-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2020; 10(3): 76-83

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20201003.03

Intelligent Living with ‘Ageing Parents’ During COVID-19 Pandemic

Mohamed Buheji 1, Amna Buheji 2

1Founder, International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain

2Medical College, Arabian Gulf University, Bahrain

Correspondence to: Mohamed Buheji , Founder, International Inspiration Economy Project, Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper brings three variables together living with ‘ageing parents’, especially those suffering from chronic diseases or dementia, during the COVID-19. The researchers investigate the effects of these three variables on multi-generational living, the quality of life and in preparation of the new normal. The way of most of life and lifestyle business-model for each ‘ageing parent’ are evaluated with the intention to build the most suitable model that improve their wellness, functionality and quality of life during this part of life. A framework would be proposed to minimise any lost opportunity and enhance the capacity of creating the most intelligent decisions during these unprecedented times.

Keywords: Ageing Parents, Multi-generational Living, Lost Opportunity, COVID-19 Pandemic, Quality of Life, Wellness

Cite this paper: Mohamed Buheji , Amna Buheji , Intelligent Living with ‘Ageing Parents’ During COVID-19 Pandemic, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 10 No. 3, 2020, pp. 76-83. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20201003.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is natural that the adult children love their ‘ageing parents’ and want to ensure that they get the proper care; especially when their parents or the conditions around them become not stable. These worries have increased by many folds since the early of 2020 with the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Berman (2016).Living with ‘elderly parents’ means we need to be prepared to live a fuzziness situation till we realise what type of help they really need or require, without undermining their right of choice, when they can. When we decide to live with an ‘elderly parent’, whether due to their sudden needs, or due to living as part of an extended-family we need to understand that we are more accountable for their quality of life, i.e. have the authority and responsibility to explore what suites them most to have a span of choices so that they have the ability to experience these choices. Berman (2016).COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and social distancing have emphasised on many of us to adopt empathetic thinking of how we should care and support our ‘ageing parents’, Flegar et al. (2020). This empathetic thinking would make most of us keen on ensuring transferring the proper knowledge with our ‘ageing parents’. Bhanoo (2020).The paper emphasises the importance of having a framework that addresses many queries and dilemmas when living with different types of ‘ageing parents’. Some of these parents might be totally independent, while others might exhibit troublesome dementia-related behaviours. The proposed framework helps to play like an intelligent system that optimises the most effective care for the ‘ageing parent’ and create for them a sense of stability in unstable times. Butcher et al. (2001).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Living with Ageing Parents

- According to the Caregiving in the U.S. 2020 research report published by the National Alliance (2020) for Caregiving, 40 per cent of family caregivers report that their care recipients live with them. Many people, all over the world, promise their parents that they would never place them in a long-term care facility, the authors claim to be one of them and pride themselves about this choice. However, this requires many obligations. Creating stability for our ‘ageing parents’ in unstable time requires caring for their physical and mental health, through creating a well-defined boundary that ensures intense caregiving situation. Bhanoo (2020).COVID-19 pandemic created confusion and led to anxiety to many elderlies and created for them a feeling of fuzziness. This raised their need for assistance. Therefore, today many adult children find themselves in a delicate situation about what to do and how to do in relevance to their ‘ageing parent’ life and livelihood. These questions open many worries that often lead to what-if scenarios. Flegar et al. (2020).

2.2. Understanding What Type of Help Our ‘Ageing Parents’ Need

- Many challenges in life are so small when compared to the dilemma and worries of giving proper and suitable care to a one's old mother, or ‘ageing parents’ (i.e. Beyond 70 years old).While being worried about our ‘ageing parents’, sometimes you would be questioning whether ‘assisted living’ be a better option? Sometimes you would question whether the elderly parents would be comfortable in living in the same house with other people with different generations and where they would not be controlled in the house. With ‘Ageing Parents’ starting to live cognitive limitations, functional mobility impairment; technology is used more to help decrease their loneliness. However, in different communities, technology has increased the isolation of ‘ageing parents’. Therefore, deploying online technologies into use could solve long-term physical and mental problems. Recently published evidence has shown that online-based therapy has aided in reducing the feeling of loneliness, depression and anxiety. Chatterejee and Yatnatti (2020), Käll et al. (2019), Pinquart and Sorensen (2010).

2.3. Benefits of the Extended-Family in Caring for Elderly

- Regardless of who moves in with whom, the decision to live with ‘ageing parents’ is a serious choice that affects all relationships within a family. This decision affect life and livelihood growth and development, besides it affects careers, finances, and the physical and mental health of everyone involved. Arbaje (2020).The benefits of living in an extended family with multiple generations can reflect positively upon the ‘ageing parent’ well-being and mental health as they feel their recourses are put into use, and are contributing in the surrounding community. Mohamad et al. (2016).Pinquart et al. (2010) demonstrated an interconnection between elderly feeling isolated and the quality of people they spend their time with, or their social connections. These social connections for elderly people found to be crucial than the number of their social ties. Pinquart and his colleagues see that older adults have a weaker capability in connecting with their family and their relatives while often feeling loneliness than those whom their network consists of friends and neighbours. Armitage and Nellums (2020), Pinquart and Sorensen (2010).Having an extended family of two or even three generations residing in the same home can be a good thing. Multi-generational living works best when there is plenty of space so that everyone can get the privacy they need. Additional factors include mutual respect for one another, clear communication and a willingness to cooperate. Buheji et al. (2020).In such families, respect must be built into the living arrangement from the beginning, to avoid caregiver burnout and resentment among other family members. Adequate planning beforehand is crucial for helping to ensure that living with ‘ageing parents’ is successful.

2.4. Influence of COVID-19 Pandemic and Lockdown on Ageing Parents and their Caregivers

- The unprecedented reality of COVID-19 pandemic forced many families either continue to be separated or come to live together; depending on situation and extent of care needed, and whether there are some people in the family cannot follow the social distancing due to i.e. being a front-line worker. Bhanoo (2020), Flegar et al. (2020).Some ‘ageing parents’ simply found themselves trapped in what was supposed to be a temporary situation. Many of these parents became in a devising long waiting situation, where they cannot travel alone to go back home. In some countries, the impact on caregivers during COVID-19 was recognised by paid care leave, or flexible work arrangements, or focused training, or psychological interventions, as well as cash benefits, to support mitigating negative impacts. In most countries, such caregivers’ services remain limited and without any clear compensation, training or support. Bhanoo (2020).WHO (2020) declared that advent of COVID-19 pandemic had led many caregivers to adjust or give up their jobs to provide care or to avoid exposing the person they support to the risk of a COVID-19 infection. Caregivers working in the informal economy, as per WHO also have experienced reduced working opportunities due to restrictions, posing a risk to their income; thus they require support for the financial impact of the pandemic. O’Donnell (2020).Schlaudeker (2020) seen that family members should be considered to be critical partners in ‘ageing parents’ care during crisis times of the pandemic. Therefore, Schlaudeker called for revising many health policies to allow family presence at the bedside of their loved ones. i.e. a daughter who feeds her bedbound mother lunch, or the husband who combs and braids his wife's hair every morning, despite her anoxic injury that prevents her spoken word, are not visitors in our buildings. Goodman and Bubola (2020).

2.5. Empathetic Perception of ‘Ageing Parents’ Struggle

- Being an empathetic thinker, one would think deeply about the struggle of the ‘ageing parents’ and their living situation. Depending on the ‘ageing parents’ demographics, i.e. their age, health situation, life-time experience, profession, activity along with family history and their relations together; we can perceive their level of struggle. Therefore, compassion is considered part of the optimal geriatrics care today. This created new protocols that require that family members be allowed at the bedside of their ‘ageing parents’ not only in the final hours of life. It is crucial for family caregivers to take into consideration the dignity of the ‘ageing parent’. This can be achieved by encouraging these parents to indwell with their children while taking risks. To support the empathetic approaches towards our ‘ageing parents’ safety communication plan is required during times of pandemic. This plan should help the specific family members to make the decisions at the right time to protect the physical and mental health or the ageing parent. Buheji et al. (2020).

2.6. Knowledge-Transfer During Living with ‘Ageing Parents’

- Living with parents give us a great opportunity to ensure effective knowledge-transfer, or knowledge-capture from them as ‘ageing parents’ to us as caregivers, Bhanoo (2020). During times of crisis, as COVID-19 pandemic, it is a time and a great opportunity that we get our ‘ageing parents’ accumulated life experiences and learn from their wisdom, while we share knowledge with them. This knowledge-transfer can be a two ways of communication.On a project held by All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in 2017, older adults most of whom were experiencing depressive symptoms due to boredom, found to feel positive when they have taken the role of teaching faculty at schools due to shortage of teaching faculty in Delhi. Chatterjee et al. (2020). The knowledge-sharing experience improved their positiveness and their purpose in life.The experience of sharing-knowledge with an ‘ageing parent’, especially those with neurodegenerative disorders or dementias can itself strengthen the bond between the caregiver adult children and their ‘ageing parent’. The experience of knowledge-sharing is creating further purpose and deep meaning of living with our ‘ageing parents’ at difficult times.

2.7. Difficulty in Living with ‘Ageing Parents’ that Exhibits Troublesome Dementia-related Behaviours

- Caring for ageing patients can be a significant responsibility for many members of the family, especially when the elder exhibits troublesome dementia-related behaviours. In this life-threatening pandemic of COVID-19, dementia-related behaviours create unsafe conditions that increase the conditions of ‘self-neglect’. This ‘self-neglect’ can be represented in the unsanitary, or neglecting possible cross-infection, Bhanoo (2020). The dementia ‘ageing parent’ can easily provide the medium for the contagious virus transfer; unless proper monitoring or care is given. This can provide a huge strain on the family life; especially if the family members have limited livelihood options, or being front-line workers. O’Donnell (2020), Butcher et al. (2001).

2.8. Guilt for Effective Caring for the ‘Ageing Parent’

- Uncertainty increases when we cannot manage ours guilts in the proper way for caring for our ‘elderly parents’ while balancing for our other life and livelihood commitments. O’Donnell (2020).To manage this guilt, we need to acknowledge our limitations to ensure knowing the variety of the ‘elder care’ options; especially for a devastating long-term pandemic. The literature still has a gap in addressing what compensates for adult day-care, or in-home care, during lockdowns and social distancing; especially also when nursing home proved not to be safe or not affordable in many situations. Kernisan (2020).

2.9. Power of Attorney on Behalf of Ageing Parent

- The other source of uncertainty is when to take the decision to take accountability for having the power of attorney (POA) of your ‘ageing parent’ affairs and assets. Living with an ‘ageing parent’ that used to be active, still functional and have a strong hardiness attitude while exhibiting troublesome dementia-related behaviours is a very challenging and risky decision.Even if you have the power of attorney documents naming you as the agent to act on the behalf or your ‘ageing parent’, activating this document and utilising it is highly challenging if you see that they still are functional despite their strange developing behaviours. It is important to remember that competent elders are entitled to make their own decisions — even bad or unsafe ones. The empathetic thinking comes here again to remind you that one day you will be in their shows. Having guardianship on ageing parents also gives us the responsibility of their wellbeing and their alternate living arrangements. The challenge would be when the ageing parent refuses the caregiving situation, then the responsibility for those changes falls on us.

2.10. Multi-generational and Inter-generational Living During Pandemics

- Berman (2016) shows that there is a fine line between caring and controlling. This dilemma especially increases in multi-generational living. We can see this dilemma increases as we have the new generation take the role of the previous other generations. Managing the many challenges of caring for our ‘ageing parents’ requires emphasis for struggles and successes. The challenge needs to be mitigated by a multidisciplinary team from geriatricians, social workers, assisted-living facilities therapist, besides an elderly care legal councillor. Sundararajan (2020).While home quarantine and social isolation are currently the most widely used measures to prevent the spread of Covid-19, and that is more effective, especially in ‘ageing parents’ with co-morbidities. Armitage and Nellums (2020) highlight the great ‘ageing parents’ psychological risks that come along with social distancing. Therefore, multi-generational and inter-generational living found to reduce depression, anxiety and even acceleration of brain ageing symptoms, or the feeling of low and isolated before the start of the pandemic. Armitage and Nellums (2020), Mohamad et al. (2016).Chatterjee et al. (2020) suggest an intergenerational living alleviate the burden of COVID-19’s social disconnection. This inter-generational living found to influence both of age extremes; i.e. ‘ageing parents’ feeling alone and young adults being bored and isolated. Chatterejee and Yatnatti (2020), Watson et al. (2012).

3. Methodology

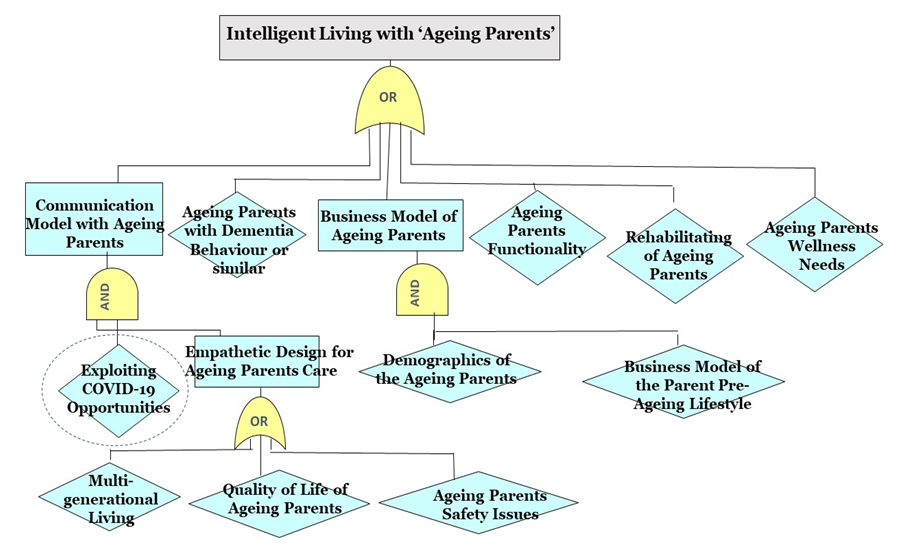

- Based on the literature reviewed, a framework that emphasises the importance of an intelligent decision making and communication framework with ‘ageing parents’ is proposed based on the work of Buheji et al. (2020). This paper would develop the framework further to help manage and continuously improve the quality of life of our loved ones, our ‘ageing parents’, through enhancing the accuracy or the empathetic thinking during the process of engaging with them. The framework proposed should help to compensate for the difficult ‘ageing parents’ such as those with dementia behaviour. The framework proposed should help to re-evaluate the boundaries with our ‘ageing parents’ whether they are living due to the global pandemic emergency, or due to the multi-generational living. The framework should help to extract tools that help in designing the best caring decisions and actions for our ‘ageing parents’ through assessing what type of business models our ageing parents used in their life, then building a new business model suites their current status, based on the analogy of previous business model. This would be one of our main milestones of properly caring for our ‘ageing parents’ since this business model would continuously be upgraded and modified to ensure their functionality. Sundararajan (2020).To optimise the COVID-19 pandemic opportunities that come from mitigating risks or safety measures; the framework included ‘wellness’ during even the national emergency crisis, Buheji and Ahmed (2020). The framework would work on joining both the wellness, the QoL of the ageing parents, and support its measurement through Activities of Daily Living (ADLs). Based on these results rehabilitating an ‘ageing parents’ would be proposed.

4. Framework Proposed

4.1. Establishing an Empathetic Design Framework

- This framework target to anticipate the potential changes that could result in our ageing parents' lives due to the status of the lockdown, or the spillovers of the COVID-19 pandemic and then the new normal. It is crucial to have realistic expectations of everyone involved or engaged in the framework, i.e. the ‘ageing parents’ and their children or their caregivers, based on their own setting. The more considerations given to these expectations will help in determining how living with an ‘ageing parent’ will affect the entire family dynamic. The empathetic design framework can be realised more when we build accountability of the caregivers in the multi-generational living, or when work for establishing the quality of life of the ‘ageing parents’, or develop their safety.

4.2. Intelligent Decision-making Framework

- To establish a dynamic, pragmatic and yet intelligent decision-making framework, the authors decided to the generative and flexible modular framework. Therefore, a logic framework using the (AND) and (OR) circuit design diagram is used t0 build an effective decision system that can support the proactive actions, or reactions, towards our ‘ageing parents' needs and wants during emergencies, or even in normal times. The (AND) symbol requires that all the inputs before the (AND) works in order to create an output, as shown in Figure (1). At the same time, the (OR) symbol tells the framework user or the reader to use any of the inputs before it to achieve the outcome.

| Figure (1). Framework Proposed for Intelligent Living with ‘Ageing Parents’ |

4.3. Communication Model with Ageing Parents

- In order to protect our ‘ageing parents’ and ensure effective and minimum communication, we need to consider every possibility to meet their expectations. Therefore, Figure (1) shows that in order to build this communication model, we need both an empathetic design for the ‘ageing parents’ care, besides exploiting the best communication pathways during an emergency situation as in the pandemic of the COVID-19. Morris (2014) states that it is vital to strengthen the ageing parent functionality through communication models. This means we need to build communication pathways based on the final proposed framework, as per the condition of the ‘ageing parent’. The communication model can be made by making sure not to withdraw the ‘ageing parents’ from doing some tasks and responsibilities that are within their capabilities; i.e. “fostering their independence”. This means that the ‘ageing parent’ should feel that they are still in control over their own lives and decisions, even if they did not refuse this takeover. When an older parent gets used to the loss of autonomy, i.e. even in not involving them in choosing to do simple tasks, such as getting dressed or doing a cup of tea, we could seize their mental stimulation and make them more susceptible to experience depressive symptoms.

4.4. Assessing the Business Model of the Parent Pre-Ageing Lifestyle and Their Current Demographics

- As parents get older, we need to enhance our attempts to empathetically realise how they want to live, think and survive. Once we apply empathy, we transform from being ‘caring about’, to being ‘caring for’. This would shift us from push-thinking to pull-thinking, i.e. from providing just more and more ‘physical living services’ to providing more ‘comprehensive wellness services’ where physical, mental, and feelings happiness give them more meaning for life. Waldinger (2018).This transformation from ‘push-thinking’ to ‘pull-thinking’ requires us to first assess the ‘business-model’ they used in most of their life, i.e. the way they lived most of their life, and the lifestyle that the ‘ageing parents’ spent and their level of wealth utilisation and independence. Empathetic thinking helps us to realise more why our ‘ageing parents’ become defensive or react, insist, resist, or persist in their ways or opinions.As per Figure (1) also we need to assess the demographics, age, type of specialty or job, income, etc. of the ageing parents so that and based on the lifestyle of the way they delivered most of their contribution in life we can create the most suitable business model for them as they become old.

4.5. Building the Business Model of our Ageing Parents

- Our ageing parents needs to be constantly assessed for the most suitable lifestyle they want to live in. Since some parents would suffer from memory, or would be in dementia behaviours, we need to estimate the most suitable business model they would love to continue the rest of their life with, or live at this stage of life.Suppose the business model of the ageing parent used to be dependent on others for shopping and used to focus on specific areas of interest then some of this business model need to be reflected in the newly designed way of life. Thus, we need to try a variety of strategies to see the level and the type of services and excitements that shape their most suitable wellbeing. This would help us to design the intergenerational relationships. Kernisan (2020) seen indirectly the importance of business models where many ‘ageing parents’ to minimise or specify the type of help they need from others, especially if they live now into their 80’s, 90’s, or beyond. Being fully independent in most of their business model in most of their life, one could go towards deceased independence of this model gradually. Giving our ‘ageing parents’ some dependence does not mean we need to intervene in everything in their life. When an ‘ageing parent’ starts to feel the need for help, some family members need to start contributing gradually and selectively towards compensating their needs. This selective support requires both an intelligent approach and unique sacrifice from all the family members living with the ‘ageing parent’.

4.6. Ensuring Ageing Parents Functionality

- The functionality of an ‘elderly parent’ is often controlled by both physical and mental health capacity. The more an ‘ageing parent’ have a large scope of functionality affecting his/her ability to remain independent and manage various aspects of life, the more they can have a realised independent business model that suits their choices.The proposed framework encourages the children caregivers to optimise the ‘ageing parent’ functionality by keeping for them a space to react, act and reflect.

4.7. Exploiting the COVID-19 Opportunities for the Benefit of Ageing Parents Functionality

- Buheji and Ahmed (2020) mentioned about finding opportunities inside the COVID-19 pandemic problems. Such opportunities can be achieved through exploiting the available non-financial wealth of the ‘ageing parents’. This non-financial wealth can be represented by their physical, mental, and spiritual wealth. Figure (1) shows that this (what if) box is surrounded by a dotted circle, to that it shows that this part of the framework could be replaced, as per the type of the emergency situation.

4.8. Rehabilitating Our Ageing Parents

- The proposed framework in Figure (1) also encourage rehabilitating our ‘ageing parents’ towards more effective functionality. This means that the caregivers should work to enhance their capacity to continuously see the value of their existence in life and even their capacity to participate in livelihood activities. When an ‘ageing parent’ starts to develop dementia, the availability of a suitable rehabilitation program will minimise the need for medication and frequent hospitalisation. Sudden or gradual more noticeable age-related cognitive changes need to be compensated with a well-established rehabilitation program. It is highly recommended that psychological and not only physical rehabilitation are done when an ‘ageing parent’ is also reluctant to accept help or make changes in their way of life.

4.9. QoL of Ageing Parents Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)

- The proposed framework in Figure (1) also addresses the importance of the quality of life (QoL) of the ‘ageing parents’. This QoL needs to be measured by Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) where their key daily life tasks are briefly described by this measure. The ADLs help to manage and develop our ‘ageing parents’ functionality, improve their business model, ensure their suitable wellness. This ADL would be a key for building an intelligence system that suite the type of the ageing parent. An example of Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) can include the capacity for managing the day to day living functions like cooking, communicating, using transportation, doing essential shopping, and following home maintenance. The framework defines the ‘ageing parent’ needs and the type of assistance through calculating their ADLs and determining what kind of care arrangements they need, especially during lockdowns and COVID-19 pandemic.

4.10. Ageing Parents Safety Issues

- Besides addressing the different ‘ageing parents’ vulnerabilities, the framework in Figure (1) exploits all the possible arising needs, especially during a contagious disease. The framework helps to align the medical and health issues, especially if the parent older than 70 years and have chronic conditions. To define a family’s safety assistance for our ‘ageing parents’, the framework could guide the caregivers to set up both proper protection plans, and even to set up safety recovery plans should the illness enter the house of the family. Since serious illness or certain chronic conditions can cause our ageing parents to lose the ability to make their health decisions, or oversee their own medical care during a dangerous pandemic; there should be a clear decision-making plan, or communication plan within the family.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Importance of Empathetic Design for Ageing Parents Care

- When we imagine that soon we will become an ‘ageing parent’ similar to our loved one that we care for, surely, we will start to look at our role to them from different perspectives. The matter of ‘ageing parent’ care needs to be seen from different perspectives. For example, if you are having an ageing father still driving and you are worried whether you should interfere in his decision to continue driving or not, you should visualise if you were in his/her place what would be your decision. For example, if you are a mother or a father suffering from dementia behaviours, how would like your children deal with you?

5.2. Handling Dementia Ageing Parents Behaviour

- Dementia can complicate the caregiving we could offer for our ‘ageing parents’. We need to understand the specific type of patterns and the types of care we need to give such parents. ‘Ageing parents’ may exhibit manipulative behaviour as their cognitive status declines; therefore we might need to optimise further the use of the proposed framework in this study. Since there is no way of predicting how an ‘ageing parent’ will act because their progressive conditions and how the framework would manifest differently for each person, the ‘ageing parents’ and the symptoms change over time. The authors are living this experience now and trying to modify the model.

5.3. Re-evaluating Boundaries with Our Ageing Parents

- Setting and maintaining boundaries with our ‘ageing parents’ could help us in to build safe practices with high accountability. Since caring for elders is hard, we need to manage and sustain a level of independence for each party involved with giving emotional and practical care to our ‘ageing parents’. Buheji et al. (2020).We need to appreciate that the boundaries of our ‘ageing parents’ might go through stages that we might go through ourselves. Besides the possibility of the chronic diseases, memory losses, and impaired logic and another type of dementia behaviour need to be managed carefully to create a healthy emotional living for both the ageing parent and the parent carer. Knowing the level of dementia eventually helps the caregiver to manage or control the ‘ageing parent’ moods physical health, and behaviour.

5.4. Managing the Quality of Life of Difficult Ageing Parents

- When the family member we are trying to care for is critical, impossible to please or emotionally abusive, long-standing family dynamics are often to blame. When our elders suffer from chronic pain, or when we have little control over their moods and behaviours because of Alzheimer’s disease or another type of dementia, we need to find a solution for both their health maintenance, and manage to memory that mitigates the dementia behaviours. Buheji et al. (2020), Butcher et al. (2001).The little kid inside of us most likely still wants our parents’ approval. When we are denied that validation, even as adults, it hurts. The challenge is how to bring in a solution that is best for us, best for our ‘ageing parents’ and our family. One of the possibilities is to put a family geriatric care manager that can conduct an assessment of our ‘ageing parents' needs and recommend options for their care.

5.5. Final Words

- This paper has many implications that encourage multidisciplinary approach for caring for any ‘ageing parent’. The paper is suitable as a guideline for practitioners and family members or an ‘ageing parent’ carers. The other implication of the proposed framework would help us make informed choices.The limitation of this paper is that the framework did not go into the details of the (what if) or the diamond box and stayed in high-level flow design only. The other limitation here is the scope of this paper did not cover what the ‘ageing parent’ could do themselves. This paper, however, can also be applied to ‘ageing parents’ who are reluctant to accept help or make changes in their life.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML