-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2025; 15(2): 43-53

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20251502.03

Received: Oct. 20, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 10, 2025; Published: Nov. 25, 2025

Perceived Instrumentality as a Predictor of Academic Achievement of Secondary School Students in Mombasa County, Kenya

Rehema Nthenya Yaki, Edward M. Kigen, Samuel M. Mutweleli

Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Kenya

Correspondence to: Rehema Nthenya Yaki, Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The central problem of this study is academic underachievement of secondary school students over the years. Schools in Kenya, especially in Mombasa County are facing a big problem of poor quality grades which may be attributed to students’ failure to see the importance of current studying and its link to attainment of future aspirations. As a result, students are spending minimal time on school activities and giving up easily when faced with difficulties. The increased emphasis on academics by educators and parents has not resulted in increased effort in studying among students in Mombasa County. Poor quality grades have been consistently realized due to students’ inability to identify with academics and failure to connect current school performance to future outcomes. Therefore, the study sought to find out the extent to which perceived instrumentality predicts academic achievement of secondary school students. Academic self-esteem was hypothesised to mediate the relationship. The Future-Oriented Motivation and Self-regulation Theory was used to explain the study. This study used an ex post facto design. Purposive, stratified and simple random sampling were employed. Nine schools were purposively selected from a population of 49 public secondary schools from which a total of 542 students were selected in Mombasa County. Document analysis, self-report questionnaires was used. The questionnaire comprised the following scales: Approaches to Learning Survey to measure students’ perceived instrumentality; State Self-esteem Scale to measure students’ academic self-esteem. Students’ academic achievement was measured using examination records obtained from school. Data was analysed using quantitative approach. Instrumentality significantly and positively predicted achievement. Academic self-esteem mediated the relationship between grit and achievement. Findings help to inform policy makers, teachers, parents, and students on the importance of valuing academics for optimal academic achievement.

Keywords: Academic achievement, Perceived instrumentality, Utility value, Grit, Academic self-esteem

Cite this paper: Rehema Nthenya Yaki, Edward M. Kigen, Samuel M. Mutweleli, Perceived Instrumentality as a Predictor of Academic Achievement of Secondary School Students in Mombasa County, Kenya, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 43-53. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20251502.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Worldwide academic underachievement has remained a major concern among educators, parents and policymakers. Although education is seen as a route out of poverty [1] with teachers and parents encouraging students to work hard for a better future, recent trends show an increasing number of students performing below their potential. Research suggests that such underachievement may be linked to the way students perceive schoolwork and academic achievement [2,3,4] Schooling is future oriented yet, many students, while reporting that they value education struggle to perceive current schoolwork as meaningful, leading to low motivation and poor performance [4]. This mismatch is often accompanied by poor study habits despite valuing education for future gains [5]. Perceived instrumentality refers to the extent to which students believe that their current schoolwork and efforts are meaningful for achieving their valued long-term goals [6]. The Situated Expectancy Value Theory of Eccles and Wigfield [2] uses the term utility value conceptualized as the perceived usefulness of engaging in a task for current and future goals. Perceived instrumentality was conceptualized as comprising of grit and utility value. Grit as sustained effort and long-term goal commitment, even in the face of setbacks [7]. While utility value refers to how useful and important students perceive their current schoolwork to be in reaching their future goals [4]. Students who connect their present efforts and future goals are more likely to stay focused. The future Oriented Motivation and Self-regulation theory provides valuable insights on students’ motivation that plays a key role in shaping their achievement [4]. The theory explains that students’ motivation arises when they perceive a clear link between current academic efforts and personally valued long-term goals. This in turn fosters self-regulation, encouraging students to work hard and remain focused despite difficulties in order to attain this distal goals. The situated expectancy value theory explains that students’ engagement in academic tasks is determined by a combination of their expectancy of success and the value they place on the tasks which in turn enhances performance [2].

1.1. Statement of the Problem

- Academic underachievement in Mombasa County has been a major concern among educators and parents for many years. The problem of this study is that many students value education but do not like school nor value the content taught in school as much as adults and educators would want them to. This may be attributed to students’ failure to link current studying to attainment of future goals, which may result in minimal time and effort investment in school activities. Resulting in some students giving up easily when faced with difficulties. Minimal effort in schoolwork has negative implications on achievement in terms of poor grades which may limit their future aspirations. This is evidenced by KCSE results which for the period 2011-2016 have shown an average 52% of students’ getting D and E grades. Over the years an increase in low-performing students has been registered. Results obtained from Mombasa County for the period 2017-2023 show that 64% got D and below grades. Increased low grades suggests that a growing number of students struggled academically; hence, out of 16,632 candidates, 10,583 missed university [8].In addition to reporting poor school achievement, a report by National Council for Population and Development [9] revealed a 28% drop out in the County. If this trend continues, it will deny students the opportunity to join tertiary institutions or gain skills necessary for developing the economy of the County and the country in the long term. Thus, having a purpose for studying is important for form two students who are going through puberty and are at a time where they are starting to build foundation for their future. Research has been conducted on factors that influence students’ achievement in Kenya such as poor infrastructure, academic engagement, achievement motivation and self-regulation. Further, most studies have focused on present classroom goals of students, and cognitive factors like intelligence with little research done on future goals, instrumental motivation and non-cognitive factors such grit. Given that students pursue multiple goals while in school, a study on future goals and perceptions of school instrumentality is needed. In addition, most of the studies on perceived instrumentality, study time management and academic achievement have been done in Europe and USA using minority college samples thus creating the need to conduct a study in Kenya. Additionally, few studies exist regarding students’ perceived instrumentality, study time management and academic achievement. Therefore, this study aimed at establishing whether students’ valuing of academics results in effort investment in school work and better academic outcomes among form two secondary school students in Mombasa County, Kenya.

1.2. Purpose of the Study

- The study attempted to find out the extent to which students’ perceived instrumentality predict their academic achievement. The study aimed at establishing gender differences in perceived instrumentality, study time management and academic achievement of students in national and sub county schools. Further, the study investigated the extent to which academic self-esteem and school identification mediate the relationships.

1.3. Objective of the Study

- The objective of the study was: i. To find out the extent to which perceived instrumentality predicts academic achievement of secondary school students controlling for academic self-esteem.

1.4. Research Question

- The study was guided by the following research questioni. To what extent does perceived instrumentality predict academic achievement of secondary school students controlling for academic self-esteem?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Perceived Instrumentality and Academic Achievement

- Perceived instrumentality as a motivational construct has been studied to a lesser extend compared to proximal achievement goals. Multiple studies across age, methodologies and contexts however, provides strong evidence that instrumentality has a positive influence on effort regulation, academic self-esteem, and achievement [4,5,38,39]. This study draws on the Future Oriented Motivation and Self-regulation theory [4] that students’ instrumental believes are shaped by cultural context (peers, family background), and self-perceptions. Students who fail to link schoolwork to their future, or feel academic success is socially discouraged, may lose interest and disengage impairing performance.Empirical studies have shown that when utility value and grit are high students show greater persistence, effort on tasks, interest in schooling, engagement and achievement [4,5,7,40]. Instrumentality and achievement studies have largely focused on specific subjects. For instance, a study of 566 volunteers in a suburban high school in mid-South Oklahoma found that students who saw maths as useful for future gains had higher perceived ability, time, motivation and effort investment which explained 52% of self-regulation and 40% math achievement [10]. Similarly an investigation of 366 students (146 males, 212 females) among grade 10-12 students in a large Midwestern high school found that future goals, learning goals, performance goals and the goal of pleasing the teacher predicted effort and achievement in math more than task values and perceived competence goals. A negative association between perceptions of math as a male subject with girls’ achievement and persistence in the subject was reported. Instrumentality was associated with increased effort, persistence and use of mastery goals [11]. Further, a longitudinal of 10th grade students across six schools in South-eastern Michigan found utility value predicted English achievement reading time and career plans [12]. Apart from specific subjects, studies have also examined how instrumentality relates to time management, task motivation, learning and achievement. In Asia, China a study among 2,312 grade 7-12 high school students found that was grit significantly related to instrumentality which predicted intrinsic regulation and achievement. Grit mediated the achievement and instrumentality link [13]. In Singapore a survey of 2,775 high school students from 13 government schools examined how future goals and self-regulated learning were mediated by perceived utility value and perceived instrumentality. Schooling and education were found to influence students’ self-regulated learning, resulting in goal attainment [14]. A two factor model of 193 students from an academic-track high school in Korea found that endogenous instrumentality positively predicted course grades while exogenous instrumentality did not [15]. In Europe, Portugal, the effect of instrumentality and time management planning on achievement of 750 students in grade 7-9 aged 12-15 and reported a significant link between instrumentality and students’ achievement [5]. Studies on instrumentality in Africa are few, valuing of maths, intrinsic motivation and long-term planning were found to significantly predict grades using a sample from the 2011 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) of 38,806, 8th graders from Botswana, Ghana, Morocco, Tunisia and South Africa [16]. In Kenya, studies on grit and achievement are scarce. A correlational study among 379 form three students from 10 public high schools in Murang’a County was conducted to examine whether grit and personality traits predict achievement. A significant relationship with achievement was reported [17]. Similarly, the predictive power of grit on Chemistry achievement was done among 446 form three students in Etago Sub-County and revealed a significant and positive link to Chemistry achievement [18]. Research on instrumentality and achievement has received little attention with most research focusing on intrinsic motivation and achievement goals. For an adequate understanding of adolescents schooling experiences it is important to examine both classroom and future goals. Drawing on earlier evidence of instrumentality’s positive effects, [4,5,41,42,39] this study hypothesized that instrumentality would be linked to school engagement and grades. The study examined how instrumentality affects achievement, showing that academic success depends on self-perception. Prior research has overlooked academic self-esteem which is key in contexts where students may feel uncertain about their place in school.

2.2. Academic Self Esteem and Academic Achievement

- Academic self-esteem refers to the way students feel about themselves and how they self-evaluate their abilities in the academic domain [19,20,40]. Students’ achievement and overall self-esteem are closely linked as academic self-esteem shapes valuing and devaluing of the self. Those who feel confident possess high academic self-esteem while those who doubt their abilities have low academic self-esteem [20,41]. Students are more motivated when academic success matches their self-image and peers support them, however stigma and anxiety can lower motivation and achievement. In Europe, a survey study to establish whether academic self-esteem mediated the relationship between grades and psychological disengagement was done by Regner and Loose [21]. They used 183 North African French attending a priority education high school in France and found that grades were positively related to academic self-esteem and negatively related to discounting. This study used a minority group attending special schools in France. A study of 350 students from 20 classes in eight German schools found that classroom achievement impacts students’ academic self-esteem and being called a nerd. In high achieving classes, being labelled a nerd was strongly related to students’ academic self-esteem. Indicating that when peer norms devalue effort and academic identity, students may underuse effective study strategies despite recognizing their importance hindering achievement [22]. In the USA, an experiment of 93 high school students of colour in North Carolina reported a negative relationship between self-esteem and achievement. Further, high levels of overall self-esteem were reported despite low achievement. Lack of community support, devaluing of education and a few role models made it difficult for students to link current studying to future gains. Indicating that role models and instrumentality were necessary for students to excel [5,23]. Mixed results exist in Africa, a correlational study in Mombasa, Kenya on academic disidentification of 453 form three students in 12 high schools showed higher achievement among students who tied their self-worth to grades. A positive correlation of academic self-esteem and achievement was found which negatively correlated with discounting and devaluing. A negative relationship was reported between achievement and students discounting and devaluing of academics [24]. Similarly, a study of 14 academic heads and 525 students from private schools, 339 students and 7 academic heads from public schools on the relationship between self-esteem and KCSE performance, indicated a positive relationship between self-esteem and KCSE grades [25]. Another study of 421 form three students and 10 class teachers found fear of failure and negative evaluation were impaired students’ overall self-esteem affecting academic self-esteem and grades [26]. While in Nairobi County, using 480 form four students and 12 teachers, school type was reported to predict achievement, students from high achieving national schools had higher grades and self-esteem compared to those in extra county. High ability schools were found to have better grades because their students felt competent about their abilities compared to those in Extra County whose students had low self-esteem and grades [27]. Due to the scarcity of research, a study on this relationship was necessary. Studies have shown mixed results as students may feel good because they do well rather than do well because they feel good about themselves. The link between academic self-esteem and achievement is not clear. Results indicates that achievement often builds self-esteem rather than the reverse [28]. These mixed findings necessitate further research to clarify the mediating role of academic self-esteem on achievement.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- An ex post facto design was adopted for this study and was used to measure variables without manipulating them with an aim of allowing predictions of outcomes [29].

3.2. Research Variables

- The study measured the following variables: Perceived instrumentality (utility value and grit) measured at interval level as the independent variables. The intervening variable was academic self-esteem. The dependent variable was students’ academic achievement, average scores of all subjects in one term were converted into T-scores for comparison across the sample and measured at interval level.

3.3. Location of the Study

- The study was conducted in Mombasa County, a predominantly urban location with a heterogeneous population that provided a representative sample. Comprising of six Sub-Counties: Nyali, Mvita, Kisauni, Likoni, Jomvu and Changamwe. It was selected due to the 28% rate of dropouts [9] and its poor performance trends in KCSE. Statistics showed that 52% of students got D and below for the period 2011-2016. Moreover, the period 2017-2023 show that 64% got D and below grades [8]. Additionally, declining performance in public schools in the county is a worrying trend thus the need to examine underachievement in public schools.

3.4. Target Population

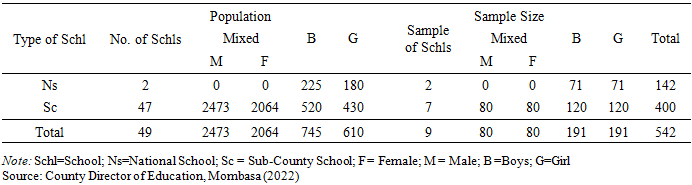

- The target population was 5,892 form two secondary school students from 49 public schools in Mombasa County [8]. The schools were selected and classified as either national or Sub-County schools then grouped into single sex or mixed school. Nine schools were selected, two national schools (boys’ and girls’ school) and seven Sub-County schools (single sex and coeducational). Form two students were selected because at this level they are supposed to choose subjects that will inform them on future goals. With academic demands increasing and a likelihood of decline in grades and interest in school at this level guidance is necessary.

3.5. Sampling Techniques and Sample Size

3.5.1. Sampling Techniques

- The study used stratified, purposive and simple random sampling procedures. Purposive sampling was used to choose Mombasa County public secondary schools from 6 Sub-Counties and form two students. The County has two national schools (boys and a girls’ school) which were purposely selected for the study. Stratified sampling was used to classify schools into national and Sub-County. Simple random sampling was used to select seven Sub-County schools by gender, two boys’ schools, two girls’ schools and three mixed schools using the lottery method. In total, nine schools were selected to participate in the study. Five hundred and forty two participants, were chosen using simple random sampling. The lottery method was employed to pick the participants from the class lists provided by class teachers. Papers with numbers assigned for the required sample and blank papers were folded and placed in a basket and mixed well. Students were instructed to pick at random, those who picked blank papers were requested to leave while those whose papers had numbers remained to complete the instrument. Additionally, nine class teachers were purposely selected for the study from the schools selected.

3.5.2. Sample Size Determination

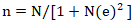

- The Yamane formula (1967) as cited in Israel

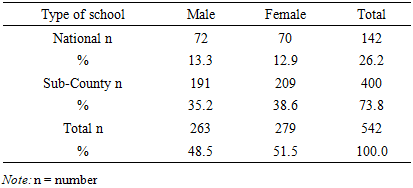

was used to calculated sample size. Where N= Population size and e = sampling error for the study. To compensate for nonresponse 30% was added to the sample [30]. The sampling frame is presented in Table 3.1 which indicates that a total of 542 respondents were sampled for the study.

was used to calculated sample size. Where N= Population size and e = sampling error for the study. To compensate for nonresponse 30% was added to the sample [30]. The sampling frame is presented in Table 3.1 which indicates that a total of 542 respondents were sampled for the study.

|

3.6. Research Instruments

3.6.1. Document Analysis

- Data on academic achievement was acquired from the students’ performance records. Aggregate scores of subjects examined at end of the term exams were used. This were transformed into T-scores to be able to compare them among the schools selected. Attendance records from class teachers register also provided students’ attendance data.

3.6.2. Questionnaire for students

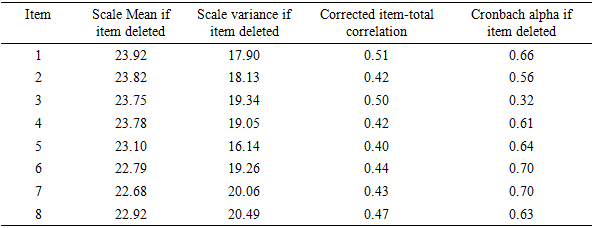

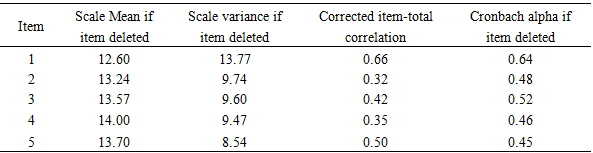

- The questionnaire was used to collect students’ information. Section A contained demographic characteristics (gender and school type) and Section B contained the following scales. i) Approaches to Learning Survey (ALS)Perceived Instrumentality (PI) subscale adapted from the Approaches to Learning Survey developed by Miller and others was used to measure students’ reasons for studying on a 5-point Likert scale [10]. The reliability index for the original study is 0.91 [31]. The items in the current study were changed to make them more general rather than specific referring to a class. From the original item the phrase ‘in this class’ was changed to ‘in school’ for example ‘the grade I get in this class will help me in achieving my future goals.’ was changed to ‘The grade I get in school will help me in achieving my future goals.’ Studies that used this instrument supporting the reliability and validity of the subscales [11,32].ii) The Grit-S Scale (G-SS)The Grit-S Scale of Duckworth and Quinn was used to measure perceived instrumentality on a 5-point Likert scale of 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (extremely like me). It consists of two sub-scales each with 4 items; Consistency of Interest with an alpha of .84 and Perseverance of Effort with an alpha.77. From the original item the phrase ‘setbacks don’t discourage me’ was changed to ‘I don’t give up easily.’ [33]iii) State Self-esteem Scale The Performance Self-esteem sub-scale of the State Self-esteem scale was used to measure academic self-esteem on a 5-point Likert scale of 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). All items that focused on general performance were adapted to reflect class performance [34].

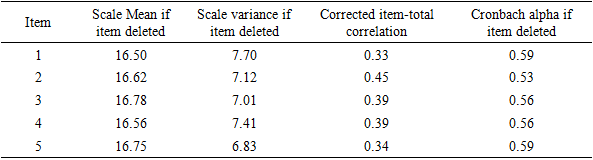

3.7. Reliability of the Study Instruments

- The internal consistency technique was used to assess reliability of perceived instrumentality, assessment of time management skills, grit, identification with academics and state self-esteem scales. Inter-item reliability was used to assess how items correlated among themselves in the scale and then compared with the original scale. The findings are presented next.a. The 5-item Perceived Instrumentality (PI) subscale adapted from the Approaches to Learning Survey (ATLS) was used to measure students’ perceived instrumentality on a 5-point Likert scale [10]. A reliability index of 0.62 was found. The reliability indices are presented in Table 3.2.

|

|

|

3.8. Validity of the Study Instruments

- Content validity of the instruments was ensured through peer review. Experts in Educational Psychology reviewed the items to establish their accuracy in measuring the constructs under study. Cohen and others contend that content validity can be established by expert judgement [29].

3.9. Data Collection Techniques

- The researcher administered the questionnaires to the students during normal class time. The researcher briefed students about the study and requested them to sign the consent form before inviting them to fill the questionnaires. Filled questionnaires were then collected.

3.10. Data Analysis

- Quantitative data was analysed using Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS). The following null hypotheses were tested at α =.05.H01: Perceived instrumentality does not significantly predict academic achievement controlling for academic self-esteem.

4. Findings, Interpretation and Discussion

- The purpose of this study was to establish the extent to which perceived instrumentality predicts students’ academic achievement. This section therefore contains the analysis of data collected. Data are analysed in line with the following objective.i. To find out the extent to which perceived instrumentality predicts academic achievement controlling for academic self-esteem.

4.1. General Information

- The data for analysis came from 250 male and 270 female students out of the 520 that was sampled for the study indicating a return rate of 95% as presented in Table 4.1.

|

4.1.1. Demographic Information

- Results from Table 4.1 indicate that schools were sub-divided into national and Sub-County categories. Mombasa County has two national schools (girls and boys) both were sampled in addition to seven Sub-County schools. Results from Table 4.1 indicate that majority of the sampled population was obtained from seven Sub-County schools. Overall sample consisted of 263 (38.5%) male and 279 (51.5%) female.

4.2. Demographic Information

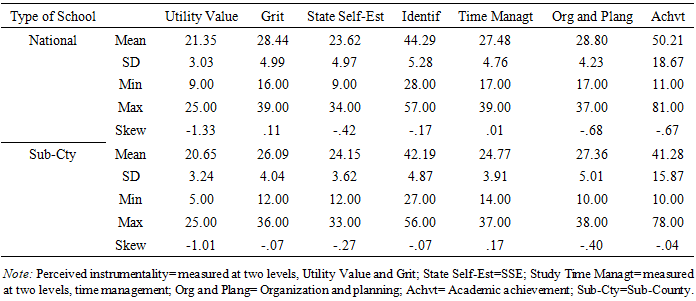

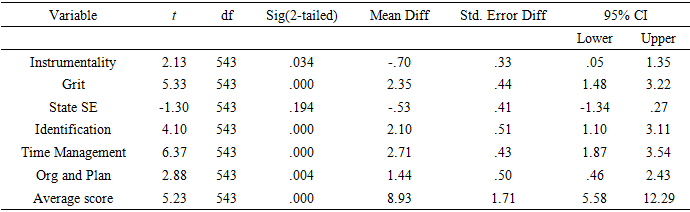

- There are only two national schools in the county, results from Table 4.1 indicate that majority of the sampled population was obtained from seven county schools. To establish whether measured variables differed by type of school, means and standard deviations were computed as presented in Table 4.2. Findings indicate that students in national schools reported higher means in all measured variables with the exception of state self-esteem. Additionally, whereas participants from both national and county schools reported low scores in time management, only students from national schools reported lower scores in grit. Students in county schools also reported higher scores on state self-esteem despite their low academic achievement. This finding implies that poor achievement in county schools did not affect their state self-esteem.

|

|

4.3. Results of the Study

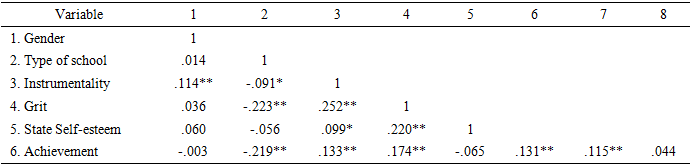

- To establish linear relationships and collinearity of measured variables, a correlation matrix was computed. No large correlations were found. Gender, state self-esteem and organisation and planning were not significantly related to academic achievement. A significant and negative relationship was found between type of school and academic achievement, indicating that students in County schools were more likely to report lower achievement compared to those in national schools. Higher instrumentality, grit, positively correlated to academic achievement. Female students were more likely to report higher instrumentality compared to male students; while students in County schools were more likely to report lower instrumentality, grit, self-esteem, and academic achievement. These findings were reported in Table 4.4.

|

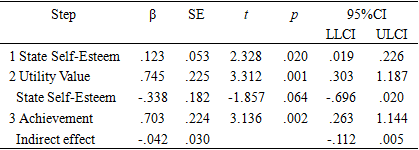

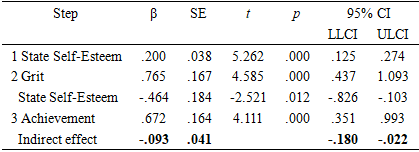

4.4. Prediction of Instrumentality on Academic Achievement Controlling for State Self-esteem

4.4.1. Descriptive Analysis

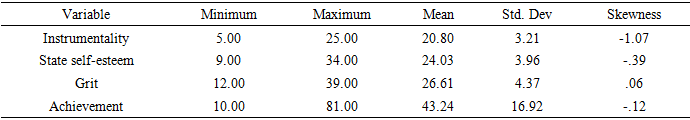

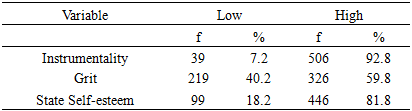

- Means and standard deviations of variables were computed and presented in Table 4.5. Perceived instrumentality was measured at two levels, that is, instrumentality and grit. Findings indicate that students reported higher scores on instrumentality, state self-esteem, and academic achievement while low scores were reported on grit.

|

|

|

|

5. Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Summary

- The study set out to establish the extent to which perceived instrumentality predicts academic achievement of high school students in Kenya. Academic self-esteem was the intervening variables that was tested for mediation. It was carried out among a sample of 542 students in Mombasa County, Kenya. Document analysis, self-report questionnaires was used in data collection. Findings show that instrumentality positively predicted achievement. Whereas academic self-esteem did not mediate the relationship between instrumentality and achievement. Grit positively predicts achievement, but this link was mediated by academic self-esteem. This seems to confirm that sustained feelings of self-worth predict long-term outcomes. In fact, other than type of school, only grit significantly contributed to achievement. Sadly, being in a Sub-County school predicted poor achievement with significant gender differences reported in instrumentality in favour of girls.

5.2. Conclusions

- From the findings, we can conclude that students perform better when they value education and feel supported by significant others. However, findings also illustrate that despite valuing education, majority of the students strive to protect their self-esteem at the expense of learning. It has been established that most students are underachieving due to fear of academic failure and the fact that they are not prepared to fail, consequently interfering with the effort required to be successful in academics. It is evident that students with more passion and perseverance in the pursuit of long-term goals believe more in their academic abilities, which has a strong connection with academic achievement. Such students feel like learning is a part of the self and are more willing to keep on learning, forgo their short-term wants, persevere and remain motivated even when faced with difficulties or when learning is not enjoyable in order to attain their valued future educational goals. As a result, they perform better than those who give up when faced with setbacks. Findings also shows that academic tasks are valued by most students but, they find them boring, tedious, and uninteresting hence low achievement.Findings lead to the conclusion that social context has implications for students’ instrumentality, performance. Students who have supportive peers are highly motivated, not easily bored and do well in school. Additionally, support by significant others is linked to engagement in schoolwork. However, students are receiving less support from parents and teachers in high school which may lower their engagement in school affecting their engagement in academics and achievement. Students’ self-esteem is also affected when their performance does not match societal expectations, often resulting in reduced engagement in academics. Since parents’ value scholastic competence and discipline, whereas most adolescents’ value social, physical appearance and athletic competence, it is important that students balance between social and academic activities.

5.3. Recommendations

- Findings lead to the following recommendations:

5.3.1. Recommendations for Research

- The following are recommended for further research:1. This study adopted survey methodology. It will be important to carry out similar studies using experimental methods (e.g., randomised controlled trials) to establish the effect of instrumentality on achievement.2. Since the study established that school type influence learners’ instrumentality, carrying out research on how school type enhances or weakens instrumentality, focusing on national, extra-county, county, sub-county schools and private schools may help predict achievement.

5.3.2. Recommendations for Practice

- For practice, the following are recommended:1. Teachers may need to use more interactional approaches and career-linked teaching to enhance instrumentality of schooling.2. Teachers should nurture the utility value of schooling through peer support groups of converging interests. 3. Policy makers need to incorporate the learning of multiple skill sets apart from regular schoolwork in the curriculum.4. Curriculum developers and teachers need to make learning relatable through career linked teaching.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML