-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2019; 9(2): 19-25

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20190902.01

Investigating Resilience, Job Search Self-Efficacy and Intentions from Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior and Social Cognitive Model of Self-Career Management

Duong Nam Tien

Ph.D Candidate in Yuan Ze University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan

Correspondence to: Duong Nam Tien, Ph.D Candidate in Yuan Ze University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The current study aimed to test the relationships among job search (JS) self-efficacy, JS intentions and resilience from integrating theory of planned behavior (TPB) and social cognitive model of career self-management (CSM). Specifically, the study focused on the impact of one personality characteristic (e.g. resilience) on the relationship between JS self-efficacy and intentions. With a sample of 301 Southeast Asian students who are currently studying in Taiwan, we found that JS self-efficacy greatly predicted JS intentions. Simultaneously, JS self-efficacy has a partial mediating effect on the correlation between JS intentions and resilience. Therefore, the impact of the personality characteristic on JS intentions is direct and also indirect through JS self-efficacy. The results provide practical insights in improving self-efficacy and intentions among graduating job seekers and how to enhance their resilience levels during JS process.

Keywords: Job Search Self-Efficacy, Job Search Intentions, Resilience, International Students

Cite this paper: Duong Nam Tien, Investigating Resilience, Job Search Self-Efficacy and Intentions from Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior and Social Cognitive Model of Self-Career Management, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 9 No. 2, 2019, pp. 19-25. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20190902.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- One of the most dominant theories that have been the focus of job search is the theory of planned behavior (TPB), in which people with stronger perceived behavioral control or self-efficacy (Ajzen, 1991) will have more intentions to be engaged in behaviors. The TPB also posited that self-efficacy is among the most important predictors of JS intentions. The TPB has been reported to be crucial in previous studies relevant to JS outcomes and behaviors with intention as the core variable (Ajzen, 1991). Specifically, the stronger intentions have a greater impact on behaviors in JS (Van Hoye, Saks, Lievens, & Weijters, 2015). However, as a drawback, the TPB only focuses on its immediate determinants (e.g. perceived behavioral control or intention) without examining their precursors. Meanwhile, the social cognitive model of career self-management (CSM), one of the most dominant models of vocational development, provides a broad framework including the relationships of contextual and personality traits with career–related performance behaviors. The CSM focused on individual capabilities and personality during JS or vocational development processes. To date, there have been many studies that separately examine the application of one or more variables from both TPB and CSM. However, there is little attempt to integrate the variables from these two theories into one model. Social cognitive model of career self-management (CSM), a dominant model of vocational development, provides a broad framework including the relationships of contextual and personality traits with career–related behaviors. The CSM focused on individual capabilities and environmental resources during behavioral processes. The CSM also explains how people employ “adaptive career behaviors” to self-direct their career (Lent & Brown, 2013). Therefore, the CSM can provide a perspective to examine the core variables in the TPB. The CSM has emphasized not only on activity domains but also personality (e.g. ability to adaptation to outside environments) as sources of self-efficacy that helps job seekers to be more likely to persist until success. Especially, one highlighted point that has been tested in previous studies is related to the direct path from personality variables (e.g. conscientiousness) to self-efficacy (Lim, Lent, & Penn, 2016). When it comes to job searching, international students could be a targeted population that is worthy of further research attention. The workforce mobility has recently been growing due to the worldwide economic crisis that has been followed by job losses and pursuit of job opportunities (Van Hoye, Saks, Lievens, & Weijters, 2015). In the meanwhile, in the trend of globalization and internationalization, there has been an increase in the number of international students in many countries (Brunton & Jeffrey, 2014; Khawaja, 2011). This trend calls for more research about international students’ vocational issues in host countries. International students not only enrich cultural awareness and appreciation, thus, increasing cultural diversity in host countries, they also contribute to the intellectual capital with their knowledge and skills in the workforce (Harrison, 2002; Khawaja, 2011; Tan & Liu, 2013). Compared to local students, international students also expressed great needs in career and gaining working experiences (Leong & Sedlacek, 1989). However, there has been a scarcity of literature review of vocational development among international students. Therefore, the study’s purpose is to integrate the TPB with the CSM so that the TPB determinants can be predicted from a personality characteristic. The sample consisted of international students in Taiwan, however, mainly from Southeast Asian graduating students due to the New South Policy launched by the Taiwanese government. In more details, two crucial variables of the TPB (JS self-efficacy and intention) were explained in the context of the CSM. Furthermore, resilience as a personality characteristic was used as a precursor in order to examine their relationships with JS self-efficacy and JS intentions from the CSM perspective.

2. Theoretical Background

- Richards and Johnson (2014) indicated that previous studies focused on testing and using simple theory to predict intentions and behaviors and there has been a lack of theoretical augmentation and comparison; thus, suggesting theoretical integration. In the area of JS, Van Hoye et al. (2015) proposed an integrative model that brought together the TPB internal variables with external ones. Besides, from the framework of social cognitive theory, it was indicated that there are the relationships among variables from self-regulation theory (SR) and the TPB (Zikic & Saks, 2009). To date, there have been many studies that separately examine the application of one or more variables from both TPB and CSM. However, there is little attempt to integrate the variables from these two theories into one model. In the present study, we aim to take a broader approach to understand the TPB from the CSM perspective. The integration of the two theories helps to deal with the drawbacks of previous studies that only focused on either the determinants or the influence of situational factors on searching behaviors without combining them both together (Van Hoye et al., 2015).The TPB and the CSM both posit that human behavior can be understood as the result of continuous, reciprocal interactions between three input sections: environmental variables, cognitive processes, and personality traits. These theories provide the broad foundations for a social-cognitive perspective on JS. These two theories emphasize the psychological mechanisms and processes by which an individual responds to his/her environment and manages the cognitions, affect, and behaviors for the purpose of gaining jobs. These two theories both fall within the wide social cognitive perspective that emphasizes person–environment transactions. However, the TPB excludes personality traits in the model. While the CSM can provide personality traits as individual differences that exert influence on an individual’s self-efficacy and intentions in the TPB. In brief, the relationships between JS self-efficacy and intentions in the TPB can be investigated together with a personality trait from the CSM.JS is a rather lengthy process toward a distal goal (i.e., obtaining a job) with lots of obstacles, setbacks, and rejections along the way. JS occurs in a rather competitive context because one often has to compete against other job seekers and applicants during the JS, job pursuit, and application process, especially for international job seekers with much more difficulties in comparison to local job seekers. Consequently, JS can easily distract job seekers’ attention and undermine their motivation. Due to the complexities, difficulties, and rejections associated with job seeking, JS activities are rarely considered to be joyful, pleasant, and amusing. In contrast, JS is often considered aversive and demands one’s great efforts. For tasks/activities that are unpleasant, boring, aversive and full of difficulties, but are of importance to attain some valuable goal (i.e., finding a job), job seekers need factors (i.e., ability or resilience) for task persistence and performance as well as overcome factors that undermine their motivation in order to cope with the outside environment. (Ajzen, 1991; Brown, 2013). Thus, resilience is considered to be a suitable personality characteristic construct that needs to be examined during JS process along with the main constructs such as JS self-efficacy and intentions.

2.1. JS Self-Efficacy and Intentions

- Perceived behavioral control in the TPB was re-conceptualized to be JS self-efficacy in the CSM, which asserts that a job seeker was confident that he is able to perform JS behaviors such as preparing resumes or attending job interviews (Ajzen, 1991; Song, Wanberg, Niu, & Xie, 2006; Van Ryn & Vinokur, 1992). Therefore, JS self-efficacy can be a strong predictor and determinant of performance -related goals in the context of the CSM. JS self-efficacy has empirically been reported to be predictive of JS intentions (Hooft, Born, Taris, Flier, & Blonk, 2004; A. M. Saks, J. Zikic, & J. Koen, 2015; Van Hoye et al., 2015; Zikic & Saks, 2009). Yet, some previous studies revealed that JS self-efficacy was not highly correlated with the intention (Song et al., 2006; van Hooft, Born, Taris, & van der Flier, 2004). All of the mixed findings in regard to the relations among JS self-efficacy, intentions were explained due to the fact that items measuring these two constructs were not compatible with each other (Hooft et al., 2004; A. M. Saks et al., 2015; Van Hoye et al., 2015). Hence, there is a need to clarify the relationships between these two variables in a different context.Besides, it should be noted that although self-efficacy has been widely recognized for its applicability in various populations, relatively few studies (Lin, 2011) about JS self-efficacy has been carried out among international students. Prior studies suggest that international students may deal with challenges, barriers (e.g. cultural and language barriers, race discrimination) within their time away from home (Lin & Flores, 2011; Sherry, Thomas, & Chui, 2010), which may have negative influence on their academic and vocational development. Meanwhile, JS self-efficacy has empirically been reported as a booster for positive beliefs and coping ability leading to positive JS behavioral intentions in stressful situations (Schaffer & Anne Taylor, 2012). JS self-efficacy becomes a coping resource for goal-oriented intentions in terms of intensity or efforts in the search process, even in the face of failures or stresses. Consequently, JS self-efficacy should be worth further examination when we investigate career-related intentions among international students in host countries.

2.2. Resilience, JS Self-Efficacy and Intentions

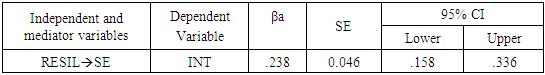

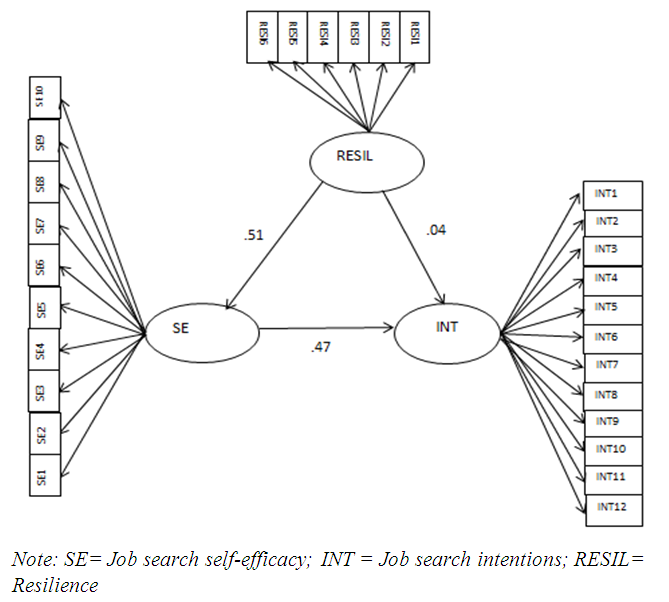

- Resilience is defined as a competence or ability to cope with stress or negative events (Hamill, 2003). However, it should be noted that resilience is a capacity to bounce back when an individual encounters failures/loss. It is a different construct from self-efficacy, which means a person’s self-confidence in specific skills/actions such as JS activities. With self-efficacy, one’s motivation, cognition can be mobilized in order to he/she can be able to exert control over a certain event. However, after adversity and affective reactions, self-efficacy can be undermined and need to be restored. Therefore, one will need resilience so that he/she can persist in his/her efforts. In other words, resilience serves as a coping trait that can be helpful for self-efficacy restoration. Consequently, in the context of JS, an adverse/challenging process, resilience may play a vital role in successfully searching for jobs. Resilience helps to sustain one’s long-term efforts and self-efficacy, which determines a success in JS. This is the reason why resilience is worth being included in the research model.On the other hand, even though resilience is viewed as a personality characteristic, resilience can be trained by learning some adaptive skills (Foumani, Salehi, & Babakhani, 2015). Resilience as a personality characteristic has been shown to be significantly correlated with personalities of neuroticism, extraversion and conscientiousness in Big Five personalities. This means that a person with positive affective styles can find it easier to deal with unpleasant situations (Cheng & Furnham, 2002).Individuals with high self-efficacy can sustain their efforts when facing failures and obstacles. They also quickly recover their self-efficacy perceptions (Bandura, 1994). In this sense, self-efficacy is associated with resilience which typically refers to the development of ability or skills in the face of setbacks or misfortune. This is a process which refers that an individual in adversity can dynamically and positively make adaptations to (Hamill, 2003). While both local job seekers and international job seekers are generally motivated by life and career opportunities, international job seekers tend to be more ambitious and assertive (Chiswick, 2000). Moreover, Boneva and Frieze (2001) suggests that international job seekers’ job searches may highly depend on their personality characteristics for a greater need for power and work achievement in more advantageous socioeconomic contexts. As such, in such an aversive process like JS, a personality characteristic can have a big impact on JS intentions and employment attainment. A personality characteristic such as resilience can be helpful for job seekers who desire to overcome difficulties or failures probably encountered on the way to job recruitment. It is due to the ability to adjust easily to the foreign labor market and to exert influence on it.In the CSM, resilience can be conceptualized a personal variable that facilitates adaptive behavioral intentions involving coping with difficult situations (Lent & Brown, 2013) directly or indirectly via self-efficacy. In other words, the increase in the level of resilience can lead to the increase in the level of self-efficacy. Many studies have found the critical positive correlation between resilience and self-efficacy among students indicating that resilient students have a strong sense of self-efficacy (Cassidy, 2015; Hamill, 2003). In the scope of JS, studies found JS self-efficacy positively correlates with personal traits (e.g. conscientiousness, extraversion, core self-evaluations in the Big Five personality factors) which are also relevant to adaptive behaviors (Lent & Brown, 2013; R. W. Lent, Ezeofor, Morrison, Penn, & Ireland, 2016; Lim et al., 2016; Van Hoye et al., 2015). In contrast, personality such as neuroticism may negatively influence self-efficacy, behavioral performance and coping tendencies (Brown, 2013). However, there has little research that examines the relationship between resilience as a personality characteristic and JS self-efficacy. Consequently, in this study, resilience is re-conceptualized as an individual personality characteristic that can used to predict individual self-efficacy of searching behaviors in the paradigm of the CSM.By integrating the two theories, we expect that (1) JS self-efficacy is positively related to JS intentions. (2) Resilience is positively related to JS self-efficacy. (3) Resilience is positively related to JS intentions; (4) JS self-efficacy has a mediating effect on the relationship between resilience and JS intentions.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedures

- Questionnaires were designed and delivered in person and online as well. The participants consisted of South East Asian graduating students who are studying in colleges and universities in Taiwan (N=301). Respondents participated in the questionnaires as part of the study. A total of 51% are female, 49% are male. The participants were primarily from Vietnam (55%), Indonesia (29.5%), Malaysia (7%), and Thailand (8.5%). They reported to be Master students (58.7%), Ph.D. students (25.7%), and Undergraduate students (15.5%). Among the participants, the age of 26-30 accounted for 52.4%, age of 19-25 (27.7%), age of 31-40 (19.4%), and 41-49 (0.5%). Most of them (70.9%) reported to be the first experience of overseas study.

3.2. Measures

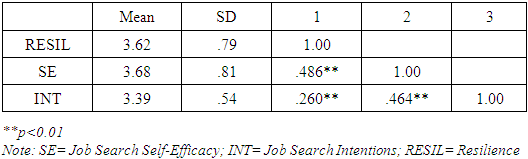

- Job search self-efficacy. The construct with 10-item scale measurement was based on the self-efficacy scale by A. Saks, J. Zikic, & J. Koen (2015). The same scales have also been used to assess JS self-efficacy (Côté, Saks, & Zikic, 2006; Saks, J. Zikic, & J. Koen, 2015; Zikic & Saks, 2009). Because this focus of this study was to investigate SEA students’ JS behaviors, the items used focused on JS behaviors. The respondents were asked the extent of confidence they had to successfully searching for jobs in Taiwan using the scale of 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (totally confident). The reliability coefficient was .96 in the current study.Job search intentions. The construct with 12-item scale was based on Blau (1994). One additional item about host country’s working visa was added to the scale (Lin & Flores, 2011). The scale was found as validation evidence that JS intentions can be measured (Hooft et al., 2004; Saks & Ashforth, 1999; Zikic & Saks, 2009). In this study, due to the fact that the participants might not have started searching jobs, they were asked about the extent to which they probably perform each of the following preparatory and active activities in the upcoming 6 months. The scale ranges from 1 (never 0 times) to 5 (very frequently – at least 10 times). The reliability coefficient in the current study was .95.Resilience. The instrument of the construct was from the brief resilience scale (BRS) (Smith et al., 2008). The measurement consisted of 6 items with reverse scoring, in which 3 items were in positive words, the other 3 items were in negative words. The samples are as follows: positive words - “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times” or negative words - “I have a hard time making it through stressful events”. The reported coefficient α was .80 to .91, respectively.Table 1 shows that there are correlations among JS self-efficacy, intentions and resilience. It is good enough for further analysis.

|

3.3. Measurement Model

- To examine the validity of all constructs, we performed a CFA via AMOS version 20. We used multiple fit indices such as Comparative Fit Index (CFI >. 90), Root-Mean- Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, <.10), Goodness of the fit index (GFI >.90), and chi-square and degree of freedom ratio (X2/df < 3.00) (McDonald & Ho, 2002). The measurement model indicated great fits (e.g. CFI = .987; X2/df =2.197; RMSEA = 0.063; TLI=0.981; GFI=0.957). Therefore, our measurement models are good enough to test the theoretical structural models.

3.4. Structural Equation Modelling Analyses (SEM)

| Figure 1. Conceptual Model |

|

4. Discussions

- Based on the integrating model of the CSM and the TPB, this study aimed to investigate the relationships of three constructs: resilience, self-efficacy, intentions in job searching process. The study also highlights the impacts of one personality characteristic in JS. The findings in the current study are the same as literature relevant to the TPB in employment search, confirmed the CSM model and supported the expected correlations among the determinants of JS intentions. In details, JS self-efficacy was empirically reported to be a reliable precursor of JS intentions. We realized that international students with higher level of self-efficacy reported higher intention to look for jobs and greater likelihood to carry out the searching behaviors. The findings are consistent with other previous studies (Liu, Wang, Liao, & Shi, 2014; Saks et al., 2015) which emphasized that self-efficacy was a dominant construct that determined intention. In this study provided the findings that helped to explain the mixed results regarding to the relationships between these constructs in a different research context.Furthermore, the findings indicated that personality characteristic played a vital role in predicting job seekers’ self-efficacy, intentions. In more details, individuals who were high in resilience level would have higher self-efficacy, intentions for JS. The results were consistent with other research about the relationship of resilience and self-efficacy that suggested that the higher resilience were positively and highly related to higher self-efficacy (Cassidy, 2015; Hamill, 2003). However, although the relationships are positive, resilience only accounted for 4% of the variance in the prediction of JS intention. The findings are somewhat similar to a study by Boudreau, Boswell, Judge, and Bretz Jr (2001), which indicated that a big five factors of personality only explained 0.03 of the variance in predicting JS behaviors. Our finding helped to explain the importance of personality characteristic in predicting self-efficacy in JS and indicated that personality characteristic doesn’t have a great impact on an individual’s intention in JS. In other words, one can have intention and actually perform JS behavior although he/she hardly persists in efforts once facing adversity or failures.

5. Implications

- The findings in the study give us various implications of JS process by investigating the population of Southeast Asian international job seekers in Taiwan. Firstly, academically, it helps to expand our understandings of the TPB and the CSM in the field of career search. Furthermore, the study represents an attempt to understand the TPB from the CSM perspective and makes an important contribution to the career-related research, in general and a Chinese culture context, in particular. Precursors (e.g. resilience) added to the TPB helped to improve the prediction of JS self-efficacy and intentions. Practically, the study gives us guidelines about how to improve JS self-efficacy among SEA students through career related activities and resources. With higher JS self-efficacy they are more likely to have intentions to conduct JS in the host country. Furthermore, the findings indicate that individuals with higher resilience reported higher JSSE. In this regard, besides professional knowledge and skills, practitioners should equip SEA students with resilience training to increase psychological resources in future JS. Secondly, it provides insights into career development process that Taiwan’s international students may go through. SEA students’ JS self-efficacy and intention can be enhanced through developing career exploration and resilience. In addition, it may inform both researchers and practitioners of how resilience plays a role in an international individual’s JS process; by that, JS self-efficacy can significantly be increased. Some suggestions, for instance, are to provide cultural exchange activities/programs or JS platforms for SEA students, which can offer more job related information to international students. With regards to resilience, professional knowledge and skills, practitioners should equip SEA students with resilient training to increase psychological resources in future JS. For instance, some vocational programs with mock interviews should allow international students, in which counselors can design challenges or difficulties for them to try to overcome. Besides, it is important that the international students’ strengths should be underscored as modesty, which may boost them to concentrate on their weaknesses rather than strengths when they show off.

6. Limitations

- Some limitations need to be mentioned in this study. Firstly, since this study only examined Southeast Asian students that account for a part of all international students in Taiwan, with the purpose of increasing the generalizability of research on international students, students from other countries should be included and some comparisons should be made in order to understand the needs as well as challenges among students who are from different countries. Secondly, only self-reported measures were used in this study. Therefore, these subjective perceptions are not the reflection of the real experiences. Thirdly, this study only focused on the JS intentions within the time of 6 months close to graduation. The time constraint provided only partial evidences in the whole JS process and no JS outcomes were investigated. Consequently, future research should include JS outcomes to examine to what extent the antecedents may lead to JS outcomes. Fourthly, the vocational issues of international students should be examined by using other components of the CSM in order that a more comprehensive test of the theory can be done about career search. For instance, sources or antecedents of JS self-efficacy and intention among students should be added into the model as precedent factors by which the level of JS self-efficacy and intention can be increased.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML