-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2014; 3(1): 1-7

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20140301.01

Herpes Simplex Virus-2 Sero-testing among Individuals Presenting for HIV Counselling and Testing in a Centre in Nigeria

Bamidele Oke 1, Sunday Omilabu 2, Nkiru Odunukwe 1, Oliver Ezechi 1, Olumuyiwa Salu 1, Rosemary Okoye 1, Olufunto Kalejaiye 1, Nkiruka David 1, Azeez Anjorin 3, Adesegun Adesesan 1, Babatunde James 2, Remilekun Orenolu 2, Adebukola Adetunji 1, Dave Oladele 1, Jane Okwuzu 1

1Nigerian Institute of Medical Research

2College of Medicine, University of Lagos

3Lagos State University, Microbiology

Correspondence to: Bamidele Oke , Nigerian Institute of Medical Research.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

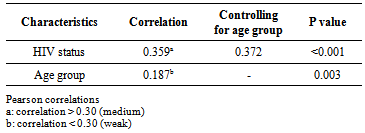

Herpes Simplex Virus-2 (HSV-2) as an ulcerative mucocutaneous disease has been shown to facilitate the transmission of HIV infection. Therefore early identification and treatment of HSV-2 is fast becoming a strategy for preventing HIV transmission. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of HSV-2 among attendees of an HIV counselling and testing Centre (HCT), at a large HIV treatment centre in Lagos, Nigeria. It was a cross sectional study among clients presenting for voluntary HCT, who were counselled and screened for HIV and HSV-2. SPSS for window Version 17 was used for data analysis to carry out socio-demographic distribution of participants, χ2 for association of variables with HSV-2 and the strength of the association determined by Pearson correlation. Two hundred and fifty eight participants enrolled for the study with 60% of participants being female. The most prominent age group was 24- 29 years (22.6%) for female and 30-35 years for male (25.2%). The prevalence of HIV and HSV-2 among the participants was 29.8% and 9.7% respectively. In addition, 7.8% tested positive to both HSV and HIV, with HSV-2 prevalence among the participants that tested positive to HIV significantly higher than participants that tested negative to HIV (P < 0.001). The strength of the association by partial correlation demonstrated a medium correlation for HIV and HSV-2 and a weak correlation for age group and HSV-2 (0.359 and 0.187 respectively). The association between HSV-2 and HIV infection is attested by this study showing a high prevalence of HSV infection among HIV positive participants.

Keywords: HSV-2, HIV, Serotesting

Cite this paper: Bamidele Oke , Sunday Omilabu , Nkiru Odunukwe , Oliver Ezechi , Olumuyiwa Salu , Rosemary Okoye , Olufunto Kalejaiye , Nkiruka David , Azeez Anjorin , Adesegun Adesesan , Babatunde James , Remilekun Orenolu , Adebukola Adetunji , Dave Oladele , Jane Okwuzu , Herpes Simplex Virus-2 Sero-testing among Individuals Presenting for HIV Counselling and Testing in a Centre in Nigeria, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20140301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) is a worldwide common human viral infectious agent and is one of the most prevalent sexually transmitted infections[1]. HSV is known to have two serological subtypes, which are HSV-1 and HSV-2. Typically, HSV-1 is acquired in childhood and causes orolabial ulcers, while HSV-2 is sexually transmitted and causes ulcers of the anal and genital regions. But this classical trend now varies, because both oral infections with HSV-2 and genital infection with HSV-1 are increasingly documented, probably as a result of oral-genital sexual practices[2].The disruption by HSV-2 of the genital epithelial barrier, causation of genital ulcer and frequent recurrence of infectious episodes of asymptomatic viral shedding, has been identified to have potential role in driving the scourge of HIV transmission[3]. HIV-1infected persons have been shown to have significantly higher rates of HSV-2 infection than non HIV-1 positive individuals[4,5].The large majority of persons with genital herpes do not know they have the disease; therefore infected individuals can inadvertently infect others[6]. Hence, the advocacy of HSV-2 diagnosis and suppression is fast becoming a strategy for preventing HIV transmission and slowing the rate of HIV disease progression[7].Western blot is the diagnostic gold-standard for HSV infection, but it is costly and only available in reference laboratories[8,9]. More available and accessible are type-specific serologic testing based on glycoprotein G, which is increasingly being used as part of the initial evaluation of persons presenting for HIV care, in order to diagnose asymptomatic or unrecognized HSV-2 infection [10,11].In Nigeria, HSV-2 screening is not routinely offered in STD clinics; even in those presenting with genital ulcer disease. This often leads to unrecognised HSV-2 infection and inappropriate treatment. Also data on HSV-2 and HIV is lacking in this country. Hence in this study, we offered HSV-2 screening to clients that presented for HIV counselling and testing (HCT) at the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR), with a sequel evaluation of the association of HSV-2 and HIV infection among the participants.

2. Objective

- To determine the seroprevalence of HSV-2 among attendees of a HIV counselling and testing Centre (HCT), at a large HIV treatment centre in Lagos, Nigeria.

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Study Type and Population

- A cross-sectional study carried out between September 2011 and July 2012 in the cosmopolitan city of Lagos, at the HIV counselling and testing centre (HCT) of a large HIV treatment centre (NIMR) in south-western Nigeria. Nigerian Institute of Medical Research currently provides comprehensive HIV care for more than 19,000 positive persons and has an average of about 50 persons daily presenting for HCT.A sampling frame for eligible participants was generated from a daily list of persons presenting for HCT each morning for the period of the study. Systematic sampling was then done from the daily sampling frame to select willing participants for the study for each day. They were counselled as per protocol for HIV testing and also counselled on HSV-2 and genital infections. Those eligible gave written consent and completed a structured questionnaire which included demographic details, sexual orientation and history of previous or present genital ulcer.

3.2. Laboratory Method

- They then had venepuncture for 4mls of whole blood which was collected into an Ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic acid sample bottle. A drop was used for HIV rapid test using Uni-Gold HIV rapid test (Trinity Biotech, Ireland) and Determine HIV-1/2 rapid test (Abbott Laboratories®, Tokyo, Japan).Plasma was separated by standard techniques of preparation of samples for clinical laboratory analysis into plain vials and was stored at -20 t0 -85℃. The serological test was performed using Enzyme Immuno Assay (ELISA) for IgM antibodies to Herpes Simplex Virus type 2 in human plasma and sera with the "capture" system kit from Dia.Pro. Diagnostic Bioprobes, (Milano – Italy). The manufacturers reported a specificity and sensitivity greater than 98% when compared with a US FDA approved ELISA kit and western blot[12]. The assay is based on the principle of "IgM capture" where IgM class antibodies in the sample are first captured by the solid phase coated with anti IgM antibody. The assay was carried out as instructed by the manufacturer, taking care to maintain the same incubation time for all the samples in testing as recommended. The test results were interpreted as a ratio of the sample OD450nm greater than the Cut-Off value (Negative control + 0.250).

3.3. Data Management

- Data analysis was done using SPSS for window Version 17, to examine the relationship between demographics and sero-positivity for HSV-2 and HIV[13]. Analysis included socio-demographic distribution of participants, χ2 for association of variables with HSV-2 and the strength of the association determined by Pearson correlation.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

- Ethical approval was obtained from NIMR Institutional Review Board and informed and written signed consent were obtained from participants. Both sexes of ages above 18 who were presented for HCT were eligible for the study. However, acutely ill patients who needed immediate attention and likely hospital referral were excluded. Those not willing to have venepuncture for blood collection were also excluded, as finger prick was the standard method for HIV HCT by the rapid test kits. This is because 4 mls of whole blood was required for both HSV-2 and HIV screening, as compared to a finger prick for HIV rapid testing only.

4. Results

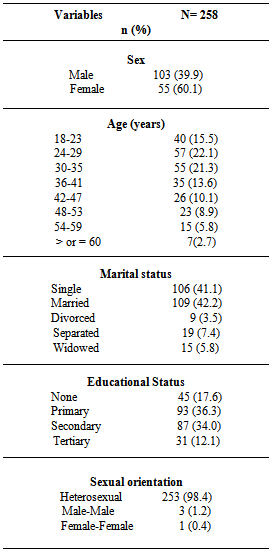

- A total of 258 participants enrolled in the study, 155 (60.1%) were female, while 103 (39.9%) were male. The mean age of the studied population was 34.8 (SD ± 11.2) years and the modal age was 24 years. The predominant age group for female was the 24-29 years (22.6%), while that of male was 30-35 years (25.2%). The 24-29 years age group had the highest population of single participants (18.4% for male and 14.2%for female respectively), while the 30-35 years age group had the highest married participants (female= 12.3%, male= 9.7%).Table 1 further summarises the sociodemographic characteristics of the group; more participants were married 109 (42.2%) and a greater number of them had primary education 93 (36.3%). Out of the study group, heterosexual sexual orientation was 253 (98.4), while only 3 (1.2%) and 1 (0.4%) reported male-male and female-female respectively.

|

|

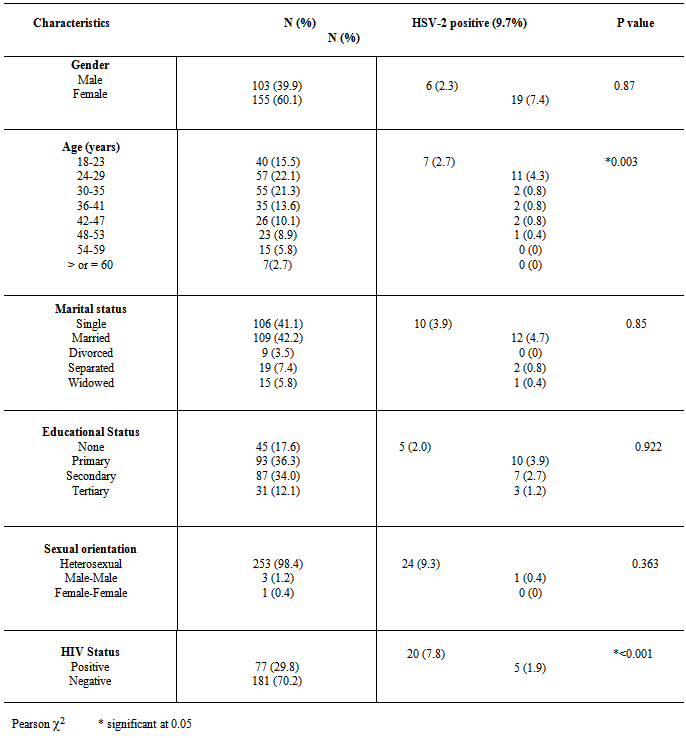

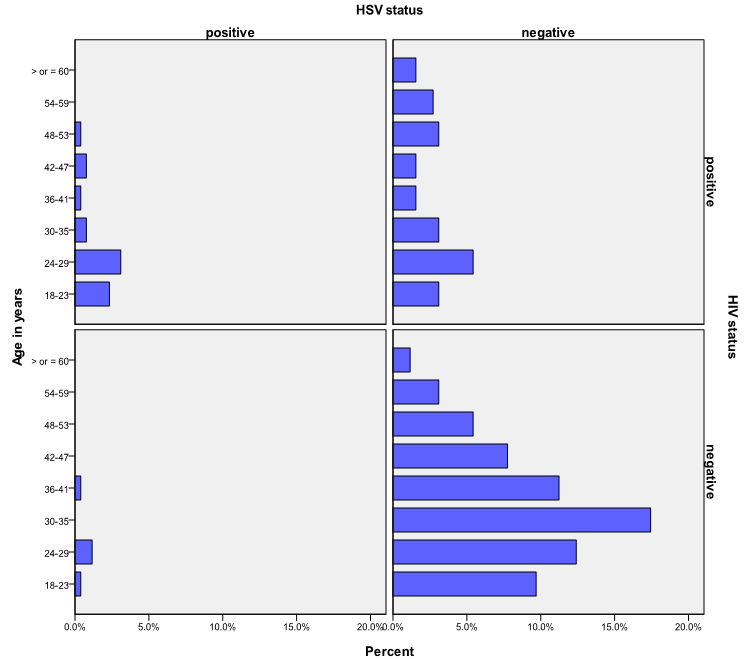

- The age group and gender distribution with HIV and HSV-2 status is shown in Figure 1 and 2 respectively. The 24-29 age group showed higher sero-positivity to HIV and HSV-2 (8.5%) and (4.3%) respectively, than other age groups. While 29 (11.2%) males were positive for HIV, 48 (18.6%) females were positive for same. At the same time 6 (2.3%) males were positive for HSV-2 as 19 (7.4%) females tested positive for the infection.

| Figure 1. Age distribution with HSV-2 and HIV status |

| Figure 2. Gender distribution with HSV-2 and HIV status |

|

5. Discussion

- The synergistic association between HSV-2 and transmission of HIV can be considerable in populations that have high prevalence’s of both viral infections[3, 6] This has been demonstrated in this study with the prevalence of HSV-2 among the participants that tested positive to HIV, significantly higher than participant that tested negative to HIV (P< 0.001). The two viruses' shared route of sexual transmission has severally been attributed for this finding [14,15]. The global elevated prevalence of HIV among women has been observed in other population-based studies [16, 17]. This is ascribed to the larger mucosal surface area of the female genital tract and the receptive role of women in sexual intercourse, resulting in higher male-to-female transmission risk per exposure[6,18]. This study also reflects this with women more at risk of HIV and HSV-2.Since the late 1970s a rise in HSV-2 seroprevalence has been observed in the general population in the USA, reaching 22% for the period 1988 to 1994 and was 17.0% in 2004[19]. Similar HSV prevalence’s have been reported in Europe and in Africa. However a wide range of prevalences (10-70%) has been reported in Africa, probably due to differences in socio-demographic distribution[6]. On the contrary, the prevalence of HSV-2 among the participants in this study (9.7%) is rather lower than that earlier documented in Nigeria by Dada et al (1998) and Agabi et al (2010). They reported a prevalence of 57 and 87% among commercial sex workers and patients attending a Sexually Transmitted Infections Clinic respectively using IgG serotesting[20,21]. The higher risk group of their participants who were commercial sex worker or STD clinic attendees, may have contributed to the recorded high prevalence, More importantly, the use of IgG sero-testing which does not represent current or primary infections as compared to use of IgM which detects more recent infection, for sero-testing in this study can be ascribed for this variation.Both HIV and HSV-2 infection has been shown to be more prevalent among participants younger than 30 years old in this study. As shown in Figure 1, the 24-29 years age group had the highest population of participants that tested positive to both HSV-2 and HIV. Evidence from meta-analysis and clinical studies indicates that herpes simplex virus type 2 is almost always transmitted as a result of sexual contact and more prevalent among sexually active persons[16, 22]. In addition, the use of condom as a preventive means for STDs and HIV as been established[23] .Only 22% of this group reported the use of condom, with 76 % of them being positive for HIV. Therefore the concern is being expressed of this finding in consistency with other investigators on the association between HSV-2, HIV sexual transmission and limited condom use for prevention[22, 24, 25].Recognition of the burden of HSV-2 is required in order to aptly tackle the control and prevention of HIV and indeed make HSV-2 screening routine in HIV and STDs clinics, where this is not been done at the moment. This study is limited by not performing IgG ELISA along with IgM testing to distinguish new and old HSV-2 infection.

6. Conclusions

- The link between HSV-2 and HIV infection is also attested by this study showing a high prevalence of HSV infection among HIV positive participants. This association between HSV-2 and HIV infection has major public health implications for Nigeria.The prevalence of these infections among young people highlights the greater need for enhanced counselling and education among this group, to increase awareness and precautions against unprotected sex.Direct linkages between HSV-2 and other STI during HIV counselling and testing would be useful in enhancing the control of HIV in Nigeria.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Ojerinola O. Oriaku C. and other members of staff of HCT.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML