-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2023; 13(1): 14-23

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20231301.03

Received: Sep. 11, 2023; Accepted: Oct. 7, 2023; Published: Oct. 13, 2023

How COVID-19 Risk Factors influenced Performance Anxiety among Workers during the Outbreak of the Pandemic in Bamenda, Cameroon

Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb

Department of Counseling Psychology, FED, The University of Bamenda

Correspondence to: Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb, Department of Counseling Psychology, FED, The University of Bamenda.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

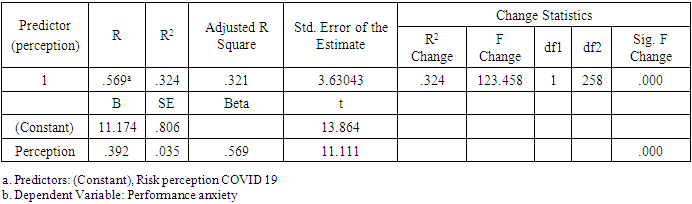

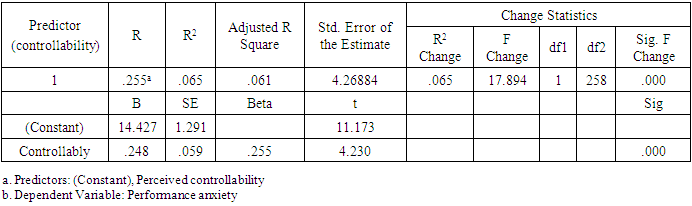

Debates on the outbreak of Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) had recognized individual and environmental factors as antecedents of health behavior outcomes. During the pandemic, workers at the frontline were often caught in between service delivery and risk factors, and activities appeared moderated by perceived risk of the health chaos. Although it had been argued that perceived risk of severity, susceptibility and control of the disease could promote preventive behaviors, the current study assumed that perceived threat fostered psychological distress among workers during their transactions. Using a sample of 260 workers (males 53.5%; females 46.5%) in Bamenda municipality, the study examined the extent to which performance anxiety among workers was predicted by perceived risk perception of the disease during their operations. An instrument (aggregate α = 0.853) was used for data gathering and regression analysis performed to estimate variations in the outcome measure. Perceived risk explained variations in performance anxiety (R2=.324, P<0.05) and perceived behavioral control was reported as a significant predictor of performance anxiety (R2=.065, P<0.05). Using the Health Belief Model as an explanatory framework, a number of potential practical strategies were advanced to enable workers reconstruct their beliefs and build the necessary psychological resources to cope with performance anxiety. Discussion was focused on current measures advanced in preventing the disease and in alleviating psychological distress among persons at work in different sectors of the economy.

Keywords: COVID-19, Risk perception, Perceived controllability, Performance anxiety, Workers

Cite this paper: Fomba Emmanuel Mbebeb, How COVID-19 Risk Factors influenced Performance Anxiety among Workers during the Outbreak of the Pandemic in Bamenda, Cameroon, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2023, pp. 14-23. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20231301.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Towards the end of 2019, an outbreak of a deadly disease in China known as the novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) spread rapidly to other countries worldwide with dire consequences on human, social and economic activities. As a public health disaster loaded with risk factors, efforts to contain the spread of the virus across the world were perceived as unprecedented (Toan, 2020). In addition to public health effects, the disease caused a major economic shock (Bartik, Bertrand, Cullen, Glaeser, Luca, and Stanton, 2020; Qiu, Chen and Shi, 2020), justifying emerging interest in effects on entrepreneurs, workers, business resources and recovery strategies. Although responding to the exigencies of the pandemic often led to preventive thoughts and patterns, it was observed that it could trigger a dark experience since responses often occured in the form of strain symptoms. As a human-to-human transmissible disease, corona virus was noted as the largest outbreak of atypical pneumonia since the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 (Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho, Ho, 2020). Apart from person-to-person, disease spread was possible through contact with contaminated surfaces and this heightened perceived risk associated with business interactions with colleagues, clients, goods and services. Perceived risk refered to beliefs about the disease, which are enduring individual characteristics that shape behavior and can be acquired through socialization (Abraham and Sheeran, 2014). This in anyway did not exclude the mediated role of individual factors in the course of business socialization and health behaviors. Transmission of the virus was fast, and controversies about cure and vaccine posed a serious threat and increase level of uncertainty experienced by the public, Governments and health agencies. Since vaccines or treatments have not yet been developed, avoiding exposure was considered the most appropriate strategy to prevent infection from the virus (Shabu, Amen, Mahmood and Shabila, 2020). This required innovative patterns of thinking and behaviors that were no doubt restricted, and often at variance with basic norms of economic interactions. Anyway, COVID-19 had pushed businesses across the world to rapidly operate in newer and more resilient ways as enterprises change their priorities in response to old challenges (Vermaa and Gustafsson, 2020). Nevertheless, responding to the demands of this complex situation could lead to anxiety due to extant demands by competing environmental and threatening stressors that were equally indispensable to survival and sustainable livelihood. Although the virus had created economic and social consequences affecting employees with regards to low wages, loss of income and jobs expressing more interest in economic effects (Vermaa and Gustafsson, 2020), the present study assessed the health impact of workers and service provides within the context of the pandemic. Linking service provision, risk and anxiety of workers was critical in business context with the arrival of the corona virus disease. Cheng & McCarthy (2018) noted that while responding to the pandemic in the midst of economic activities, anxiety interfered with the personal lives of workers and their performances due to feelings of nervousness, uneasiness, and tension about job-related performance. Furthermore, it was probable that performance anxiety in the context of health crisis played a pivotal role with respect to immediate and long terms benefits with respect to well-being and business performance of workers. Considering that susceptibility and sensitivity to anxiety were attributed to workers’ cognitive features such as perceptions and psychological preparedness (Papageorgi et al., 2007), understanding the link between COVID-19 risk perceptions as a factor in performance anxiety was critical to the health of workers. With regards to analytical framework, the Health Belief Model (HBM) had often been used to explore the predictive utility of perceived risk and health outcome of individuals (Abraham and Sheeran, 2014). This justified the use of the model in the study to explain the relationship between risk perception and performance anxiety of workers in the face of the pandemic. Human perception and behavioral responses to the risk of epidemics had become a crucial factor to studies during the spread of corona virus (Shabu et al., 2020). The expressed a dire need to understand and assess how it affects health outcome behaviors of economic actors and their operations. Since risk determined emotions and behaviors towards risk factors in a particular direction, the closeness of risk to perception appeared justifiable. Previous studies had revealed a profound and wide range of psychosocial impacts on people at the individual, community, and international levels during outbreaks of infections (Pan et al., 2020). This was pertinent with growing uncertainty surrounding the outbreak of the pandemic, which is of unparalleled magnitude as compared to previous diseases. Following the outbreak, people in different activities that were naturally driven by social interactions were at high-risk of the disease. This was the case with actors in economic activities where patterns of interaction necessary in delivering goods and services became a potential source of disease spread and worry generating mix feelings. This concurred with the assertion of Bodrud-Doza, Shammi, Bahlman, Islam and Rahman (2020) that the spread of COVID-19, partial lockdown, disease intensity, weak governance in the healthcare system, insufficient medical facilities, unawareness, and misinformation bred fear and anxiety in people. This could not exclude those at the centre of economic activities who had to serve the public to survive, grow and sustain the economy. Therefore, Shabu et al., (2020) suggested that understanding how people perceive the risk of the virus and its impact on undertaking protective behavior could guide public health policymakers in taking the required measures to limit the spread. Emerging debates on COVID-19 pandemic recognized its rapid spread and burden on health and economy of the general public. Popular opinion held that the virus had the potential to affect mental health of healthcare workers who stood at the front line of this crisis (Bults et al., 2011; Shabu et al., 2020; Sofia at al., 2020). It was noted that that frontline actors in varied categories as workers and business persons rendering basic services to the wider population were likely to face the odds of the virus. Furthermore, the pandemic had caused massive dislocation among small businesses due to lockdowns and closures with disruptions in business activities (Bartik et al., 2020). For instance, closure of educational institutes due to the pandemic did not only affect students and teachers but also created economic and social consequences related to digital learning, internet facilities, childcare, food insecurity and healthcare (Vermaa and Gustafsson, 2020). Occupational groups were also considered at high risks since they interacted with both carriers and super carriers, and require the necessary attention. Most severe cases and deaths had occurred in adults above 50 years of age with implications on the workforce since employees and economic operators were at high risk of the pandemic. With person-to-person mode of spread, workers were exposed and may experience performance anxiety due to perceived loss of interacting and subsequent economic losses in the context of the pandemic. Apart from health effects, the pandemic appeared to have hit hard on workers and business persons due to effects on daily wages, loss of jobs, their sources of income due to fear of business dealings (ILO, 2020), and this might have raised the level of psychological distress experienced by frontline workers. In as much as perceived severity and susceptibility to the disease could promote preventive motivation, it was likely that they could trigger anxiety, depression and stress symptoms in frontline actors in the process of business interactions. Despite the economic concerns, responses to the crisis had been humanitarian-oriented with measures such as lockdowns and social distancing, which were not in any way friendly to work and business transactions. Therefore, individuals were expected to navigate choices involving weighing risk for consequences with benefits of action (Ferrer and Klein, 2015). This was consistent with the manifestations of the pandemic due to perceived severity and deadly nature of the disease in work circles, not excluding potential challenges in the control of the pandemic through behavioral adjustments. Despite the potential risk of the disease in business operations, there were at the time no known information on risk perception and performance anxiety particularly with workers in Cameroon. Considering that studies on pandemics should have addressed critical emotional dimensions such as anxiety, uncertainty and embarrassment that played a role in decision making (Bults et al., 2011), it was essential for studies in-context to address the relationship between risk perception and anxiety experienced by workers during operations. Furthermore, interest in people in occupations could be justified by the recognition that they require optimal psychological functioning to operate their activities, while simultaneously being subjected to psychological and physical distress. Due to perceived severity and susceptibility of the virus, the Health Belief Model (HBM) was used to explain relationships in the study considering that it had the advantage of specifying a discrete set of common-sense beliefs that appeared to explain the effects of predictive utilities on health behavior (Abraham and Sheeran, 2014; Costa, 2020), which were anyway, susceptible to change through a variety of educational and counseling interventions. Shiina et al. (2020) noted that the estimation of the potential risk-proportion in the community, and understanding their cognitive and behavioral characteristics may help in developing epidemic control strategies, and this could be useful in managing the spread of the virus in local contexts.

1.1. Workers at the Frontline

- The corona virus pandemic the world over affected Cameroon and the spread of the disease became a disturbing affair in health and political circles. There were stringent measures put in place by the Government and further reinforced the resources of local health and administrative authorities. Measures taken to mitigate the spread included but not limited to health screening at certain points of entry, social isolation, institutional and home quarantine, social distancing and community containment measures. Such strategies were designed to deal with testing, quarantine and treatment facilities in order to contain the spread and treat the infected. Although the quick and stringent measures observed at the outbreak of the disease including awareness raising, education and suspension of activities in some sectors gave hopes to the population, there was still great fear concerning the management of the pandemic. The first positive case of corona virus was confirmed in Bamenda on 20th April, 2020 amidst tension and uncertainty. The arrival of the pandemic, exposure at occupational sites, thought of taking virus to family, ambiguity with regards to access and use of protective devices, protection of children and access to medical care if infected could increase perceived risk of the disease. Although health behavior outcome could be preventive, it could equally generate unpleasant feelings in both employees and self-employed workers. Crowded areas involved a greater risk for droplet-transmitted virus and individuals living in urban areas were expected to be more affected (Özdin and Özdin, 2020). This was the case with Bamenda, where workers were likely to interact more with people at risk of the virus due to high density and intense business activities. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the virus and related concerns only came to add to the long term psychological injuries and pain already inflicted by ongoing Anglophone crisis in the area. In the face of COVID-19 pandemic, behavioral responses were perceived as important factors moderating the spread of the virus through measures put in place by the Cameroon Governement, reinforcing those of the World Health Organization (WHO). But compliance with preventive measures such as social distancing, wearing of face masks, hand sanitizing and reduced public interactions could have been dependent on the personality, willingness and ability of people to adhere to these prescriptions. In this vein, the relationship between perceived risks and behavioral responses might had been considered when one examined the uptake of available information on deadly pandemic (Kaulu et al., 2020), and this could equally account for the perception and control of the pandemic with regards to health outcome in the municipality. Therefore, responses to the pandemic could depend on risk perception in-context. It had been argued that while perceptions could attract positive responses, meaning given to the pandemic could also attract negative experiences such as fear, tension, and uncertainty. Apart from micro business operators, office workers who dared to execute their assignments were subjected to the same risks since they had to interact with people and essential business properties in the risk environment. If for instance, healthcare workers who have treated patients and become infected have been criticized socially and had faced social stigma from local people (Bodrud-Doza et al, 2020), it was likely that perceptions of the virus could induce anxiety in workers in the course of service delivery. The chance for limiting the spread of any epidemics was much higher during the early stages, and providing useful information for public health policymakers could only be achieved through data collection (Shabu et al., 2020). Consequently, the present study was designed to shed more light and add value to strategies on facilitating adaptive behavioral change in workers as they make desperate efforts at the frontline to withstand the deadly pandemic and serve the public

2. Review of Literature

- The concept of risk perception cannot be explained without an understanding of perception, which is the way we experience sensory inputs about the world around us. Perception is a core variable that enables the interpretation of sensory experiences in order to inform necessary action and it is very important in information reception and interpretation with regards to the corona virus disease. Risk is any hazard, vulnerability, exposure to danger that can cause potential harm to a person or community, and it has been recognized as a mental model considering that individuals and communities respond differently to risk factors. With more precision, risk perception refers to individuals’ thinking and feeling about the risks they face with regards to the virus and this determines different health outcome behaviors and possible success of health intervention programs. Ferrer and Klein (2015) observed that risk perceptions may also have implications for overall well-being as threats unfold since evidence demonstrates that individuals with high risk perceptions are associated with poorer wellbeing. This concurred with the current model of study since focus is on negative reactions to risk perception of the virus by workers. Therefore, understanding risk through perception and giving meaning to it by the people living in a particular area provides useful perspectives for developing risk management strategies that are tailored to specific needs of the people (Mañez, Carmona, Haro, & Hanger, 2016). Risk perception is not only reflected in psychometric forms because it has a core relationship with the psychology of individuals, social and cultural realities of a people. On this basis, risk is highly subjective and depends on the experiencing subject, as individuals will only handle and respond to the risks that they perceive. This no doubt facilitates the development of risk management strategies that are tailored to local needs of the people.Some studies have been realized in the domain of risk perceptions to understand different responses by individuals and groups to health pandemics. With regards to the 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, Bults et al. (2011) reported that perception of risk and level of anxiety was high in the population, although they subsequently suffered from attenuation. Although the studies did not assess the relation between risk and the present virus, it is probable that the perception level of the pandemic could relate significantly with anxiety. Although the perceptions of risk of infections often have an influence on the adopted protective behaviors, perceived risks do not necessarily equal the actual risk experienced by subjects. In another study in Bangladesh, Bodrud-Doza et al. (2020) realized that 46.2% of the respondents were afraid of coronavirus diseases, 33.5% afraid of acquiring the disease and 45.6% of losing their life. Testing for effects, Bodrud-Doza et al. further observed that fear of getting infected, losing personal life or relatives and news of infection and deaths from friends induced anxiety. Fullana et al. (2020) revealed that perceived risk of job loss, having dependents, having COVID-19 symptoms with no diagnosis and having negative life-events were significantly associated with higher anxiety and depressive symptoms. In mainland China, Pan et al. (2020) found that chills, cough, dizziness, coryza, and sore throat were significantly associated with higher level of stress and anxiety. Although the target was not business operators and employees, it is possible that such categories of persons were among participants with the presumption of occupations. Although not directly on risk perception it was possible that anxiety and depression might have resulted from the way they perceive symptoms of the diseases such as cough and breathing. The consequences of COVID-19 on mental health of workers equally compromised their resistance due to isolation and loss of social support, risk or infections of friends and relatives as well as drastic changes in the ways of working (Sofia at al., 2020). The pandemic had been associated with fear and worry due to perceived inability to show control, mastery, and perhaps as a result of the way information about the virus was being processed and given meaning. Therefore, responsive strategies on the management of the disease by individuals become imminent in the context of the pandemic. Investigating risk perception and behavioral responses, Shabu et al. (2020) reported that a high ability to immediately avoid infection, risk of getting infection, serious illness, and death were high in participants. Khosravi (2020) further proposed that in order to effectively tackle such problems, it is necessary to implement non-medical measures such as the promotion personal protection practices, use of face masks, respect of personal hygiene, imposing travel restrictions and maintaining social distance from possibly infected cases. Although such external control measures are essential, positive perceptions, resilience, self-efficacy, trust and hope could be useful in building competence. The concept of performance anxiety came into play as the consequence of perceived risk of COVID 19. This implied that in occupational setting, the experience of anxiety, a mental health menace experienced by economic operators in all sectors could depend on risk perception. To Özdin and Özdin (2020), health anxiety was a multifaceted phenomenon, consisting of distressing emotions, physiological arousal associated with bodily sensations, thoughts and images of danger, avoidance, and other defensive behaviors. Cheng & McCarthy (2018) further defined workplace anxiety as feelings of nervousness, uneasiness, and tension about job performance and emotional state reflecting nervousness, uneasiness, and tension about specific job performance episodes. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown increase anxiety and depressive symptoms (Fullana, Mazzei, Vieta, Radua, 2020; Pan et al., 2020), and workers in different economic activities in different sectors were inclusive. Following a survey in Japan, Shiina et al. (2020) revealed that 11.7% participants presented no anxiety of being infected and transmission to others, while 10.8 % showed no worry about symptomatic aggravation while 8.1% did not indicate serious concern about expanding infection in the face of the disease. Furthermore, correlation results showed that participants were not anxious about the disease and protective behaviors. Sofia et al. (2020) also reported the prevalence of anxiety at 23·21% following thirteen studies. Although the study did not extend to performance issues at work or in business, results had implications on business founders and workers in the economic sector. Özdin and Özdin (2020) also found that females’ chronic disease and previous psychiatric symptoms predicted health anxiety during the corona virus. Although anxiety has been examined extensively with the public in the face of COVID-19, those in occupations have not yet been targeted although they were vulnerable with consequences.Many theories had been used to explain the relationship between risk perception and outcome behaviors. The Health Belief Model (HBM), developed by Hochbaum, Rosenstock and Kegels in the 1950 has stood the test of time in explaining outcome behaviors in face of treating diseases (Costa, 2020). The HBM states that outcome behavior is highly dependent on perceptions or beliefs about the severity of the disease condition, susceptibility to the condition and the activities necessary for preventing the condition. In order to adopt a desired health care behavior or avoid risks for diseases, the patient must: (1) believe to be susceptible to the disease, and this refers to individual belief of likelihood of getting the disease, and the higher the perceived likelihood, the higher the perceived susceptibility, (2) believe that the disease will negatively impact, at least moderately, their life, and this is the belief of the person about the extent to which getting that adverse health condition can affect him in terms of pain, death, finances, job or causing family problems, (3) believe that a particular course of action available would reduce the susceptibility or severity or lead to other positive outcomes, (4) perceive few negative attributes related to the health action. The supplementary component of self-efficacy could be successfully used since individuals’ belief in self to execute expected behavior required to produce the outcome is essential. Abraham and Sheeran (2014), asserted that the model could be applied to a range of health behaviors and it is capable of providing a framework for shaping behaviors relevant to public health care and treatment.This psychological model attempts to explain health behaviors from the aspects of individuals’ representations of health and health behavior, which are threats to perceptions and behavioral evaluation within the context of COVID-19. The HBM makes efforts to explain and predict health behaviors in terms of perception of the severity of corona virus and individuals’ vulnerability to the disease. Although consensus regarding the utility of the HBM was important for public health research (Abraham and Sheeran, 2014; Costa, 2020), current interest is on occupational health that falls within the context of wider public health domain since corona virus is a public health menace. This justifies the present emphasis on perceived susceptibility and severity of the disease since they determine workers’ perceived threat of the disease condition from the stand point of anxiety. It holds that a high perception of the threat of the disease leads to a high sense of danger such as emotional disorders and cognitive disorientations. Susceptibility also implies that individuals believe that the disease will negatively impact their life, and this is the case with the assumption of anxiety experience by workers in the face of corona virus.

2.1. Model of the Study

- The foregoing literature reveals that some studies have established significant relationships between risk perception and anxiety within the context of public health, but this was not necessarily with workers and anxiety drawn during performance. In this light, Kaulu et al. (2020) intimated that as a world pandemic authorities in many countries need to provide effective responses to the overwhelming burden that COVID-19 places on human life, economic activities and financial system. The need for information for action no doubt necessitates the present study on risk perception and performance anxiety among people who are active in the world of work. Despite the recognition that social, institutional and cultural processes influence individuals’ perceive risk and resultant responsive behavior (Kaulu et al., 2020), the current task assessed the link between perception of the virus and psychological distress experienced by people in occupations during the pandemic. Since the experience of uncertainty can increase anxiety levels of individuals, especially when there is potential risk for mortality (Shiina, et al., 2020), perceived risk factors could heighten the claim that risk perception of the virus is capable of predicting anxiety in workers. More to that the study argues that perceived severity of the virus by workers constitutes health and safety risk in the process of business interaction and could lead to nervousness and tension with consequences on productive economic behaviors. Despite the understanding that the worry over getting a disease could influence perceived risk of the pandemic (Khosravi, 2020), the current orientation has identified risk perception as a predictor capable of explaining variability in performance anxiety. Many studies have focus on risk and preventive behaviors (Shabu et al., 2020) overall wellbeing (Ferrer and Klein, 2015) and behavioral responses (Kaulu at al., 2020; Shabu et al., 2020), but no systematic investigation had been observed yet by the investigator on performance anxiety, particularly in the Cameroon context. Therefore, the study was designed to find out if perceptions of corona virus and perceived ability to manage the disease can influence anxiety in workers during their operations.

3. Methodology

- To understand the link between risk perception and performance anxiety among workers in Bamenda with the outbreak of COVID 19, a cross-sectional survey was adopted. The study targeted employees and self-employed workers in the informal sector in Bamenda municipality since necessity compelled them to operate with the outbreak of the pandemic. Data were gathered through questionnaires the recruitment 260 employees and self-employed workers through convenience sampling. Due to restriction of movements and interactions due to the pandemic, the workers were recruited in the neighborhoods, work and business premises. The sample constituted 38.8% employees and 62.2 self-employed workers (males 53.5%; females 46.5%) with age range, 20-60, and dominated by employees between 20-40 years. Furthermore 38.8 participants work for organizations while 61.2% operate in the private sector. Again, 31.9% deliver services in the public sector while 68.1 operate in the private sector of the economy. In terms of measures for data gathering, relevant items were considered based on the socio-economic and cultural realities particularly their thinking, feelings and practices in the face of the pandemic. The questionnaire included established and validated scales.Risk perception was operationalized and measured in terms of meaning given to an object (Mañez et al., 2016), and this was how participants thought and felt about the risk of corona virus. The sub-scale comprised 7 items with the following sample questions: “I have the feelings that COVID-19 is very severe,” “I look at COVID-19 as a fearful.” Using a four point approach the measure was coded and scored to assess prevalence of risk perception: Strongly Disagree=1, Disagree=2, Agree=3 and Strongly Agree=4. The internal reliability analysis for the sub-scale was performed (M = 36.31, SD = 9.758, α = 0.943).Perceived controllability was defined as perceived competence of participants to control or manage the disease (Khosravi, 2020), and measure was designed to assess ability of participants to control/cope with the exigencies of corona virus. Sample items: “I believe that COVID-19 is a disease that can be managed,” “I feel I can cope with the risk I take during COVID-1.” Using a four point approach the measure was coded and scored as follows to assess prevalence of symptoms as follows: Strongly Disagree=1, Disagree=2, Agree=3 and Strongly Agree=4. The internal reliability analysis for the sub-scale was performed (M = 21.56, SD = 4.523, α = 0.808).Performance anxiety was operationalized in terms of feelings and emotional state reflecting nervousness, uneasiness, and tension about job or business performance (Cheng & McCarthy, 2018), and the measure of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, and Lowe, 2006) was adopted to assess prevalence. Sample items: “During COVID-19, I feel worried a lot about different things concerning my work/business” and “I feel so restless that it is difficult to concentrate and do work/business during COVID-19.” Using a four point scale the measure was coded and scored to assess prevalence of symptoms: not at all sure=0, several days=1, over half the days=2 and nearly every day=3. The internal reliability analysis for the sub-scale was performed (M = 19.77, SD = 4.406, α = 0.820). It would be noted that the alpha for all the sub-scales comprising 22 items were computed with an aggregate reliability coefficient of 0.853. With regards to administration, the data were collected in April 2020 by the investigator, while assistance was sort from Masters Students in Psychology and Clinical Counseling. An orientation meeting was organized with participants who were briefed on the goal of study, sensitivity of the investigation, ethical codes and codes of interaction with participants on the field with the arrival of the pandemic in Bamenda. The participants were requested to participate on the study and were informed that their involvement in the exercise was voluntary and they could withdraw at any time if necessary. At the end we received 260 completely filled questionnaires out of 300 making a participation rate of 86.66%. Data were entered into SPSS and descriptive and inferential statistics used for analysis.

4. Results of the Study

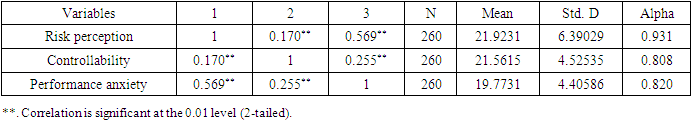

- Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlation analysis among study variables have been presented on Table 1. The mean of risk perception (M=21.9231; SD=6.39), perceived controllability (M=21.56; SD=4.52) and performance anxiety (M=19.77; SD=4.40) showed that risk perception of the virus and perceived controllability were higher than performance anxiety.

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- The interest of the present study was to investigate if risk perception of corona virus by workers will affect performance anxiety of workers. Firstly, the inter-correlation analysis among the study variables; perception of corona virus, perceived controllability and performance anxiety were positively significant showing the relevance and congruity among the hypothesized model tested by the study. Also, the mean and standard deviation showed the high prevalence of cognitive and emotional states of workers with the outbreak of the pandemic. This is consistent with the recognition that getting the disease can influence a perceived risk of a pandemic (Khosravi, 2020), and this is usually manifested by unpleasant emotions in the likes of fear, tension and worry associated by workers with consequences on their performance. In the first place, regression analysis revealed that perception of the virus as a risk factor significantly predicted performance anxiety among workers with the advent of the pandemic, and the weight of the effect was high. This implies that the way workers and business operators think and feel about the risks involved in business interactions in the face of the virus induces unpleasant emotions. Results are in conformity with Ferrer and Klein (2015) on risk perceptions and poor well-being and Bults et al. (2011) on risk perception and high level of anxiety in participants during the 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. Analysis further concured with recent studies in the context of COVID-19 on risk and infection, illness, and death (Shabu et al., 2020), fear of coronavirus, anxiety, and death (Bodrud-Doza et al., 2020), chills, cough, dizziness, coryza, and higher level of stress and anxiety (Pan et al., 2020). The findings of Fullana et al. (2020) on perceived risk of job loss, negative life-events, and higher anxiety and depressive symptoms went further to support the findings of the study. On another note, results contradict Shiina et al. (2020) where no anxiety of infection and transmission was observed with participants and their concern was more about protective behaviors. Conformity of the results with prior findings could be attributed to the fact that the breakout of the disease was wild, through medias and horrors were observed that were scary in other countries before it arrived Cameroon. The accelerating spread of COVID-19 and its outcomes around the world had led people to experience fear, panic, concern, anxiety, stigma and depression (Bodrud-Doza et al., 2020). Therefore, knowledge and beliefs about the pandemic as a person-to-person transmissible virus was a big blow to workers since all economic activities are patterns of human behavior, and interactions in service delivery processes inevitable. In the informal sector in Bamenda most of the enterprises and small scale businesses are dominated by petty trading where actors cannot get into online business activities such as e-commerce and tele-meetings, and depend purely on human interactions, which is a possible route for the spread of the virus. In terms of competence to manage COVID 19, perceived controllability predicted variation in performance anxiety. Therefore, the perceived ability of workers to manage the virus had an influence on their level of anxiety in human interactions while operating their economic activities. Results were consistent with Sofia at al. (2020) that mental health of workers stand to affect the way people personally manage stress experiences resulting from the perceived risk of corona virus disease. The current findings are supported by Khosravi (2020) that the implementation of non-medical measures such as the promotion of personal protection practices and social distancing are necessary. Alternatively, the present findings are in disaccord with Shabu et al. (2020) that a high ability to immediately avoid infection, risk of getting infection, serious illness, and death were high in participants during the pandemic indicating preventive attitudes and behavior. Risk perceptions are also reliably influenced by contextual factors. For example, as looming threats become more immediate, a risk perception tend to become more pessimistic and tends to be higher when a health threat is seen as uncontrollable or dreaded (Ferrer and Klein, 2015). Although such external control measures are critical, positive perceptions, resilience, self-efficacy, trust and hope could be very useful in building behavioral competence despite the recognition that the speed and horror ignited by the spread of the virus could have moderated psychological resources of workers to manage the disease.

6. Implications and Conclusions

- The theoretical implication of the study cannot be undermined. The meaning given to risk in terms of severity and susceptibility of the disease and behavior outcome suggested predictive utility of the Health Behavior Model (HBM) used in the study. The HBM explained the relationships with the understanding the determinants responsible for people’s resistance to protective measures against the virus spread was of great importance for the effectiveness of policy implementations social controls (Costa, 2020). Apart from the ecological validity of the model, findings from the study could contribute to ongoing body of psychological knowledge and techniques in the behavioral management of COVID 19 with particular emphasis on risk perception and anxiety. Some studies have used the HMB in the context of the virus (Costa, 2020), and although focus was on preventive behavior outcome, its relevance was demonstrated in the process of predictive utility with regards to performance anxiety as occupational health behavior outcome. The model explained the suggestion that corona virus was perceived as a big threat as workers are susceptible to anxiety experiences and this was also due to perceived severity of the disease. This shows that the HBM was relevant to context and could be used to explain related behaviors in intervention initiatives. The findings also had significant policy and practical implications with regards to interventions designed to arrest the spread of the virus. The study was pertinent and relevant considering that early studies on the disease could reinforce current measures advanced by the government to prevent the spread of the virus. Kaulu et al. (2020) posited that with the world pandemic, authorities in many countries need to provide effective responses to the overwhelming burden that COVID-19 places on human life, economic activities and financial system. Furthermore, the study assisted with strategies in alleviating psychological distress among persons at work, both employees and self-employed in different sectors of the economy. Information and knowledge generated on risk perception and performance anxiety in the face of the evolving pandemics may be used to encourage the activation of certain attributes and internal resources to comply and adjust to commendable adaptive behavior. It was therefore expected that the study would contribute to on-going practices in holding the spread. This also involves a careful guidance to provide human-friendly policies and interventions to promote adaptive and resilient patterns capable of evading the high risk of the infection. In some cases in which the perception of risk is framed by historical and social events, risk awareness and perception are high, and people and institutions show enhanced preparedness in order to reduce potential harms (Mañez et al., 2016). This is not the case with the current study considering that traumatic events can reduce people’s feeling of security, remind them of death and have adverse effects on their mental health (Özdin and Özdin, 2020). This could explain the current results where workers appear to be overwhelmed with fear and danger of the disease and this in many ways affected their potentials to cope with imminent threat from the disease and this no doubt requires clinical therapeutic interventions. It is possible that feelings of powerlessness could have been aggravated by perceived unproductive economic activities or performance as perceived risk heightened tension and despair. It is therefore necessary to design packages to support business activities in times of crisis in order to reduce the phenomenon of double stressors from coping with the exigencies of the pandemic and dwindling economic results. With the understanding that risk is perceived differently by people, risk management approaches are influenced by what people perceive as risky and if a hazard is perceived as a potential risk, the respective actors will take action to manage the disease (Mañez et al., 2016). There is no gainsaying that the present study recorded come limitations in the process of investigation and analysis. The cross-sectional study used convenience sampling, and could not reach out to reasonable strata of the population in the sample. Furthermore, the scope of the study was limited to risk perception of COVID-19 and anxiety, and this might have limited analysis and information that could have implications on the management of the virus. In addition, data collection depended on adopted tests and questionnaire items that are often too restrictive and dogmatic, and no opportunity was given to participants through key informant interview or Focus Group Discussion (FGD). This is coupled with the fact that experiences of workers were self-reported and this might have led to social desirability bias. Despite the perceived limitations, the study was well conceived, designed with data collection instrument that had good reliability analysis and collected results using standard procedures and ethical codes that yielded the present results. With the outbreak of corona virus disease, it was challenging for most businesses across the world to keep their financial wheels rolling, given reduced revenues and the high level of uncertainty (Vermaa and Gustafsson, 2020) due to perceived risk of interactions during business transactions. With the recognition that medical staff suffers adverse psychological disorders, such as anxiety, fear and stigmatization (Qiu, Chen and Shi, 2020), it was likely that workers caught in between service provision and risk of interactions during the pandemic will suffer clinical symptoms due to perceived risk of the disease. Many factors determine risk perception and influence from perceived risk of COVID 19 could take different dimensions. Although Khosravi (2020) observed that people’s risk perception of the pandemic is one of the factors contributing to an increase in public participation in adopting preventive measures, the present study has instead reported unpleasant emotional experiences with variations on anxiety. There is no doubt that health authorities in many countries had provided recommendations for coping with the exigencies of the disease in many ways. This is laudable, but the study suggested that non medical measures with focus on behavior change strategies appeared optimistic to workers in playing safe and carrying on with their economic activities. From all indicators, the threat to workers’ health was real, and consequences on business operation could not be undermined. This expressed a need for increased attention on emotional exaction of workers, and at the same time on their psychological resources as facilities to control and successfully manage preventive measures. Although the stormy drive and destructive intent of the virus is historically demoralizing and tension-inducing, Bults et al. (2011) observed that the public should always remain calm and comply with preventive measures. Furthermore, it was necessary to understand and investigate the public psychological states during this tumultuous time (Yenan et al. 2020). This is why the results of the survey were considered of great practical relevance in terms of information provision, cognitive and behavior guidance and psychological support to employees and self-employed workers.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML