-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2023; 13(2): 29-37

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20231302.01

Received: Dec. 1, 2023; Accepted: Dec. 23, 2023; Published: Dec. 26, 2023

The Denial of Homosexual Identity as a Mediator of the Link between Beliefs in a Gay Conspiracy and Hostile Intentions towards LGBTQ People in a Highly Heteronormative Context: The Case of Cameroon

Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo

University of Maroua, Maroua, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo, University of Maroua, Maroua, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The literature reports that conspiracy beliefs are catalysts for hostility towards target groups. However, until now, the link between these two constructs has not yet been explored in the context of hostility against LGBTQ minorities, who are the object of persecution in many societies, one of which common characteristics is their heteronormative moral and legal inclination. To fill this gap, the present study examines, in the highly heteronormative Cameroonian context, the predictive potential of beliefs in gay conspiracy theories on hostile intentions towards LGBTQ minorities, through the mediation of the denial of homosexual identity. The research consisted of administering to 363 heterosexual participants (223 women and 140 men; average age: 25.87 years) measures relating to beliefs in a gay conspiracy theory, denial of homosexual identity, identification with the heterosexual group and hostile intentions towards LGBTQ people. The results provide empirical support for the prediction made. They allow the present research to contribute to the extension of the literature on the theoretical link between conspiracy beliefs and hostility towards target groups, by revealing that this link is relevant in the context of understanding hostility towards members of the LGBTQ community, in particular by taking into account the mediation of the denial of homosexual identity.

Keywords: Belief in the gay conspiracy, Denial of homosexual identity, Hostile intentions towards LGBTQ people, Heteronormativity, Homonegativity

Cite this paper: Achille Vicky Dzuetso Mouafo, The Denial of Homosexual Identity as a Mediator of the Link between Beliefs in a Gay Conspiracy and Hostile Intentions towards LGBTQ People in a Highly Heteronormative Context: The Case of Cameroon, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 2, 2023, pp. 29-37. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20231302.01.

1. Introduction

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer people, grouped under the acronym LGBTQ, are classified in the category of sexual minorities (Worthen, 2013). This position regularly exposes them to the harsh experience of hostility from heterosexual people (Herek, 2007), particularly due to the fact that their sexual practices are far from the standards valued and promoted by the majority of the population (Falomir-Pichastor & Mugny, 2009; Gulevich et al., 2018) for which sexual activity is practiced between people of different biological sexes exclusively (heteronormativity; Herek, 1994). As a result, LGBTQ people are considered a threat (Tjipto et al., 2019) to these heteronormative societies; hence the rejection they are subject to. This rejection characterizes the denial of identity which can materialize through ignorance, stigmatization and discrimination of these people (Thöni et al., 2022). Its major consequence is that it leads to a deterioration in the mental health of LGBTQ people by increasing the risk of depression and anxiety, since it constitutes a stressful situation that is difficult to manage (Pressman et al., 2013; Thöni et al., 2022).The difficulties that LGBTQ people face in societies categorized as heteronormative result in particular from the threat they represent (Tjipto et al., 2019). This threat is likely to induce beliefs in conspiracy theories against them, since the literature establishes links between feelings of threat and conspiracy beliefs (van Prooijen & van Dijk, 2014; van Prooijen & van Lange, 2014). Conspiracy theories constitute attempts to explain important political and social events and/or circumstances, through a focus on conspiracies fomented by powerful actors (Douglas et al., 2019; Jolley et al., 2022). More specifically, they argue that there is a small group of powerful individuals who manipulate events to achieve generally illicit and malicious goals. With regard specifically to conspiracy theories targeting LGBTQ people, they are structured around the idea that there is a “gay lobby”, whose aim is to propagate homosexuality, through the indoctrination of minors, the questioning of the natural/moral order and the promotion of a totalitarian ideology based on gender theory (Salvati et al., 2023). These beliefs impact individuals’ behavior towards the LGBTQ community, targeted because its ideology and way of life undermine traditional religious values or endanger natural sexual differences (Tjipto et al., 2019). Indeed, it appears from the literature on conspiracy theories that beliefs in the existence of a conspiracy are likely to lead to the rejection of all conspirators (Jolley et al., 2022; Landrun & Olshansky, 2019).Despite the fact that the literature on belief in conspiracy theories is growing, conspiracy theories related to LGBTQ people are very little studied (see Salvati et al., 2023 for a very recent exception); which is likely to prevent not only the understanding of these theories, but also the analysis of their potential consequences on the relationships between the people who adhere to them (heterosexuals) and those who are their targets (LGBTQ people). The consequence is that given that conspiracy research findings cannot be generalized to LGBTQ-specific issues without caution, it is necessary to specifically address conspiracy beliefs against the LGBTQ community to understand the mechanisms by which they are linked to hostile intentions towards this community. The present study is situated in this perspective. It examines the link between conspiracy beliefs relating to LGBTQ people and hostile intentions towards them via denial of their sexual orientation; a variable with the potential to catalyze the adoption of various homonegative behaviors (Diamond et al., 2017; Morgenroth et al., 2021). It is conducted in the Cameroonian societal context, which can be considered highly heteronormative, taking into account not only the criminal conviction of homosexuality and sodomy, but also the numerous abuses committed against LGBTQ people in this country (Amnesty International, 2013; Human Rights Watch, 2021).Heteronormativity and beliefs in the existence of a gay conspiracyIn many societies around the world, LGBTQ people are victims of torture, hate crimes and ill-treatment, including attacks on their dignity, physical attacks and even murder (Amnesty International, 2013; Human Rights Watch, 2021). The source of these homonegative attitudes and behaviors is found in gender norms, which predominate in the majority of heteronormative societies (Gulevich et al., 2018). Indeed, heteronormativity defends the idea that there are two stable and well-defined gender categories, hence the fact that sexuality between two people of different sexes (a man and a woman therefore) is the norm (Closon & Aguirre-Sánchez-Beato, 2018; Herek, 1994, 2007). Thus, in heteronormative societies, predominant gender roles motivate individuals to expect men to be independent, robust, assertive, self-confident and anti-feminine, while women are expected to be emotional, warm, sensitive, fragile and concerned about others (Bourguignon et al., 2018). These roles motivate the expectation that individuals will be sexually attracted to a person of the opposite sex (Herek, 1994; 2007). Heteronormativity involves specific norms, values and beliefs that construct gender identity and participate in the formal differentiation between men and women (Bem, 1981; Bourguignon et al., 2018); hence the subsequent hostility towards people whose behavior does not conform to these standards (Bourguignon et al., 2018; Marquez et al., 1998), like attacks against LGBTQ people, whose practices transgress the traditional vision of gender identity (Konopka et al., 2020; Piumatti, 2017). Due to these transgressions, these people are considered a threat to heterosexuals (Tjipto et al., 2019); a threat that could incline them to develop thoughts of a conspiratorial nature around homosexuality, if we place it in the perspective of the theoretical link between feelings of threat and conspiratorial beliefs established by the specialized literature (van Prooijen & van Lange, 2014).Conspiracy thinking is the attempt to explain the ultimate causes of events or important political and social circumstances by highlighting plots secretly prepared by two or more powerful actors (Douglas et al., 2019; Jolley et al., 2022). This definition highlights three essential elements that characterize conspiracy theories: 1) the actions and objectives pursued are illegal, harmful and threatening; 2) the conspirators succeed in their plan because they are particularly powerful, manipulative, devious and can control the course of events; and 3) conspirators operate in secret and use cover-ups to hide their true intentions from the public (van der Linden, 2015). Conspiracy theories then predict suspicious intergroup perceptions involving the coalitionary action of an outgroup perceived as hostile (a government, a secret agency or a minority group for example) and whose goal is to harm an ingroup (ordinary citizens for example) with which individuals identify (van Prooijen & Song, 2021). They therefore offer the possibility of making sense of the situations that individuals face.People believe in conspiracy theories when they face situations that tend to impact their lives, and place them in distressing psychological conditions involving feelings of helplessness, lack of control and uncertainty (Leman, 2007; van Prooijen, 2017; van Prooijen & Jostmann, 2013). Research reports that individuals who believe in conspiracy theories have high levels of psychological stress and cynicism, and low self-esteem (Cookson et al., 2021; Imhoff & Lamberty, 2017). Additionally, experiences of anxiety and depression may increase one’s inclination to believe in conspiracies (Douglas et al., 2017; Liekefett et al., 2021; Swami et al., 2016). These conditions then predispose them to have hostile social reactions towards individuals and groups considered to be the conspirators (Jolley et al., 2022). In the specific case of homosexuality, these reactions are the consequence of essential socio-psychological mechanisms which lead people to perceive the threat linked to this sexual orientation and to share ideas that we would qualify as conspiratorial, such as for example on the socio-economic status of LGBTQ people who are considered rich and well-off (Bettinsoli et al., 2022), or on their alleged associations located in the high political-administrative sphere of a country like Cameroon (Menguele Menyengue, 2014, 2016; Messanga & Sonfack, 2017; Pigeaud, 2011).When people believe that sexual orientation is innate (gender is determined by biological factors and assigned at birth), this belief prevents them from buying into the idea that homosexuality or gay power can take scale in society. On the other hand, if they believe that sexual orientation is the consequence of psychosocial factors, as in the case where they adhere to the idea that gay propaganda implements techniques to transform heterosexuals into homosexuals (see Machikou, 2009; Tjipto et al., 2019), then they may believe that homosexuality and the relative power of homosexuals can grow and, therefore, constitute a threat to heterosexual identity (Gulevich et al., 2018). Indeed, proponents of gay conspiracy theories rely in particular on traditional gender values; hence the fact that Salvati et al. (2023) constructed a two-dimensional psychometric method, called the GILC Scale (Gender Ideology and LGBTQ+ Lobby conspiracies), including both a measure for belief in the conspiracy of a LGBTQ+ lobby and a measure relating to attitude towards gender ideology. Traditional gender values are opposed to gender ideology, due to the fact that for them, there are two biologically shaped genders; the idea of bio psychosocial or personal choice gender being unacceptable. From this perspective, gender identity is not malleable (Gulevich et al., 2018); a thesis fiercely defended by people who adhere to religious teachings (Marchlewska et al., 2019). In general, people who believe in LGBTQ+ lobby conspiracy theories (see Salvati et al., 2023) think, as do those who believe in gender conspiracy theories (see Marchlewska et al., 2019), that gender studies and gender ideology are components of a secret conspiracy of influential people (an elite; Salvati et al., 2023) whose role is to weaken heterosexuals. Gender studies and gender movements, specifically, would be a cover under which feminists and LGBTQ people camouflage themselves to deliberately and covertly reject the traditional differentiation between men and women; a malicious maneuver whose aim would be the destruction of the family unit, considered by Catholic believers, for example, as a sacred institution. This is why these people have high threat sensitivity and demonstrate both social distance and hostility towards LGBTQ people (see Marchlewska et al., 2019). In Cameroon, a country located in the Sub-Saharan region of Africa, homophobia is institutionalized, notably in the Penal Code, article 347-1 of which stipulates that: “Is punishable by imprisonment of six (06) months to five (05) years and a fine of twenty thousand (20,000)1 to two hundred thousand (200,000)2 Francs, any person who has sexual relations with a person of his sex.” This legal provision offers protection to the population by implicitly legitimizing abuses against members of the LGBTQ community, including humiliation, ambushes, public insults, arbitrary arrests, beatings, torture, and even assassinations (Amnesty International, 2013; Human Rights Watch, 2021). In addition to this implicit legal protection, hostility towards LGBTQ people in the Cameroonian context is linked to beliefs shared about them in popular imagery (Messanga et al., 2008; Messanga & Sonfack, 2017). Indeed, they are portrayed as cult followers or sorcerers; hence the fact that their sexual orientation is considered a dishonor, a curse, a sin and a mental imbalance (Lado, 2011). Furthermore, public opinion shares the idea that homosexuality in particular is a practice which is close to prostitution, since it is constantly maintained between the powerful, sitting in the highest administrative, political and economic spheres (Pigeaud, 2011), and the underprivileged, in desperate search of social advancement or promotion (Gueboguo Senguele, 2006). From this perspective, homosexual practices would then constitute transactional sexuality, encouraging clientelism (Menguele Menyengue, 2016). They would not be the consequence of a simple attraction towards a person of the same sex, since their aim would be the acquisition of power or a position in the politico-administrative apparatus (Messanga & Sonfack, 2017). Indeed, in popular Cameroonian imagery, sodomy involved in male homosexual practices would materialize the act by which the active homosexual would submit the passive homosexual; this submission being situated in the perspective of the dictatorship of sodomy for promotion, to which the neologism “homocracy” refers (Menguele Menyengue, 2016). This means that in the Cameroonian context, LGBTQ people in general and homosexuals in particular are not considered individuals whose partner choices arise from a natural attraction towards a particular category of people (Messanga & Sonfack, 2017). Their perception as individuals who engage in homosexual practices solely from a ritual or magico-religious perspective to acquire power or money, therefore denies them homosexual identity. The denial of homosexual identity and its negative effects on LGBTQ peopleThe term denial of homosexual identity refers to the rejection or non-recognition of the LGBTQ people’ sexual orientation (Thöni et al., 2022). It is accentuated when heterosexual people perceive an incompatibility between themselves and members of the LGBTQ minority. This incompatibility is based on the social identification mechanism, supported by social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). For this theory, people’s social identity is constructed when they perceive themselves as members of one of the existing categories in society. This will incline them to feel positive emotions for the members of their category and negative emotions for the members of other categories (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987). The recognition of the identity of a group is perceived through three important mechanisms (Honneth, 1996): 1) love, which reflects the fact that to be recognized is to have the possibility of building emotional links with the members of the group; 2) respect, which implies that to be recognized is to have one’s rights respected and to be perceived as a full member of the group; and 3) singularity, which suggests that to be recognized is to be accepted and valued in one’s particularity. Failure to take these elements into account implies the denial of a person’s social identity (Da Silva et al., 2021; Honneth, 1996); a phenomenon that LGBTQ people constantly face in heteronormative contexts particularly, since their sexual orientation is considered to be both illegitimate and inconceivable (Maimon et al., 2019; Thöni et al., 2022). The denial of homosexual identity is a catalyst for various negative behaviors towards LGBTQ people; and these behaviors are accentuated by the negative affects felt towards them. Concretely, research reports that stigma, prejudice and discrimination against LGBTQ minorities result from denial and negative affects towards their members (Diamond et al., 2017; Morgenroth et al., 2021). These affects are, among others, fear, distrust and disgust (Herek, 1994; 2007), which predispose to stigmatize, discriminate and have hostile intentions against LGBTQ people (Maimon et al., 2019). Due to this hostility, these people are exposed to psychological (anxiety and depression for example) and relational problems (distancing and difficulties with social integration in particular) (Thöni et al., 2022).The present research: Beliefs in a gay conspiracy, denial of homosexual identity and hostile intentions towards LGBTQ peoplePrevious research on conspiracy beliefs reports that these attempts to explain social events and situations are likely to incline individuals and groups who consider themselves victims of the conspiracy to adopt hostile attitudes and behaviors towards people and groups considered to be the main instigators of the conspiracy (Jolley et al., 2022; Imhoff et al., 2022; van Prooijen et al., 2022). However, due to the fact that conspiracy theories relating to the existence of a LGBTQ lobby, whose alleged role is to implement a gay agenda, are an almost non-existent area in the conspiracy literature (Salvati et al., 2023), little is known about the potential links between conspiracy beliefs and hostile attitudes and behaviors towards members of the LGBTQ minority. It is this unanswered concern that this research addresses. It aims precisely to extend the theoretical link established between conspiratorial beliefs and intergroup hostility, in the area of the treatment inflicted on LGBTQ people, particularly in highly heteronormative societies where these people’s security and social situation are worrying, due to the daily abuses which they are the targets (see Martìnez-Guzmán & Íñiguez-Rueda, 2017; Moleiro et al., 2021; Tillewein et al., 2023). Drawing on the potential link between conspiracy beliefs and denial of homosexual identity suggested by the perception of the LGBTQ people’s sexual orientation in the Cameroonian context (Messanga & Sonfack, 2017), and the theoretical link between denial of homosexual identity and homonegative attitudes and behaviors (Diamond et al., 2017; Morgenroth et al., 2021), this research concretely aims to test the idea that the denial of homosexual orientation mediates the relationship between beliefs in a gay conspiracy and hostile intentions towards LGBTQ people.

2. Method

- ParticipantsThis study was carried out in the Cameroonian context with a sample of 363 heterosexuals (140 men and 223 women). Their ages range from 18 to 60 years (M= 25.87, SD= 9.005). To ensure the ethics of the research, consent from participants was obtained before administering the questionnaire. They were also assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses.Material and procedureParticipants were administered a series of measures including items for which they were asked to give their opinion on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree):- beliefs in a gay conspiracy theory (α= .74) were measured with a 4-item scale adapted from the Generic Scale of Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories (Brotherton et al., 2013). A sample item suggests that: “a small, secret group of people are responsible for all the major decisions that are made in the world, such as practicing homosexuality.” We would like to point out that the data collection was done before the publication of the Gender Ideology and LGBTQ+ Lobby Conspiracies (GILC) scale (Salvati et al., 2023); hence the fact that it was not used in the present study;- denial of homosexual identity (α= .77) was measured with a 5-item scale inspired by the literature (Thöni et al., 2022). One of these five items states that: “I do not feel able to recognize homosexuals as full people in this country”;- the participants’ degree of identification with the heterosexual group (α= .92) was assessed using a 4-item scale adapted from Becker and Wagner (2009). One item proposes: “Being heterosexual is very important to me”;- hostile intentions towards LGBTQ people (α= .75) were measured using a 6-item scale adapted from Schaafsma and Kipling (2012). For example, one item states: “I would like to hurt homosexuals.”

3. Results

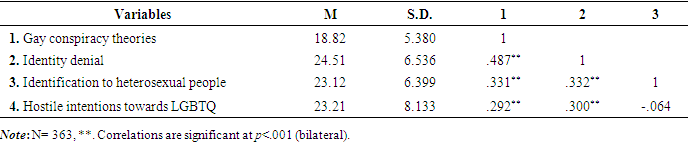

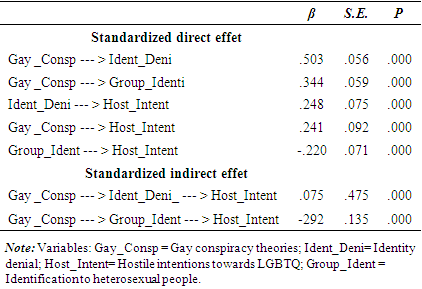

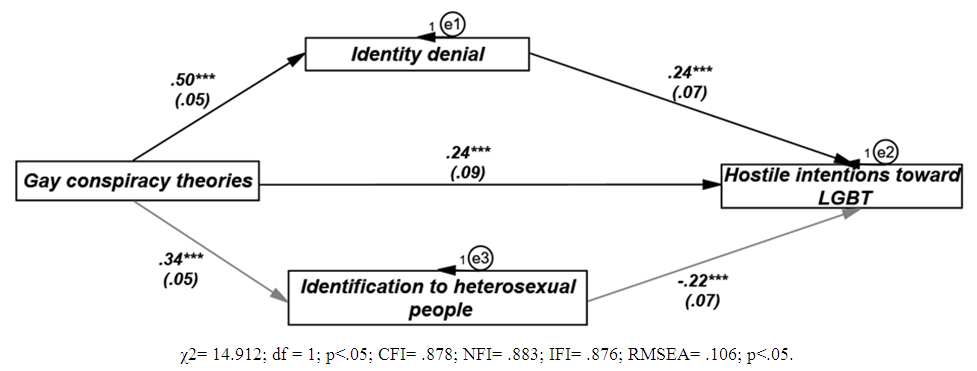

- The results of this study are presented in two stages. First of all, we are interested in the means, standard deviations and inter-correlations between the variables (see Table 1). Then, the weight of the effects between the variables is tested (see Table 2), based on a path model (see Figure 1) analyzed with the SPSS Amos version 23 software.

|

| Figure 1. Structural equation model of the prediction between variables of the study |

|

4. Discussion

- The present research was conducted to examine the mediating effect of denial of homosexual identity on the relationship between belief in the existence of a gay conspiracy and hostile intentions towards LGBT people in the Cameroonian societal context. This context can be considered highly heteronormative due not only to legislation condemning, at the criminal level, the offenses of homosexuality and sodomy, but also to the violence based on sexual orientation which has been recorded there for many years (Amnesty International, 2013; Human Rights Watch, 2021). The data collected after administering various measurement instruments to participants provide empirical support for the hypothesis tested, revealing participants’ strong inclination to develop hostile intentions towards LGBTQ minorities due to their belief in the existence of a gay conspiracy, via their denial of homosexual orientation and not their identification with the heterosexual group. The results of this research support the theoretical models which defend the thesis that conspiracy beliefs are an important parameter in the explanation of intergroup conflicts (Jolley et al., 2022; van Prooijen, 2020; van Prooijen et al., 2022; van Prooijen & van Vugt, 2018). These beliefs are activated by threatening social situations that trigger epistemic processes leading to a search for meaning or an appropriate explanation for the said situations, as is the case with the threat posed by LGBTQ people’ lifestyle (Tjipto et al., 2019), particularly in heteronormative societies. These societies are strongly attached not only to the traditional vision of gender identity (Konopka et al., 2020; Piumatti, 2017) but also to the ideology of survival (Adamczyk & Pitt, 2009). Indeed, sense making processes give rise to conspiratorial beliefs, especially when a threatening and despised outgroup is made salient (van Prooijen & Song, 2021).In the field of research on conspiracy theories, work on the LGBTQ community is almost non-existent, with the notable exception of the very recent study by Salvati et al. (2023). In this context, the present study constitutes a contribution to the structuring of this unexplored area of the specialized literature. It reveals that the link between conspiracy beliefs and intergroup hostility is relevant to LGBTQ minorities; a relationship not yet established in the literature. In this research, this relationship is mediated by the manifest denial of homosexual identity, in a context where individuals do not believe that attraction to a person of the same sex is a natural fact, but that it is located more in the perspective of a transactional exchange between the powerful and the dispossessed with a view to acquiring power or a social position (Gueboguo Senguele, 2006; Menguele Menyengue, 2016; Messanga & Sonfack, 2017; Pigeaud, 2011). It is therefore easy for individuals to believe that LGBTQ people are secretly plotting against traditional gender values, in particular by seeking to convert heterosexuals into homosexuals (Machikou, 2009; Tjipto et al., 2019). Previous studies had not until now interested in this relationship.The data collected in this study also contribute to the extension of previous observations on the denial of homosexual identity (Maimon et al., 2019; Thöni et al., 2022) by revealing that it is linked to beliefs about the existence of a gay conspiracy; a fact not previously documented in the specialized literature. Two psychological processes supported by social identity theory help elucidate the relationship between belief in a gay conspiracy and the denial of homosexual identity reported in this research: 1) the perception of similarity with the ingroup; and 2) the perception of contrast with outgroups (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). The first leads heterosexuals to perceive themselves as similar to each other, implying a positive group identification; and the second leads them to the perception of the heterosexual group as dissimilar to LGBTQ people, then implying the perception of threat and the rise of negative emotions such as fear, hatred, and distrust towards them (Herek, 1994; 2007). These processes are accentuated when individuals strongly believe in intergroup conspiracy theories. This supports the literature which defends the idea that conspiracy beliefs incline individuals to accentuate love for the ingroup and hostility towards outgroups (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021; Marchlewska et al., 2019).

5. Conclusions

- The present research concluded that denial of homosexual identity mediates the relationship between belief in the existence of a gay conspiracy and hostility towards members of the LGBTQ community in the Cameroonian context; a context characterized by the strength of communities’ adherence to the norm of heteronormativity and the ideology of survival (Messanga & Sonfack, 2017). These observations contribute to documenting the literature relating to the effects of conspiracy beliefs in general and beliefs in the existence of a gay conspiracy in particular, which are much less documented in the scientific literature, although they flourish in the popular imagery, particularly in the American context (Friedersdorf, 2012), within conservative and religious circles. Indeed, apart from the work of Salvati et al. (2023), very little is done in the conspiracy literature to document belief in gay conspiracy theories specifically. However, as this research reports, the belief in the existence of a LGBTQ lobby whose mission would be to propagate LGBTQ ideology and convert heterosexuals into homosexuals (Machikou, 2009; Tjipto et al., 2019) is a phenomenon likely to explain the discrimination and violence suffered by LGBTQ people in various regions of the world, particularly those with a strong heteronormative inclination (see Martìnez-Guzmán & Íñiguez-Rueda, 2017; Moleiro et al., 2021; Tillewein et al., 2023). As suggested by Salvati et al. (2023), research should continue in this direction, not only to document conspiratorial beliefs relating to LGBTQ people, but also to understand the psychosocial mechanisms responsible for homonegative attitudes and behaviors that prevent many societies from being more inclusive, by fully integrating sexual minorities.

Notes

- 1. 32,33 USD2. 323,33 USD

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML