healthy life choices supported by good nutrition, exercise, and social interaction were important for health and wellbeing. However, the older participants pointed out that it was important to learn about choices that could be adapted to their current age and physical status. A study conducted over three years using an intergenerational approach focused on delivering content that would help individuals make incremental lifestyle changes to improve individual health [16]. Younger participants believed that through adopting healthy life choices, and avoiding unhealthy ones shared by the older participants, that they could improve both their present and future health status.

5.4. Theme: Interaction

- The reciprocal act of communicating or being with others was valued by both younger and older participants. This theme was further broken down into “relationships” and “community.” Both sub-themes were important, especially in older individuals. Older participants noted that younger people are frequently focused on their busy lives and the time spent communicating in face to face interactions with low levels of distraction is often difficult. The strong presence afforded by the speaker series made the older adults’ feel like they were appreciated and that their voices were heard. Similarly, the younger people acknowledged that they often feel too busy to take time to communicate with and understand the needs and challenges of their older family members and the speaker series provided a rich environment for learning about the challenges that older adults may face.

5.5. Sub-Theme: Relationships

- The opportunity to form new relationships was important to both younger and older participants. Older individuals reflected on how not having time earlier in life resulted in not being able to maintain relationships. With more time on their hands, older individuals were willing to make the extra effort to meet an old friend, relative, or seek new friends. Spending time with grandchildren was also especially important to some of the older participants who share in nurturing these family members. As for younger individuals, participating in the LIFE series reinforced the importance of relationships with both family and friends. Younger participants reported sharing some of the knowledge that they had gained from the LIFE series with their parents, grandparents, and other close-ties. Intergenerational interactions during an active aging speaker series may facilitate solidarity between both groups simultaneously through increased empathy and decreased intergenerational ambivalence [17].

5.6. Sub-Theme: Community

- The community sub-theme of improving relationships offered different definitions of the term “community” for older and younger participants. The older participants viewed going to church and community centers to interact with older individuals as important forms of social support. For younger individuals interacting with friends, volunteering and going out for meals helped define a “community”. Whether described as organized social structures or individually generated communities of important others the value of remaining engaged in either situation was highlighted. Cognitive decline in aging may be reduced through increased social interactions and group engagement across age groups [18]. For older adults, the benefits of engagement to reduce loneliness and social isolation have received positive support [19]. For younger adults, data suggests that social engagement including volunteer work, social cause support, and other ways of giving back help to validate the self-image [20]. Likewise, pedagogical approaches designed to reinforce speaker series objectives including providing a suitable environment for social interaction, speaker and learner activities, varied topics and delivery methods, and discussion have been demonstrated to facilitate inter-generational service learning to support lifestyle change [2]. Student exposure to healthy aging strategies during formal education may influence lifestyle and vocational choices that shape future outcomes to some degree, but more study is required.

5.7. Theme: Knowledge Sharing and Introspection

- Knowledge sharing was an important theme for both younger and older participants. The older participants reflected on feelings and emotions that they experience in their day-to-day life and explained how they act on those feelings. Older participants compared the process of reflecting and sharing experiential information as important a daily activity as physical exercise for supporting personal wellbeing. The younger participants, on the other hand, drew from experiences encountered with their parents and grandparents. The role of thinking about aging in new ways and sharing positive thoughts about a future that they expect as they age was rewarding for the younger participants.

5.8. Sub-Theme: Hopefulness

- The sub-theme of knowledge sharing was the most prominent among the three sub-themes. The older participants reflected on being hopeful for the future and living life to the fullest in spite of physical challenges. They reflected on not letting the current situations they are dealing with have a negative impact on their lives and choices by maintaining a positive outlook. Their hopefulness was recognized through their understanding that they may need to slow down during some daily activities, breathing and taking time to acknowledge that the challenges “will pass.” The younger participants, on the other hand, perceived hopefulness as “there’s still time to fix my lifestyle now and become a healthy older individual.” Seeing and hearing from the older participants in the L.I.F.E. sessions that it is possible through behavioral changes to lead healthy and happy lives longer supported younger participants’ hopefulness for their future (older) selves.

5.9. Sub-Theme: Reinforcement

- The sub-theme of knowledge sharing called reinforcement emphasized the importance of the L.I.F.E. series talks on longevity, independence, fitness and engagement. Both younger and older participants pointed out that attending the active aging sessions reinforced key concepts involved in the aging process which must be considered and addressed. The primary concerns for both groups emphasized the need for regular exercise, socializing with others and maintaining a healthy diet. From the students’ perspective, learning more about the factors influencing the aging process stimulated perceived career opportunities for supporting the aging population. The action-oriented behavior change content reinforced the need for community members to work together to address future challenges.

6. Discussion

- The intergenerational relationships offered in community environments such as universities may facilitate respect and candor between generational cohorts that is difficult to achieve in nuclear families bound by grandparents, parents, children, and grandchildren as members. Family members must attempt to balance a generational and family hierarchy when considering the process of aging. Observing family members aging over time is arguably different than casual interactions with older or younger persons during a speaker series. Informal and temporary mentoring relationships supported by community education programs may be valuable for reducing stigmas of aging by facilitating proactive behavior change. The researchers discovered from the focus groups, the benefits of social interactions during educational programming supporting Morita & Kobayashi [1]. The researchers also found some evidence that participants’ informal relationships increased the competency and skills for coping with the aging process [2]. Community-based speaker series support a relatively risk-free environment for exchanging ideas. Speaker series participants may proceed from being mere strangers at the beginning of the series to familiar members of a learning community by its end. Information sharing is likely to include reflections on participants’ personal and family experiences. Intergenerational group dynamics may support the formulation of novel solutions to problems that could be more difficult than those achieved in nuclear families. This phenomenon has been described in the intergroup helping literature as in-group (family) and out-group (community) relationships [21]. Generally, people support in-group helping behavior when communications are framed for action; however, researchers suggest that the motivation to provide help when communications were values based supports out-group helping behavior [22]. Rich personal information shared during community education programs is framed in both action and values contexts should be studied further. The role of intergenerational aging speaker series may offer opportunities for increased empathy, as participants learn approaches that others use in their own lives or while coping with families. While clearly, each generational group processed the speakers’ series information in different ways, an emerging benefit was the participants’ goal orientation to take action to improve their life conditions. The combination of participants’ reflections impacted both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations to improve the aging process. Intrinsic motivations were expressed through the emerging dimensions for the benefits to the individual of sharing knowledge, strengthening coping skills, forming new relationships, and developing a sense of community to support positive lifestyle changes. The exchanges between participants were routinely positive and focused on a sense of “hopefulness” about aging. This finding supports the relationship between hopefulness and finding solutions found by Hegeman [3]. Similarly, when participants uncovered potential solutions for healthy aging, they maintained an action orientation to address the issues supporting both reactive and proactive coping strategies. The emerging theme called “taking action” took different forms for proposed participants’ solutions. For older participants who frequently shared their aging-related challenges, advice from both younger and older peers included reactive coping strategies to improve the immediate challenges. Examples included how family members are coping or have coped with similar challenges. However, when older persons shared their challenging experiences with younger members, they often suggested proactive coping strategies to avoid similar pitfalls as the younger person aged. Younger participants acknowledged that they need to take action now to reduce the risk of similar outcomes shared by the older participants. This study provides some evidence supporting Eppright et al. [23] that communication strategies to avoid negative outcomes in a proactive manner is an effective predictor of adaptive protection motivations.

7. Conclusions

- Topical content of an intergenerational active aging speaker series designed to improve health indicators and outcomes across the lifespan will require cross-sectional data that explores the individual, families and supporting communities within the context of the home, day-to-day physical and mental activities of individuals. Prior to determining an effective system for improving active aging education programs, more research into homogeneous group responses to aging content is required along with the role of intergenerational effects of knowledge sharing approaches. Speaker series attendees’ knowledge sharing after the speaker series with close and loose-ties both personally and professionally stimulates community word of mouth network communication effects for positive behavior change. This study provided pilot evidence supporting an intergenerational approach to sharing information supporting healthy aging across the lifespan. The limitations of the study included risks to replicability and generalizability of positive behavior change outside of the context of an incentivized community education program. The role of incentives provided at both the end of the speaker series and focus groups may have influenced more favorable behavioral outcomes than would be possible in their absence. However, the researchers view this risk as relatively low due to the fact that behavior changes discussed in the focus groups occurred six months after the speaker series. There is a need for studying the longitudinal effects of aging education among a diverse sample population. The authors believe that intergenerational mentoring which serves as a primer for more thoughtful lifestyle choices throughout the lifespan may provide an ideal model for reducing risks for an aging population. Community education programs which facilitate informal intergenerational mentoring also build awareness that time is passing and the inevitable challenges related to aging will ultimately confront the younger generations as they move through the life course. Increased exposure to what to expect in the aging process and ways to combat these challenges and barriers to well-being may be achieved through community programming similar to the Active Aging for L.I.F.E. series and may support risk reduction and intergenerational bonds across the lifespan.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The researchers wish to acknowledge the College of Human Sciences at Oklahoma State University for funding this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML