-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2021; 11(1): 6-12

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20211101.02

Received: Feb. 25, 2021; Accepted: Mar. 6, 2021; Published: Mar. 15, 2021

Relationship between ABO Blood Type and Personality in a Large-scale Survey in Japan

Masayuki Kanazawa

Human Sciences ABO Center, Tokyo, Japan

Correspondence to: Masayuki Kanazawa , Human Sciences ABO Center, Tokyo, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The influence of genetic factors on personality has been actively studied for several decades. However, there is no scientific consensus about the specific genes involved, since the previous studies using multiple-item measures yielded inconsistent results. In this study, we conducted an analysis based on the phenotype of the ABO gene using single-item measures with a large amount of data. The result of our large-scale survey (N = 3,750) showed that respondents displayed the personality traits corresponding to their own blood type more strongly than respondents who had different blood types did. This finding was consistent across all traits, and all differences were statistically significant. In our survey, the same differences in scores were found in the groups who had no knowledge of blood type personality theory, although the values were smaller. Meanwhile, the sample in this study was limited to Japanese populations. Additional research using a large, more global dataset is needed.

Keywords: Blood type, Personality, Big five, Large-scale survey

Cite this paper: Masayuki Kanazawa , Relationship between ABO Blood Type and Personality in a Large-scale Survey in Japan, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 11 No. 1, 2021, pp. 6-12. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20211101.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

- The influence of genetic factors on personality has been actively studied for several decades. Currently, the percentage is considered to be about 50% [1-3]. In order to improve accuracy, very large amounts of data such as various behavioral patterns and reactions are needed. Thus, the time, effort, and expense of examining over 20,000 human genes would have to be extremely large. Even if all those data were available, it would be very difficult to analyze these “big data” with conventional methods and approaches, and it would be especially difficult to obtain coherent and reliable results.An example is the relationship between variations of serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and subjective feelings of happiness. There are three types of 5-HTTLPR gene: the longest type, “long-long”; the shortest type, “short-short”; and the intermediate “long-short”, with individual and ethnic differences. A study of American people (N = 2,574) found that the ones who had “long-long” type of gene reported the highest subjective sense of well-being [4]. On the contrary, a study of Japanese people (N = 92) showed the opposite result, with “short-short” having the highest score [5]. Thus, much of the research that directly examines the association between genes and personality requires further investigation.In 2017, a meta-analysis of studies involving 260,861 subjects was published [6]. The researchers re-analyzed an association between the “Big Five” personality test and genes, and found that 6 genes affected human personality. However, the maximum magnitude, or the coefficient of determination, was as low as 0.04%. This value is usually considered to be an error.Nevertheless, among the many human genes, ABO blood type is one of the exceptions. Therefore, hundreds of studies have been conducted to date, and several studies have reported differences, mainly in Japan, Korea, China and Taiwan. One reason is that these studies usually used single-item measures, whereas the previous studies of genetic factors used multiple-item measures such as personality tests. Another reason is that many people in those countries know their ABO blood type, due to blood typing at birth, conscription, and blood donation, among other reasons. However, the type information available in self-reports in these studies is limited to phenotypes (A, B, O, AB), and does not include genotypes (AA, AO, BO, BB, OO, AB).

1.2. Blood Type Personality Theory

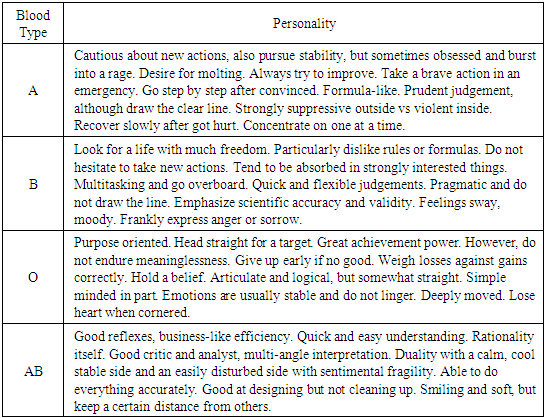

- The relationship between blood type and personality is studied at an international scale, and the first academic examination using statistics as a base was conducted in 1927, by Furukawa, a Japanese educational psychologist [7-12]. However, the paradigm that most influences present-day research is from a Japanese book [13] published in 1971 by Nomi, a Japanese independent researcher [9,11-12].Nomi’s research further developed Furukawa's theory (Table 1). He adopted the multiple method approach which consisted of questionnaires on the traits of people's behavior and mindset, surveys of blood type distribution for various occupations and groups, and observations of human behavior and statistical analyses. He also suggested an association with disease and physical constitution; for example, individuals with type B blood would be resistant to certain types of cancer [14-15].

|

1.3. Results of Previous Studies

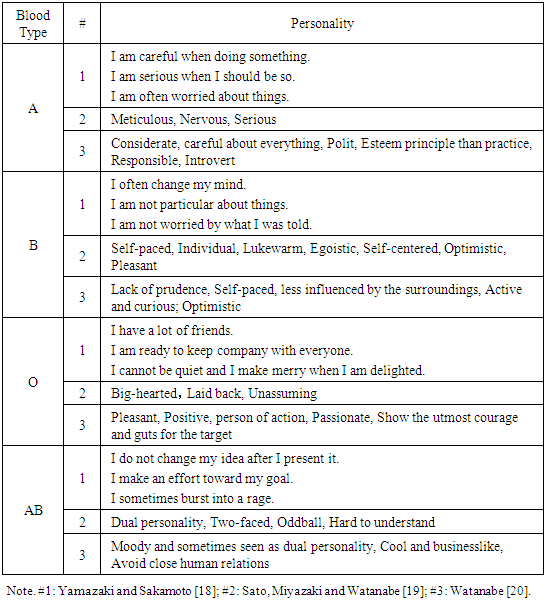

- Questionnaires by Japanese psychologists reported the following images of each blood type. Yamazaki and Sakamoto conducted a survey of 177 female undergraduate students on 24 personality traits in the annual opinion poll by JNN Data Bank, a department of Tokyo Broadcasting Corporation, one of the major television networks in Japan [18]. Sato, Miyazaki and Watanabe surveyed 197 undergraduate students and the results of free responses [19]. Watanabe extracted personality traits of each blood type from multiple books and asked 102 undergraduate students whether they were applicable [20]. These results are shown in Table 2. In general, the personality traits studied by Japanese psychologists were consistent with those of Nomi (Table 1).

|

1.4. Results of Personality Tests

- Questionnaire-based personality assessments are frequently used in psychology and consist of answering multiple questions regarding self-reported personality traits; responses are then integrated into several personality factors by statistical processing. In theory, this means that the self-reported answer will either directly or indirectly appear in the result. Although there are many academic studies on the relationship between blood type and personality, the inconsistency among results [7-9,12,20-32] has led to an endless academic controversy about whether the relationship has been scientifically confirmed. Many studies examined the association between blood type and personality using the “Big Five” personality test, which has been extensively present in contemporary psychology. However, none of these results has been consistently replicated [9,12,22-24,30-32].The Big Five personality test, as the name implies, comprehensively describes personality using five factors called the Big Five [33-34]. The model collects vocabularies from dictionaries and traditional personality tests, as well as re-analyses of personality scales, and the five factors were extracted through factor analysis. Thus, the Big Five does not assume any background theory; it is characterized by the bottom-up process and personality is comprehensively captured by the five factors [35]. These five factors are usually called Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. The NEO-PI-R, commonly used as a Big Five personality test, consists of 240 question items, each of which is rated using a five-point scale [36].

1.5. Self-fulfilling Prophecy

- The term “self-fulfilling prophecy” refers to the phenomenon in which a person who believes in a prophecy learns to act in accordance with the prophecy, thereby bringing the prophecy to being. An example that psychologists have studied is astrology [37-39]. If a person's original personality matches his/her astrological sign, that tendency becomes stronger. Even if the personality and the sign do not initially match, the personality moves toward what has been predicted by the astrological sign.In Japan, Korea and Taiwan, roughly half of the people believe the relationship between blood type and personality is legitimate [10,12,16-17,22,40-42]. Logically, the self-fulfilling findings among astrology suggest that one's personality would change in a direction that conforms to the descriptions suggested by his/her blood type. Based on this self-fulfilling prophecy hypothesis, several large-scale surveys in Japan using the items in Table 2, designed or analyzed by academic researchers since 1990, clearly confirms this phenomenon. Archetypical sample sizes of these were 1,300 [41], 6,660 [42], 11,766 [43], 32,347 [18,44-45], and over 200,000 (our estimation; the exact number was not specified in this report, although it alluded that the size was much larger than preceding surveys) [46]. Nevertheless, researchers have confirmed no coherent statistical difference in participants without knowledge of astrology or blood type [40-46]. In other words, the current scientific consensus is that these differences are self-fulfilling phenomena induced by the “contamination by knowledge” [9,18,22,27,37-46]. However, there was little testing of whether the questions used in these studies were suitable for examining differences among less knowledgeable respondents.

1.6. Contemporary Trends and Issues

- After 2000, a growing number of studies proved the previously questioned link between blood type and physical constitution, with the exception being in the weak gastrointestinal tract: this demonstration proposed a new approach to medicine [47-48]. For example, several studies found that individuals with type A were more susceptible to COVID-19, whereas individuals with type O were less susceptible [49-51]. There have also been several studies on biological factors, which investigated whether physical constitution affected personality. An American researcher evaluated the both the ABO genotype and its phenotype, and the linkage of disequilibrium between the ABO and DBH genes [52-53]. A Korean 2011 EEG analysis study rated type O as having higher scores in awareness and stress resistance than other types [54].In 2015, a Japanese study using DNA testing methods found that ABO genes of 1,427 participants tended to be persistent in type A, as predicted by blood type personality theory [55]. This study used the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) which built a model for temperament with a physiological basis in the background, unlike the Big Five. The TCI, a top-down personality model, is often used to examine genetic dispositions [56-57]. The test consists of 240 items using a yes-no scale rating. Cloninger hypothesized that personality consists of traits that are hereditary and stable throughout life. The TCI consists of seven dimensions, including 4 temperament dimensions (Novelty Seeking, Harm Avoidance, Reward Dependence, and Persistence) and 3 character dimensions (Self-directedness, Cooperativeness and Self-transcendence). Three of the temperament dimensions have been hypothesized to be associated with monoamine neurotransmitters. Novelty seeking has been hypothesized to be associated with dopaminergic, harm avoidance with serotonergic, and reward dependence with noradrenergic.With the progress of information technology, conducting crowdsourced surveys has become much easier. Therefore, a larger amount of data can be obtained at a lower cost and in a shorter period. Most Japanese people know their blood type since, until recently, it had been common practice to test the blood type of newborns. This means that analyzing the effect of the phenotype eliminates physiological type testing, and therefore our survey can be completed via the Internet.

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Participants

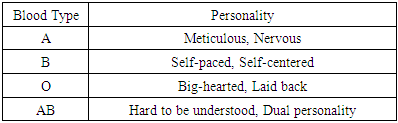

- The data used in this study was collected by the means of crowdsourcing. The survey was conducted in 2020 with a sample size of 4,000 Japanese individuals between the ages of 20 and 59. The participants were asked to rate a total of 8 items representing 4 blood type (A, B, O, AB) traits, each with scores from 1 to 7 for their own personality traits (the larger the number, the more fitting the trait). Respondents were also asked which blood type they thought these 8 items would correspond to. Additionally, scores of 1 to 3 denoting the strength of the relationship (the larger the number, the closer the relationship) and 1 to 4 of their own familiarity with blood type personality theory (the larger the number, the more knowledgeable the participant was).We tried to follow those methods of psychological personality testing, and deliberately selected the most suitable traits (Table 3) that would certainly produce the differences: images of traits were consistent to the preceding academic studies, they showed large differences in the academic studies and their means were close to 50%, they did not show extreme values, and they were consistent to the preceding surveys of other studies.

|

2.2. Statistical Analysis

- We focused our analysis on whether personality self-fulfillment was occurring or not, using data from participants who “have no knowledge of blood type personality” or “do not believe in the relationship” (hereinafter abbreviated as “no-knowledge group”). This survey had 1,474 participants from the “no-knowledge group”; we believed these participants would be free of the aforementioned “contamination by knowledge.”Our analytical methods were as follows:Analysis 1: ANOVA of blood type and personality of the whole participantsAnalysis 2: ANOVA of blood type and personality of the “no-knowledge” groupWe set the alpha level to 0.05. ANOVA were used to analyze blood type traits. The distributions of participants’ blood types were almost equal to the Japanese average.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis 1: ANOVA of Blood Type and Personality of the Whole Participants

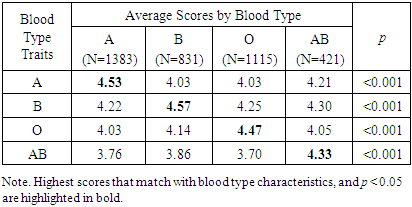

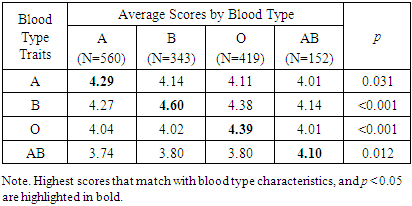

- All traits showed the same results as those shown for blood type traits in the preceding psychology studies (Table 2). All traits were statistically significant at p < 0.05 (Table 4). All the responses were consistent with the most common images of blood types that respondents expected.

|

3.2. Analysis 2: ANOVA of Blood Type and Personality of the “No-knowledge” Group

- All traits showed the same results as those shown for blood type traits in the preceding psychology studies (Table 2). All traits were statistically significant at p < 0.05 (Table 5).

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Issues with Personality Tests

- In this study, all blood type trait items clearly showed the differences as predicted. This study measured self-reported personality traits, and since many Japanese believe in the relationship between blood type and personality, conventional personality psychology theory suggests the differences among the blood types will certainly appear, as previously mentioned. For the same reason, personality psychology is not sufficient to explain the inconsistent results that have appeared in previous research [7-9,12,20-32].Ryu and Sohn [58] re-analyzed Cho, Suh and Ro’s result of the Big Five test of 40 items [22], and found statistically significant differences which match with blood type traits in 10 individual items. This means that in the case of a “personality factor” composed of multiple items, the difference by the blood type decreases ‒ few significant differences appear. Thus, the Big Five personality test can hardly detect minor differences in personality, such as those that may be caused by a single gene, at least theoretically.If the relationship between ABO blood type and personality exists, respondents are expected to exhibit the personality traits corresponding to their own blood type more strongly than the other types. And if these differences are inborn, not due to the self-fulfilling phenomena induced by the “contamination by knowledge,” it is also expected that the same differences in scores will be found in the groups with no knowledge on blood type traits. Thus, the lack of statistical significance in previous studies could have been a Type 2 error caused by the small sample size, multiple-item measures, or unsuitable questions.

5. Conclusions

- Both all blood type traits in the whole participants and all traits in the “no-knowledge group” clearly showed the differences as predicted. We found a clear relationship between blood type and the self-reported personality using 8 single question items, which matches traits previously stated.Meanwhile, the sample in this study was limited to Japanese populations. Additional research using a large, more global dataset is needed in order to address the true implications as well as to improve methodologies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author is grateful to Chieko Ichikawa, Director of the Human Sciences ABO Center, for her support. The author also thanks Professor Qinglai Meng of Oregon State University, as well as Fred Wong, co-founder of AI Hong Kong Limited, for their kind comments and suggestions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML