-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2020; 10(4): 100-108

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20201004.03

Received: Sep. 1, 2020; Accepted: Oct. 15, 2020; Published: Oct. 30, 2020

Psychological Resilience and Poor Communities Coping with COVID-19 Pandemic

Mohamed Buheji

International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain

Correspondence to: Mohamed Buheji, International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Any community resilience and total recovery from a devastating international health emergency, as COVID-19 pandemic, cannot be complete without ensuring that the negative spillovers are eliminated or mitigated from all social classes, especially the lower middle class and the poor. Since the 1960's of the earlier century, many studies have focused on what and how people move in and out of poverty, however, few have gone in-depth of when people go into poverty and why they to that stage. In this paper, the author attempts to take a reflective approach about how people may go into the trap of poverty, or deepen their status into it without having the psychological resilience. With the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic, the world is expected to lower middle class, and more people would be deeply living in absolute poverty that would come back to many areas in the world, Buheji (2019c). Therefore, finding proper frameworks that would mitigates the expected psychological scare and emotional pain is highly important. The implication here is that the framework is very pragmatic and need to be disseminated to the poor communities through all the recovery projects.

Keywords: COVID-19 Pandemic, Psychological Resilience, Coping, Poor Community, Poverty, Resilience Economy

Cite this paper: Mohamed Buheji, Psychological Resilience and Poor Communities Coping with COVID-19 Pandemic, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 10 No. 4, 2020, pp. 100-108. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20201004.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The need to re-invent how the world could develop the poor community during times of uncertainties have not been covered enough in literature. This subject is more important than ever, as the world is expected to go through more periods of uncertainties in the next coming era’s. Each major change in the conditions of the poor community environment affects their mental health and their capacity to come out of poverty. Buheji (2019a), Ayllon (2015).With the shakeup of the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic and its expected spillovers, as the repeated lockdowns, major adversity or mental health trauma's are going to affect the lives of the underprivileged, Sanders et al. (2008). Many have already experienced emotional pain and stress. These negative factors require more resilient individuals and communities that have a resilient mindset, developed attitudes and behaviours. Such resilience needs both time and intentionality which help in building ‘psychological resilience’ program with the poor communities. Buheji (2020).In this paper, the challenges of the poor communities during lockdowns are identified. Then the psychological resilience for the poor community during and after COVID-19 are re-defined along with the requirements are specified. Based on the review of the types, the characteristics and the mechanisms of psychological resilience, a ‘problem-focused coping strategy’ is suggested for mitigating the poor people wellbeing. Buheji et al. (2020b), Boyden and Cooper (2007).Factors sustaining poor communities' psychological resilience are further explored in relevance to their opposing barriers. The author reviews the role of the mindset towards optimising the underprivileged communities assets and how to enhance their preparedness. Buheji (2020).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Challenges of Low-Income and Poor Communities During COVID-19 Lockdowns

- One effect of the lockdown on the poor and low-income families, specifically those living in the urban areas is that it would have a more difficult time to make their daily income, Sanders (2008), Orthner et al. (2004). The lack income means lack of availability of material resources that impacts the ability of the family to survive and thus would delay any efforts for developing new beliefs that would support positive behaviours and self-efficacy that lead to working for independent wellbeing. Mullin and Arce (2008). Low-income household economic situation, besides their low capacity for problem-solving, communication, utilisation of their social or natural asset or accessibility for on-time social support prevent them from having much tolerance. Buheji (2018b), Orthner et al. (2004).In countries where the poor and low-income families constitute more than half of the household population, as in the Philippines, several stressors come from either psychosocial, or physical environment, Mullin and Arce (2008), Orthner et al. (2004). Engaging the poor in programs that would help the poor community work on projects that affect their life as finding solutions to the inadequate sanitation and the drainage, or the limited access to clean water, overcrowding, and other threats to physical health, Buheji (2018a) and Jacson (2016).

2.2. Defining Psychological Resilience

- Resilience as a physical phenomenon means the ability of a substance or an object to spring back into shape, specifically after being pulled, or stretched, or bent due specific intention or condition. Resilience is a process that can be achieved through protective factors that are derived from people and the resources around them. Buheji (2019c).When defined on people and communities, resilience can be about the ability to absorb or bounce back from specific strains or challenge, Buheji (2020). At the same time, psychology resilience can be defined as the process of adapting well in the face of challenges, crisis, threats, and tragedies. It is about the capacity of an individual, or group, or a community to achieve safe, or positive outcomes despite risks or adversity. Boyden and Cooper (2007).Phycological resilience comes in many forms which all reflect the mental capacity and the behaviours in managing the negative effects of stressors. Resilience exists when tolerance during crises/chaos can help to mitigate the incidence without long-term negative consequences. The capacity to positively adapt an unprecedented challenge, similar to the COVID-19 pandemic is another definition of resilience. Hence, resilience is beyond being a trait; it is more of a process. Buheji (2019b).Resilience can be seen when people adapt and cope with a challenge while springing back to spillovers of the crisis. Resilience is the preventive remedy for the accumulated feeling of denial, or resentment to the reality of the challenge or the crisis, Levine (2015). Unless this resilient fully psychologically activated, it would lead to devasting results that would increase the anxiety. Boyden and Cooper (2007).

2.3. Importance of Psychological Resilience to Poor Communities

- Resilience brings in self-confidence while also being balanced in ego-control related to behavioural adaptation. Demographic information from different studies shows that women have less capacity for adaptation for disasters than men, i.e. they have less likelihood of psychological resilience. Buheji (2019b).In military studies, it has been found that resilience is also dependent on group support: unit cohesion and morale is the best predictor of combat resiliency within a unit or organisation. Resilience is highly correlated to peer support and group cohesion. Units with high cohesion tend to experience a lower rate of psychological breakdowns than units with low cohesion and morale. High cohesion and morale enhance adaptive stress reactions. Dealing with difficult adverse events creates a painful experience that might have detrimental effects on the outcome of the life journey of a total poor community. Thus, unless the conditions are controlled, or modified, or absorbed by first acceptance and seeing the alternative opportunities with an abundant mindset, the crisis would create negative spillovers on individuals and the community mental health and their capacity to tolerate the difficult circumstances and certainly would reduce their probability to get out of this vicious cycle. Buheji (2019b).An important feature of psychological resilience in overcoming the negative effects of adverse conditions on an individual's or a community's functioning requires promoting resilience and cohesion among parents living in poor, or low-income neighbourhoods while focusing on specific values and behaviours, Buheji (2020). Jacson (2016) sees that such poverty-focused efforts would influence the poor families parents' psychological wellbeing. Wilson-Simmons et al. (2017).One of the primary requirements for psychological resilience is the ability to mentally and emotionally cope with a crisis, especially when it more of a sudden crisis, or when it is beyond what is expected. The other requirement would usually focus on the capacity to bounce back and develop from the status of the crisis, or to return to pre-crisis status with high availability.

2.4. Characteristics and Mechanism of Psychological Resilience

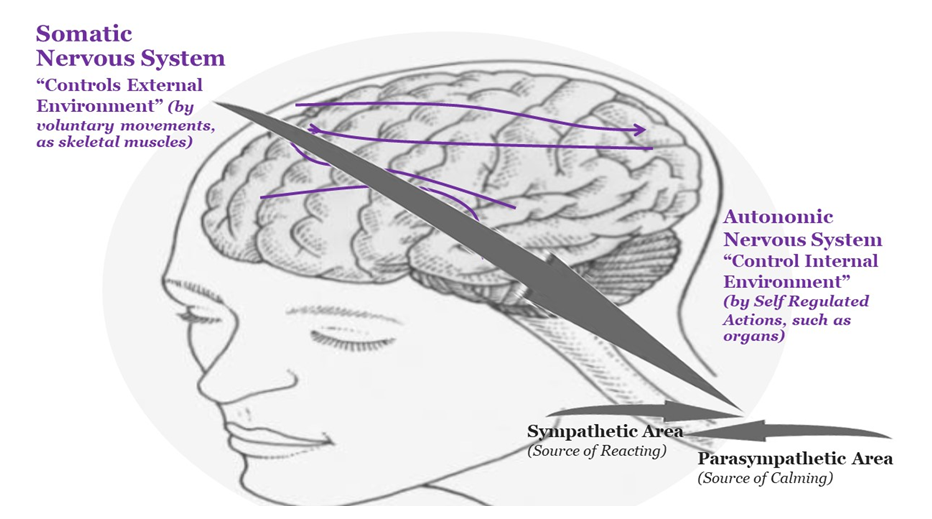

- There are three characteristics for psychological resilience: self-confidence, self-esteem and self-concept. These characteristics influence both the central nervous system and the somatic and autonomic control systems of the peripheral nervous system. Specifically, the autonomic system, plays an important role in psychological resilience as it controls both the sympathetic and parasympathetic areas in the nervous system, which lead to navigating between arousing and calming during any challenge or crisis, as illustrated in Figure (1).

| Figure (1). Illustration for the Sources of Psychological Resilience in the Brain and the Nervous System |

2.5. Challenges of COVID-19 Spillovers and Type Psychological Resilience

2.5.1. Dealing with the Pandemic Spillovers

- The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it many spillovers which disrupted many families and communities life balance. Some of these spillovers presented new sources of opportunities that could enhance the tolerance of the targeted communities if well utilised, Buheji and Ahmed (2020b). The pandemic spillovers might lead to community instability, especially if this instability increased with the limitation of access to water and electricity, or when there are challenges in accessing food. Buheji (2020).Resilience is negatively correlated with neuroticism and negative emotionality personality traits. These traits are most potential when COVID-19 pandemic stays threatening, problematic, and distressing, and to view oneself as vulnerable. The poor usually misses the proper orientation with their socioemotional factors, and this eliminates the possibility for positive emotions that help to establish enough resilience during stressful times. Therefore, we need to build more engagement projects that help the poor to raise the socioemotional factors that lead them to benefit-finding and cognitive reappraisal during challenging times, Buheji (2018a). This would create a cognitive reappraisal that would help the poor maintain optimism, and goal-directed problem-focused coping.

2.5.2. Overcoming Active Inertia

- Many see resilience as the only solution to raise the capacity of coming out of a deeply stressful situation. However, resilience should cover the avoidance of repeating the same mistakes through the concept of active inertia. With the learning from the active inertia, the poor communities should be selective in taking the appropriate actions that would enhance psychological resilience at the right time.If the poor community manages to overcome the active inertia, then they would stop establishing patterns of rigid behaviours in response to their routines or challenges. Active inertia happens when the poor community are faced with an adverse event, and they react the same way, i.e. either they would have negative emotions, or become unable to react. Buheji (2020).

2.6. Problem-focused Coping for Poor People Wellbeing

- Coping is a behavioural technique suitable for confronting a stressful situation and dealing with it through being either: task-oriented, or emotion-oriented. In this paper, we focus on task-oriented coping since it is the source of problem-solving based coping. Buheji and Ahmed (2020a), Billings and Moos (1981).Problem-focused approaches help the poor community to build new methods for coping, which strengthen their resistance to stress and thus lead to the allocation of more sources of positive emotional resources. The new methods of coping found to be very relevant to the wellbeing of the poor community. Thus, we need to supply such a community with more capacity to interact with their environment, Buheji (2019b). Using problem-focused coping approaches help the poor community and the processes that either promote their wellbeing, or protect them against the overwhelming influence of risk factors. When a level of resilience is available, we could experience a pattern to cope with the different communities challenges. Coping help the poor community to not to play the victim role when responding to a situation, Nurius et al. (2020). When the poor avoid negative coping habits by getting engaged in their psychological resilience, we would not see the act of avoidance, and would even control the negative coping habit of excessive increase in: smoking, alcohol drinking, suicide attempts, run away, all day sleeping, etc. The emphasis of positive problem-focused coping would constrain the negative emotions to involve fear, anger, anxiety, distress, helplessness, and hopelessness which decrease a person's ability to solve the problems they face and weaken a person's resiliency. Buheji et al. (2020b), Billings and Moos (1981).

2.7. Role of Phycological Resilience Mindset during COVID-19

2.7.1. Role of the Mindset

- A psychologically resilient mindset can enhance the immune system functioning and specifically in increasing levels of an antibody salivary immunoglobulin A, which serves as the first line of defence in respiratory illnesses. Studies show that psychological resilience helps in the faster recovery rate and management of pain which lead to lower readmission rates to hospitals for the elderly, and reductions in a patient's stay in the hospital, among many other benefits. During COVID-19 pandemic, it is important for the poor community to maintain positive attitudes towards the accumulating challenges through experimenting and by learning with high flexibility and adaptability. As per behavioural science and behavioural economics, mentioned in Buheji, and Ahmed (2020a), building resilience needs a mindset that manages the positive behaviours and thinking patterns. With proper life-purposefulness, the mindset would enhance the self-monologue, which increases our belief on specific life and livelihood values. This well-framed mindset enhances tolerance and makes us focused on specific goals in life that would eliminate negative self-talk. Both the integration of focused mindset, and self-monologue help on mitigating the psychological-stress, when faced with sudden, or series of challenges. Thus, we would not hear "I can't do this" and "I can't handle this", but instead can selectively focus on "what can happen from me", or "what I can do" and "I can handle this". Psychological resources include the cognitive processes, that allow us to self-regulate and manage ourselves in response to a changing environment as well as our personal beliefs and attitudes about ourselves and our situations. While our genetic inheritance certainly makes a contribution to the personal psychological resource we enjoy, lack of material resource has an impact on our ability to develop and strengthen these resources. Crockett (2019).The Besht model of natural resilience-building emphasis that families should start as early as possible in emphasising realistic upbringing that is supported by an effective communication model, Mullin and Arce (2008). This help to have a mindset that has the capacity for positively restructuring the demanding situations and then gradually accumulating better self-realisation and hardiness with the new challenge. Levine (2015).

2.7.2. Role of Optimisation of Assets on Resilience of Mindset

- Crockett (2019) sees poverty is about the lack of non-material resources rather materialistic resources. The issue of poverty and its persistence stems from the absence of resources which lead to financial resources, understanding this point would adversely change the circumstances of the poor effectively, Buheji and Ahmed (2019). These include social resources such as education and social and community networks but also include less obvious, psychological resources. Ayllon (2015).From the experience of more than 300 projects since 2015, under the international inspiration economy project (IIEP) many poor live in abundant and rich natural and physical assets areas which can re-invent their level of income and livelihood. Assets include land, buildings, livestock, machinery, liquid assets and other forms of physical capital. Buheji (2018a) mentioned that poor communities that managed to re-invent the way they manage their different non-financial assets over time through savings and other means are effectively improving their future prospects while increasing their resilience to weather-related and other shocks. In certain circumstances the poor families choose to sell off their assets in order to maintain consumption and keep the family fed, but at the cost of next year's opportunities, prolonging hardship. Choosing instead to protect assets by reducing consumption might preserve a family's opportunity but at the cost of the family's health and physical abilities and even their children's growth and development, Buheji and Ahmed (2020b). Buckner et al. (2003) advised that this could be differentiated by building resilient youth that would have the capacity to have self- and emotional-regulation skills.

2.7.3. Mindset Preparedness for more Challenges

- Buheji and Buheji (2020) emphasised that in order to be fit for the coming era, every individual need to be prepared for challenges, crises, and emergencies by creating emergency response plans, business continuity plans, and contingency plans, including the alternative plans for worse financial or socio-economic crises. This means we need to review all the types of assets the poor community has, and then try to fill the gaps as per the type of asset most needed. The narrowing of the gap would help to develop a robust emergency response plan that would enhance the coping effectiveness and make the poor community remains functional. Buheji (2019a).The American Psychological Association (APA) suggests that in order to maintain a well-balanced psychological resilience we need to: maintain good social relations, especially with close family members or friends, accept early the crises but work also early to mitigate their spillovers, see problems as opportunities for new pathway in life, and accept circumstances that cannot be changed. Buheji and Ahmed (2020b), APA (2012).

2.8. Factors for Enhancing Psychological Resilience

2.8.1. Enhancing the Capacities of Resilience of the Poor in Post-COVID-19

- The challenges of post-COVID-19 emphasis that the NGOs and poverty elimination organisations should focus on developing both physical and mental health capacities of the poor, Buheji and Ahmed (2019). This can be done only through establishing mindsets that are with assumptions, behaviours, and attitudes that appreciates the different assets with the community. Carter et al. (2018).The studies of Buheji (2018a) found that the life of the poor can be re-invented once they are engaged in projects that could alter the way they see their role in life. This is specifically unique experience once the poor community work on both optimising the utilisation of their different abundant assets and ensure access of their children to educational services.Recent studies have shown that stress, depression or a deterioration in physical health can affect cognitive function, resulting in hardship that reinforces stress and depression. This kind of self-reinforcing loop—a behavioural poverty trap—means that the experience of poverty itself can influence an individual's future decisions about productivity. Ayllon (2015).Russell (2018) reported the high possibility of 'behavioural poverty trap' raise the psychological distress and lead to fewer attempts to establish new socio-economic resilient practices.

2.8.2. Enhance the Resilience Capacity of the Poor through Self-Sufficiency Projects

- Carter et al. (2018) one of the main risks on the poor communities that coincides with health risks are the environmental risks that come in the shape of drought, or flood which intensify the extent of losing sources of daily income and increase of minimum living costs due to market instability. The more there are a variety of risks, the more there would a larger impact on the poor family and the extent of shock they would live through. This status of shock discourages NGO's from investing in productivity-related projects.One of the interventions that proven to be most effective in enhancing the resilience of the poor community during both health and environmental crisis is agricultural self-sufficiency projects. The poor families should be trained to increase their income in good times which use their products as a safety net in bad emergency times. However, the community should follow a holistic approach where different families would be planting items for sales like cotton and sesame, which are both high-value cash crops while other parts of the community would be raising livestock which would ensure sustenance of food source. Buheji (2018a).

2.8.3. Factors Sustaining Psychological Resilience

- There are factors that help to sustain a psychological resilience, these factors are reflected through confidence, communication, commitment towards overcoming a challenge or towards problem-solving, and the last but no least extending the capacity to manage strong impulses and feelings. These factors require the individual to be self-disciplined, self-directed, self-conscious. These factors can increase it is mixed with the belief of a life goal, or belief of one role towards religion, or when self-fulfilled with spirituality, or mindfulness. The factors for sustaining resilience work like regulators and control emotions, in order to enhance resilience, which regulates negative emotions that lead to stress and other sources of mental illness.Studies show that psychological disorders can be avoided by psychological resilience which can help resume life. Defined as adapting to changes caused by stressful events in a flexible way and recovering from negative emotional experiences, psychological resilience impacts on the illness process and the subsequent health. (Polizzi et al., 2020).Polizzi et al. (2020) emphasised that more efforts are needed for mitigating the impact of the economic hardship, fears of contracting the lethal illness and the consistent feelings of hopelessness. Without constructive psychological resilience programs, especially with the under-privileged, we would see a huge spike in posttraumatic stresses. Referring to research on how people have coped with specific life challenges would help the knowledge community foresight through comparative analysis how to set up or identify most suitable strategies for managing the accumulated distress of the poor, specifically in challenging times, to help avoid fill in the trap of vicious cycle of poverty. Buheji and Ahmed (2019).Carter et al. (2018) seen that to sustain escaping from poverty and to achieve resilience we need to innovate in ways that would increase the dynamics of assets, enhancement of the poor families capacities and reduction of risk on them.

2.9. Protect the Coming Generations of Poor Families through Psychological Resilience

- Living in poverty, during a devastating international emergency, places many poor children at an increased psychological risk that might lead to negative behavioural, cognitive, and health outcomes, Pettit (2016). Family members play a huge role in fostering poor communities' resilience to provide healthy human development. If the family promote the spirit of resilience within its members with a frequent display of warmth, affection, emotional support, supported by the maintenance of family gathering the poor community would feel secure and confident. Pettit (2016).Family resilience can create a stable equilibrium which is conducive to balance, harmony, and recovery. Exploiting family resilience during difficult times help to must learn to reorganise the relationships with the family and change the patterns of functioning with it by adopting new habits that mitigate long-term negative consequences. Shumba (2010) showed that despite that poverty has a negative impact on school success and the social and emotional functioning of learners in schools, if the student manages a personal belief about their capabilities, they would have intrinsic driven motivation and would become notably resilient and adaptive.

2.10. Mitigation of COVID-19 Psychological Spillovers on Poor Communities

2.10.1. Optimising Positive Beliefs

- With the second wave of COVID-19 the international organisation as UN, WHO, etc., need to do thorough exploratory studies and semi-structured interviews with the poor community and their families. The mitigation towards psychological resilience in the poor community should help to build to optimise the positive beliefs, and in taking action steps towards establishing resilient poor families, that reflect more dynamic positive family beliefs that are inter-dependent from social support programs. Mullin and Arce (2008), Crockett (2019).Nurius et al. (2020) seen that victimisation of the poor, for example, due to racial and ethnic minority, enhanced the prevalence of poverty and lowered their resilience capacities. The victimised poor suffer three mental health signs—depression, suicidality, and broader psychological wellbeing. Nurius et al. (2020).The poor community need a type of secure income through the periodical purchase of services, which should be guaranteed by the government, which would be in alternative would provide more accessibility for educational and healthcare accessibility. The social workers of the social development departments in the government should continuously evaluate the impact of the support services on poor families behaviour and decision making.

2.10.2. Empathetically Realising the Socio-economic Conditions of the Poor

- One of the most important behaviours is the practice of empathy. When we become empathetic about the elderly, we prepare the path for ourselves once we become as in their age. Empathy facilitates the deep realisation of the influence of the crisis on the poor community, Levine (2015). Thus, once we have this empathetic feeling, we appreciate the depth of stressors and what type of adaptation needed. Once we understand the stressors, we can establish proactive protective factors that properly establish psychological resilience. Fostering resilience for people living in poverty could start with selective creative solutions that reduce the negative cognitive impact on the poor by mitigating the risks of their socio-economic conditions, Buheji (2019a). EHDI reports that the risk of non-resilient poverty can lead to further poor social, emotional, behavioural, and educational outcomes. Poverty found to affect the neurobiological capacity and the impacts brain development as well. In order to mitigate this risk, EHDI encourages early intervention that would help develop the power to spark change and chip away at the overwhelming circumstances of poverty. EHDI (2015).

3. Methodology

- In this paper, we establish a methodology that identifies the type of coping strategy through the engagement of the poor in self-sufficiency projects which would help to open the mindset of the community to the possibilities rather the limitations of their assets and power. The applied cases here are from the experience of the International Inspiration Economy Project (IIEP) which started since 2015 and is working today in 21 countries to solve socio-economic problems with more focus on the poor communities. The projects taken as an example are meant to illustrate the new meaning for engagement, and how to build distress tolerance that would foster deeper human interconnectedness, Buheji et al. (2020a), Buheji (2018a).The behavioural activation in the case study target to make an analogy of what makes psychological resilience for long-term accumulated exposure of a deadly disease as the COVID-19. The engagement in projects targets to raise the mindfulness and decrease stress coming from the pandemic and similar expected international and national emergencies.

4. Case Application

4.1. Introduction

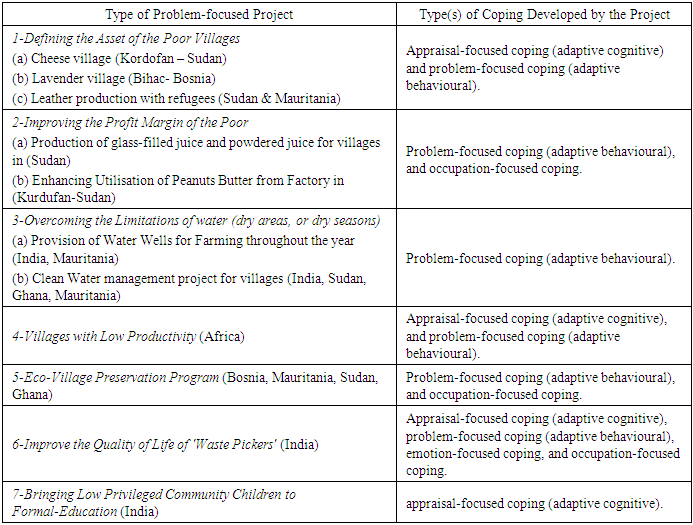

- The case study shows the types of coping strategies for each poor community socio-economic problem. These different problem-focused projects target to help protect, or positively influence the psychological resilience of the poor. Only selective projects were taken to give an example, due to the limitation and the scope of this.In this case study, we would specify the type of coping for the projects listed. The type of coping was selected from the work of Billings and Moos (1981) and which include: appraisal-focused coping (adaptive cognitive), problem-focused coping (adaptive behavioural), emotion-focused coping, and occupation-focused coping.

4.2. Problem-focused Coping for Poor People Wellbeing

- Problem-focused coping can be integrated in the projects with the poor. The project can prepare, or enhance the wellbeing of the poor through engaging them in overcoming the different challenging life and livelihood situations created by the pandemic of COVID-19. In this case study, we extract the experience of five years for IIEP projects towards poverty elimination. The goal of every IIEP project is to help the poor establish more connectiveness with their potential assets which could help them to withstand and learn from the difficult and traumatic experiences while remembering their capacities, even during challenging times. Buheji and Ahmed (2019), Buheji (2018a).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- The COVID-19 pandemic, which became a public health crisis, created effects, and concerns on the life and livelihood and which accumulated lots of negative impact on the poor community that could negatively affect their psychological resilience. However, COVID-19 pandemic also brought with it more opportunities which provide possible choices for more projects in poor communities. The length and the spillovers pandemic brought panic, depression, anger, and confusion to many poor communities. Depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder are the most common psychological disorders among the poor community. With the advent of COVID-19 pandemic, the worries of this disorder are highly increasing. This paper presented resilience from the engagement in problem solving perspectives. The aim here is to show how this would reduce the emotional distress of the poor through engaging them and their community in projects that enhance their coping mechanism. With the complexity of COVID-19 spillover, poverty is expected to increase and one of the main solutions to mitigate the depth of this problem in the different communities is to enhance the psychological resilience of the poor. The author shows through the case study an analogy of the psychological resilience that could be achieved through the engagement of the poor in realising their opportunities, instead of waiting for extrinsic resources. The outcome of this analogy shows that the poor should have the capacity to withstand hardship during challenging times, if they engaged in projects that would lead to their psychological resilience. In reality, the poor need to be equipped with a coping mechanism that makes them more prepared in mitigating the effects of the pandemic negative influences, or in exploiting the alternatives that this pandemic brings with it. The paper conclude that coping mechanisms if well-approached could help the poor to manage the increase of lockdown and social isolation through more projects that would mitigate possibilities for inequalities, or discrimination, or any other spillovers that would make the poor even more vulnerable, or trapped in the vicious cycle of poverty. Despite the limitations of this paper of not being tested deeply in the poor communities in during the COVID-19, this work focused on building more effective and sustainable coping strategies through projects engagement. This project engagement could prevent many poor communities from being exposed to numerous hardships, specially with a devastating pandemic. The psychological resilience built through engagement with civil society projects would change the consequences of the pandemic negative spillovers. The implication of this study is that it helps to bring more framework that could lead to both positive hope and emotions, besides effective coping mechanism. The other implication is that this proposed mechanism and framework is another step towards closing an increasing gap that the pandemic created and would address the top essential point of the UN sustainable development goals (UN-SDGs). Yes, we can do it.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML