-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2015; 4(2): 29-33

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20150402.02

Prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen among Residents of Julius Berger Staff Quarters, Kubwa, Abuja

Joyce M. Terwase, Chima K. Emeka

Department of Psychology, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Joyce M. Terwase, Department of Psychology, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

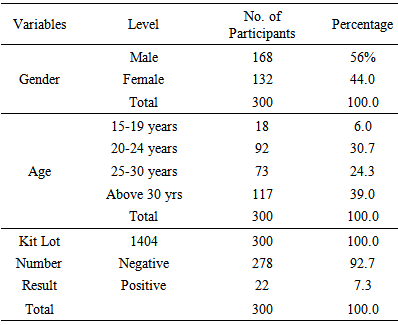

This study determined the Hepatitis B surface Antigen (HBsAg) as a serological marker for the viral infection between male and female residents and among various age groups of Julius Berger staff quarters Kubwa Abuja. An immunochromatographic Skytec® HBsAg test strips (manufactured by skytec diagnostics USA) and Alere chase buffer (manufactured by Alere LTD, UK) designed for the qualitative detection of HBsAg in serum was used to screen for the virus among 300 participants that were purposefully selected. The overall seroprevalence of HBsAg in the study population was 7.3%. Although, HbsAg was detected at a higher rate in males than females and the differences was statistically significant (P <0.05). However, among various age groups of 15-19,20-24,25-29 and above 30 years, the difference was not statistically significant (P <0.05). The HBsAg prevalence in this study shows intermediate endemicity which implies that everybody is at risk. Therefore, every individual should be screened routinely and not based on risk factors in order to identify those who will require treatment and vaccination against hepatitis B virus infection.

Keywords: Prevalence, Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg), Julius Berger staff quarters

Cite this paper: Joyce M. Terwase, Chima K. Emeka, Prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen among Residents of Julius Berger Staff Quarters, Kubwa, Abuja, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2015, pp. 29-33. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20150402.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Hepatitis B is a major global health problem, it is a potentially life-threatening liver infection caused by Hepatitis B virus (HBV). Hepatitis B virus is 50 to 100 times more infectious than HIV [31]. Recent statistics indicate that not less than 23 million Nigerians are estimated to be infected with the Hepatitis B virus (HBV), making Nigeria one of the countries with the highest incidence of HBV infection in the world [31]. Consequently, the global disease burden of HBV was considered substantial due to the high HBV related morbidity and mortality [28]. Approximately 5.0% of the world’s populations were reportedly seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg [29]. The global burden of hepatitis B remains enormous, due largely to lack of universal HBV vaccination 30]. Studies done in Nigeria shows HBV carriage rate in the range of 9 to 39% [1]. It has been estimated that 19 million people have been infected (About 1 out of 10 people). More than 3 million people are chronically infected 7.3- 24% (Average 13.4%) of the population has serological evidence of current infection [2]. Results further reveal that, over a 100,000 people will become infected each year and 5,000 will die each year from hepatitis and its complications. Approximately one health care worker dies each day from hepatitis [3]. The psychological impact of hepatitis B virus infection does not only pose a threat to the nation but everybody is either infected or affected. An infected individual faces psychological issues ranging from increase in financial burden, unproductivity, loss of life and stigmatization. The individual may experience extreme stress, anger, depression, fear, confusion, guilt, hopelessness, anxiety, loss of status, difficulty in disclosure etc. The impact is very severe with consequent implications on the affected people and the nation as a whole. This study tends to establish the prevalence of HbsAg in Julius Bergrer staff residential quarter Kubwa Abuja due to some predisposing factors observed in the environ. Some of the risk factors include; high prostitution/sex work activities observed at high spot areas within Kubwa community, clustering and overcrowding of passengers in the official company transportation vehicle conveying resident workers to the site of construction daily. Also, close personal contact is a characteristic seen among most residents that stay in a single room which accommodates over six people in the same room. From the foregoing therefore, two hypotheses were raised and tested for the study:i. There is a significant difference between male and female residents of Julius Berger Camp, Kubwa, Abuja on the prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen.ii. There is significant difference among different age groups of Julius Berger Camp Kubwa, Abuja on the prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen.

2. Methods

- The methods here focus on the methods of research that was adopted for this study. The research design adopted for the study was the ex post factor design. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data.

2.1. Participants and Procedure

- Exactly 300 participants took part in this study. This comprises both male and female residents of Julius Berger staff quarters Kubwa, Abuja. They were purposively sampled because the researchers only tested residents that were available and willing to participate at the time of the visit and also for the reason that the respondents could only be found in one location. The researchers approached these participants and intimated them about the study, and one of the researchers being a Professional laboratory technologist specializing in physiology/pharmacology technology, they accepted and consented by filling the informed consent forms, although others refused to take part in the study, for the reason of time and convenience, and even fear of discovery. Those participants who accepted were then grouped into the following age grades 15-19, 20-24, 25-30, and above 30 years old. The required data for the study was collected from residents of Julius Berger staff quarters kubwa, Abuja through the collection of blood samples and this was made easy using finger pricks (lancet), as it is almost painless and the risk of refusal is minimized. Laboratory test is conducted on collected blood samples using HBsAg test strips to detect presence of HBsAg in the human blood. Samples that had the presence of HBsAg were labelled reactive (positive) and those samples that did not have the presence of HBsAg were labeled Non-reactive (Negative) and the results were recorded in the research work sheet. The entire exercise lasted for two days and was stationed in the club house situated inside the quarters which is central in accessibility to all the residents of Julius Berger staff quarters Kubwa, Abuja.

3. Instruments

- The instruments used in this study includes methylated spirit used for disinfection of the skin, lancet for pricking of finger, cotton wool, skytec HBsAg test strips and Alere chase buffer which are immunochromatographic and qualitative in nature is used to detect the presence of HBsAg in human blood and read in-vitro. A self-designed HBsAg worksheet was used to collect data for the study.

3.1. Results

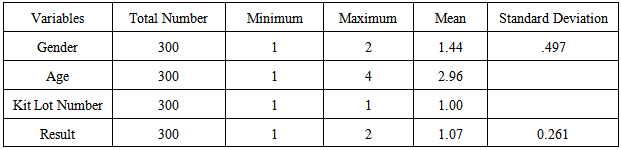

3.2. Table 2: Mean and Standard Deviation of the Variables

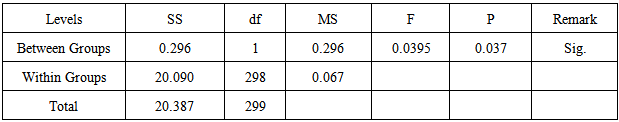

3.3. Table 3: Summary Table of One Way ANOVA Showing the Difference between Male and Female Residents of Julius Berger Camp, Kubwa Abuja on the Prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen

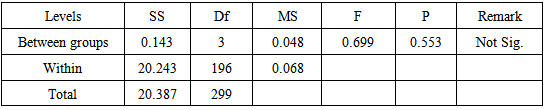

3.4. Table 4: Summary Table of One Way ANOVA Showing the Difference among Different Age Groups of Residents of Julius Berger Camp Kubwa, Abuja on the Prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen

3.5. Discussion

- From the result that was got, there is a significant difference between male and female residents of Julius Berger Camp, Kubwa, Abuja on the prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen F (1,298) = 4.395; P < 0.05 which is consistent with the stated Hypothesis of the study. Some of the reasons for the high infection rate among the males may be due to habits such as multiple sexual partnership and polygamy which may be higher among the males. It was found in some studies [4], [5] in Gombe and Jos respectively that having multiple sexual partners increased the carriage of HBsAg. This is expected as being male is known to have high risk of serum hepatitis infection [6]. Alcohol consumption, tattooing, circumcision could also be a possible reason for prevalence amongst the males.This observation however, is in line with the previous report [7] in which males had higher prevalence rate than females in both rural and urban areas with observation that male sex was an important risk factor for HBsAg positivity. A report in another study [8] reported higher prevalence of HBsAg among males than females in Lagos, Nigeria. A similar study also reported a higher HBsAg seroprevalence in males than females among patients attending Dental Clinic at the University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan and this was due to shorter HBsAg carrier rate in females than males [9], [10] Similar findings were also reported in a study among HIV infected patients in Jos, Nigeria in which higher HBV prevalence in males was reported [11].However, this finding is in contrast to what was reported that males and females did not differ significantly in HBsAg seropositivity [12]. The reason for this difference might be attributed to the differences in population selection which is seen by a larger number of male participants used in this study. It is also observed that more males than females subjected themselves voluntarily to testing especially amongst residents, this suggested that both sexes were equally susceptible to HBV infection and that gender might not necessarily be an important epidemiological determinant of HBV infection among the study patients.Generally, overall seroprevalence level of 7.3% in this study is in conformity with the established fact that HBsAg is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa region [13]. The classification of high endemicity from HBV infection has been defined as HBsAg greater than 7% in an adult population [14]. This value of 7.3% HBsAg prevalence reported in the study is lower than the 20.0% reported in another study [16], also among prospective blood donors in Otukpo, an urban area of Benue State; the 14.5% reported [10] among blood donors in Ibadan and the 14.5% reported in Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH) [17]; is similar to reports from Makurdi among pregnant women [18]. However, the result (7.3%) is higher than the 2.1% prevalence reported from a similar study in Port Harcourt among University students [19].Also from the result gotten, there is no significant difference among different age groups of Julius Berger Camp Kubwa, Abuja on the prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen F (3, 296) =0.699; P <0.05 which is not consistent with hypothesis 2 of the study. This is in accordance to a report [20], that age was not significantly associated with HBsAg seropositivity among Afro-descendant community in Brazil. The reason may be due to the fact that most of the participants fall within the age range of greatest sexual activity thus supporting the role of sex in the viral transmission. However, it is also very possible that other than HIV, many people may not be aware of other sexually transmitted viral infections and so continue to have unprotected sex with fellow HIV/AIDS negative partners who might be chronic carriers of HBV. It has been noted that in Africa more than half of the population become HBV infected during their life time and about 8% of inhabitants become chronic carriers. The prevalence of seropositivity could be associated with sexual activity and intravenous drug use among Nigerians in their third decade of life as it has been reported that, there is an unprecedented rise in the number of intravenous drug users especially among students of secondary and tertiary institutions in central Nigeria [21].In addition, the various age groups are equally exposed to HBV irrespective of their age differences due to the fact that same predisposing factors of overcrowding and clustering is a characteristic seen in their vicinity and their daily life. A different study found a significantly higher HBsAg prevalence among prisoners in eastern Nigeria, which was attributed to overcrowding and clustering [22]. Also, the almost same prevalence rate of HBV among the age groups in this study indicates that most of these subjects may have acquired the infection through sex and transfusion of unscreened infected blood while others may have acquired any of these infections prior to transfusion [10]. Some researchers have observed that among the sexually transmitted and blood borne infections, there is a higher probability of getting infected with HBV than the others because of its low infectious dose [14].However, the finding in this study is in contrast to a similar study [4], which noted that the highest rate of HBsAg seropositivity was in the older age group. Also, another study [23] reported higher HBV prevalence among older age group (30-34 years), while yet a similar research [24] found HBV prevalence to be highest among blood donors aged 18 to 27 years old, the most sexually active age group. However, the age of acquiring infection is the major determinant of the incidence and prevalence rates [25]. Again serological evidence of previous HBV infections varies depending on age [12]. Studies have shown that, the likelihood of chronicity after acute HBV Surface Antigen, which may lead to hepatitis B viral infection, varies as a function of age in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised host [26]. A research studying 213 children with sickle cell anaemia, showed that markers of HBV infection (HBsAg and anti HBc) increased with age [27].

3.6. Implications of the Study

- The findings in this study imply that all persons who are hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive are potentially infectious. The many millions of people around the world who become HBV carriers are a constant source of new infection for those who have never contracted the virus. The increasing number of HBsAg positive persons will certainly have a negative impact on the productivity and efficiency of the individual and the country at large. These findings will aid in Provision of most recent baseline data for planning and monitoring of National Health Programs by health managers.In addition, these findings also have implication for healthcare professionals such as medical doctors, psychologists, clinical psychologists, nurses, health managers etc. This will enable them advance appropriate interventions for positive individuals.

4. Conclusions

- This study revealed an overall prevalence of HBsAg to be 7.3% (n = 300) among the residents of Julius Berger staff quarters Kubwa, Abuja. It also shows that highest prevalence of HBV infection was observed among males than the females while there were no significant differences among the various age groups. This study however, confirmed that every person is at risk of hepatitis B infection irrespective of age or gender.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML