-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2026; 16(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20261601.01

Received: Jan. 3, 2026; Accepted: Jan. 26, 2026; Published: Feb. 5, 2026

Beyond the Essay: Collaborative In-Class Assignments to Boost Engagement and Curb AI Reliance

Elizabeth Valenti

Grand Canyon University, United States

Correspondence to: Elizabeth Valenti, Grand Canyon University, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

As generative AI challenges academic integrity, this pilot study tested collaborative in-class assignments as an alternative to traditional papers. Using a posttest-only, non-equivalent control group design with 812 psychology students, outcomes compared grades, participation, DFW rates, and satisfaction. Results showed a 26% increase in participation, a 6.5% drop in DFW rates, and a 0.41 GPA gain. Satisfaction improved modestly, with qualitative feedback highlighting peer connection and preference for collaboration. Findings suggest this model enhances engagement, persistence, and performance while reducing reliance on take-home work vulnerable to AI misuse.

Keywords: Collaborative learning, Academic integrity, Artificial intelligence, Student engagement, Active learning, Psychology education

Cite this paper: Elizabeth Valenti, Beyond the Essay: Collaborative In-Class Assignments to Boost Engagement and Curb AI Reliance, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 16 No. 1, 2026, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20261601.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Higher education faces a critical juncture with the growing use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools such as ChatGPT. These technologies provide sophisticated support for written assignments but raise concerns about authenticity, critical thinking, and the integrity of learning [1]. Faculty are reexamining traditional take-home assignments and seeking alternatives that maintain learning outcomes while addressing these new challenges.While AI can enhance productivity, it may also encourage passive learning by bypassing essential cognitive and metacognitive processes [2]. Reliance on AI reduces opportunities for meaningful engagement with course material and increases risks of plagiarism, misattribution, and broader integrity violations [1]. Evidence [3] supports rethinking assessment design in light of AI, suggesting that reflective, collaborative in-class activities can foster authentic learning while limiting opportunities for misuse.Declining attendance and participation add to these concerns. Research indicates reduced classroom engagement, particularly in lecture-based courses, following the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Easy access to AI-generated content allows students to skip class yet still submit competent assignments, undermining active learning, peer collaboration, and the value of the classroom experience [5].In response, institutions are reemphasizing active engagement, a multidimensional construct involving behavioral, emotional, and cognitive investment in learning [6]. Authentic classroom experiences serve as protective factors against disengagement and dishonesty [7,8]. Scholars caution that while AI can benefit students, unstructured use risks superficial learning. Effective pedagogy must both mitigate dishonesty and promote well-being and authentic engagement [9].

1.1. Theoretical Framework

- This study draws on foundational and contemporary theories of student learning and engagement. Kuh’s [10]. framework on high-impact practices highlights active, collaborative learning and sustained effort, which enhances retention, deepens learning, and fosters meaningful interactions. Tinto’s [11] theory of student departure emphasizes academic and social integration as key to persistence. Recent research supports these ideas. Additional research [12,13] show that well-designed collaborative environments improve motivation, resilience, and critical thinking. In psychology education, case-based collaboration has been linked to stronger application of theory and higher satisfaction [14]. Self-determination theory [15] underscores the importance of relatedness, autonomy, and competence; in-class collaboration meets these needs by fostering shared accountability. Vygotsky’s [16] sociocultural theory further stresses peer interaction in the co-construction of knowledge.Together, these perspectives suggest that collaborative assignments deepen engagement and learning through real-time interaction. This pilot study applies those insights by replacing solitary, out-of-class papers with in-class group work. Although AI use was not measured, the in-class design was intended to reduce opportunities for outsourcing to tools like ChatGPT, which is a proactive decision to limit misuse. At the same time, research highlights challenges. Some students experience anxiety, uneven participation, or fear of evaluation in group settings [17,18]. These concerns stress the need for thoughtful implementation, ensuring benefits are realized while barriers are addressed.

1.2. Purpose

- This exploratory pilot study tested an instructional intervention designed to address two issues in higher education: the rise of AI-generated work and declining in-class participation. A portion of traditional out-of-class papers were replaced with collaborative in-class assignments to promote integrity, engagement, and learning outcomes. The intervention was implemented in undergraduate psychology courses and assessed using a combination of quantitative measures (e.g., attendance, grades, retention) and qualitative student feedback (e.g., perceived engagement, satisfaction, and instructional value). This mixed-method approach offers a comprehensive view of how classroom collaboration can support student success while reducing reliance on generative AI.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

- This study employed a posttest-only, non-equivalent control group design to test the impact of replacing individual written papers with collaborative in-class assignments on engagement and performance. Data were collected over four semesters (Fall 2023–Spring 2025) at a private Christian university in the Southwest. Two cohorts of students in the same psychology courses were compared: the pre-intervention group (Fall 2023–Spring 2024) completed traditional papers, while the intervention group (Fall 2024–Spring 2025) completed in-class collaborative assignments. Students were not randomly assigned, and no baseline measures were collected, consistent with the posttest-only design. Courses analyzed included Personality Psychology (two sections), Adult Development and Aging (one section), and Abnormal Psychology (one section), totaling eight sections across four semesters.

2.2. Participants

- A total of 812 undergraduates participated, drawn from three upper-division, face-to-face psychology courses at a private Christian university in the Southwest across four semesters (Fall 2023–Spring 2025). Enrollment by course was: Abnormal Psychology (≈55 per section; n = 220), Adult Development and Aging (≈68 per section; n = 272), and Personality Psychology (≈80 across two sections per semester; n = 320). Most students were juniors or seniors majoring in psychology, with some minoring or taking electives. Demographics were not formally collected, but institutional data suggest the majority were traditional-aged (18–21), full-time students. The student body is predominantly White, followed by Hispanic and Black students, with women comprising the majority and many identifying as Christian, consistent with the university’s mission.

2.3. Instructional Redesign (Intervention)

2.3.1. Overview of the Redesign

- The redesign replaced about half of the traditional individual papers with collaborative, in-class assignments, marking both a format shift and a move toward active, applied learning. Original papers emphasized independent research and reflection outside class, while the new activities focused on real-time collaboration, media analysis, simulations, and problem-solving during class sessions. Each activity was structured to foster peer interaction, deepen conceptual understanding, and limit opportunities for outsourcing to generative AI. Students engaged in authentic learning through discussion, joint decision-making, and shared problem-solving. All activities maintained the original objectives and aligned with existing rubrics to ensure continuity.

2.3.2. Collaborative Group Structure

- Students worked in self-selected groups of three to five, fostering autonomy, comfort, and peer connection. Each group submitted a final product graded with standardized, university rubrics assessing critical thinking, application of content, clarity, and integration of peer insights. Deliverables varied by course and included presentations, written reflections, case analyses, or worksheets. These were collected at the end of class and evaluated on par with the individual papers they replaced.For example, in Abnormal Psychology, an individual paper on models of abnormality became a collaborative media case study, where groups selected a film character and applied multiple perspectives (biological, psychodynamic, etc.) to build a diagnostic profile. In Personality Psychology, a paper on trait theories was redesigned as a group analysis project applying trait concepts to contexts such as leadership, workplace behavior, and relationships. In Adult Development and Aging, a dementia paper was replaced with an interactive “Dementia Workshop,” where students rotated through simulation stations, analyzed case studies, and completed comparative charts collaboratively.

2.3.3. Assessment of Collaborative Work

- Although overall course grades rose in the intervention semesters, assignment-level performance on collaborative tasks was comparable to traditional papers, suggesting gains were driven by greater participation and exam performance rather than grading leniency. Collaborative assignments awarded a single grade to all group members based on the final submission, reinforcing teamwork and shared responsibility. To promote equity and minimize social loafing, the instructor and instructional assistant circulated during sessions to provide feedback, monitor dynamics, and encourage contributions from all members. Peer accountability was emphasized through clear expectations, and students were encouraged to form groups with familiar peers. The same rubric used for the original papers was applied to the group assignments, ensuring consistency and preserving standards. These measures created a classroom environment grounded in collaboration, engagement, and integrity.

2.3.4. Instructional Consistency Across Sections

- All courses met twice weekly for 90 minutes (Tuesday/Thursday or Wednesday/Friday at 9:00 or 11:00 AM), ensuring equal instructional exposure and minimizing time-of-day effects. All sections were taught by the same instructor (the study author), controlling for differences in teaching style, grading, assignment design, and rapport. This consistency strengthens internal validity by making outcome differences more clearly attributable to the intervention.

2.3.5. Participation and Attendance

- During intervention semesters, students could complete assignments collaboratively in class or independently outside class. In practice, nearly all who attended chose the group format, with only about 1.5% working alone due to absence. Participation credit was tied to attendance, which included a brief lecture and assignment guidance, encouraging in-person engagement while allowing flexibility for absentees. Students were not informed that the assignments were part of a study but were presented as standard coursework, minimizing expectancy and novelty effects.

2.4. Data Collection

- Pre-intervention data (Fall 2023–Spring 2024) were drawn from institutional records, while post-intervention data (Fall 2024–Spring 2025) were collected in real time. All data were anonymized and analyzed in aggregate. The pre-intervention group included n = 410 students and the post-intervention group n = 402, with minor discrepancies due to uneven course offerings or partial records. Students with incomplete data were excluded. The impact of the intervention was assessed using multiple sources of data across four consecutive semesters, including:(a) quantitative participation data extracted from the LMS to capture weekly student engagement, (b) course-level GPA and DFW rates retrieved from institutional records, and(c) end-of-course surveys measuring students’ perceived engagement and satisfaction. These sources provided complementary insights into behavioral and performance indicators of engagement and outcomes. The use of multiple data sources allowed for methodological triangulation, which strengthens the credibility and validity of the findings [19]. By examining student behavior (participation), performance (GPA, DFW), and self-reported perceptions (surveys), the study ensured a multidimensional understanding of the intervention’s impact. Because of institutional policies, raw data are not publicly available through repositories such as OSF. However, summary data, assignment examples, and methodological details are provided in this manuscript, and additional information may be available upon request with university approval.

2.4.1. Weekly Attendance Records/Participation

- In-class participation was tracked as a behavioral measure of engagement. Courses met twice weekly for 90 minutes over 15 weeks (30 sessions total). Attendance alone did not earn credit; students had to complete a task such as a reflection, discussion prompt, or worksheet. Participation was recorded each session and counted toward the course grade (5 points per class, maximum 150 points). This standardized structure, used across all sections, reinforced accountability and provided a consistent measure of engagement for both pre- and post-intervention groups. On days with collaborative replacement activities, participation in those tasks fulfilled the requirement.

2.4.2. Final Course Grades

- Final course grades were collected at semester’s end to assess performance. Only students who completed the course were included. Grades were averaged by course and then across pre-intervention and intervention groups, allowing both course-specific and overall comparisons. These cumulative averages provided key indicators of learning and the impact of collaborative in-class assignments versus traditional papers.

2.4.3. Grade of D, F, and Withdraw (DFW) Rates

- DFW rates were calculated each semester to evaluate retention and persistence across the three psychology courses. Rates included students who officially withdrew, failed to meet requirements, or earned a final grade of D or F, expressed as a percentage of total enrollment at the institutional census date. In line with institutional reporting, D, F, and W grades were combined as indicators of non-passing or non-completion. Early withdrawals prior to the census date (e.g., after reviewing the syllabus) were not counted. Only students enrolled past census who later earned a D, F, or W were included. This method ensured consistency with institutional standards and allowed reliable comparison of DFW rates across pre- and post-intervention semesters. DFW data were used to examine whether collaborative in-class assignments influenced students’ likelihood of staying enrolled and completing the course.

2.4.4. End-of-Course Surveys

- End-of-course surveys were analyzed to assess satisfaction. The university administered these surveys online through the student portal at the end of each semester. Although voluntary, the instructor encouraged participation through in-class reminders and LMS announcements. End-of-course surveys were analyzed to assess satisfaction. The university administered these surveys online through the student portal at the end of each semester. Although voluntary, the instructor encouraged participation through in-class reminders and LMS announcements. The surveys remained consistent across the study and included quantitative Likert items and one open-ended prompt. For this analysis, the research focused on items aligned with the redesign’s goals of engagement and satisfaction:1. “The instructor created an engaging learning environment.”2. “The instructor demonstrated expertise.”3. “I would recommend this instructor.”Students rated each item on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). For qualitative analysis, we examined responses to the open-ended prompt, “Please share any feedback you might have.” These comments provided thematic insight into perceptions of the instructional format, course relevance, engagement, and classroom dynamics. End-of-course survey data thus offered both quantitative and qualitative measures to compare student satisfaction and engagement between pre- and post-intervention groups.

2.5. Data Analysis

- Data were analyzed from four semesters to assess the instructional redesign’s impact. Primary quantitative outcomes were final course GPA, in-class participation, DFW rates, and end-of-course satisfaction. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, percentages) were calculated for pre- and post-intervention groups. Of the initial N = 812 students, exclusions included incomplete participation data (n = 47; pre = 23, post = 24), grade data (n = 15; pre = 8, post = 7), and survey responses (n = 8; pre = 4, post = 4). Final analytic samples were: participation (N = 750; pre = 379, post = 371), grades (N = 797; pre = 404, post = 393), and surveys (N = 814; pre = 407, post = 407).Normality was assessed with Shapiro-Wilk tests and homogeneity of variance with Levene’s test. When variances were unequal, Welch’s t-tests were used; otherwise, Student’s t-tests were applied. Participation outcomes were analyzed at the course-section level (k = 8 sections: 4 pre, 4 post), while GPA, DFW, and satisfaction were analyzed at the student level. Independent-samples t-tests compared group means. For qualitative theme frequencies, Pearson chi-square tests were used when expected cell counts ≥ 5; Fisher’s exact tests were used otherwise. Effect sizes were calculated with Cohen’s d (continuous) and Cramer’s V (categorical).Given the study’s exploratory nature, analyses are reported without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Primary outcomes (DFW, GPA) were specified a priori; participation and satisfaction were treated as secondary exploratory measures. As a robustness check, Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction was applied.An a priori power analysis (G*Power 3.1) [20] indicated a minimum sample size to detect a small-to-medium effect (d = 0.30) with 80% power at α =.05 (two-tailed). Post-hoc power confirmed observed effects exceeded this threshold. Statistical significance was set at p <.05.

2.5.1. Ethical Considerations

- This study adhered to institutional ethical guidelines and FERPA regulations. Data analysed (attendance, grades, surveys) were archival and collected as part of routine instruction; all were deidentified prior to analysis. The instructional interventions used in post-intervention semesters reflected standard teaching practices, aligned with course objectives, and followed rubric-based assessments embedded in the LMS. No experimental treatments or deviations from normal pedagogy were introduced solely for research. Because the project involved secondary analysis of preexisting, deidentified educational data from established instructional practices, it qualified for IRB exemption under Category 1. Institutional policies for research with archival educational data were followed throughout.

3. Results

3.1. Participation

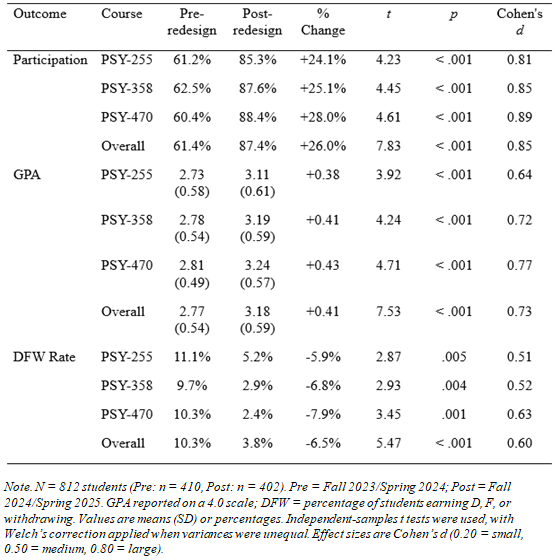

- Student participation increased significantly following the redesign, with overall rates improving by 26%. The largest gains were observed in PSY-255 and PSY-358, where participation rose steadily across the semester. PSY-470 also showed substantial improvement, with the largest percentage gain among the three courses. These findings suggest that the in-class collaborative format fostered more consistent engagement, particularly in the larger course sections. See Table 1 for a statistical breakdown of participation outcomes per course, both pre and post the redesign.

3.2. Academic Outcomes

- Course grades improved following the redesign, with GPA rising from 2.77 to 3.18, representing a moderate effect (d = 0.73). Each course showed significant gains, suggesting that the collaborative model consistently supported stronger performance across the curriculum.DFW rates also declined in all courses, with the largest reduction observed in PSY-470 (10.3% to 2.4%). Overall, DFW rates dropped 6.5 percentage points. These results indicate that the redesign not only improved academic performance but also enhanced student persistence. See Table 1 for a detailed statistical breakdown of these academic outcomes by course.

|

3.3. End-of-Course Survey Results

3.3.1. Likert Score Analysis

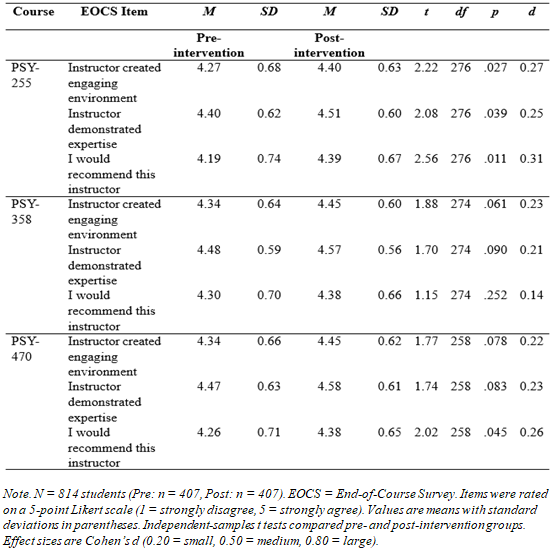

- Student satisfaction with instruction improved modestly but significantly across all courses. Ratings of instructor engagement, expertise, and willingness to recommend the instructor each increased by about 0.10–0.13 points, with small-to-moderate effect sizes (d = 0.22–0.28). Although these gains were statistically significant, consistently high baseline scores (4.25–4.45) suggest potential ceiling effects. Course-level results varied. PSY-255 showed the strongest response, with significant improvements on all three items (d = 0.25–0.31). PSY-470 demonstrated a significant gain for the “recommend instructor” item, while PSY-358 reflected positive but nonsignificant trends. Overall, four of nine comparisons (44.4%) were significant, and eight of nine effect sizes fell in the small range, underscoring consistent but modest improvements. See Table 2 for a complete breakdown of end of course survey results.

|

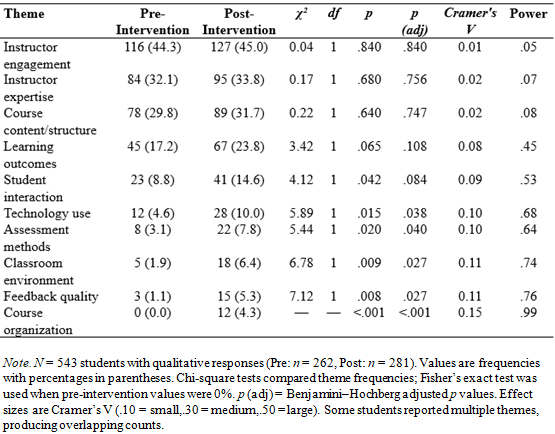

3.3.2. Open-Ended Response- Thematic Findings

- Analysis of open-ended course evaluation responses revealed consistent recognition of instructor engagement and expertise across both conditions, suggesting these qualities were stable regardless of instructional format. In the redesigned courses, however, students more frequently emphasized peer connection, collaboration, accountability, and a clear preference for in-class activities over traditional papers. They also described the redesigned courses as more enjoyable and as providing greater clarity of course content. Importantly, although not represented as a separate category in the aggregated chi-square analysis, 6.4% of students in the redesigned courses explicitly noted feeling less temptation to use AI tools, suggesting that the structure may have reduced opportunities for academic outsourcing. Overall, the qualitative findings support quantitative results by highlighting how collaborative in-class assignments not only maintained perceptions of instructor quality but also fostered richer engagement, stronger peer relationships, and enhanced academic integrity.

|

4. Discussion

- This pilot study provides preliminary evidence that replacing traditional take-home papers with collaborative, in-class assignments can enhance engagement, participation, and academic outcomes in undergraduate psychology courses. The most striking result was a 26 percent increase in participation, indicating a behavioral shift toward more consistent classroom involvement. This improvement was both statistically and practically meaningful, especially in a post-pandemic educational climate where disengagement and concerns about academic integrity are rising.The increase in participation aligns with Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), which highlights the motivational impact of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The redesigned format emphasized peer collaboration and reduced the demands of independent writing, which likely enhanced both motivation and connection. Although a slight dip in participation occurred in Spring 2025, rates remained well above pre-intervention levels, reinforcing the overall effectiveness and resilience of the model.A notable benefit of the redesign was reduced opportunity for AI misuse. Because assignments were completed during class time, students had fewer chances to rely on generative AI tools such as ChatGPT. Although AI use was not formally measured, several students shared feeling less temptation to rely on these tools. This suggests that collaborative structures may naturally mitigate integrity concerns associated with take-home tasks.Another impactful finding was the decline in DFW rates, which fell by 6.5 percentage points overall, representing a relative reduction of 34 percent. This suggests that the collaborative assignments promoted not only stronger performance but also greater persistence and retention. Peer accountability and real-time feedback may have been central in keeping students engaged and on track throughout the semester.Student feedback consistently emphasized real-time learning, peer connection, and a preference for in-class assignments over traditional papers. Together, these findings suggest that even modest instructional shifts, when grounded in psychological theory and responsive to student needs, can produce meaningful improvements in engagement, retention, and satisfaction.

4.1. Limitations

- Several limitations must be acknowledged. The absence of a formal control group restricts causal conclusions, and the study was conducted at a single private, faith-based university in the southwestern United States, which limits generalizability. Demographic data were not collected, preventing analysis of subgroup differences or moderating effects.Qualitative findings relied on self-report data from end-of-course surveys, which introduces response bias. Thematic analysis was conducted by a single investigator without interrater reliability checks, and only post-intervention comments were systematically coded. Informally, pre-intervention cohorts referenced general classroom atmosphere more often, while post-intervention students emphasized collaborative assignments, suggesting increased salience but requiring cautious interpretation.The shared-grade structure of group assignments also raises the possibility of social loafing. Although active instructor oversight and peer accountability strategies were used, future research should consider peer evaluations or hybrid grading rubrics to better capture individual contributions. Instructor bias is another limitation, as the researcher also served as the course instructor. While standardized rubrics and instructional assistants helped minimize this risk, replication by independent faculty is needed. Finally, while GPA increased, it is possible that the gains reflect higher engagement rather than changes in academic rigor.

4.1.1. Assumptions

- Several assumptions guided this study. First, it was assumed that student participation and academic records collected via the LMS and university systems were accurate and complete. Second, survey responses were presumed to reflect students’ genuine perceptions of the course experience. Third, while the study spans four semesters, it was assumed that course structure, instructor engagement, and grading rigor remained consistent aside from the intervention. Finally, it was assumed that external factors (e.g., pandemic recovery, institutional changes) had minimal influence on the results.

4.2. Future Research

- Future studies should expand to larger, more diverse samples and include matched comparison groups to strengthen causal inference and statistical power. Blinded grading or external assessment would provide a stronger test of true learning gains. AI use should also be measured directly to evaluate how course structures influence academic integrity. Expanding to online or large-enrollment courses would test scalability and adaptability across instructional settings. More structured qualitative methods, such as targeted reflection prompts, could also provide richer insights into student experiences.

4.3. Pedagogical Implications

- The findings highlight several practical considerations for instructors. Collaborative in-class assignments may help foster engagement, peer interaction, and persistence while reducing opportunities for academic dishonesty. Flexibility was built into this study, allowing students to opt out of group work if desired, though none reported doing so. This suggests general comfort with the structure, though future courses might gather targeted feedback from students who prefer independent work.Scheduling may also influence outcomes. Anecdotally, dips in attendance were observed on days when group activities occurred early in the week or on Fridays. Future iterations could explore how timing shapes engagement. More broadly, instructors might consider incorporating similar collaborative structures such as applied case studies, small-group analyses, or simulations to support deeper learning while balancing rigor with integrity.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML