-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2018; 8(2): 22-30

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20180802.02

Factor Structure, Reliability and Validity of the Arabic Version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) in a Sample of Saudi Children and Adolescents

Mogeda Elsayed El Keshky

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt

Correspondence to: Mogeda Elsayed El Keshky, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study aims to adapt the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ-CA) in children and adolescents into an Arabic version, and to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Arabic version. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire–Cognitive Reappraisal (ERQ-CA) is a self-report questionnaire based on the process model of emotional regulation, that assesses two emotion regulation (ER) strategies: Cognitive Reappraisal (CR) and Emotional Suppression (ES). The ERQ-CA was examined using a sample of 1250 Saudi-Arabian children and adolescents aged between nine and eighteen years. The results of the study showed good internal consistency (0.785 to 0.754) amongst different age and gender groups, indicating optimum reliability. Test-retest correlations were calculated by administering the ERQ-CA to a subset of sample (n=93) after three weeks. Test-retest reliabilities were 0.78 for cognitive reappraisal and 0.75 for the emotion suppression subscales. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) indicated good support, as the structure demonstrated to be consistent with that of the original questionnaire. Additionally, based on the two-factor model of fit, multi-group CFA showed that the Arabic version of ERQ-CA provides a strict factorial invariance amongst different age groups including equivalent item intercepts, equivalent factor loadings, and equivalent item uniqueness. Additionally, convergent validity showed positive associations between the reappraisal strategy and measures of positive psychological functioning (satisfaction with life). The suppression strategy presented negative associations with the same variable. The study concluded that the Arabic version of the ERQ-CA generally possesses adequate reliability and validity for exploring the use of two ER strategies (CR & ES) during the childhood and adolescence phase.

Keywords: Emotion regulation, Reappraisal, Suppression, Reliability, Psychometric properties, Saudi, Children, Adolescents

Cite this paper: Mogeda Elsayed El Keshky, Factor Structure, Reliability and Validity of the Arabic Version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) in a Sample of Saudi Children and Adolescents, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 8 No. 2, 2018, pp. 22-30. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20180802.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Over the past few decades, there has been increased recognition of the significance of managing or regulating emotions in a socially appropriate and adaptive manner, to encourage children’s healthy psychological development [1, 2]. The inability to manage emotions in a social context has been associated with the development of considerable psychological pathology, including all of AXIS II and more than 50% of Axis I disorders from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [2].Emotion regulation involves the management of both positive and negative emotions, and is affected by intrinsic factors such as emotional cognition, as well as extrinsic factors such as parental support. The processes related to regulating emotions can be either conscious or unconscious and spontaneous or controlled. Such procedures are reliant on the intensity and duration and depend on the intensity, duration and the liability of the emotional experience [3, 4] presented. It is a process-oriented model that describes emotions as multifaceted processes that occur over a period of time. Based on this model, ER strategies have been divided into two classes depending on their temporal relationship with an emotional response. First is the antecedent strategy that occurs before an emotional response happens, while the second type is a response-focused strategy that is employed following the initial emotional response has already occurred [4]. The gross model has identified five categories of emotional strategies namely: situation selection, situation modification, attention deployment, cognitive change and response modulation. Generally, the first four strategies are considered antecedent, and the fifth one, response-focused [5].According to John & Cross [6], prior research has operationalized two ER strategies within this model. These strategies are: 1) Cognitive Reappraisal (CR), which denotes a cognitive change strategy that involves altering a potentially emotion stimulating situation, in a way that the emotional impact is changed; 2) Expressive Suppression (ES) which is a type of response modulation strategy that involves inhibiting the current emotion expressive behavior. The impetus for the implementation of these two strategies has been cited as they both represent antecedent-focused and response–focused strategies respectively, and they are the most used on a day to day basis [6, 2].Developmental research relating to emotional regulation has continued to primarily focus on infancy and early childhood periods, as these age periods represent a time when social and personal forces act together to lay the foundation for the individual differences observed in emotional regulation in later life [7]. It is uncontested that this research is of foremost importance, but it is also observed that other crucial periods of development, late childhood and adolescence, have remained neglected during the research [8]. These time periods are critical as they represent the major acquisition of social, cognitive and emotional skills and development of autonomy of individuals [9]. Middle childhood and adolescence mark a rapid transformation in emotional response, and adolescent experiences tend to be more frequent and intense emotions in comparison to young children and adults. Hence, prevalence of a range of psychological and mental disorders increases significantly during the adolescence period [10].In 2003, Gross and John [5] developed the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ). It is a self-report questionnaire which measures CR and ES in adults and assesses the individual differences in CR and ES. The evaluation for internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire showed Cronbach’s α values of 7.82 (mean 0.79) for CR and 0.76 (mean 0.73) for ES, for four sets of samples. Test–retest reliability across three months was 0.69 for both CR and ES. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) showed good support for this underlying two-scale structure [5].Other versions of ERQ were developed by later researchers for children and adolescents by using appropriate psychometric procedures. These versions included the Italian version of ERQ (ERQ-I) [11], the Australian version of the ERQ for Children and Adolescents (ERQ-CA) [2] and a Chinese version for children [12]. Internal consistency depicted by Cronbach’s α values showed satisfactory values ranging from 0.84 for CR to 0.72 for ES in the Italian version [11], and from 0.83 CR to 0.75 E) for the Australian version questionnaire [2]. The temporal stabilities of ERQ-I across two months were shown to be 0.67 for CR and 0.71 for ES [11], however, for ERQ-CA, temporal stability was found to be moderately sized for both ES and CR factors [2]. The interclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.37 to 0.47 (for the 10 to 13 and 16 to 18-year-old groups respectively) for the CR scale. For the ES scale, coefficients ranged between 0.40 (for the 10 to 12-year-old group) and 0.63 (for the 16 to 18-year-old group) [2]. Numerous studies have also established the validity of ERQ by comparing it with other personality measures such as the Children’s Depression Inventory, NEO Five-Factor Inventory and Negative Affect Schedule [11, 2]. Through previous studies, several associations established that CR has a negative correlation with Neuroticism, while ES negatively correlated with Extraversion (cf. [11, 5]). Moreover, CR is shown to be a better predictor of psychological functioning and ES of psychological distress [13]. On the depression scale CR correlated negatively, while ES correlated positively with depression symptoms [5]. Furthermore, ERQ for adults and ERQ-CA have also depicted adequate convergent validity [5, 2, 6].The percentage of adolescents between the ages of 10-19 years in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) equates to approximately 20% of its population [14]. “Jeeluna” (Arabic for “Our Generation”) is a national adolescence health study. It reported that 14% and 6.7% of adolescents showed depression and anxiety symptoms respectively. Twenty-five percent admitted exposure to bullying in the preceding month and 20% were involved in physical violence either at school or in their community in the previous year [15].To the best of our knowledge, there has been very limited research efforts have displayed that the ERQ-CA is age and gender invariant. One study from China [12] studied the effect of age and gender, and concluded that in spite the difference in age and gender, the participants used the same frame of reference when using the ERQ-CA for rating their ER strategies [12]. The effectiveness of any instrument or questionnaire relies primarily upon on its psychometric properties, and it would require reliability and validity testing before applying them across different populations and contexts [16]. Saudi Arabia is a country with distinct cultural influences, and some previous studies have studied and found cross-culture variations in ER strategies [17].Thus, the present study was undertaken to assess the reliability and validity of ERQ-CA in the Saudi Arabian population of children and adolescents given the distinct culture. Further objectives of the study aimed to evaluate the internal consistency of the ERQ total and subscale scores across gender and age, and to evaluate the gender and age differences for total ERQ. Using the CFA and Structural Equation Models (SEM) were also utilised to verify whether the two-factor structure of the original ERQ questionnaire was a good fit to the population of Saudi-Arabian children and adolescents, and to compare it across children, adolescents taking into consideration both male and female participants.

2. Method

- For this study, children and adolescents living in one of the major cities, Jeddah, situated in the west of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were included. A total of 1250 student aged between 9 to18 years were randomly selected to participate from twelve basic and elementary schools. All participating schools belonged to metropolitan regions, had single gender populations and represented diverse socio-economic backgrounds. Of the initial selected 1250 students, 29 students were excluded as their questionnaires were incomplete. Thus, the final sample consisted of 1221 participants (mean age = 14.17 years, SD = 2.86). To enable their participation, written consent was sought from the relevant school boards and parents, while the students agreed to participate and complete the ERQ-CA. In addition to ERQ, students also completed SWLS (Satisfaction with life scale) during their regular classroom hours. Furthermore, a randomly selected subgroup of sample (n = 93) undertook the ERQ again three weeks later to measure the test-retest reliability. To ensure consistent data collection across all schools, trained research assistants administered questionnaires to students in their respective classrooms in groups. Initial items were read aloud from the questionnaire, and the research assistants were available for answering any queries throughout completion of the form.The Arabic version of the ERQ-CA was developed using a back-translation procedure. Two bilingual Arabic-English psychologists translated the English version of the ERQ-CA into Arabic. Following this, another Arabic-English bilingual psychologist translated the Arabic-translated questionnaire back into English. Inconsistencies that emerged from the back-translation procedure were discussed, and modifications to the Arabic translation of the ERQ-CA were conducted.

3. Measures

3.1. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire – Children and Adolescents (ERQ-CA)

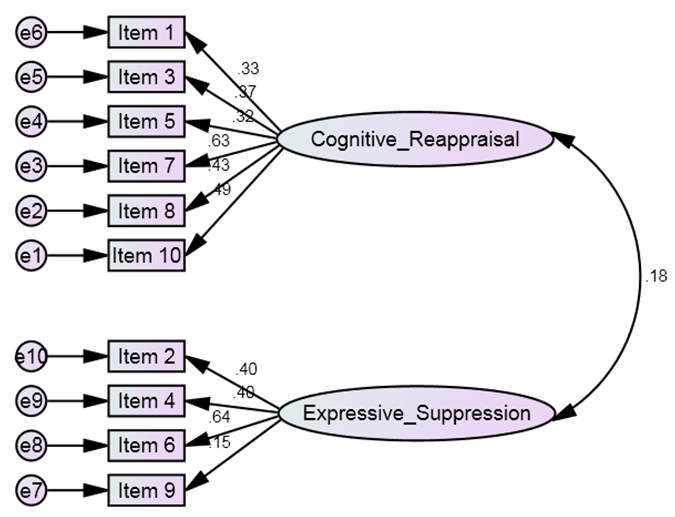

- The ERQ is a ten-item self-report measure that assesses individual differences in the use of two different emotion regulation strategies, namely, Cognitive Reappraisal (CR), and Expressive Suppression (ES). The items are rated in a 5-point Likert-type response scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The CR subscale consists of six items (1, 3, 5, 7, 8 and 10). The ES subscale consists of four items (2, 4, 6 and 9). The scores were based on the total of all items, for each subscale. There were no reverse items. The scores on each subscale range from 6 to 42 (CR) and from 4 to 28 (ES). Higher scores on each subscale mean greater use of the correspondent strategy [5].

3.2. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

- This is a 5-item scale developed to assess the global cognitive judgment of the respondent’s life satisfaction. Respondents indicate their agreement or disagreement with each of the five items using a 7-point Likert scale, where responses range from 7 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree [18].

4. Statistical Analysis

- The survey data was analysed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. First, the descriptive statistics of the data was analysed to see how the data was distributed. Then reliability, validity and factor structure analysis were conducted. The data was assessed for internal consistency of the ERQ total and subscale scores, using Cronbach's alpha coefficients across gender (males and females) and age groups (children and adolescents). Multivariate analyses of variance (MANCOVA) and effect size statistics were used to evaluate gender and age differences for total (ERQ) and MANOVA tests, and to examine gender and age differences separately for both emotion regulation strategies (reappraisal and suppression). Factor Structure of the ERQ-CA was obtained via Exploratory Factor Analysis, with CFA and Structural Equation Models (SEM) used to verify whether the two-factor structure of the original (ERQ) questionnaire was a good fit to the population of children and adolescents. This was also used to assess the differences of factor structure across gender and age groups, and to compare fit across children and adolescents, and across male and female participants. Strict confirmatory factor analysis was performed to find a fit model for the whole sample. The test-retest reliability coefficient was also measured to assess the reliability of the ERQ scores over time. Lastly, we performed Pearson correlations between the QRE-CA subscales and the Satisfaction with Life Scale to test the convergent validity.

5. Results

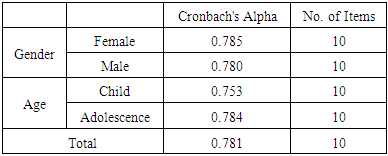

- The internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach's Alpha coefficients across gender and age categories. The findings indicated that all the items have adequate internal consistency overall and for every category including age and gender. All the Alpha values appeared between 0.753 to 0.785 and are greater than the suggested minimum threshold of 0.7. This is shown in Table 1.

|

|

5.1. MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance)

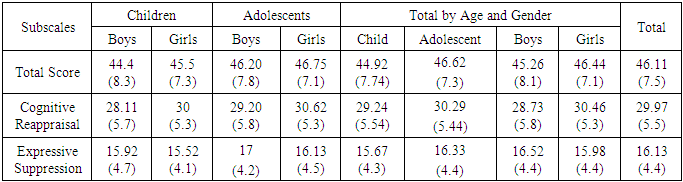

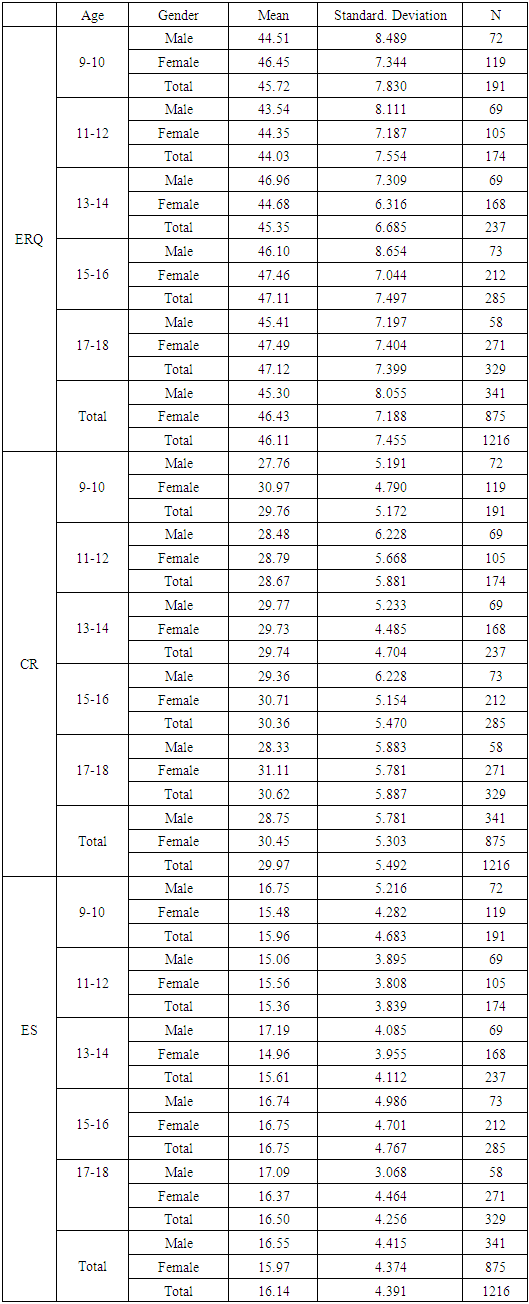

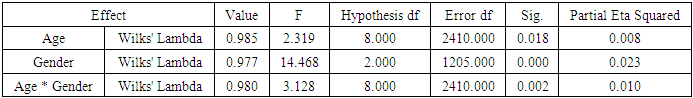

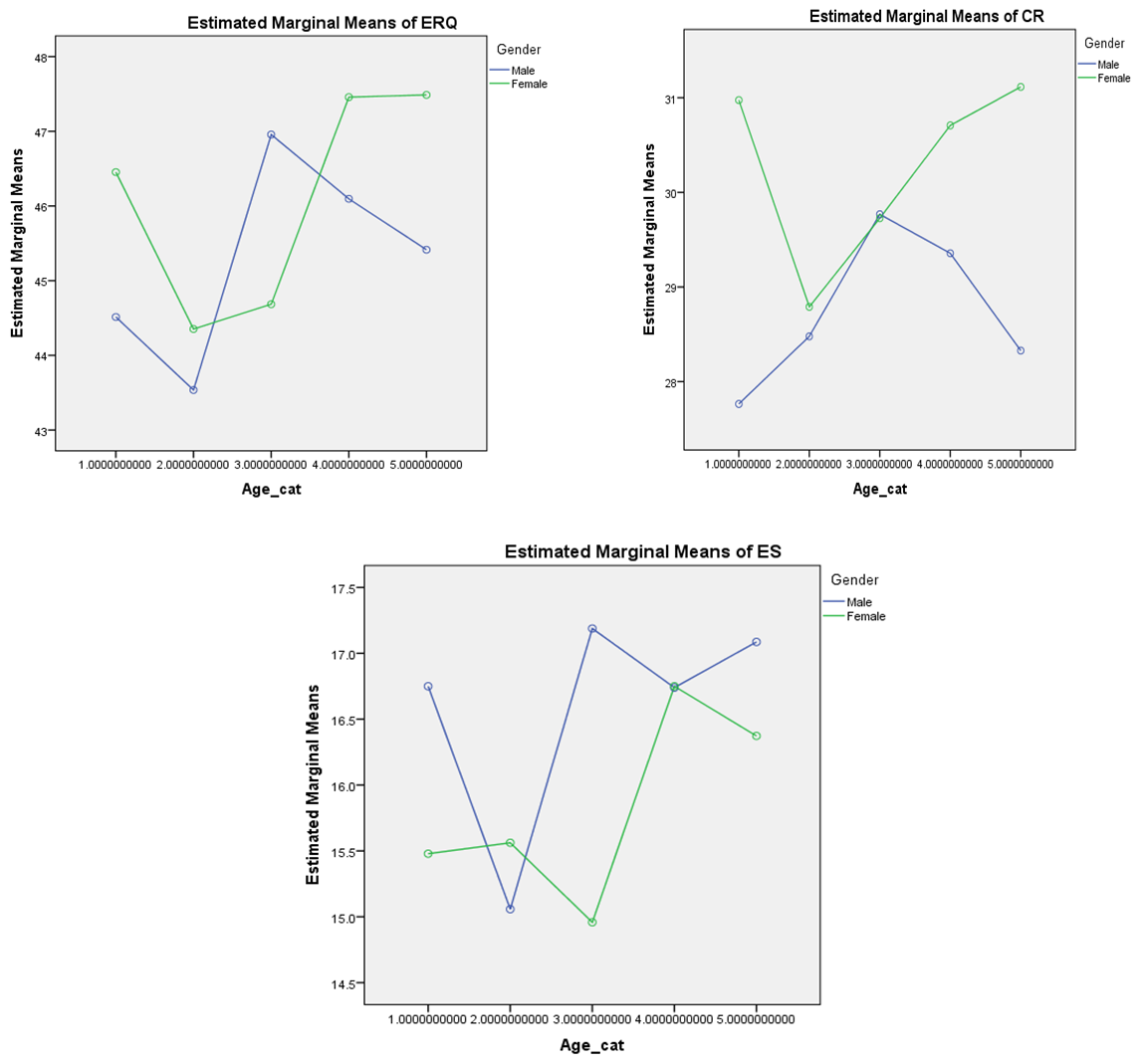

- Multivariate Analysis of Variance has been conducted to illustrate how gender and age differences impact Cognitive Reappraisal (CR), Expressive Suppression (ES) and Total Emotion Regulation (ERQ). Table 3 shows the mean values for ERQ, CR and ES for various categories and gender. It can be seen that among the participants aged 9-10 years, females have a higher score for ERQ than their male counterparts. A similar situation can be seen for participants between the ages of 11 and 12 as well. It can also be seen that the 11-12 age group had a higher ERQ score than the 9-10 age group.

|

|

| Figure 1. Influence of age and gender on Cognitive Reappraisal (CR), Expressive Suppression (ES) and Total emotion regulation (ERQ) |

5.2. Factor Structure of the SEQ-C Obtained via Exploratory Factor Analysis

- The factorial structures of the ERQ-CA were examined through CFA. EFA to illustrate the factor structure for SEQ-C. The KMO and Bartlett’s test indicates that there are just enough adequate samples to conduct the analysis, due to the KMO score being marginally acceptable.

5.3. Verification of Two Factor Structure Using Structure Equation Modelling

- Structural Equation Modelling has been conducted to verify the two-factor structure explaining emotion regulation in children and adolescents. The respective items have been used to construct the latent factors (Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression) using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). After that, the latent factors have been directly used to measure SEQ-C (from CFA to SEM). 2 shows this.

5.4. Model Fit

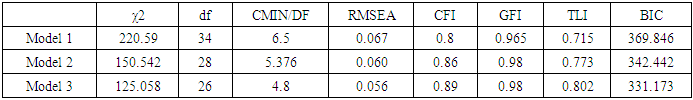

- A comparison between the current model indices and the baseline was conducted in order to assess the fit of the model.Table 5 shows three models. Using the modification indices, the models have been improved to provide a better fit.

|

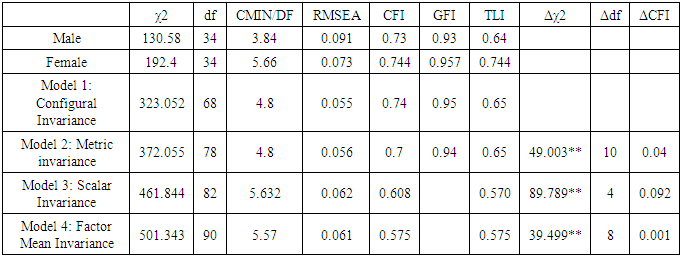

5.5. Multi-group Analysis of Model for Gender Difference

- Multi-group analysis has been conducted on the model to illustrate whether there are any differences at the model level in terms of gender. In Table 6, model fit indices indicate that for the female group, a better fit model has been achieved compared to the males (as the RMSEA is smaller). Multi-group invariance analysis was conducted with four model types.

| Figure 2. Path diagram for two factor CFA structure for SEQ-C |

|

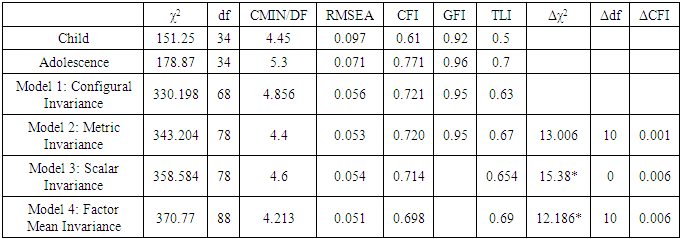

5.6. Multi-group Analysis of Model for Age Difference

- Similar analysis was applied to explore any differences in the factor structure across age (children and adolescents). The model fit indices in Table 7 showed that a better fit model could be achieved for the adolescence group in comparison to the child group (as the RMSEA is smaller).

|

5.7. Convergent Validity

- As expected, we found significant positive associations between reappraisal and satisfaction with life (rs = 0.54, ps/0.001), meaning that a greater use of reappraisal strategy is associated with higher levels of satisfaction with life. On the other hand, we found significant negative associations between suppression and life satisfaction (rs = -0.26, ps/0.001).

6. Discussion

- This study aimed to validate the Arabic version of the ERQ-CA, and to provide information on the age and gender differences, adaptation procedures and psychometric properties of this version, by using a large sample of Saudi Arabian children and adolescents. Translation for the study was conducted using the backward procedure. In the analysis, an item correlation test was applied to assess whether the response to a given item could be included in the set being averaged. A cut point of 0.30 was set, indicating that the corresponding item correlated well with the scale. All items in our sample showed a correlation value higher than 0.30, therefore all items should be retained in our version.The internal consistencies measured across all groups (0.785-0.781) were similar to those found in other psychometric evaluation studies of ER questionnaires [2, 12, 21]. Cronbach’s α value ranged from 0.785 and 0.780 for males and females respectively, and 0.753 and 0.784 for children and adolescents. The test-retest reliability, was found as 0.787 and 0.754 for cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression subscales respectively, exceeding the set criterion of 0.70 set by Nunnally & Bernstein [22]. Our Arabic version of ERQ-CA presented a better reliability co-efficiency in comparison to other versions, including an Italian version of ERQ [11] which indicated 0.67 reliability co-efficient for the cognitive reappraisal (CR) and 0.71 for the Emotional suppression (ES). MANOVA analysis showed that age and gender independently, and their interaction, significantly influenced the Cognitive Reappraisal (CR), Expressive Suppression (ES) and Total Emotion Regulation (ERQ). The CFA model applied to the children and adolescent subgroups showed a good fit, whereas various indices supporting the two-factor model. These results were consistent with the observations made in similar earlier studies [12, 5, 2]. The sufficiency of the scale was validated [21] as CFA results showed that items loaded on both factors (ES and CR) were above 0.30.The findings indicate that members from different age groups utilise the same frame of reference when rating their ER strategies. However, chi-square differences across genders were found to be statistically significant, and thus can change the model structure. This finding is contrary to prior findings from the Turkish version [21], the Chinese version [12] and Melka et al.’s [23] study. Such gender differences can be explained by the cultural influence on emotions and how that can regulate gender-specific emotional strategies [28]. Sala et al., [23] carried out a study to evaluate the measurement invariance in undergraduate students of two European countries (Italian and German), and the results showed that there was a measurement invariance in male and female undergraduate students. However, in a study [24], findings revealed that this factor structure of the ERQ was not supported by either the Australian or United Kingdom non-student samples. Other studies have also recognised differences in the use and results of emotion regulation responses as emotional suppression, and reappraisal across different cultural backgrounds [5, 26, 27]. Thus, in our study, cultural influences might be responsible for gender differences, and a better model fit may be achieved by further revising the ERQ to ensure that it is invariant across the subgroup samples including both gender and age.Random sampling and inclusion of a wider age group inclusive of children and adolescents is a strength of our study, but the selecting a sample from schools only excluded children and adolescents in the community; and therefore, affecting the generalizability of the instrument. Secondly, common method biases were also unavoidable due to the measure in this study being self-reported instruments. Therefore, for future studies discriminant validity must be established, and the above-mentioned weaknesses must be addressed.In conclusion, the present study of the psychometric evaluation of the Arabic version of ERQ-CA, a revised version of the ERQ, for use in children and adolescents was able to demonstrate that the ERQ–CA is a valid and reliable instrument for the evaluation of the of two ER strategies (CR & ES). The present findings reveal that the ERQ–CA possesses adequate internal consistency and reliability over a period of time, construct validity that is invariant across age, and adequate convergent validity. Accordingly, these findings support the use of this revised instrument with the child and adolescent population and pave way for future studies that include Saudi-Arabian youth.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML