-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2022; 12(2): 18-24

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20221202.01

Received: Jun. 30, 2022; Accepted: Jul. 27, 2022; Published: Aug. 15, 2022

How Can “Autonomous Self-Esteem” be Assessed and Cultivated?

Katsuyuki Yamasaki1, Takayuki Yokoshima2, Daisuke Noguchi3, Kanako Uchida1

1Department of Psychology and Educational Science, Naruto University of Education, Naruto-shi, Tokushima, Japan

2Center for Student Support, Shikoku University, Tokushima-shi, Tokushima, Japan

3Department of Early Childhood and Elementary Education, Nakamura Gakuen University, Fukuoka-shi, Fukuoka, Japan

Correspondence to: Katsuyuki Yamasaki, Department of Psychology and Educational Science, Naruto University of Education, Naruto-shi, Tokushima, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper follows Yamasaki, Uchida, Yokoshima, and Kaya’s (2017) classification of self-esteem into autonomous and heteronomous self-esteem. Autonomous self-esteem is adaptive and healthy, whereas heteronomous one is nonadaptive and unhealthy. First, several implicit association tests (IATs) were introduced to assess both types of self-esteem. Autonomous self-esteem, in particular, needs to be measured using certain nonconscious assessment tools. Thereafter, from the necessity to enhance autonomous self-esteem, programs to cultivate it, which belong to a group of the programs collectively termed “TOP SELF (Trial of Prevention School Education for Life and Friendship), were depicted in terms of their purpose structure and methods for lower- and higher-grade students in elementary and junior-high schools. Moreover, to reveal the effectiveness of the programs, the results of the previous empirical studies among the lower- and higher-grade students were shown. Lastly, future avenues to widely disseminate the programs were discussed, underscoring the importance of students’ health and adaptation in schools.

Keywords: Autonomous self-esteem, Heteronomous self-esteem, Implicit association test, Universal prevention program, School

Cite this paper: Katsuyuki Yamasaki, Takayuki Yokoshima, Daisuke Noguchi, Kanako Uchida, How Can “Autonomous Self-Esteem” be Assessed and Cultivated?, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 12 No. 2, 2022, pp. 18-24. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20221202.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Self-esteem is still a popular topic in psychology and education. Specifically, school teachers have been interested in cultivating children’s self-esteem. However, the concept of self-esteem is confusing. Owing to inconsistent findings in several studies on the benefits of self-esteem (e.g., Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003; Emler, 2001), new concepts have been proposed. For instance, Deci and colleagues (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1995) introduced the concepts of “true” and “contingent” self-esteem, and Kernis (2003) divided it into “fragile” and “secure” high self-esteem. These two types were developed to discriminate between healthy (adaptive) and unhealthy (nonadaptive) self-esteem. In line with this consideration, self-esteem that previous research has been investigating can include both the undivided types. In recent years, Yamasaki et al. (2017) proposed new concepts of self-esteem: “autonomous” and “heteronomous” self-esteems. The uniqueness of their classification remains in underscoring the importance of nonconscious nature of autonomous self-esteem. This paper aimed to introduce the concept and measurement of autonomous self-esteem and educational programs for cultivating it and reveal the effectiveness of these programs.

2. What is Autonomous Self-Esteem? and How Can It be Measured?

- As stated above, Yamasaki et al. (2017) classified self-esteem into autonomous and heteronomous ones. They considered that autonomous self-esteem consists of high levels of self-confidence, confidence in others, and intrinsic motivation—these three components at a high level are indispensable for autonomous self-esteem. Meanwhile, heteronomous self-esteem is characterized by low levels of these three components. Moreover, they proposed that autonomous self-esteem cannot be consciously measured using self-report questionnaires, although heteronomous self-esteem can be. Namely, autonomous self-esteem needs to be nonconsciously (implicitly) assessed using certain methods other than self-reports. Even heteronomous self-esteem is more precisely measured using nonconscious methods. After introducing these concepts of self-esteem, Yamasaki (2019) suggested that Rosenberg’s (1965) Self-Esteem Scale cannot measure desirable self-esteem he proposed, though the scale has been most frequently used globally. More specifically, his scale should not be used because it includes elements of both desirable and undesirable self-esteem that cannot be distinguished. This proves certain methods to assess autonomous self-esteem are needed. Yamasaki et al. (2017) suggested the Implicit Association Test (IAT) as an assessment method. In the IAT, the implicit association between two kinds of stimuli is measured using indices of speed and accuracy of reactions (e.g., Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). Although a few IATs have been developed for self-esteem (e.g., Jordan, Spencer, Zanna, Hoshino-Browne, & Correll, 2003; Zeigler-Hill, 2006), the IAT by Yokoshima, Uchiyama, Uchida, and Yamasaki (2017) was the first to measure autonomous self-esteem. It was termed “the paper and pencil version of Self-Esteem Implicit Association Test for Children (SE-IAT-C). The SE-IAT-C was developed to examine the effectiveness of programs to cultivate autonomous self-esteem in elementary school students, overcoming the limitations of previous IATs. The reliability and validity of the test were confirmed by Yokoshima et al. (2017). The reliability was measured through test-retest correlations and the validity through homeroom teachers’ evaluations of their students in terms of autonomous self-esteem.The SE-IAT-C was used for the assessment only of autonomous self-esteem and had the limitation that it is not considered for the measurement of confidence in others. So, Yokoshima (2022) revised this IAT to remove the limitation and simultaneously assessed heteronomous self-esteem. As of now, this new version, the tablet PC version of the Autonomous and Heteronomous Self-Esteem Implicit Association Test for Children (AHSE-IAT-C) developed by Yokoshima (2022) was confirmed to be reliable and valid for 4th- and 5th-grade elementary school students. Moreover, Yokoshima, Noguchi, Kaya, and Yamasaki (2021) developed the modified paper version of the AHSE-IAT-C for lower-grade elementary-school students (1st- and 2nd-grade students) using pictograms.

3. How is Autonomous Self-Esteem Cultivated in Schools?

- The core of autonomous self-esteem is developed in early childhood (Yamasaki, 2017). When infants feel physiological or psychological needs or desires and express them through some signals or signs, caregivers need to satisfy them immediately with enough affection. Through this experience, infants acquire self-confidence and confidence in others. Moreover, as no external controls are found in this experience, intrinsic motivation is kept high. Generally, external controls, such as punishments and rewards, often change an intrinsic motivation into an extrinsic one (e.g., Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973). This kind of development proceeds with infants’ own experiences without receiving any conscious instruction. Children with low autonomous self-esteem lack this kind of experience. Namely, the reactions of caregivers toward infants’ signals are not appropriate. In this case, childen’s personality becomes attuned to heteronomous self-esteem or apathy, and passivity. Because of the fundamental process to form autonomous self-esteem, elementary school students with low autonomous self-esteem should be helped to follow a similar process to acquire autonomous self-esteem. In doing so, we should avoid teaching students through direct verbal instructions and guidance. Instead, students need to experience the process through classroom activities. Moreover, they should be engaged in classes with high motivation to participate. In this process of cultivating autonomous self-esteem, a group of new educational programs termed “TOP SELF (Trial of Prevention School Education for Life and Friendship)” (see Uchida, Yamasaki, & Sasaki, 2014; Yamasaki, Murakami, Yokoshima, & Uchida, 2015, for details) can be utilized. Briefly, the background theory of TOP SELF states that cognition (or thinking), feelings, and behaviors are appropriately learned and memorized only in combination with emotions that are primarily unconscious physiological reactions as suggested by the somatic marker hypothesis (Damasio, 1994, 2003). The purposes of the programs in TOP SELF are hierarchically structured with the methods consisting of various games, activities, and music that are enjoyable enough to capture students’ attention. Thus, the programs for cultivating autonomous self-esteem were developed under the theories and methods of TOP SELF, which means that the programs belong to one of the programs of TOP SELF. In addition, the newest version of TOP SELF has made it easier for teachers to implement programs, maintaining the effectiveness and attractiveness for children. The programs for cultivating autonomous self-esteem adopt the characteristics of the newest TOP SELF.

4. The Structure and Main Purposes of the Programs

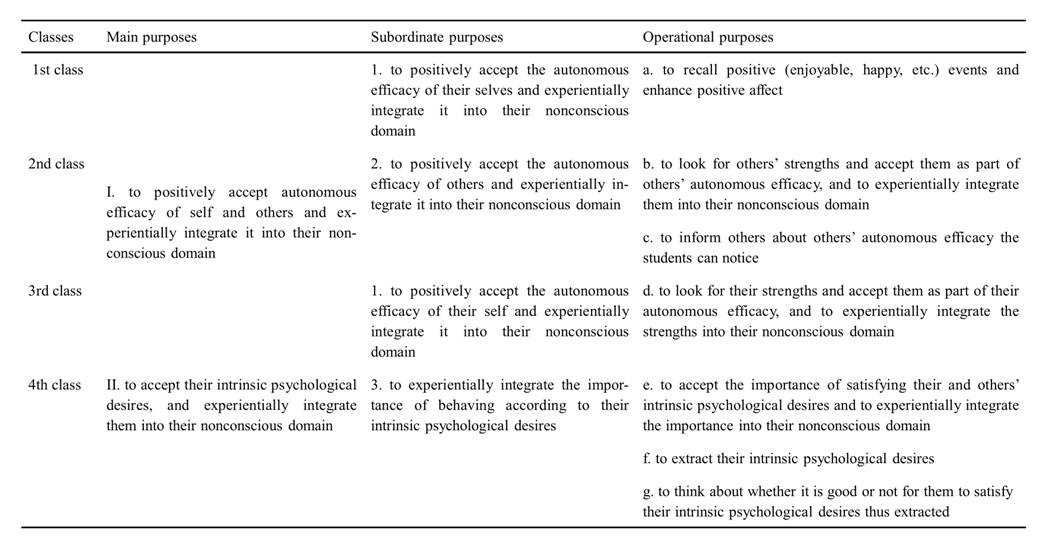

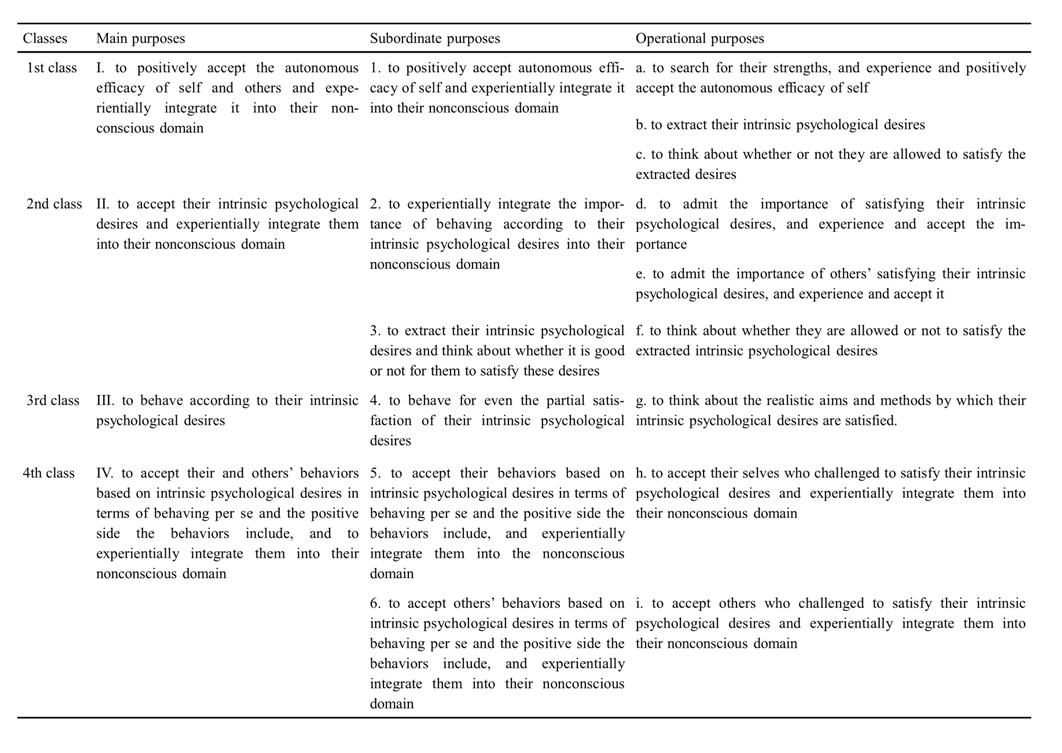

- The main purposes of the program for autonomous self-esteem are the cultivation of the following capabilities in students: (I) to help students positively accept the autonomous efficacy of their selves and others and experientially integrate it into their nonconscious domain; (II) to help students accept their intrinsic psychological desires and experientially integrate them into their nonconscious domain; (III) to help students behave according to their intrinsic psychological desires; and (IV) to help students accept their and others’ behaviors based on intrinsic psychological desires in terms of behaving per se and the positive side the behaviors include, and experientially integrate them into their nonconscious domain. In this case, autonomous efficacy represents a psychological characteristic leading to thoughts and feelings that they can act to satisfy whenever their intrinsic psychological desires arise. The programs for cultivating autonomous self-esteem can be applied to the students from the first grade of elementary schools to the first grade of junior high schools. Some of the programs are under development now, but the four-class versions for the first- and second-grade elementary school students, for the fifth- and sixth-grade elementary school students, and for the first-grade junior high school students have been completed. In this paper, the program for the first and second grades of elementary school is termed “the program for lower-grade students,” and the program for the fifth and sixth grades of elementary school and the first grade of junior high school is termed “the program for higher-grade students.”These two types of programs include the partially-different purpose structures. Tables 1 and 2 show the purpose structures from the main to operational purposes in the programs for lower- and higher-grade students, respectively. Although the program for higher-grade students includes all four main purposes, the main purposes of the program for lower-grade students are limited to two of them. The subordinate and operational purposes are decided depending on which main purposes are selected.

5. The Subordinate and Operational Purposes and Class Contents in the Program for Lower-Grade Students

- As Table 1 shows, the main purposes I and II were selected in the program for lower-grade students. The main purpose I was selected for the 1st to 3rd classes, and the main purpose II was selected for the 4th class.

| Table 1. The Hierarchical Structure of the Purposes of the Programs for Lower-Grade Students |

6. The Subordinate and Operational Purposes and Class Contents in the Program for Higher-Grade Students

- As Table 2 shows, all main purposes were adopted in the program for higher-grade students. The main purposes I to IV were considered in the program for the 1st to 4th classes, respectively. In the 1st class, the subordinate purpose is to help the students positively accept autonomous efficacy of their selves and experientially integrate it into the nonconscious domain, and the operational purposes are to help them search for their strengths, experience and positively accept autonomous efficacy of their selves, extract their intrinsic psychological desires, and think about whether or not they are allowed to satisfy their extracted desires. In this class, the students think of their dreams and aim twenty years ahead and write about the potential troubles and failures to achieve them on their worksheets. Then, after sharing their writings, they put forward their advice or messages to support the realization of their dreams to each other in their small groups. Thereafter, similar activities are conducted in the whole class for them to enjoy the panel game.

| Table 2. The Hierarchical Structure of the Purposes of the Programs for Higher-Grade Students |

7. The Effectiveness of the Programs

7.1. The Effectiveness of the Program for Lower-Grade Students

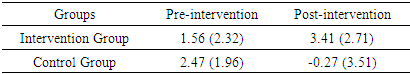

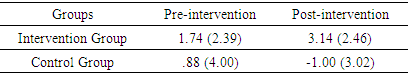

- As stated before in this paper, the effectiveness of the programs is assessed using the IATs because any explicit measure such as self-report questionnaires cannot capture the nonconscious core characteristics of autonomous self-esteem. The IAT is the AHSE-IAT-C. Its pictogram version is used for lower-grade students owing to their insufficient understanding of written words. First, Noguchi, Yokoshima, Kaya, and Yamasaki (2021) examined the effectiveness of the program in the second-grade students. The intervention and control groups consisted of 54 students (30 boys and 24 girls) and 26 students (14 boys and 12 girls), respectively. The short version of the program was presented to the students in the intervention group, once per week for successive four weeks. The IAT was administered to the intervention group just before and after the intervention and to the control group around the same period as the intervention group. The results were shown in Table 3. Statistical analyses using the analyses of variances (ANOVAs) revealed that among both boys and girls, the scores in the intervention group were significantly higher than those in the control group in the post-intervention period, and there was no significant difference between the two groups in the pre-intervention period. The results suggested that autonomous self-esteem was enhanced by this program, simultaneously showing a decrease in heteronomous self-esteem.

|

7.2. The Effectiveness of the Program for Higher-Grade Students

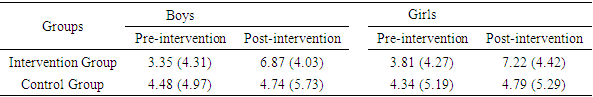

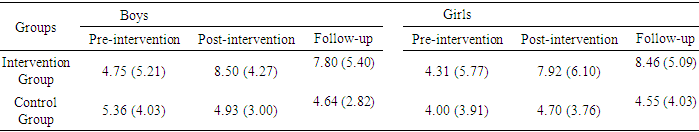

- Yamasaki, Yokoshima, and Uchida (2022) examined the effectiveness of the program for higher-grade students. Fifty-five fifth-grade students (23 boys and 32 girls) and sixty 5th-grade students (31 boys and 29 girls) were allocated to the intervention and control groups, respectively. A short version of the program for enhancing autonomous self-esteem was presented to the intervention group. The program was implemented weekly for four consecutive weeks in regular 45-minute classes for all homeroom class members in the intervention group. In the intervention group, pre- and post-intervention evaluations were conducted in the classes approximately one week before the start of the program and after the end of the program, respectively. Participants in the control group were given evaluations around the same period as those in the intervention group were given. The measure was the AHSE-ATE-C.Results are shown in Table 5. Statistical analyses using the ANOVAs revealed that among both boys and girls, the scores in the intervention group were significantly higher than those in the control group in the post-intervention period, with no difference between the two groups in the pre-intervention period. This proves the similar effectiveness of the program to that for lower-grade students. Moreover, the effectiveness did not change regardless of the level of autonomous self-esteem before the implementation.

|

|

8. Future Avenues to Disseminate the Programs

- Self-esteem is one of the popular topics at schools. School personnel attempt to enhance the self-esteem of students for their health and adaptation. However, the self-esteem which they target is often unhealthy and nonadaptive like heteronomous self-esteem. Especially, as they utilize self-reports to measure self-esteem, the assessed contents tend to come from heteronomous one. Considering this, school personnel need to be careful about the concept and assessment tools of self-esteem. The current paper depicted what healthy and adaptive self-esteem is and introduced the assessment tools and programs to enhance it. To explain the true concept of self-esteem to school personnel does not appear to be difficult, but to use the IATs as assessment tools for true self-esteem would be difficult. Although self-reports are easy for administering and scoring, the IATs introduced here are also not so difficult to do so. It takes about 15 minutes to complete, and the scoring does not take much time as it is automatically done by PCs. The core of autonomous self-esteem is developed in early childhood, but most students are growing apart from its complete development. So, if some elementary-school students need to modify and enhance self-esteem in terms of autonomous one, the programs in this paper can be utilized, covering most grades in schools. In schools, academics are underscored, but we know that health and adaptation are more important than academics. Moreover, health and adaptation are the bases for academics. School personnel should reconsider what is most important for their children. We hope that the concept, assessment, and programs will be widely disseminated in schools in Japan, expecting that the program will be conducted on a regular basis in all schools.

Disclosure Statement

- The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Funding

- This article was funded by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number 21K03107.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank many teachers and children for their contribution to conducting the programs.

References

| [1] | Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1-44. |

| [2] | Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes' error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam. |

| [3] | Damasio, A. R. (2003). Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow and the Feeling Brain. New York: Harcourt. |

| [4] | Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1995). Human autonomy: The basis for true self-esteem. In Kernis, M. H. (Ed.), Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem (pp. 31-49). New York: Plenum Press. |

| [5] | Emler, N. (2001). Self-esteem: The costs and causes of low self-worth. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. |

| [6] | Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102, 4-27. |

| [7] | Jordan, C. H., Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., Hoshino-Browne, E., & Correll, J. (2003). Secure and defensive high self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 969-978. |

| [8] | Kernis, M. H. (2003). Toward a conceptualization of optimal self-esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 1-26. |

| [9] | Lepper, M., Greene, D. & Nisbett, E. (1973). Undermining children’s intrinsic Interest with extrinsic rewards: A test of the ‘overjustification’ hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28, 129-137. |

| [10] | Noguchi, D., Yokoshima, T., Kaya, I., & Yamasaki, K. (2021). The development and effectiveness of the program to cultivate autonomous self-esteem for lower-grade students in elementary schools. Poster session presented at the 63rd Annual Meeting of Japanese Association. of Educational Psychology. |

| [11] | Noguchi, D., Yokoshima, T., & Yamasaki, K. (in press). The effectiveness of the program to cultivate autonomous self-esteem for the first-grade students in elementary schools. Poster session presented at the 64th Annual Meeting of Japanese Association of Educational Psychology. |

| [12] | Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. |

| [13] | Uchida, K., Yamasaki, K., & Sasaki, M. (2014). Attractive, regularly-implementable universal prevention education program for health and adjustment in schools: An Innovation from Japan. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 754-764. |

| [14] | Yamasaki, K. (2017). A revolution for self-esteem: Why do society and schools like self-esteem so much? Fukumura Publishing Company. |

| [15] | Yamasaki, K. (2019). Why do researchers and educators still use the Rosenberg Scale? Alternative new concepts and measurement tools for self-esteem. Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science, 7, 74-83. |

| [16] | Yamasaki, K., Murakami, Y., Yokoshima, T., & Uchida, K. (2015). Effectiveness of a school-based universal prevention program for enhancing self-confidence: Considering the extended effects associated with achievement of the direct purposes of the program. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 5, 152-159. |

| [17] | Yamasaki, K., Uchida, K., Yokoshima, T., & Kaya, I. (2017). Reconstruction of the conceptualization of self-esteem and methods for measurement: Renovating self-esteem research. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 7, 135-141. |

| [18] | Yamasaki, K., Yokoshima, Y., & Uchida, K. (2022). Effectiveness of a school-based universal prevention program for enhancing autonomous self-esteem: Utilizing an implicit association test as an assessment tool. School Health, 17, 20-28. |

| [19] | Yokoshima T. (2022). Development of a brief implicit association test for autonomous and heteronomous self-esteem. In K. Yamasaki (Ed.), Reconstruction of research and education for self-esteem: From concepts and assessment methods to educational methods and evaluation (pp. 103-117). Kazamashobo. |

| [20] | Yokoshima, T., Noguchi, D., Kaya, I., & Yamasaki, K. (2021). A preliminary study on the paper version of the implicit association test using pictograms to measure autonomous and heteronomous self-esteem. Poster presented at the 63rd Annual Meeting of Japanese Association of Educational Psychology. |

| [21] | Yokoshima, T., Uchiyama, Y., Uchida, K., & Yamasaki, K. (2017). Development of the paper and pencil version of Self-Esteem Implicit Association Test for Children (SE-IAT-C): Investigation of the reliability and validity utilizing Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale and assessment of children by teachers. Journal for the Science of Schooling, 18, 1-13. |

| [22] | Zeigler-Hill, V. (2006). Discrepancies between implicit and explicit self-esteem: Implications for narcissism and self-esteem instability? Journal of Personality, 74, 119-143. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML