-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2013; 2(2): 13-18

doi:10.5923/j.ijpt.20130202.01

Efficacy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM): Treatment of Asthma in Children in Urban (Polluted) Areas

1Coordinator of Sustainable Business program and researcher of environmental education. Barentszstraat 144-1013 NS Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2The Hague University of Applied Science, Department International Business Management Studies (IMBS) Barentszstraat 144-1013 NS Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Correspondence to: Kopnina Helen, Coordinator of Sustainable Business program and researcher of environmental education. Barentszstraat 144-1013 NS Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Although many publications have documented the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in children and adolescents, the recent review showed that there are only few well-controlled studies that support the efficacy of CAM in the treatment and clinical improvement of children with asthma. However, some evidence has been found that specific CAM techniques are differentially associated with psychosocial outcomes, indicating the importance of examining CAM modalities individually, as well as within culturally specific contexts. Based on the previous study of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) treatment in children’s asthma, this study examined the efficacy of TCM in areas with differing air pollution. This study is based on a longitudinal qualitative data and observations of families of children with asthma collected between 2009 and 2012 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The study results indicate that while TCM treatment of children can be beneficial to treatment of asthma, environmental pollution renders positive effects of alternative treatment largely ineffective.

Keywords: Asthma, Children, Chinese Traditional Medicine (CTM), Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM), Environmental Health, Pollution, Urban Areas

Cite this paper: Kopnina Helen, Efficacy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM): Treatment of Asthma in Children in Urban (Polluted) Areas, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 2 No. 2, 2013, pp. 13-18. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpt.20130202.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in Patients with Asthma

- In the Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Indian, and Western cultures, herbal and combination therapies appear to be commonly used for asthma. As opposed to the mainstream Western medicine, traditional medicine often use holistic approach to treating asthma, perceiving it in broader terms of general well-being rather than in strict diagnostic terms of respiratory condition, sometimes even disputing its chronic manifestations and viewing asthma as a potentially curable illness. Well-controlled scientific studies have not been performed on many of the Asian herbal therapies or various herbal components (active ingredients), and more needs to be done to assess the composite effects of many herbal remedies[1]. In Western evaluations of alternative medicine, the main question has been whether a given therapy has more than a placebo effect[2]. Although many publications have documented the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in children and adolescents, the recent review[3] showed that most have lacked the scientific rigor to establish clear benefits over so-called conventional medicine, and the role of placebo effect in these studies is largely disputed[4]. CAM is commonly defined as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine. There are only few well-controlled studies that support the efficacy of CAM in the treatment and clinical improvement of children with asthma[5]. Arnold et al[6] addressed efficacy and safety of herb and plant based preparations for treatment of asthma. Primary outcomes led authors to conclude that evidence base for the effects of herbal treatments is hampered by the variety of treatments assessed, poor reporting quality of the studies and lack of available data. Positive findings in this review warrant additional well-designed trials in this area. However, some evidence has been found that specific CAM techniques are differentially associated with psychosocial outcomes, indicating the importance of examining CAM modalities individually, as well as within culturally specific contexts[7, 8].Despite conflicting evidence, CAM therapies such as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Ayurveda medicine, herbal therapy, acupuncture, yoga, homeopathy, chiropractic medicine, and massage therapy, continue to gain popularity as modalities for the treatment of asthma in Western Europe in general and in The Netherlands in particular[1, 8]. CAM use in Europe is widespread because parents are seeking a cure for asthma, as well as alternative methods that are natural, without long term side effects[6, 9, 10]. In The Netherlands, CAM is still not officially recognized as a viable alternative by most medical practitioners, pharmaceutical and insurance companies[11]. It is perhaps not surprising that asthma patients’ non-compliance to the prescribed medical regime is seen by most practitioners as a matter of ‘denial’ – either of rationality guiding the evidence-based medicine, or of the patients’ own identity as asthma sufferers. The medical practitioners, themselves educated within the dominant paradigm, continue to offer the patients pharmaceutical based medicine as the most effective and scientifically-validated form of medicine[12]. These medicines typically contain long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) in combination with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), the long-term use of which indicates serious side effects[13, 14]. State-supported pharmaceutical industry and insurance companies largely subsidize delivery of these medicines; while CAM delivery is largely funded privately[11].

1.2. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Asthma

- Li and Brown[15] analyzed literature regarding the care of asthmatic children using biologically based CAM therapies and identified three clinical studies involving children and anti-asthma TCM herbal remedies. The three specific TCM formulas were the following: Modified Mai Men Dong Tang (mMMDT) consisted of five herbs; Ding Chuan Tang (DCT) comprised of nine herbs; STA-1 consisted of a combination ofmMMDT (10 herbs) and Lui-Wei0Di-Huang (LWDHW, 6 herbs). In all three studies, the subjects continued their prescribed medical regimen and were either given a TCM formula or a placebo. The treatment subjects, demonstrated improved forced expiratory volume (FEV1) outcome, compared to the subjects given a placebo in all three studies. All participants were able to tolerate the TCM formulas safely.Another study utilizing the principles of TCM applied Sanfujiu (a paste that consist of five Chinese medicines) to treat allergies and asthma by increasing yang qi (nature of the sun; hot) in the lungs. This study enlisted 119 subjects of all ages. Those with asthma were more likely to report that the Sanfujiu treatment was effective compared to subjects with other allergic diseases[16]. Stockert et al.[17] study examined the effectiveness of a combination of laser acupuncture and probiotics as a form of treatment for asthma was reviewed. A small group of 17 children was enlisted to participate in a randomized, placebo- controlled, double-blind study that treated asthmatic children with TCM methods. Laser acupuncture was substituted for needle acupuncture and probiotics of nonpathogenic Enterococcus faecalis was administered in place of the TCM herb, Jin zhi. The control group was treated with a laser pen and given placebo drops to ingest. The results of the study demonstrated that the treatment group had significantly decreased weekly peak flow variability as a measure of bronchial hyper-reactivity. It is remarkable that no consistent clinical trials aside from rather patchy ad hoc studies have been conducted up till present. An important part of the assessment of CAM modalities is the therapeutic-toxicological safety profile (risk- benefit ratio), and further research evaluating the clinical efficacy and mechanism of action of various CAM interventions for asthma is greatly needed[18]. Li and Brown[15] and Mainardi et al.[19] summarized the difficulties of testing biologically based TCM modalities as the following: 1. Isolation and identification of active constituents may be difficult because of nature of the herbs and its manufacture and preparation processes; 2. Synergistic effect of herbal combinations complicates the ability to determine the exact effect; 3. TCM formulas are traditionally created for the individual; standardization of TCM may not be effective; Random, blinded studies are difficult to conduct when the subject’s perception of CAM therapies may influence the results; 4. There is a need for more controlled clinical trials to test the efficacy of TCM formulas.Additional hypothesis for the lack of conclusive evidence on efficiency and safety of TCM may be due to the fact that the type of funding may have determinant effects on the design of studies and on the interpretation of findings[12]. Funding by the industry is associated with design features less likely to lead to finding statistically significant adverse effects and with a more favorable clinical interpretation of such findings. Disclosure of conflicts of interest should be strengthened for a more balanced opinion on the safety of drugs[20]. At present, there are few consistent Western-based studies that address clinical trials of TCM (while there are quite a few published in other languages, such as Mandarin). Social scientists and mainstream Western practitioners alike continue to disregard CAM as a serious alternative to potentially harmful conventional medicine[21]. Astma Fonds, official Asthma patients’ organization in The Netherlands refuses to place any materials related to TCM on its site[11].

2. Asthma and Air Pollution

- Recent studies show a relationship between exposure to air pollutants for both the occurrence of the disease and exacerbation of childhood asthma[22]. There is growing evidence of asthma symptoms in children who live near roadways with high traffic counts[23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. These recent international studies provide strong evidence for traffic pollution as a risk factor for both asthma exacerbation and onset[29]. The recent population-based matched case-control study of Li et al[30] examined the relationship between air pollution and severity of asthma symptoms. Asthma events were associated with traffic pollution and proximity to primary roads, providing moderately strong evidence of elevated risk of asthma close to major roads. Particularly traffic pollutants were linked to higher occurrences of asthma (31, 32, 33). Another study of urban air pollution and emergency room admissions for respiratory symptoms in Italy demonstrates that exposure to ambient levels of air pollution is an important determinant of emergency room (ER) visits for acute respiratory symptoms, particularly during the warm season. ER admittance may be considered a good proxy to evaluate the adverse effects of air pollution on respiratory health[34].

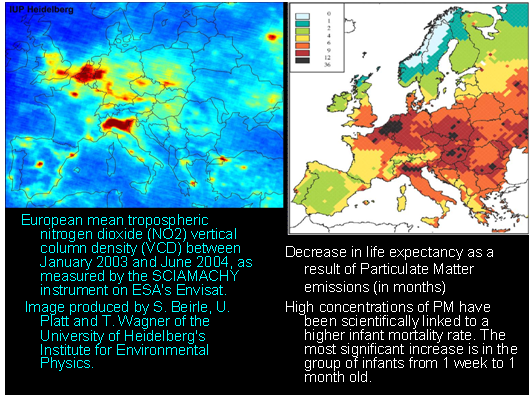

2.1. Air Pollution in the Netherlands

- The Netherlands relies for 92% on fossil sources of primary energy. Emissions and waste include Carbonmonoxide (CO); Particulate Matter (PM10, PM2,5); Nitrates (NOx); Sulfates (SOx); Heavy metals (As, Cd, Cr-VI, Ni, Hg, Pb); Volatile Organic Components (VOCs); Polycyclic Aromatic Carbohydrates (PACs). Figure below shows pollution density in Europe. It appears that the Netherlands is one of the most polluted countries in Western Europe, according to the Dutch environmental group Stichting Natuur en Mileu. The organisation bases its claim on a survey commissioned by the European Commission[35]. A number of recent studies published in leading medical journal Lancet showed that poor air quality in the Netherlands correlates with incidences of respiratory illness and death[36, 37].With more than seven million passenger vehicles on its roads, the Netherlands is the sixth largest automotive market in Europe[38]. According to Eurostat[39], car density in The Netherlands is 460 per 1000 inhabitants, up from 371 per 1000 in 1991. This is remarkable, because the Netherlands is a small country with a highly developed public transportation system. According to the national research on Mobility in The Netherlands, Mobiliteitsonderzoek Nederland (MON) published in 2010, there are 7,348 million households. Four out of five (79,1%) owns one or more cars, 20,9% does not own a car. There are very few car-less families (4%), and four in five single parent families own a car. According to the recently published dissertation of Hans Jeekel, titled ‘The Car-Dependent society’[40] 20% of the car-less persons can simply not afford a car. Together with other air pollutants, traffic pollution contributes significantly to the high occurrence of asthma in The Netherlands[36].

3. Asthma in the Netherlands

| Figure 1. Air pollution in Europe |

4. Case Study

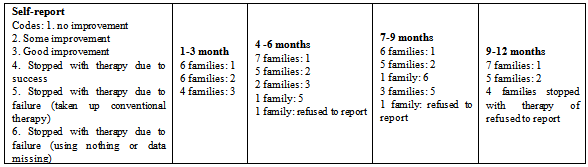

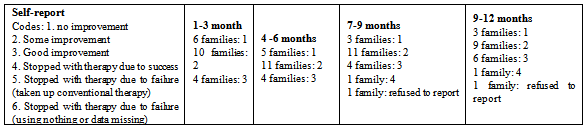

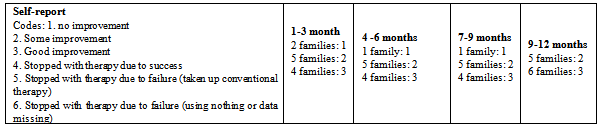

- However, the efficacy of CAM and TCM is largely disputed, especially in the case of asthma caused by severe air pollution factors. The case study conducted involved a sample of 47 Dutch children between 7 and 13 year old who were diagnosed with asthma. The study involving interviews with children and their families was conducted between May 2009 and January 2012. There were two groups of children whose parents refused to use conventional medicine and resorted to TCM (often in combination with other types of CAM therapy such as acupuncture) and one group that used conventional medicine.

|

|

|

5. Reflection

- The sample is too small to make any definite conclusions; however, if any generalization is to be made, it appears that the children from the more air polluted area showed fewer positive effects of TCM. A salient detail is that among twenty well-to-do families of the second group, almost all owned at least one family car (18 families) as opposed to only 6 car-owners from the first group. During the research on perception of environmental and health effects of car ownership, it appeared however that lower income families expressed a great interest in owning a car as soon as they were financially able to[42]. While the parents of the second group expressed greater awareness of facts about asthma and asthma medication, practically no family members from either the first or the second and third group expressed awareness of adverse effects of traffic pollution on asthma.

6. Conclusions

- It may be too premature to draw conclusions based on this small sample pilot study, yet recommendation can be made that TCM may not be as effective in treating childhood asthma if it is caused by or exacerbated by residence in air polluted areas. Conventional medicine seemed to have consistent effect on symptom reduction in children with polluted areas. However, concerns about safety of long-term use of conventional medicines remain. The study also raises questions about efficacy of asthma treatment if measures addressing air pollution in general and traffic in particular are not taken.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML