-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2024; 14(2): 35-48

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20241402.01

Received: Mar. 17, 2024; Accepted: Apr. 7, 2024; Published: Apr. 13, 2024

Gender and Explanation of the Risk of Infidelity Based on Sexual Dissatisfaction in the Couple: A Psychometric Study

Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo1, Sylvestre Nzeuta Lontio2

1Department of Philosophy and Psychology, University of Maroua, Maroua, Cameroon

2Department of Philosophy-Psychology-Sociology, University of Dschang, Dschang, Cameroon

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Despite the fact that the literature has invested in research into the determinants of infidelity in couples, highlighting in particular the role of partners’ sexual dissatisfaction, little is known about the risk of infidelity. This risk, which lies before infidelity, consists of an intention to violate the norm of exclusivity in romantic relationships. To the best of our knowledge, not only is this risk little studied, but also the standardized psychometric tools capable of measuring it have not yet been constructed; hence the methodological gap that the present study identifies and aims to fill by constructing and validating a psychometric method for evaluating this construct (Study 1). Furthermore, following in the wake of work establishing the link between sexual dissatisfaction and infidelity, this study also aims to test the hypothetical link between sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity, in a comparative perspective between men and women (Study 2). Regarding study 1, the exploratory test (EFA) carried out with 205 participants reveals a reliable unifactorial structure of 6 elements of the constructed psychometric method. The confirmatory analysis of the measurement model, using the structural equation method (CFA-SEM), carried out on a sample of 313 participants confirms the factorial structure which fits perfectly to the data. Tests of factorial invariance according to gender (n1=219 women; n2=94 men) reveal structural equivalence between the groups. Regarding study 2, two hypotheses were tested with 174 participants (n1=46 women; n2=128 men). The regression results confirm the fact that sexual dissatisfaction significantly explains the risk of infidelity (hypothesis 1). Multigroup regression, for its part, provides support for the idea that sexual dissatisfaction explains risk of infidelity more among women than among men (hypothesis 2).

Keywords: Sexual dissatisfaction, Infidelity, Risk of infidelity, Gender, Confirmatory structure, Factorial invariance

Cite this paper: Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo, Sylvestre Nzeuta Lontio, Gender and Explanation of the Risk of Infidelity Based on Sexual Dissatisfaction in the Couple: A Psychometric Study, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 2, 2024, pp. 35-48. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20241402.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In many societies, fidelity is considered a fundamental value of the couple. However, in Europe in particular, the requirement for fidelity evolved significantly from 1980 to 2000 (Schweisguth, 2010), noting that it is difficult to have long-term romantic relationships devoid of transgressions (Grøntvedt et al., 2020). The literature that is interested in these transgressions is almost exclusively focused on their manifest aspects; with particular emphasis on their causes, objectively observable and measurable manifestations and consequences on married life (Aldahadha & Al-Momani, 2023; Cramer et al., 2008; Banfield & McCabe, 2001; Buss & Shackelford, 1997; Glass & Wright, 1992; Romero-Palencia et al., 2007; Whatley, 2006; Yeniceri & Kokdemir, 2006). As a result, we know little about the non-manifest (latent) aspects of this phenomenon, that is to say the risk or intention of infidelity, in a context where, however, the intention is theorized as one of the determinants of behavior (Ajzen, 1991), since it indicates to what extent individuals are ready to initiate actions or make efforts to adopt a behavior.The concept of risk of infidelity (Dallaire, n.d.) can be used to designate the intention of infidelity. It represents the potential to be unfaithful or to be deceived, that is, to commit or suffer infidelity; which therefore differentiates it from infidelity which constitutes the behavior of an individual who has committed the act. Indeed, the risk of infidelity relates to an individual’s intentions, thoughts, desire or predisposition to commit infidelity (Fincham & May, 2017; Urganci & Sevi, 2019). For this research, this risk concretely refers to the will or desire to maintain an extradyadic relationship. The individual who presents a risk of infidelity is not necessarily unfaithful. He is just likely to commit acts of infidelity. From this perspective, the analysis of the risk of infidelity lends itself to the analysis of the intentions or the latent or non-objective elements which underlie the materialization of infidelity; hence the fact that Buss and Shackelford (1979) speak of it as a susceptibility to infidelity. According to these authors, infidelity susceptibility refers to self-report of anticipated intention to infidelity, which can be a reasonable indicator of infidelity risk. It is esteemed by the fact of: « flirting with someone else, passionately kissing someone else, romantically dating someone else, having a one night stand with someone else, having a brief affair with someone else, and having a serious affair with someone else » (Buss & Shackelford, 1979, p. 196). Thompson (1983) reviews the work on extramarital relations among men and women and report that the estimation of susceptibility to infidelity vary from 40 to 76% over the course of a marriage. As an illustration, in 2006 in France, 24% of women compared to 34% of men declared having been involved in at least one extramarital relationship (Garcia, 2018). Kato (2021) reveals that in Western cultures, rates of marital infidelity are generally higher than in Asian cultures. For example, Japanese people have unfavorable attitudes towards extramarital sex; hence the infidelity rates of men and women in Japan standing at 15.9% and 15.6% respectively (Funaya et al., 2006 cited by Kato, 2021). In addition to these numerical data, the literature reports that Japanese men would be more upset than Japanese women about the sexual infidelity of their partner, while the latter would be more upset than the first cited about the emotional infidelity of their partner (Kato, 2021).Despite efforts to conceptualize the risk of infidelity, this construct still remains very little known in the literature relating to infidelity. One of the reasons for this situation relates to the absence of a psychometric measure that can serve as a reference measure. In turn, this absence of instrument could be justified by the slightest effort to conceptualize this notion; because to evaluate a construct via a psychometric measure, it is imperative to conceptualize it in order to determine its indicators (Churchill, 1979). In fact, work on infidelity has focused on the attitudes towards infidelity, the study of its obvious aspects, the tolerance towards it, its causes and consequences or the perception of deceived people (Aldahadha & Al-Momani, 2023; Cramer et al., 2008; Banfield & McCabe, 2001; Buss & Shackelford, 1997; Glass & Wright, 1992; Romero-Palencia et al., 2007; Whatley, 2006; Yeniceri & Kokdemir, 2006). In other words, the literature pays little attention to the risk of infidelity; hence the interest of the present research in this poorly documented construct, particularly because of the potential link it could have with manifest infidelity. It aims to: 1) construct and validate a psychometric method for assessing the risk of infidelity in romantic relationships; and 2) test the hypotheses relating to the links between sexual dissatisfaction and risk of infidelity among men and women.

1.1. Infidelity in Romantic Relationships

- In a romantic relationship, infidelity presents itself as a behavior that transgresses the exclusivity of romantic relationships. It is a negative and morally unacceptable social fact and a transgression of the norms of the marital relationship that prevails in several societies, including traditional societies (Rokach & Chan, 2023; Van Hooff, 2017). This behavior can be romantic (virtual or face-to-face), sexual (e.g. engaging in sexual behavior with an extradyadic partner) or emotional (e.g. developing deep and intimate feelings for an extradyadic partner; trusting them; share one’s deepest thoughts with another; fall in love with another; be vulnerable in front of another; be more committed to another partner). Infidelity can be combined (sexual and emotional) or accompanied by flirting (Leeker & Carlozzi, 2014; Rokach & Chan, 2023; Weiser et al., 2014). In this sense, the analysis of the definitions of infidelity indicates that the unfaithful partner often fails to develop romantic feelings towards his usual partner, to honor and support him (Bernard, 1974). Furthermore, infidelity behaviors involve a high degree of discretion and concealment (Pittman & Wagers, 2005; Rokach & Chan, 2023). They occur outside of the primary relationship, when extradyadic behavior is viewed by the romantic partner as a transgression or violation of relationship norms (Rokach & Chan, 2023; Thompson, 1983). In the strict context of marriage, infidelity is commonly called adultery. It undermines normal intimate relationships involving exclusive commitment and a level of investment oriented exclusively towards the partner. The literature compares trends towards infidelity in couples (Birnbaum et al., 2019; Eindor et al., 2015; Garcia, 2018). Indeed, the degree of permissiveness of women regarding extramarital sexual relations is relatively lower than that of men. As an illustration, in 2006 in France, 24% of women compared to 34% of men declared having experienced at least one extramarital relationship (Garcia, 2018). However, one study indicates that only women who engaged in past extradyadic relationships report experiencing higher rates of sexual fantasies (Hicks & Leitenberg, 2001). The literature also notes that among men, the level of stress relating to the sexual infidelity of their partner is higher than that of women. Furthermore, women are less accepting of their partner’s emotional infidelity than men (Bozoyan & Schmiedeberg, 2022; Labrecque & Whisman, 2020). Furthermore, behaviors perceived as unfaithful in nature (e.g. having extradyadic sexual relations and kissing someone other than the usual partner with emotional involvement) are considered acts of infidelity (Bendixen et al., 2018; Bozoyan & Schmiedeberg, 2022; Choupani et al., 2021). In the same vein, Labrecque and Whisman (2020) reveal that women and men experience sexual infidelity more painfully than emotional infidelity. Research also reports that the perception of internal threats to a relationship induces less sexual desire for the partner (Birnbaum et al., 2019); which predicts greater attraction to other partners and consequently induces extramarital sex.The factors that determine infidelity behavior among individuals differ depending on gender (John, 2006). Predictors of infidelity are personality variables (high narcissism and low conscientiousness), including tendency towards sexual arousal, high psychoticism, relative partner value (the relative desirability of partners), and concerns about sexual performance among men (Buss, 1991; John, 2006; Symons, 1987). Other predictors of infidelity relate to frigidity, sexual obsession, relational contexts and recurring sources of conflict and sexual satisfaction (Buss & Shackelford, 1997). The absence of happiness provided by sexual activity is a determinant of infidelity in women, because love is a source of pleasure and fulfillment (Rokach & Chan, 2023). In this vein, Dallaire (n.d.) puts forward the idea that the probability of the appearance of infidelity behaviors is a function of the dissatisfaction of certain needs, like sexual pleasure. The latter would predispose individuals to infidelity. It is assessed by the quality of the sexual relationship. Thus, when sexual behavior is judged unsatisfactory, infidelity is possible; which would make the marital relationship less reassuring and fulfilling (Glass & Wright, 1992). The analysis of marital dissatisfaction indicates different manifestations in men and women (Allen et al., 2005). In fact, unfaithful men report more sexual satisfaction in their relationship than unfaithful women. The partners’ degree of investment in the relationship and the perceived quality of alternatives also play a role in infidelity. Despite the fact that infidelity is observed more among men than among women, it is difficult for men to develop affects towards extramarital partners (Fincham & May, 2017; Maykovich, 1976). Indeed, even if the results of Scheeren et al. (2018) show similarities in infidelity behaviors between men and women, it remains that men are more involved in sexual extramarital relationships linked to the need for sexual diversity and women in emotional extramarital relationships (Wróblewska Skrzek, 2021). These affects are considered catalysts for the risk of infidelity; an object little documented in the literature on infidelity.

1.2. The Present Research: The Risk of Infidelity in Romantic Relationships and Its Measurement

- Work that analyzes the factors underlying the risk of infidelity focuses a lot on personal factors; hence the fact that relatively little is known about how relational dynamics induce this risk. Some studies have theoretically examined intentions or the risk of infidelity at the relational level and have come to the conclusion that reduced commitment to the partner and sexual dissatisfaction explain this risk (Allen et al., 2005; Dallaire, n.d.). Other studies highlight that simply imagining infidelity motivated by sexual dissatisfaction provokes more strong negative emotions than imagining infidelity due to emotional dissatisfaction (Hedrih, 2023). But, they did not empirically evaluate the relationship between sexual dissatisfaction and infidelity intentions in men and women; hence the interest of this research. It is in the perspective of the work of Dallaire (n.d.) who suggests that the probability of unfaithful behavior appearing among partners is all the greater if certain needs (emotional, sexual, or security for example) are unsatisfied. However, until now, this hypothesis has not been the subject of an empirical test with samples of women and men living in a romantic relationship. In other words, to date, the specialized literature does not provide evidence of statistical validity of this hypothesis within these two groups, especially since there is no standardized psychometric instrument in the literature to assess the risk of infidelity. Moreover, if the risks of infidelity due on the one hand to the sexual dissatisfaction of men and to the emotional dissatisfaction of women on the other hand are well documented (Bozoyan & Schmiedeberg, 2022; Rokach et al., 2023), it remains that little is known about the role of women’s sexual dissatisfaction on the risk of infidelity, as well as the differences between men and women in how sexual dissatisfaction impacts the risk of infidelity.

2. Overview of Studies

- In view of all the above, the objective of the present study is twofold. First of all, due to the absence in the specialized literature of a psychometric method for assessing the risk of infidelity, this study proposes to construct and validate one by drawing inspiration from the measure developed by Dallaire (n.d.) for the purposes of his study (Study 1). Then, we propose to empirically test the hypothesis of the link between sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity in a comparative perspective between men and women (Study 2).

2.1. Study 1

- To assess infidelity in romantic relationships, several scales have been constructed. We can cite, among others, the Attitudes toward Infidelity Scale (Whatley, 2006), the Infidelity Expectations Questionnaire (IEQ) (Cramer et al., 2008), the Measures of Extramarital Involvement (Glass & Wright, 1992), the Susceptibility to infidelity (Buss & Shackelford, 1997), the Extra Relationship Involvement Questionnaire (ERIQ) (Banfield & McCabe, 2001), the Infidelity Questionnaire (INFQ) (Yeniceri & Kokdemir, 2006), and the Multidimensional Infidelity Inventory (IMIN) (Aldahadha & Al-Momani, 2023). Despite their relevance, all of these instruments have the same limitations, linked in particular to the fact that they cannot be used as measures to assess the risk of infidelity.The only psychometric measure that seems to be appropriate for assessing the risk of infidelity is the scale of the risk of infidelity or the risk of being cheated on by a partner (Dallaire, n.d.). However, due to the fact that the risk of infidelity and the risk of being cheated on by a partner are two distinct constructs, the content validity of this measure is questionable. Similarly, the conceptual analysis of the risk of infidelity indicates, for example, that one partner’s complaints about the other partner’s refusal to have sex, sources of irritation and upset within the couple or attacks of jealousy could explain an increased risk of infidelity (Buss, 1989, 1991; Buss & Shackelford, 1997). However, these elements are more predictors than indicators of the risk of infidelity. In the same vein, the examination of certain items of Dallaire (n.d.) test, for example item 1 (“Is one of the two possessive or jealous?”), item 3 (“Does one of them get pitied by their friends or parents?”) and item 14 (“Has one of them suddenly become more irritable?”), reveals that this test has a problem of content validity linked to the conceptualization of the risk of infidelity. Furthermore, Dallaire (n.d.) himself points out that his test has not undergone any validation according to the standards generally established in scientific methodology and that it is based solely on his clinical expertise. This underlies the idea that the validity of the items in this test rests solely on the subjectivity of its author and not on proof of validity respecting known standards in psychometrics. Therefore, there is no scientific evidence of the reliability of this test in measuring the risk of infidelity; hence the need to evaluate the internal structure of the constructed measure and to select the items which effectively measure the construct investigated. This is why the present study explores the factor structure (sample A) and tests the confirmatory factor structure and invariance (sample B) of the risk of infidelity scale proposed by Dallaire (n.d.).

2.1.1. Method

2.1.1.1. Participants

- Two samples were used to achieve the objective of this study. The first allows us to explore the factorial structure of the scale and the second to confirm this structure and test its invariance. For a psychometric study, a large sample size implies lower measurement errors and more stable factor loadings, replicable factors, and results generalizable to the true population structure (Osborne & Costello, 2004). This is why it is recommended to have a range of 200 to 300 participants to carry out factor analyzes (Guadagnoli & Velicer, 1988; Comrey, 1988).(i) Subsample 1 For the exploratory factorial test, two hundred and five (N=205) men (n1=103) and women (n2=102) of Cameroonian origin agreed to participate voluntarily in the study. They are 23.66 years old on average (SD=5.89). These are individuals involved in a romantic relationship at the time of data collection. From the point of view of research ethics, the confidentiality of their responses was guaranteed.(ii) Subsample 2 To establish evidence of confirmatory validity and test the invariance of the risk of infidelity scale, three hundred and thirteen (N=313) men (n1=94) and women (n2=219) of Cameroonian origin agreed to complete the questionnaire, without compensation. Their average age is 23.26 years (SD=4.07). Like the members of subsample 1, they were involved in a romantic relationship at the time of data collection. They received the same guarantees as their counterparts in subsample 1 regarding the confidentiality of their responses.

2.1.1.2. Measurements and Procedure for Constructing the Risk of Infidelity Scale

- The scale validated in the present research draws heavily on the risk of infidelity test proposed by Dallaire (n.d.). This fifteen (15) item test assesses this construct using a four (4) points’ response format: 0 (Rarely), 1 (Occasionally), 2 (Often) and 3 (Almost all the time). For example, item 1 suggests that: “Is one of the two possessive or jealous?”, while item 10 states that: “Does one of the two react more intensely during arguments? » This research reformulates these statements which are in the interrogative form by putting them in the affirmative form. For example, item 7 which asked that: “Is one of the two absent more and more often or does he arrive late more and more often?” becomes: “I am absent or arriving more and more late for appointments with my partner.” Item 13 which proposed that “Would one of the two want more commitment from the other (marriage, house, child, etc.)?” becomes “I have the feeling that my partner does not want to commit to a long-term relationship.” These items are rated on a seven (7) points Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The objective of this measure is only to assess the risk that an individual is unfaithful. It is therefore not interested in the risk of being deceived by her partner. As a result, all 15 items were reformulated. The content validity of the new measure was ensured by submitting it firstly to the expertise of two (2) researchers in social psychology and secondly to a sample of participants (Boateng et al., 2018). At the end of this phase, ten (10) items were retained for the exploratory validation phase of the scale. On the other hand, five (05) items were deleted, due to their disconnect with the construct evaluated (e.g. “I react more intensely during arguments.”; “I have the feeling, the impression or the intuition that something is happening.”). This scale was self-administered in this exploratory phase of the study. After providing information relating to their gender and age, participants were asked to indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement on each item by checking or circling the number that closest to their intention of infidelity. We specify that the scale used in the confirmatory factorial validation and measurement invariance testing phases is the reduced version of the scale obtained during the exploratory phase. It is written in the French language.

2.1.1.3. Data Analysis Procedure

- This study used JASP.17.1 statistical software to calculate descriptive statistics (M; SD) and test the exploratory factor structure of the risk of infidelity scale. In psychometrics, commonly used methods for determining the number of factors to retain include a scree plot (Cattell, 1966), the variance explained by the factor model, and the factor loading model (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011). Thus, to understand the latent (internal) structure of the set of items of the scale and to what extent the relationships between these elements are internally consistent, the methods of Exploratory Factor Analyzes (EFA) and the Varimax orthogonal rotation method were used as methods of extracting factors. The KMO (Kaiser, 1974) and Bartlett chi-square indices were also determined in order to estimate the level of sampling adequacy and the possibility of factoring the items of the scale. These methods made it possible to summarize and reduce the structure of the risk of infidelity scale. To give the most credence to the reliability of the scale, the present research followed the recommended ideal procedure (Boateng et al., 2018), which is to develop the scale on a sample A, whether cross-sectional or longitudinal, then to test it on an independent sample B. The reliability indices were estimated in the two samples (A and B) of this study. JASP.17.1 software was used to analyze the confirmatory factor structure and invariance of the risk of infidelity scale. In this sense, the overall fit of all confirmatory factor analysis (CFA-multigroup) models was determined using the scaled chi-square goodness-of-fit test. This test was supplemented by alternative fit indices (Kline, 2016), including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI≥.95) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI≥.95, reasonable fit), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA≤.08, reasonable fit) and the Standardized Root Mean square Residual (SRMR≤.06, acceptable fit). Comparison of relative fits of multi-group CFA models using scaled Chi-square difference tests was performed. However, this test depends on the sample size and the Δχ2 is often statistically significant when the sample size is above 300 participants (Kline, 2016). The ΔCFI was estimated (Cheung & Lau, 2012; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). A value of ΔCFI<.01 indicates support for the more parsimonious model constrained by equality. All this made it possible to establish proof of configurational, metric and scalar invariance of the risk of infidelity scale.

2.1.2. Results

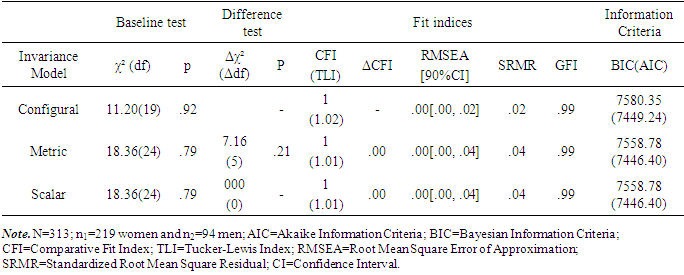

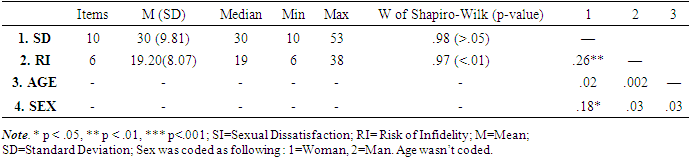

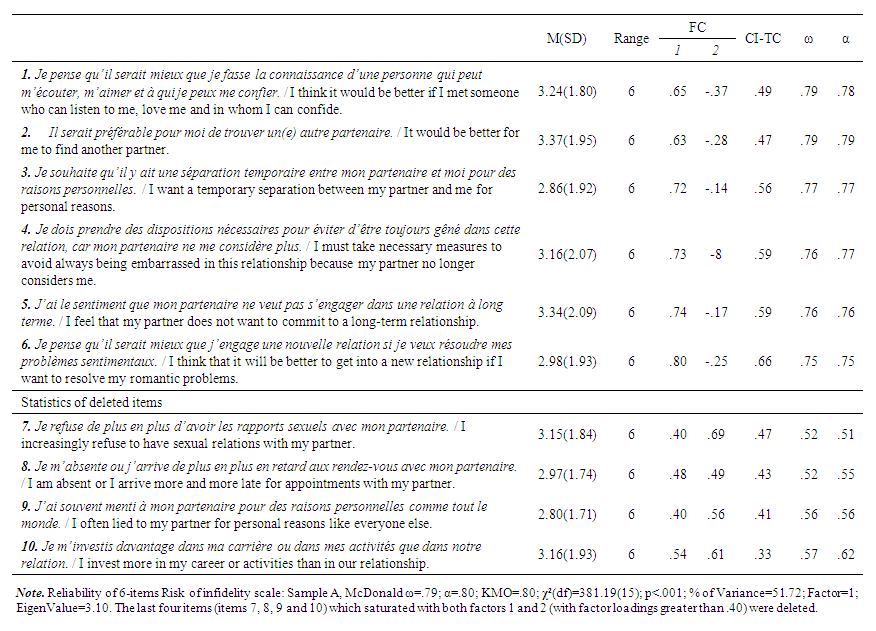

- The results of this study focus first on the exploratory factorial structure (See Figure 1), the description of the items and their reliability (See Table 1). Then, they focus on confirmatory factor analysis (See Figures 2 and 3). Finally, they test the invariance of the developed measure (See Table 2).

2.1.2.1. Exploratory Analyses

- After exploratory analysis, of the ten (10) manifest variables (items) making it possible to capture the risk of infidelity introduced into the analysis, 6 were retained on the basis of their factor loadings relatively greater than .40 (Nunnally, 1978; Raykov, 2011). These factor loadings vary between .63 and .80. The four (4) deleted elements (See Table 1) presented cross-factorial loadings, meaning that the loadings of these elements were not unique on the individual latent factor (Boateng et al., 2018). The items retained have average distributions ranging from 2.86 (item 3) to 3.37 (item 2), with dispersions ranging from 1.80 to 2.09. This reveals that they strongly contribute to the assessment of the risk of infidelity. The overall reliability of the scale saturates at .79 according to the McDonald method (McDonald, 1999) and at .81 according to the Cronbach method (Cronbach, 1951). That of the elements varies between .75 (item 6) and .80 (items 1 and 2), with inter-item relationships ranging from .47 to .66. These results indicate that the 6 elements retained for the assessment of the risk of infidelity form a coherent whole constituting a uni-factorial measurement model. Thus, the correlation matrix can be factorized, because the Bartlett statistic is significant (χ²(df)=238.822(15), p<.001) and the KMO statistic (Kaiser, 1974) reveals a strong validity of the factorial model (KMO=.79). The estimated shared variance of responses between multiple items is 50.61%.

| Table 1. Descriptive (M(SD), Median), factorial loadings (FC), Inter-items correlation (CI-TC) and items reliability (ω and α) Statistics (sample size A, N=205) |

| Figure 1. Item collapse plot |

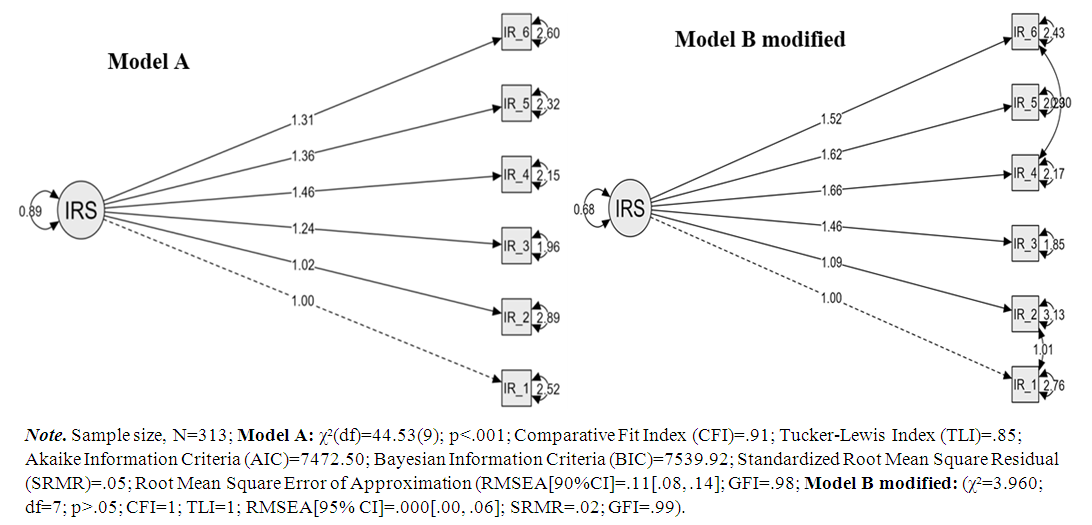

2.1.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Measure

- The results of this analysis come from sample B. The preliminary test to verify the reliability of the scale administered for the confirmatory test at this phase of the study reveals acceptable indices (McDonald’s ω=.76; Cronbach’s α=.77). The factorial solution at this stage reveals that the single factor is maintained (χ²(df)=422(15), p<.001, KMO=.80) with factor loadings varying between .61 and .73. The share of variance explained is 46.60%.

| Figure 2. Measurement model testing the confirmatory structure of the infidelity risk scale |

2.1.2.3. Factorial Invariance or Measurement Equivalence Analyses

|

2.1.3. Discussion

- The present study contributes to the development of the literature on infidelity through the construction and validation of an instrument for measuring the risk of infidelity within couples. The results of exploratory and confirmatory factorial and invariance validations of this scale provided empirical data revealing that it presents a single factor structure, with excellent psychometric properties meeting the required standards. Systematic suitability assessment procedures have been determined by significant satisfactory thresholds (Boateng et al., 2018; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kaiser, 1974; Nunnally, 1978; Raykov, 2011). The invariance test of this scale revealed conclusive metric information respecting the standards defined by the psychometric literature (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Kline, 2016). Thus, evidence of the equivalence of the factor structures of the risk of infidelity scale has been established (Byrne, 1989; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2004; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). In view of these results, we conclude that the risk of infidelity scale can be used by researchers who are interested in this construct. It modestly addresses the shortcomings of Dallaire’s (n.d.) test of the risk of being unfaithful or deceived and makes it possible to predict, among individuals, the propensity to develop an extradyadic relationship.

2.2. Study 2

- The present study proposes an explanation of the risk of romantic infidelity based on sexual dissatisfaction in men and women. It defends the idea that men’s tendency towards extramarital affairs or extradyadic relations is not linked to their sexual dissatisfaction as is the case for women (Petersen, 1983). In this logic, women’s sexual dissatisfaction in marriage would be linked to the probability of being unfaithful and the probability of men to be unfaithful would have no relation to the quality of the sexual relationship in the relationship, but rather to the degree of love and affection felt towards the partner (Petersen, 1983). This study is therefore situated in the perspective of the thesis that the social logics which underlie extradyadic relationships and the dynamics of romantic pathways defined by clandestine relationships are specific to the gender (Garcia, 2016; 2018).

2.2.1. Hypotheses

- In addition to the elements cited above, the present study, which is carried out in an African context, is based on the idea that sexual non-exclusivity in couples can be a function of the cultural norms that individuals share and the representations that they have towards infidelity. In this sense, differences in moral perception of infidelity behavior are linked to cultural differences (Aldahadha & Al-Momani, 2023); which could induce varied logics in the conception of fidelity requirements in couples. In this vein, this research tests the hypotheses that: 1) in a traditional social context where the founding logics of couple relationships are based on a traditional family model carried by men, and where society constructs a framework, with a set of relationships without love or attachment (Brugère, 2020), the risk of infidelity observed in men is not linked to their sexual dissatisfaction (Petersen, 1983). It would rather reflect the absence of love and attachment, as well as the expression of their masculinity and a domination based on management constructed by the patriarchal system (Brugère, 2020); and 2) among women, on the other hand, the risk of infidelity is expected to be more associated with their sexual dissatisfaction. Clearly, the idea defended is that given that female sexuality is impacted by emotions, attachment and the feeling of love, unlike male sexuality, sexual dissatisfaction would further explain the risk of infidelity among women than among men.

2.2.2. Method

2.2.2.1. Participants

- The participants of this study are one hundred and seventy-four Cameroonians (N=174; 46 women and 128 men) involved in a romantic relationship. Their average age is 23.20 years (SD=4.07). They were met individually in the town of Dschang and agreed to participate voluntarily in the research. They were informed that the data they provided would be intended exclusively for research-related statistical processing purposes.

2.2.2.2. Measures and Procedure

- In addition to sociodemographic variables such as the age and sex of the participants, sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity were collected using two self-administered measures comprising items for which participants gave their opinion on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). (i) Measuring sexual dissatisfactionIt is an adaptation of the Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS; Hudson, 1982). All of its items were reformulated by introducing the negative form (is not) into the statements to assess sexual dissatisfaction, that is to say the opposite of the sexual satisfaction that this scale measures. The fourteen (14) items obtained therefore constitute a scale for measuring sexual dissatisfaction. Six (6) of them are reverse coded (e.g. “My sex life is exciting.”), while eight (8) are right-coded (e.g. “I find our sexuality disgusting.”) After the administration of this scale, the items were subjected to exploratory factor analysis. The results reveal a unifactorial structure consisting of 10 items with factor loadings >.40 and varying between .53 and 1.10. The exploratory factorial information is conclusive (KMO=.70; χ²(df)=251(28); p<.001) and the 10-item structure is reliable (α=.72; McDonald’s ω=.72). The measurement model validating the confirmatory structure of this scale adequately adjusts to the empirical data (χ²(df)=171(35); p<.001; CFI=.96; TLI=.93; SRMSE [95% CI] =.05[.00, .08]); RMSE=.05).(ii) Measuring the risk of infidelityThe scale used is the one that was validated in Study 1. For Study 2, its reliability information is satisfactory (Cronbach’s α=.77; McDonald’s ω=.77). Its confirmatory factor structure remains valid and adequately adjusts to the empirical data obtained from a sample of 147 individuals (χ²(df)=14.5(7); p<.05; CFI=.96; TLI=.95; SRMR=.04; RMSEA [95%CI]=.08[.01, .14]).

2.2.2.3. Data Analysis Procedure

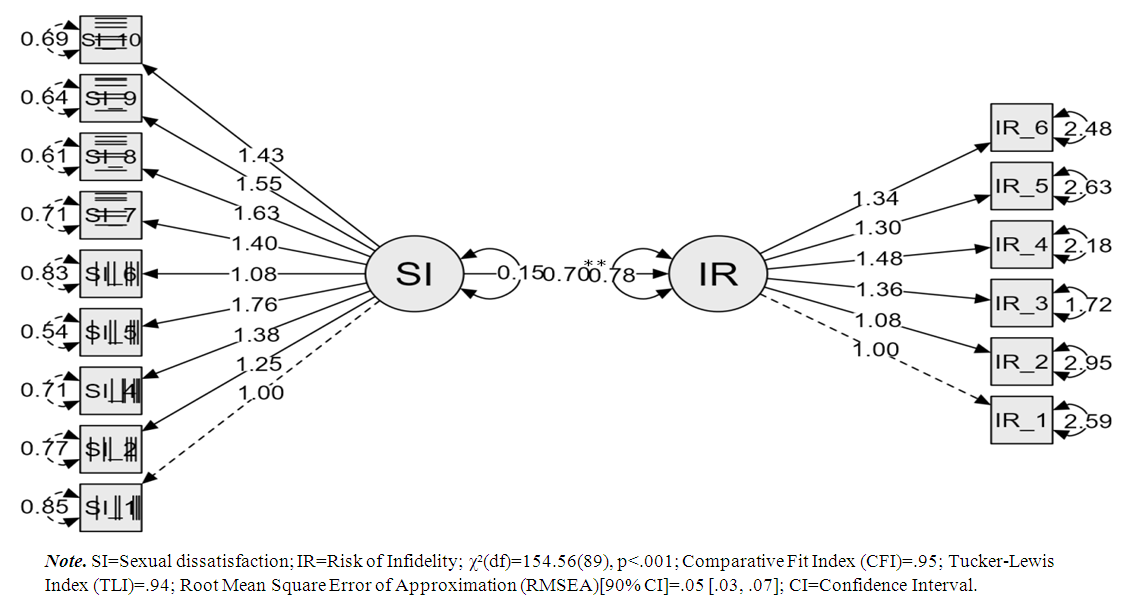

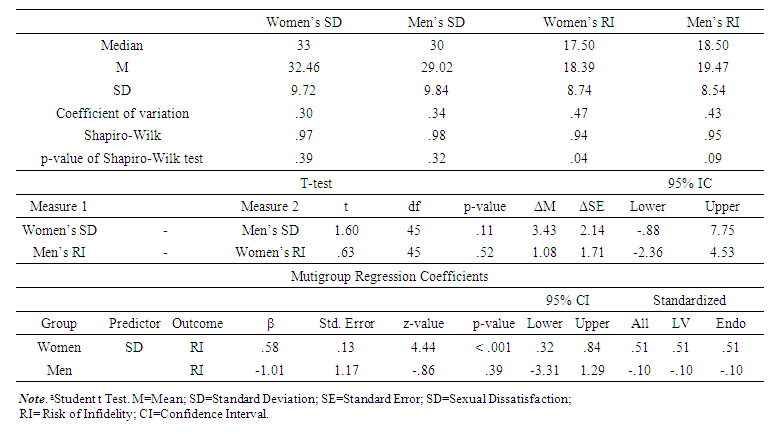

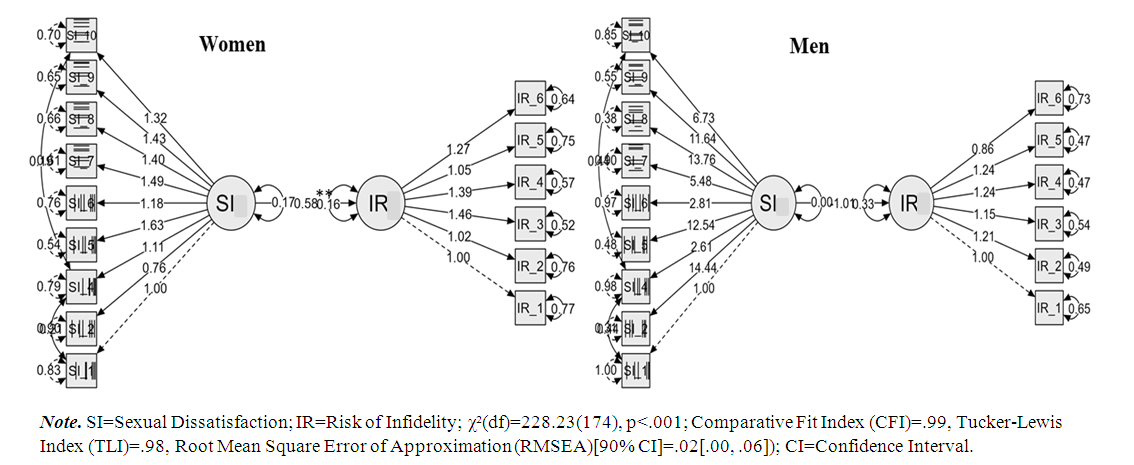

- The data were analyzed using JASP.17.1 software. Descriptive and correlational statistics were calculated (see Table 4). To establish a cause and effect relationship between sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity, an analysis of the structural relationship was carried out by performing Lavan’s syntax (See Figure 4). The standardized regression coefficient (β) as well as the adjustment parameters of the structural model were estimated (β, χ² (df), CFI, TLI, RMSEA). To compare the relationship between these two variables based on participants’ gender, a multigroup analysis was performed, with gender as the grouping (categorical) variable. The Lavan syntax executed for this purpose took into account manifest variables. Thus, two multigroup regression models linking sexual dissatisfaction to the risk of infidelity were performed. The estimated regression coefficients or factor loadings indicate the nature of the different relationships between these variables based on gender. A comparison test of means (T-test for a paired sample) relating to variables correlated according to gender was carried out in order to differentiate men from women in relation to the link between sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity.

2.2.3. Results

- The results presented in this section describe the variables of the study and test the links postulated in each hypothesis. They are in tables (see Tables 3 and 4) and a model (see Figure 3).

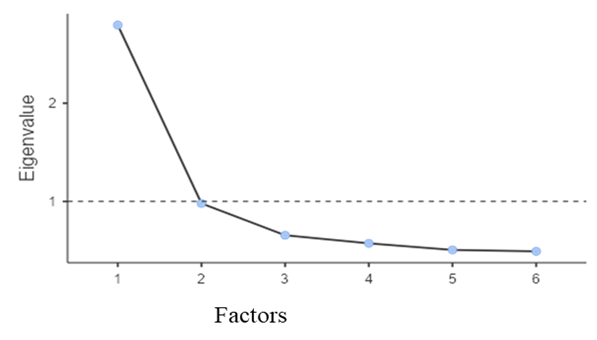

2.2.3.1. Preliminary Analyses

- Descriptive statistics show that participants have means relatively close to the median for sexual dissatisfaction (M=30; SD=9.81) and risk of infidelity (M=19.20; SD=8.07). There is a positive and significant relationship (p<.01) between sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity. Sex is significantly related to sexual dissatisfaction (p<.05) and not significantly related to the risk of infidelity (p>.05). The age of individuals is not significantly (p>.05) linked to either sexual dissatisfaction or the risk of infidelity (See Table 3).

|

2.2.3.2. Testing Research Hypotheses

- - Hypothesis 1

| Figure 3. Structural equation model explaining the relation between sexual dissatisfaction and risk of infidelity |

| Table 4. Comparative analysis of the link between sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity between gender |

| Figure 4. Multigroup structural equation model explaining the relation between sexual dissatisfaction and risk of infidelity depending on gender |

2.2.4. Discussion

- The present study aimed to test the link between the risk of infidelity based on sexual dissatisfaction depending on gender. The data collected provide empirical support for the hypotheses tested. Thus, sexual dissatisfaction significantly explains the risk of infidelity. Furthermore, gender is a factor to take into account in the analysis of the relationship between these two constructs. In this sense, the hypothesis that women are more sexually dissatisfied than men, and that this sexual dissatisfaction explains their risk of being unfaithful more than that of men is supported by empirical data (Garcia, 2018; Petersen, 1983). The extradyadic relationships observed in men would therefore be linked to factors other than sexual dissatisfaction, as suggested by Petersen’s (1983) propositions. Thus, the results of this study are in line with the social logics of extraconjugality and gender-specific marital pathways in a patriarchal context (Garcia, 2018).

3. General Discussion

- In this research comprising two studies, study 1 proposed a valid and reliable psychometric instrument from the point of view of standard exploratory, confirmatory and invariance tests of psychometric scales. The test of differential item functioning was found to be an indicator that the group of female participants performed almost similarly to their male counterparts. Thus, the latent structure of the items did not vary (Sideridis et al., 2015; Reise et al., 1993). This measure allows us to understand individual tendencies towards the risk of infidelity in men and women, consequently helping to facilitate the interest of future empirical studies for new perspectives of explaining risk of infidelity in couples and to anticipate on possible crises in sentimental and marital life. Study 2, for its part, observed that in the patriarchal context explored, the sexual dissatisfaction of partners induces the risk of infidelity. It also found that women are more sexually dissatisfied than men and the link between their sexual dissatisfaction and their tendency to engage in extradyadic or marital relationships is more marked than among men. It is for this reason that in a patriarchal system we explain male infidelity to certain factors such as the absence of love, attachment or the desire for expression and affirmation of masculinity (Brugère, 2020). In view of the above, the contribution of this study is twofold. Methodologically, it provides the literature with a viable tool for measuring the risk of infidelity; which is likely to boost the interest of the scientific community in empirical research for this construct which, until now, has not been the subject of abundant documentation. On a theoretical level, by focusing specifically on gender differences in the link between sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity within an African patriarchal society, this research reports that if sexual dissatisfaction explains the risk of infidelity among women, this is not the case for men. These two contrary trends are explained in particular by the fact that among men, infidelity is mainly linked to factors such as the absence of love, attachment or the desire for expression and affirmation of masculinity (Brugère, 2020). Indeed, in the particular case of traditional patriarchal societies, due to the fact that the man is the partner who holds the power within the couple, his acts of infidelity are tolerated or accepted, while those of the woman are condemned and considered a transgression of couple norms. In this type of society where masculinity and masculine traits are valued more than femininity and feminine traits (Brugère, 2020), men’s infidelity can be placed in the category of traits characteristic of masculinity. In this sense, the tolerance of male infidelity and the intolerance of female infidelity can be included in the psychological approach of patriarchy (Brugère, 2020); recognizing the fact that man’s infidelity is justified by the fact that masculine norms and values dominate double lives (Garcia, 2016, 2018).

4. Limitations and Perspectives

- Although this study makes a methodological and theoretical contribution to the field of research on the risk of infidelity, it has some limitations. One of these limitations is that it did not test strict (residual) and structural invariance. Future research may focus on verifying these parameters. It also did not connect the validated scale to the other scales relating to the construct of infidelity. In that perspective, the links between the risk of infidelity and attitudes towards acts of infidelity and forms of infidelity should be studied in future research. Other factors likely to modulate the link between sexual dissatisfaction and the risk of infidelity deserve to be analyzed alongside respondents’ demographic data. Cultural aspects, cultural representations of infidelity, adherence to Stockholm syndrome and sexual experiences or domestic violence can also be taken into account in explaining the risk of infidelity. Likewise, the present study did not relate the multidimensional scale of Aldahadha and Al-Momani (2023) relating to the reasons for infidelity with the scale of the risk of infidelity. However, the reasons underlying an act can also explain the intention to commit this act. Future research could address these limitations.

5. Implications of the Study

- The results of this study strengthen the diagnostic process of problems linked to infidelity in the couple. In this vein, the practical implications of these results could lie in the therapeutic perspective of Dallaire’s (n.d.) work on infidelity. Thus, as part of couples’s therapy, marriage or marital and family counselors can administer the infidelity risk measurement as a diagnostic or detection tool for the susceptibility of infidelity in marital relationships in order to anticipate on possible acts of infidelity. This would help couples in difficulty in their emotional and marital life. Likewise, in social centers, this psychometric scale can be used as an individual or couple consultation tool, in particular by emphasizing the catalytic role of sexual dissatisfaction on the risk of infidelity, to help couples in relational difficulties by making them aware of the causes and consequences of extramarital relations.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML