-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2026; 16(1): 9-20

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20261601.02

Received: Dec. 26, 2025; Accepted: Jan. 22, 2026; Published: Feb. 7, 2026

Psychometric Properties Evaluation of the TalentDNA Inventory

Ary Ginanjar Agustian1, Madyasta Aji Bhirawa2, Muhammad Aliyandri2, Dwitya Agustina3, Wan Nurul Izza Wan Husin4

1Advisory Board, Universitas Ary Ginanjar, Jakarta, Indonesia

2Department of Psychology, Universitas Ary Ginanjar, Jakarta, Indonesia

3Department of Management, Universitas Ary Ginanjar, Jakarta, Indonesia

4Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Development, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Perak, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Wan Nurul Izza Wan Husin, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Development, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Perak, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The emergence of ‘talentism’ aligns with positive psychology’s central concern that is what enables individuals and communities to thrive. This study aimed to examine psychometrics properties of the TalentDNA Inventory, particularly its content validity, factorial validity and reliability. This scale consists of three major domains; Drive, Network and Action. A survey was conducted and 1217 responses (n=1217) obtained from Indonesian adults. The obtained findings indicate that this scale exhibits sound psychometrics properties particularly on its content validity, factorial validity and reliability. Results on item level Content Validity Index indicates that the items content are acceptable (I-CVI>0.78) based on the rating given by 10 subject matter experts. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) result also indicated that this scale possesses a stable three-factor structure with two underlying sub-factors for each factor. In terms of reliability, findings indicated that reliability for each domain, sub-domain and the overall scale are acceptable and good with Cronbach’s alpha values above .80. Therefore, this TalentDNA Inventory is valid, reliable and suitable to be used by adult group.

Keywords: Talent Assessment, Talentism, Construct Validity, Psychometrics, Positive Psychology

Cite this paper: Ary Ginanjar Agustian, Madyasta Aji Bhirawa, Muhammad Aliyandri, Dwitya Agustina, Wan Nurul Izza Wan Husin, Psychometric Properties Evaluation of the TalentDNA Inventory, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 16 No. 1, 2026, pp. 9-20. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20261601.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2025, talent management is projected to become a significantly more critical skill in the workplace by 2030 [1]. This projection reflects a broader transformation in how organizations conceptualize their workforce—not merely as a source of labor, but as a strategic asset whose development, engagement, and retention are central to long-term competitiveness. Within this evolving landscape, the concept of talentism emerges as an economic paradigm in which human talent constitutes the primary source of value creation. This paradigm can be productively interpreted through the theoretical lens of positive psychology, a field grounded in the scientific study of human strengths, well-being, and optimal functioning. Positive psychology offers a compelling framework for understanding why talent, rather than financial capital or industrial assets, has become the most significant economic resource in the modern era.From a positive psychology perspective, talentism is fundamentally aligned with the assumption that individuals possess unique strengths that, when effectively cultivated, contribute not only to personal fulfillment but also to collective flourishing. Human talent is increasingly conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing innate capacities, developed strengths, and the potential for exceptional performance across specific domains. Scholars generally conceptualize talent as an interplay between genetic predispositions, environmental influences, and intentional practice, rendering it both inherent and malleable. Contemporary research further emphasizes that this malleability is increasingly shaped by talent ecosystems rather than isolated individual effort [2], while the potential for exceptional performance is progressively linked to individual capability within organizational contexts [3]. Consequently, the interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental influence is no longer viewed as a static developmental process but as a dynamic requirement for organizational resilience, positioning talent as a sustainable resource that must be continuously recalibrated to meet the demands of a rapidly evolving global market.Extending beyond traditional cognitive metrics, talent is often conceptualized as a dynamic and multidimensional construct that incorporates creative problem-solving and socio-emotional competencies [4]. From a psychological standpoint, the transition from innate potential to domain-specific excellence is contingent upon an interactionist approach, wherein sustained engagement is facilitated by supportive ecological contexts and the availability of systemic capital [5]. This developmental trajectory is further optimized when individuals are able to leverage their signature strengths, as research in positive psychology suggests that the behavioral expression of these strengths serves as a primary catalyst for achieving psychological well-being and academic or professional excellence [6]. Accordingly, talent is no longer understood as a fixed trait but as an emergent property of the person–environment fit, requiring a synergistic alignment between individual aptitudes and systemic opportunities for refinement.Consistent with this view, current literature decisively moves away from static conceptions of ability, emphasizing instead that talent development is heavily reliant on ecological support systems. Developmental models highlight that talent evolves through deliberate practice, meaningful feedback, mentoring, and environmental enrichment. Access to resources, quality instruction, and psychologically supportive environments play a critical role in transforming latent potential into demonstrated competence. Empirical evidence further suggests that an individual’s capacity to develop is strongly bounded by access to educational and social capital, such that, in the absence of psychologically safe and resource-rich environments, innate potential is likely to remain dormant [7]. Therefore, talent is best understood as a dynamic and context-dependent phenomenon shaped by the continuous interaction between individual characteristics and ecological conditions.Importantly, the nature of human talent extends beyond measurable technical abilities. Increasingly, research asserts that talent is predicated less on fixed technical intelligence and more on a robust architecture of non-cognitive attributes, including resilience, curiosity, and intrinsic motivation [8]. These attributes not only enable individuals to perform effectively but also sustain engagement, adaptability, and long-term success in both academic and professional domains. Understanding talent through this broader lens has significant implications for education, leadership, and public policy, challenging institutions to move beyond narrow definitions of ability and adopt strengths-based approaches that recognize and cultivate diverse forms of human potential. By prioritizing the development of diverse human capabilities and character strengths, societies enhance individual flourishing while simultaneously building the psychological capital necessary for collective innovation and societal advancement in an increasingly complex global economy [9].Within this strengths-based paradigm, psychologists [10] introduced the VIA (Values in Action) framework to conceptualize character strengths. The VIA framework defines human character as the moral dimension of individual functioning, distinguishing it from temperament or cognitive ability. It is grounded in several key assumptions: character strengths are morally valued and socially beneficial, exhibit relative stability over time while remaining open to development, and are distinct from talents and abilities in that they reflect how individuals act rather than how well they perform. These assumptions position character strengths as foundational psychological resources that underpin ethical behavior, resilience, and well-being. By focusing on what is best in people rather than their deficits, the VIA framework provides a shared language for understanding and cultivating human goodness, reinforcing the conceptual alignment between talentism and positive psychology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Respondents consisted of 1217 adults (n=1217) from Indonesia, whose age ranging from 45 to 60 years old, with M=49.9 and SD=3.7. With regards to educational background, majority were bachelor degree holders (36.5%), followed by masters’ degree holder (21.2%), senior high schools (12.3%) and others (30%).

2.2. Measure

- TalentDNA Inventory is an inventory developed to reveal an individual’s talents particularly the natural talents and behavioural tendencies. While other conventional inventories mostly focus on acquired traits, competencies, or learned skills, TalentDNA emphasizes the identification of innate strengths that constitute the core “DNA” of human behaviour, which consistently shapes how individuals think, feel, and act across contexts. This instrument organizes human talents into three primary domains (D-N-A): Drive, Network and Action. Drive domain reflects individuals’ intrinsic motivations and inner forces that propel individuals toward goals and aspirations. It consists of two sub-domains; achieving and understanding. Achieving-drive consists of seven facets which are competitive, directive, goal-getting, optimiser, perfectionist, confidence and significance. Understanding-drive consists of eight facets which are aversive, collector, contemplative, equitable, explorer, noble, vigorious and visionary. Each of them consists of four items. The Network domain describes individuals’ interpersonal capacities that influence how people build, maintain, and nurture social relationships. It consists of two sub-domains: influencing and relating. Influencing encompasses seven facets, namely advisor, articulative, collaborator, courageous, convincing, developer, and energiser, which reflect tendencies related to interpersonal influence, communication, and social leadership within group contexts. Meanwhile, relating consists of eight facets, namely affectionate, caring, forgiving, generous, genuine, harmony, personaliser, and sociable, which capture relational orientations associated with emotional connection, empathy, and the maintenance of positive and harmonious social interactions.Action domain defines individuals’ cognitive and problem-solving orientation tendencies that guide how individuals process information and transform it into decisions or strategies. This domain encompasses two sub-domains; thinking and doing. Thinking-action consists of seven facets; contextual, focused, intuitive, innovative, logical, strategiser and troubleshooter. Doing-action consists of eight facets which are accountable, authoritative, decisive, fixer, flexible, initiator, resourceful and structured. Each of these facets consist of four items.Across these three domains, the scale measures 45 talent themes, offering a comprehensive portrait of an individual’s unique profile. Test results typically highlight the top 10 most dominant talents, which serve as the person’s signature strengths, as well as the bottom 5 talents, which represent areas that may require management rather than improvement.

2.3. Procedure

- A convenience sampling technique was employed in this study. Participants were recruited during a public event and were invited to voluntarily participate in the TalentDNA Inventory assessment. Prior to participation, an explanation of the purpose, procedures, and potential benefits of the assessment was provided. Interested participants submitted their email addresses, after which a secure link to the online TalentDNA Inventory was distributed via email. Participants completed the assessment independently at their convenience, with an average completion time ranging from 25 to 35 minutes. Upon completion, respondents received automated individualized feedback in the form of a personalized report summarizing their dominant talent profiles, along with interpretative information intended to facilitate self-reflection and understanding of behavioural tendencies.

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity

- Hypothesis 1 aimed to examine content validity of the TalentDNA inventory. Ten (n=10) subject matter experts (SME) were appointed based on their agreement. All of them were psychologists and work either as a practitioner or academicians. In the content validation form, the definition of domain and the items represent the domain are clearly provided. The SMEs were requested to critically review the domain and its items before providing score on each item. They were required to indicate the degree of relevance for each item. The degree was ranged from (1) the item is not relevant to the measured domain; (2) the item is somewhat relevant to the measured domain; (3) the item is quite relevant to the measured domain and (4) the item is highly relevant to the measured domain. Results on item level Content Validity Index (CVI) indicates that the items content are acceptable (I-CVI>0.78) based on the rating given by the experts. With all CVI values above 0.78, this finding indicates that the items content are valid [11] [12].

3.2. Factorial Validity

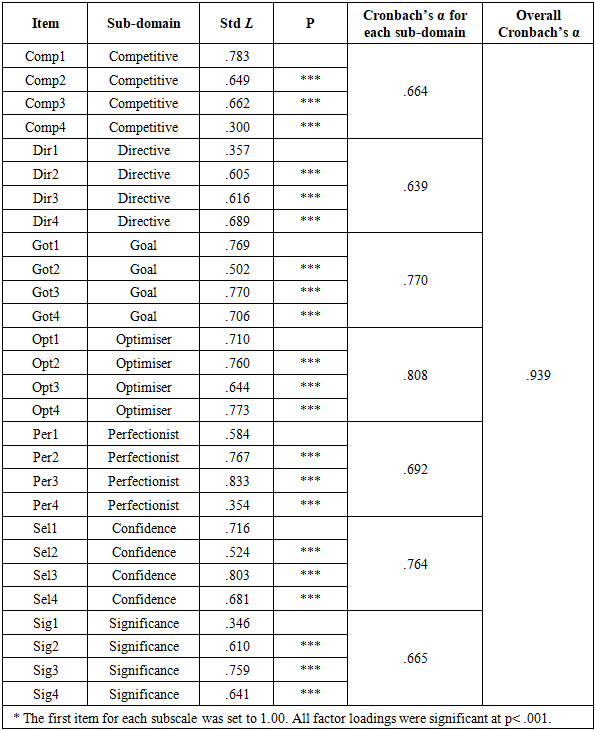

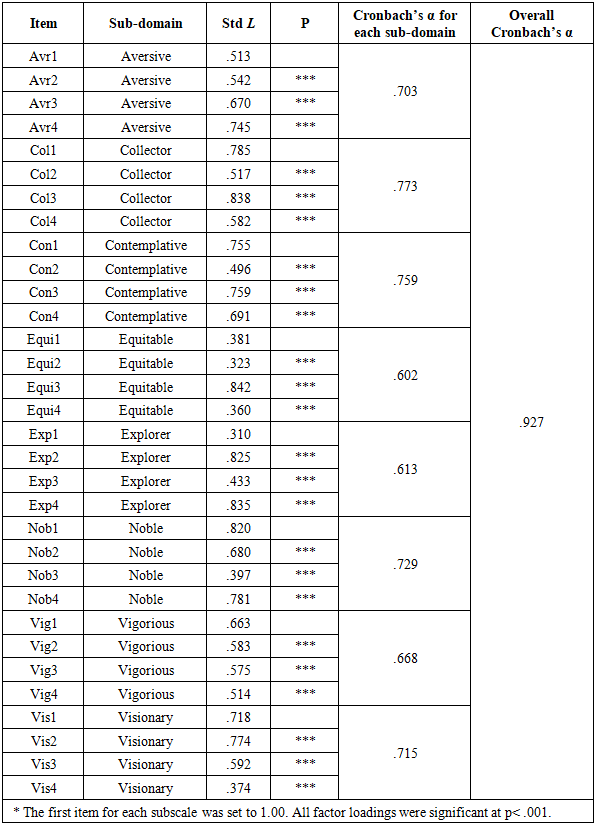

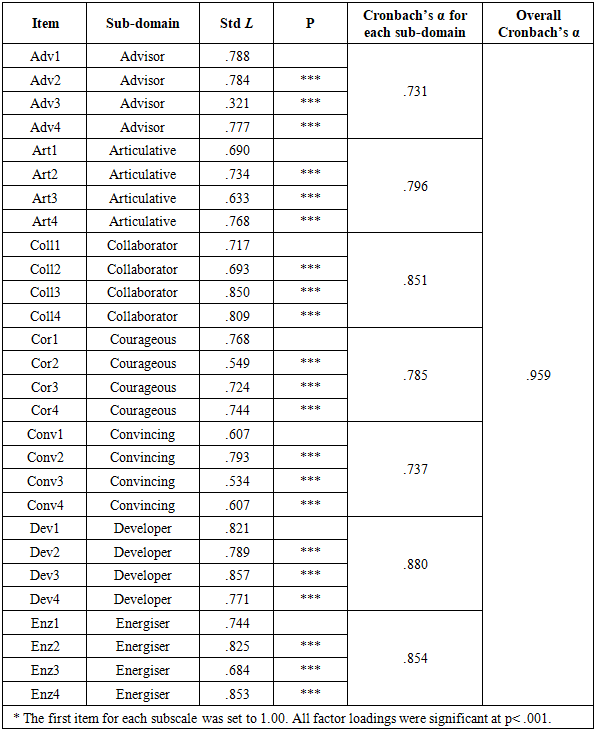

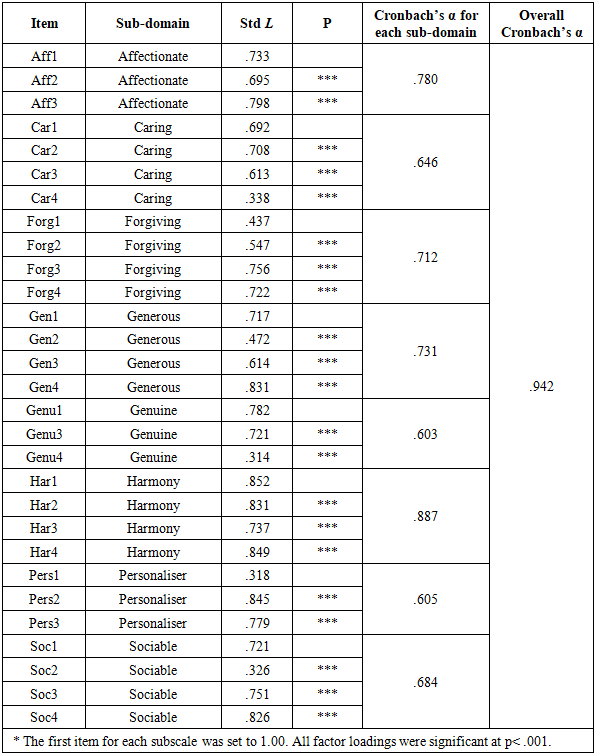

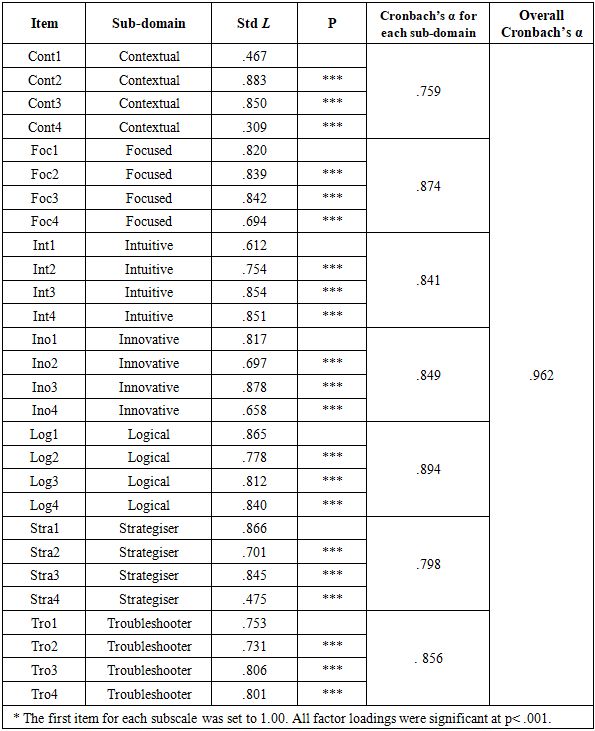

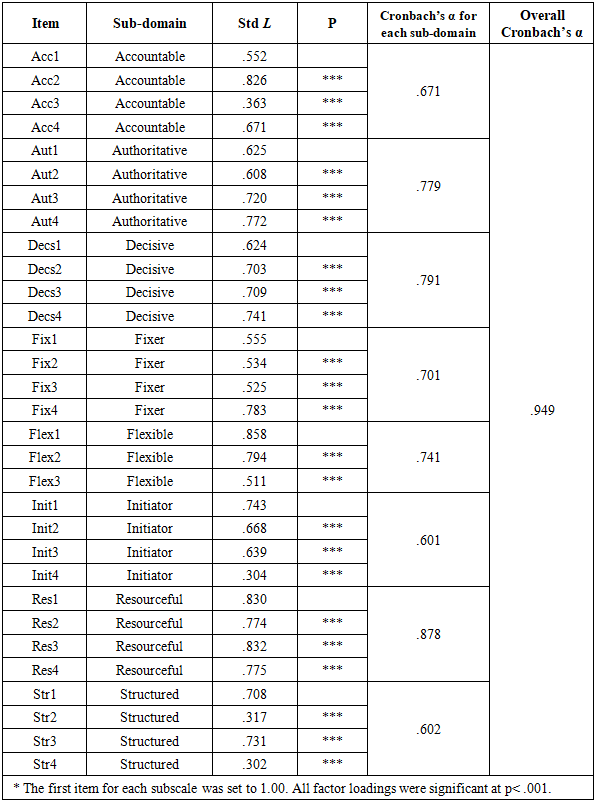

- Hypothesis 2 aimed to gather evidence on the internal factor structure of the TalentDNA Inventory construct. As outlined in the introduction, confirming factorial validity is essential in testing construct validity because it verifies the conceptual framework of a construct. Specifically, factorial validity examines how well the internal factor structure represents the TalentDNA Inventory construct by assessing whether the measured items load onto their respective domains [13] [14].The measurement model of TalentDNA Inventory construct was evaluated using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with AMOS software through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA is a statistical tool in SEM used to confirm factor structures that underlie a particular construct [15] [16] [17]. Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) was employed to assess the adequacy of the model as the parcels are generally treated as continuous data [16]. A. Factorial validity of the ‘achieving’ sub-domainCFA result on the hypothesized model for achieving sub-domainThe achieving drive sub-domain comprises seven facets namely competitive, directive, goal getting, optimiser, perfectionist, confidence, and significance with each subdomain measured by four items. The CFA results showed adequate support for the hypothesized model, χ² (329) = 2042, p = .000, χ²/df = 6.209, CFI = .903 and RMSEA = .065. The goodness-of-fit indices of the hypothesized model indicate an acceptable model fit based on certain index; the CFI was higher than .9 [13] [18] and the RMSEA was below than .08 [17]. Furthermore, an examination of the Standardized Regression Weights or loading estimates showed that all of the items had a Critical Ratio bigger than 1.96 (CR < +1.96) (ranging from 8.9 to 29.5) indicating that they were significant indicators of the achieving-drive sub-domain [15]. The loading estimates for majority of the items were also larger than .5 signifying that they were satisfactorily related to the measured domain [13]. Refer to Table 1 below for the fit statistics, loading estimates and reliability.

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.3. Reliability Analysis

- The reliability test was conducted for all domains and subdomains. The reliability coefficients for each domain are presented in Table 1 until Table 6. All alpha coefficients were satisfactory as most of the values for each subdomain are larger than .7 indicating that the items for the underlying subdomains are internally consistent [19] [20]. According to [13], for the newly-developed scale, Cronbach's alpha value of .6 is deemed acceptable. The internal consistency for the overall items for each domain was also high with Cronbach's alpha value of .9 indicating that all of the underlying items are internally consistent and assess the same domain.

4. Discussion

- The TalentDNA Inventory is a self-scoring measure that describes individual behavioural tendencies based on self-reported responses. The findings of this study confirm that the item content within the TalentDNA Inventory is both valid and was highly relevant to the constructs being measured. The acceptable item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVI) values indicate that each item adequately represents its intended domain, supporting the content validity of the scale. Similar levels of expert agreement have been reported in recent psychometric validation studies, where theoretically grounded items demonstrated strong content relevance and clarity [21]. Overall, the findings provide initial evidence that the TalentDNA Inventory possesses satisfactory content validity. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) results further revealed that each domain of the TalentDNA Inventory demonstrates a stable and valid factor structure, indicating that the items appropriately map onto their respective domains. Out of 176 items, all retained items showed significant factor loadings in measuring their intended constructs, supporting Hypothesis 2. This pattern of stable multidimensional factor structures is consistent with prior validation studies of behavioural and psychological inventories, which similarly reported strong factorial validity when scale development was guided by clear theoretical frameworks [22] [23]. It should be noted that four items were found to be non-significant during preliminary analyses and were subsequently excluded from the CFA. Such iterative item refinement is a common practice in scale development and aligns with established psychometric standards aimed at enhancing construct clarity and measurement precision [24].The reliability analysis indicated that the TalentDNA Inventory demonstrates good internal consistency across all domains, suggesting that the items within each domain consistently measure the same underlying construct. High reliability coefficients comparable to those observed in other multidimensional self-report instruments further support the robustness of the scale [21] [22]. Accordingly, Hypothesis 3 was supported. Collectively, these findings provide empirical support for the viability of the three-dimensional structure of the TalentDNA Inventory—drive, network, and action—along with its satisfactory content validity and reliability.Taken together, the present findings are supported by multiple strands of psychometric evidence. First, the acceptable item-level CVI values (I-CVI > .78) are consistent with established recommendations for content validity in scale development studies [11] [12]. Second, the CFA results across all six sub-domains demonstrated acceptable to good model fit indices (CFI ≥ .90; RMSEA ≤ .08), aligning with commonly accepted thresholds reported in psychometric validation literature [13] [16]. Third, the consistently high internal consistency coefficients (α > .80) across domains mirror reliability patterns observed in other validated multidimensional behavioural instruments [21] [22]. Collectively, this convergence of evidence strengthens confidence in the structural integrity and measurement precision of the TalentDNA Inventory.When compared with existing psychometric instruments, the TalentDNA Inventory demonstrates psychometric properties that are largely comparable to other recently validated multidimensional behavioural measures [21] [22]. The TalentDNA Inventory exhibits a stable factor structure and strong internal consistency across domains, despite differences in item length and construct focus. Notably, while the TalentDNA Inventory comprises a relatively larger number of items, the process of item removal and refinement observed in the present study mirrors best practices reported in prior scale development research, supporting its methodological rigor and alignment with contemporary psychometric standards [23] [24].Overall, the present findings indicate that the TalentDNA Inventory demonstrates acceptable psychometric properties, supporting its use as a structured measure of behavioural tendencies within adult populations. By facilitating greater understanding of one’s own and others’ characteristic styles, the instrument supports more adaptive behavioural responses, improved decision-making, and effective behavioural management in both personal and organizational contexts.

4.1. Implications and Recommendations for Future Research

- Psychometric assessments play an important role in organizational and professional settings by providing insights into individuals’ behavioural tendencies, thereby supporting adaptation to workplace challenges and enhancing team dynamics. Within this context, the TalentDNA Inventory offers a structured approach to identifying intrinsic behavioural patterns that influence how individuals think, feel, and act across different situations. Rather than serving as a labeling mechanism, the inventory emphasizes self-awareness and behavioural understanding, which are critical for personal development and effective organizational functioning.At the individual level, the TalentDNA Inventory may assist individuals in recognizing their strengths, motivational drivers, and potential blind spots, which can inform career development and interpersonal effectiveness. At the organizational level, the instrument may support recruitment, talent development, and succession planning by facilitating alignment between individual behavioural tendencies and job or role requirements. Such applications are consistent with the growing emphasis on evidence-based assessment practices in organizational psychology.Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that the reliance on self-reported data may introduce response bias, and the relatively large number of items may warrant further examination of item redundancy in future refinement studies, as recommended in contemporary psychometric research [24].Future research should extend the validation of the TalentDNA Inventory by examining additional sources of validity evidence, including convergent validity, discriminant validity, and predictive validity, through comparisons with established psychological measures and relevant behavioural outcomes. Cross-cultural validation and longitudinal studies are also recommended to further strengthen the generalizability and interpretability of the instrument.

5. Conclusions

- In the context of evolving workforce demands, the present study provides empirical evidence supporting the TalentDNA Inventory as a psychometrically sound instrument for assessing behavioural tendencies in adults. Evidence from content validity analysis demonstrated acceptable expert agreement across items, while confirmatory factor analyses supported a stable three-domain structure comprising drive, network, and action, each with coherent sub-domains. In addition, the consistently high internal consistency coefficients observed across domains indicate satisfactory measurement precision and reliability.From a measurement perspective, these findings align with established psychometric standards for scale development and validation, reinforcing the structural integrity and interpretability of the TalentDNA Inventory. The use of a theoretically grounded framework, combined with systematic item evaluation and refinement, strengthens confidence in the inventory’s capacity to capture meaningful individual differences in behavioural tendencies.Beyond its psychometric properties, the TalentDNA Inventory holds potential value for evidence-based talent assessment and development practices. When situated within broader research on talent management and positive psychology, the inventory may serve as a structured mechanism for supporting self-awareness, role alignment, and talent development initiatives in organizational settings. However, its application should be informed by continued validation efforts, including examinations of convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity across diverse populations and contexts.Overall, the present study contributes to the growing literature on talent assessment by providing a validated measurement tool that integrates theoretical coherence with empirical rigor. Future research that extends the validation of the TalentDNA Inventory across cultures, occupational groups, and longitudinal designs will further clarify its utility and generalizability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to acknowledge Universitas Ary Ginanjar for providing research grant for this research. Appreciation is also extended to the institutional leadership and colleagues for their administrative assistance and professional support throughout the research process. The authors further thank all participants and individuals involved in data collection for their valuable time and cooperation. The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML