-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2020; 10(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20201001.01

Effect of Cognitive Restructuring and Assertive Therapies on the Reduction of Depressive Tendencies among Colleges of Education Students

Virginia Nnenna Madu

Federal College of Education, School of General Education, Department of Educational Psychology, Hospital Road, Obudu, Cross River State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Virginia Nnenna Madu, Federal College of Education, School of General Education, Department of Educational Psychology, Hospital Road, Obudu, Cross River State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study was an investigation on the effect of cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies on the reduction of depressive tendencies of students in Colleges of Education in Cross River State of Nigeria. The study was an intervention for students who were experiencing depressive symptoms. Five research questions and five hypotheses were formulated to guide the study. Related literature to depressive symptoms were reviewed. The design of the study was quasi experimental. The population comprised 234 students who were experiencing depressive tendency. The sample consisted 90 out of the 234 students, and this was systematically drawn. The instrument for data collection was Beck`s Depression Inventory (BDI-II). The treatments which were cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies were administered on two experimental groups for eight weeks while the control group had discussion on great heroes and heroin and their ideologies. Mean was used in answering the research questions while ANCOVA was used to test the hypotheses at 0.05 level of significance. The result summarily showed that both cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies had positive effects in reducing students depressive tendency. Cognitive restructuring was more effective than assertive therapy in reducing students` depressive tendency. However the difference was not significant. There was no difference in the reduction of depressive tendency of male and female students in cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies respectively after intervention. In line with the findings, it was recommended among others that Psychologists and Guidance Counsellors be encouraged to use cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies in reducing students` depressive tendencies.

Keywords: Cognitive Restructuring (CR), Assertive Therapy (AT), Depressive tendency, College of Education students

Cite this paper: Virginia Nnenna Madu, Effect of Cognitive Restructuring and Assertive Therapies on the Reduction of Depressive Tendencies among Colleges of Education Students, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20201001.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

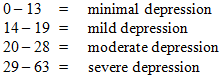

- Sound mental health is a prerequisite for active and productive life. Active processing of information that characterizes academic enterprise could be hampered by a poor mental health. One of the common mental health issues is depression. Depression is a mood or affective disorder characterized by inactivity, insomnia, early morning awakening, diffused anxiety, poor appetites, loss of energy, sadness and inability to concentrate (Omeje, 2005). Omeje added that depression can be conceptualized along the continuum of mild, moderate and severe but not psychotic to psychotic depression. This conceptualization refers to the levels of severity and agrees greatly with that of Beck (1996). According to Beck (1967), depressed persons are dominated by negative views of self, the outside world and the future. Beck also postulated that depression is in levels which are severe, moderate, mild and minimal depression.All the definitions of depression above including those of Hahn and Payne (1999), Youngson (1992), Accardo, Whitman, Beht, Fanell, Magenis & Morrow-Carton (2002), Mayoclinic (2018), WHO (2019) which space will not permit to state here reflect symptoms of depression. Equally important are the symptoms of depression as given by American Psychiatric Association (1994) as outlined in their Diagnostic and Statistical manual for mental disorders (DSM-IV) which are as follows: depressed mood most of the day, markedly diminished interest in almost all activities; significant weight loss or gain or appetite disturbance; insomnia or excessive sleeping; restlessness; low energy level, feeling of inadequacy, decreased concentration, recurrent thoughts of death.There are three main points of view about the causes of depression, which are; depression is a medical disease caused by neurochemical or hormonal imbalance; depression is caused by certain styles of thinking; depression is a result of unfortunate experiences. Although certain individuals might be biologically disposed to experience depression, and unfortunate experiences may have its role; one’s attitude toward these situations can ameliorate or exacerbate depression.One of the reasons why students may be at risk of depressive symptoms is that there is no age barrier for depression. Depression can affect anyone including children (Maag, 1986, Benefield, 2006, & Artalejo, 2006,). Evidence of major depressive disorder among students is reported by the following, both outside and within Nigeria (Benefield, 2006; Adewuya, Ola, Aloba, Mapaya, & Ogini 2006; Adeniyi, Okafor, Adeniyi, 2011 & Mullen, 2018). Some of these reports range up to 23% including suicide attempt which is worrisome.For the purpose of this study, a student is said to have depressive tendency if such student scores 20 and above on Beck’s Depression Inventory. Although according to Beck (1996), a score of 20 and above will fall under moderate to severe depression, in this study, such score defines one as having depressive tendency, since such students are in the normal population, going about their studies.Result from 2004 Minnesota student survey served as the catalyst for interest in the topic of depression prevention and treatment among students. The result indicated higher prevalence of depressive symptoms among females. In this work, it is important to compare the response rate of male and female students experiencing depressive symptoms.The associated cost of depression include substance abuse, academic problems, higher-risk sexual behaviour, physical health problems, impaired social relationship and increased risk of a completed suicide (Horowitz & Garba 2006; Chui, Lebenbaum, Cheng, Oliveira, & Kurdyak, 2017). It becomes pertinent for an intervention in order to minimize the depressive tendency and to prevent the students from developing full blown depression.Cognitive restructuring (CRT) is a core technique from cognitive therapy. It involves the application of learning principles to thoughts. The technique is designed to help individuals alter their habitual appraisal habits so that they can become less biased, resulting to a better emotional response. Cognitive behavioural therapy was first known in the form of Albert Ellis Rational Emotive Therapy (RET); Later Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT), and Aaron Back’s Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).Beck’s explanation of negative automatic thoughts as being tied to depression and how it is to be identified and modified, provides a guide to cognitive restructuring. Beck’s cognitive theory therefore provides a base for this study. In order to have insight into areas of students’ problems, a psychological test needs to be administered. Beck Depression Inventory (1996) is very helpful in exposing areas of students’ problems through symptoms reports. Once the problem is identified, both the Educational psychologist and the student specify the problem, and what to change. Through discussion with the students the automatic thought over the situations are identified including the nature of cognitive biases such as overgeneralization, selective abstraction and catastrophizing. This underscores the need for cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring is operationally defined as the identification of unhealthy thoughts through self-monitoring and the modification of such biases by considering their antecedents and consequences in order to make better appraisal.The behavioural component of depressive tendency requires that the behaviour associated with it be changed in order to avert the ugly circle. One of such behaviour is unassertiveness. This calls for assertive therapy. Assertion according to Lewinsohn, Munoz, Youngren, and Zeiss (1986:73) consists mainly of expressing one’s complaints, being insistent in demanding service, and refusing inconvenient requests from others. It is a response that seeks to maintain an appropriate balance between passivity and aggression.Assertiveness agrees with behavioural medicine technique advocated by Compass, Haaga, Keefe, Leitenberg and Williams, (1998). In this work assertion is operationalized as frankly expressing one’s thoughts and feelings without infringing upon the rights of others. It includes voicing out complaints, feelings of warmth and affection, inviting others to share an activity, and letting others know about one’s hopes and fears.Available research evidence suggests that depression relates to learning difficulty (Bonifacci, Candria, and Contento (2007); Brumbach, Mokros, Posnanki and Merrick (1989); Ugokwe-Ossai and Ucheagwu (2008). Thus there is need for intervention.Cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies are techniques of cognitive behavioural therapy. Empirical data from carefully conducted studies demonstrate that cognitive change may occur using environment-based manipulations or cognitive intervention (Jacobson, Dabon, Truaz, Addis, Knexyer, Gollan et al cited in Hopko, Lejuez, Ruggiero, & Eifert 2003; Driessen & Hollon 2010). Since both cognitive intervention and behavioural activation result in cognitive change and cognition plays a motivational role in human behaviour, both cognitive restructuring and assertive therapy will likely yield the same result (reduction in the experience of depressive symptoms).There is paucity of literature on the response rate of male and female to treatment. Again control group is usually, a non-active comparison condition which deprives the group of serendipitous or non-specific treatment effects such as participant’s expectation (Shultz and Mueller, 2007). This study takes care of that by using active control group. The issue of intervention for reducing depressive tendencies amongst students in institutions of higher learning in Nigeria has not really been addressed. Uwaoma, (2006), Adewuya, et al (2006), Adewuya et al (2007) had advocated for such intervention, hence this study.

1.1. Purpose of the Study

- The objectives of this study are to investigate the effects of cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies on the reduction of depressive tendency, and to compare the relative effectiveness of the two therapies in reducing depressive tendency, find out gender differential in the reduction of depressive tendencies of male and female students expose to both cognitive restructuring and assertive therapy, and equally explore any interaction effect due to cognitive restructuring, assertive therapy and gender.The following research questions were raised to guide the study; 1. How effective is cognitive restructuring therapy in reducing students’ depressive tendency?2. How effective is assertive therapy in reducing students` depressive tendency?3. Which of the two therapies (cognitive restructuring or assertive therapy) is more effective in reducing depressive tendency of students? 4. What differences exist in the reduction of depressive tendency of male and female students who received cognitive restructuring therapy? 5. What differences exists in the reduction of depressive tendency of male and female students who received assertive therapy?The following hypotheses were formulated to guide the study, all tested at 0.05 level of significance.Ho1 There is no significant difference in the mean depressive tendency scores of students exposed to cognitive restructuring therapy group and those in the control group. Ho2 There is no significant difference in the mean depressive tendency scores of students exposed to assertive therapy and those in the control group.Ho3 There is no significant difference in the mean depressive tendency scores of students exposed to cognitive restructuring therapy and those exposed to assertive therapy. Ho4 There is no significant difference in the mean depressive tendency scores of male and female students exposed to cognitive restructuring therapy.Ho5 There is no significant difference in the mean depressive tendency scores of male and female students exposed to assertive therapy. Ho6 There is no significant cognitive restructuring, assertive therapy and gender interaction of students mean depressive scores.

2. Method

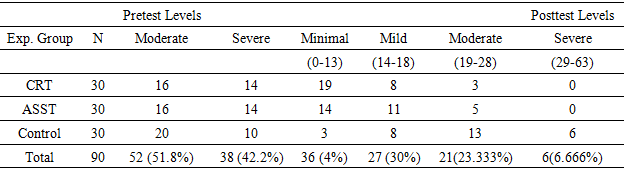

- This study adopted the quasi-experimental design. Specifically, the quasi-experimental design adopted the pretest posttest control group process. This study was carried out in Federal College of Education, Obudu (with two campuses), and College of Education, Akamkpa, both in Cross River State, South South Geopolitical zone of Nigeria. Cross River State is one of the 36 States in Nigeria. It is located within the tropics and has eighteen Local Government Areas. The State lies between latitudes 5°32/ and 4°27/ North of the Equator, and longitude 7°50/ and 9°28/ East of the Meridian. The total population of all the year two students used in the study was 3803 (2,431 students from Federal College of Education, Obudu and 1,372 from College of Education, Akamkpa. Out of this number, 780 students were screened and 234 representing 30 percent of the number screened were found to have depressive tendency. The total population of the study was therefore 234 students. The sample for the study comprised 90 out of 234 NCE II students who scored 20 and above on Beck’s Depression Inventory Version Two (BDI-II). This was determined by systematically selecting the first 15 males and first 15 females from each of the three campuses. The choice of e,ual number was to make the groups as homogenous as possible and to have a manageable number for treatment. On the whole, the sample comprised 45 male and 45 females. The mean age of the students is 23 years, mean age of the males is 23.5 years while mean age of the females is 22.11 years.Beck Depression Inventory was used for data collection, namely; for identification of the depressive symptoms scores (pre-test and post-test). BDI-II is positively correlated to Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and coefficient of concurrent validity yielded 0.71 (Beck Depression Inventory-WIKIPEDIA, the Free Encyclopedia). BDI-II was further validated by the present researcher for the purpose of this work. A coefficient of concurrent validity of 0.97 was obtained between Zung’s Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) and BDI –II. BDI-II was also shown to have a high one week test-retest reliability (Pearson r=.93). The reliability of the instrument for Nigerian population as given by Okoli (2009) was r (60) = .76, using spearman Brown plit-half, and by the present researcher r (10) = .98 using Kuder Richardson’s 21(KR-21). The researcher adopted the following procedures in order to control some of the identifiable variables that may have effect on the dependent measure.The two experimental groups and the control group were paired on the variable of the study, namely, having depressive symptom (as much as score 20 and above on BDI-II).They were equally matched on gender and level of NCE (II). Finally, the researcher used analysis of co- variance (ANCOVA) in analyzing the data. Using the pretest measure as a co-variant, this technique makes necessary adjustment on the dependent measures in order to correct any initial differences between the experimental and control group (Ferguson, 1981, Hincle, Wiersma and Jurs, 1990). The research assistants were trained using the treatment model prepared by the researcher. Specifically, two research assistants were trained for Assertive Therapy group and control groups, while the researcher handled Cognitive Restructuring group. The training lasted for two days since the research assistants are authorities in the field. The duration for the therapies was for eight weeks of one session per week lasting for 60minutes. In each therapy, three stages were involved namely, assessment or interview, introduction to therapies, termination and posttest.Mean was used to answer the research questions while Analysis of Co-variance (ANCOVA) was used to test hypotheses at 0.05 level of significance. Greater mean loss means greater improvement. The scoring key also served the purpose of showing how the students migrated from their levels of depressive tendencies at the beginning of the treatment to other levels after intervention. The scoring is as follows

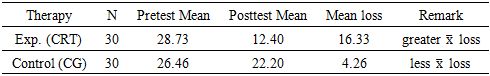

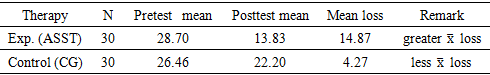

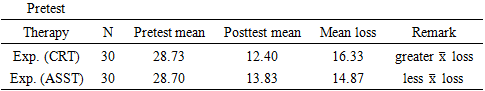

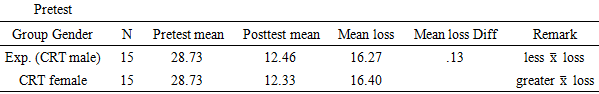

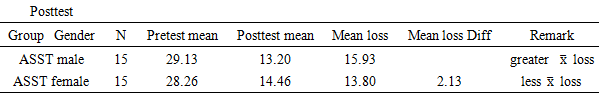

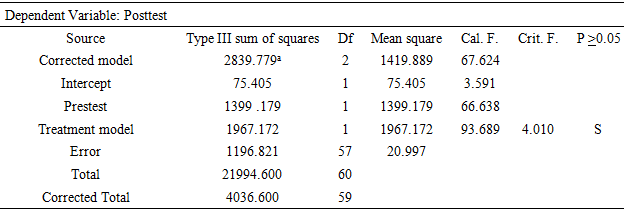

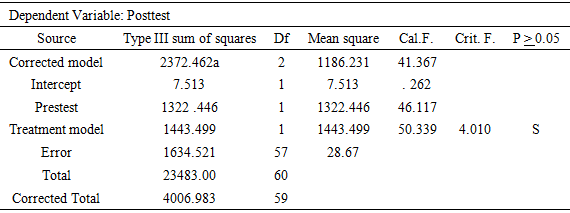

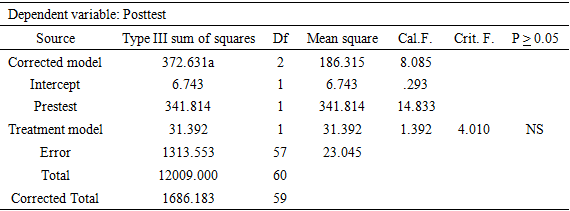

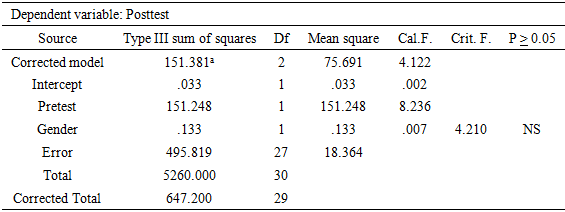

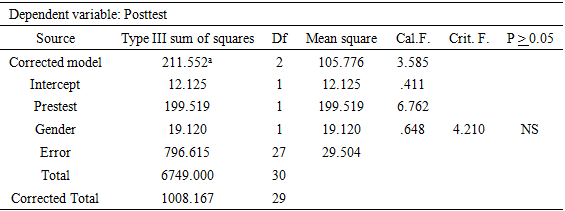

3. Results

- The results are presented based on the research questions and hypotheses that guided the study.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.1. Discussion of Findings

- The result of this study showed that cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies had a significant positive effect in reducing students’ depressive tendency. This result confirms Dumbeck and Well-Moran’s (nd) postulation that cognitive restructuring is designed to help people alter their habitual appraisal habits so that they can become less biased, resulting to a better emotional response. It also validates the assertion of Ivancevich-Konoparke, and Matteson (2005) that cognitive restructuring is amenable to wide range of situations and stressors, and is particularly attractive as an individual stress management strategy. It is important to note that stress pave room for the development of cognitive biases which give room to depressive symptoms when it becomes automatic, and if not managed well could lead to full blown depression. The findings also agree with that of Gillham, Reivich, Freres, Lascher, Litzinger, Shatte Saligman (2006b) who used Pen Resiliency Programme (which is a form of cognitive restructuring) as secondary intervention in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety among youths and found it effective.Also the fact that assertive therapy was able to reduce the depressive tendency of students lends credence to Hopko, Lejuez, Ruggiero and Eifert’s (2003) report that environmental based manipulation and behavioural activation, just like cognitive intervention can result in cognitive change. As such, the assumption that since cognition plays a motivational role in human behaviour, both cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies would likely reduce the experience of depressive symptoms was confirmed.This result showed that gender was not a significant factor influencing student’s response to either CRT or ASST. This agrees with the findings of Gillham, Reivich, Freres, Lascher, Litzinger, Shatte Seliman (2006b) that students did not differ by gender in their response to pen resiliency programme which was also designed to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety among students. Male students in both cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies improved more than female students placed in both therapies. The reason for the slight difference observed in gender main effect (in favour of males) could be attributed to the fact that male students are more pragmatic, more outgoing and more assertive than female students. On the other hand, the result differed from the findings of Okoli (2009) who conducted a study on the influence of psychotherapy and gender on depression using 60 participants who were university students. In this finding, gender was a significant factor influencing student’s response to psychotherapy. The psychotherapies used by Okoli were positive self-talk, exercise and a combination of self-talk and exercise. Okoli did not state the group where the significant difference existed, for more insight.Result showed that there was no significant difference in the reduction of depressive tendency of students due to either cognitive restructuring or assertive therapy. This result agreed in part with Unigwe (1998) who used systematic rational restructuring technique and contingency contracting techniques to reduce truant behaviour among secondary school students. Unigwe (1998) found the two techniques effective just like CRT and ASST were found effective in reducing depressive tendency.

4. Conclusions

- Based on the results obtained, the researcher drew the following conclusions: (1) Cognitive restructuring and assertive therapies were effective in reducing students depressive tendency; and between the two intervention programmes (CRT and ASST), there was no significant difference in their level of effectiveness in reducing students depressive tendency.(2) Similarly, the treatments proved superior to the control group which received place intervention in reducing students’ depressive tendencies.(3) Gender was not a significant factor affecting student’s response to either CRT or ASST.

5. Recommendations

- The following recommendations were made based on the findings of this study.1. Secondary intervention for such group of learners should aim at the identification of negative automatic thoughts individuals express over difficult situations as a significant contributor to the experience of depressive symptoms, and focus intervention on such thoughts.2. Part of the intervention aimed at reducing depressive tendency should focus on identifying behaviours associated with depressive tendencies and replacing them with more adaptive ones.3. The curriculum for secondary and tertiary institutions of learning should reflect life skill training to be taught to learners at this level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author remains indebted to the following professionals, for their contributions to this work; Prof E.C. Unachukwu of Department of Educational Foundations, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. He supervised this work.Prof P. O. Ebigbo of University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus who helped the researcher to have a clearer understanding of certain issues concerning this topic. He is a consultant Psychiarist and Head, Child and Adolescent Psychiartry Unit, Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital Enugu, Nigeria. He was the first West African to be elected into the International Council for the Rehabilitation of Torture victims. He actually referred the researcher to Prof B.Y. Oladimeji (a Psychotherapist of CBT orientation) for more information.Prof (Mrs.) B.Y. Oladimeji made a significant contribution to this work. At the time this work was carried out she was a Clinical Psychologist at Obafemi Awolowo University Ife and Secretary to the Nigerian Association of Clinical Psychologists. She advised that the research be carried among students.The researcher is also thankful to Dr U. Nwokwu of Federal Ministry of Health, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State and Dr I. Onyia (now late) of St Gerald`s Clinic Vandeikya, Benue State for their useful suggestions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML