-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2017; 7(6): 152-159

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170706.02

The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Community Language Teaching: A Case Study of Iranian Intermediate L2 Learners

Hassan Banaruee, Hooshang Khoshsima, Omid Khatin-Zadeh

Chabahar Maritime University, Chabahar, Iran

Correspondence to: Hooshang Khoshsima, Chabahar Maritime University, Chabahar, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study aimed to explore the differences between high and low-EQ scorers in learning an L2. To achieve this objective, a group of 30 intermediate learners attended a course in which community language teaching was used to teach speaking skills to the learners. Half of the participants had high EQs and the other half had low EQs. Speaking ability of these participants was checked by a pre-test before treatment and a post-test after treatment. Results of these tests showed that high-EQ L2 learners benefit more from those courses in which community language teaching is used to teach speaking skills to learners. It is suggested that being more aware of the feelings of themselves and others can be an influential factor in the success of those L2 learners who are taught by community language teaching. This is in agreement with humanistic approaches to language teaching that emphasize the role of emotional factors in the process of language development. The findings of this study suggest further lines of investigation through which the impact of EQ on L2 acquisition can be explored.

Keywords: Emotional intelligence, Community language teaching, EQ

Cite this paper: Hassan Banaruee, Hooshang Khoshsima, Omid Khatin-Zadeh, The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Community Language Teaching: A Case Study of Iranian Intermediate L2 Learners, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 6, 2017, pp. 152-159. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170706.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction and Literature Review

- This study aimed to investigate the relationship between emotional intelligence and degree of achievement among Iranian L2 learners. Emotional intelligence is one of the topics that have attracted a lot of attention among researchers working in various fields, including psychology and language teaching. The relationship between emotional intelligence and performance in various cognitive and linguistic abilities has been a topic of interest for researchers. This study focused on the speaking ability of L2 learners who attended a course in which community language teaching was used.

1.1. Emotional Intelligence

- Emotional intelligence has been defined as the awareness of an individual of his/her feelings and other’s feelings and the ability to manage them (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000). Emotional quotient (EQ) is the ability to recognize emotions, to access and generate them in order to aid thought, to comprehend emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively control them to advance emotional and intellectual growth (ibid). Our emotional intelligence helps us to evaluate our own and others’ emotions, express feelings appropriately, and regulate emotions in order to achieve a goal (Ghabanchi & Rastegar, 2014; Salovey & Mayer, 1990).Thorndike (1920) defines EQ as the ability to understand and manage others and to act intelligently. EQ has been defined by using different terms by many researchers in the field. The definitions have some commonalities as well as some differences. Emotional intelligence has been described as the ability to recognize, understand, and adjust emotions (Salovey & Mayer, 1990; Schutte, Malouff, Hall, Haggerty, Cooper, Golden, & Dornheim, 1998). Emotional intelligence reflects abilities to combine intelligence, empathy and emotions to enhance thought and understanding of interpersonal dynamics. The term "emotional intelligence" initially appeared in two articles. Leuner (1966) was one of the first researchers who used the term in academic writings. Gardner (1983) used the term in subjects related to intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence. EQ has been discussed in the literature of the field for a long time (for example, Greenspan, 1989; Leuner, 1966), although it was in 1990 that the construct was introduced in its current form (Salovey & Mayer, 1990).Mayer, Salovey, Caruso (2000) developed a way for scientifically measuring people's emotions. They said that a high EQ individual can better perceive emotions, use them in thought, understand their meanings, and manage emotions, than others. They added that solving emotional problems likely requires less cognitive effort for this individual.

1.2. Community Language Teaching

- According to Moskowitz (1978), community language teaching refers to a group of methods that are called humanistic techniques. Moskowitz adds that humanistic techniques blend what the language learner feels with what s/he thinks. According to Richards and Rodgers (2001), humanistic techniques engage the whole person, including emotions, linguistic knowledge, and behavioral skills. La Forge (1983) says that in an L2 classroom, learners’ intimacy deepens as the class becomes a community of language learners. The desire to develop intimacy with other learners pushes them forward in the process of learning (ibid). Community language learning is holistic; that is, it involves cognitive and affective factors (Curran, 1972). That is why it is called whole-person learning. In this method of language teaching, learning takes place in a communicative context (ibid).Having administered a pre-test before treatment and a post-test after treatment, this study intended to examine the role of emotional intelligence in the growth of speaking ability in a course that community language teaching was used. To this end, a group of high EQ learners and a group of low-EQ learners attended a two-month course of speaking. In this way, the study tried to answer the following questions:1. Is there any significant relationship between emotional intelligence and growth of speaking ability in a class that is taught by techniques of community language teaching?2. If there is a significant difference between high-EQ learners and low-EQ learners in this course, how can this difference be explained?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

- Participants of the study were a group of 30 undergraduate students in the Department of English at Chabahar Maritime University. They were between 19 and 23 years old. This group consisted of 19 males and 11 females. A sample of Michigan TOEFL test was used to determine their proficiency in English. Based on the results of this test, only those students who were at intermediate level of English proficiency were selected for the main part of the study.

2.2. Instruments

- Before conducting the main part of the study, a sample of Michigan TOEFL test was used to select those students who were at the intermediate level of proficiency in English. Also, the Persian translation of Bar-On-EI test was used to measure EQ of the participants (See the Apendix). The validity and reliability of Persian translation of this test have been confirmed by Dehshiri (2003). This test included 133 items. Participants were expected to answer the items on the basis of a Likert scale that consisted of 5 options, ranging from ‘Never” (1 score) to ‘Always’ (5 scores). The sum of these scores for each participant was taken as EQ score of that participant. Therefore, the minimum possible score was 0 and the maximum possible score was 665. In addition to these, a voice recorder was used to record the voice of the participants during speaking test for re-checking and assigning scores. Two raters listened to these records and assigned scores independently.

2.3. Procedure

- First, a sample of Michigan TOEFL test was administered among a large group of undergraduate students in the Department of English of Chabahar Maritime University. Only those who were at intermediate level of English proficiency were selected for the main part of the study. Then, Bar-On-EI test was used to select 15 high-EQ learners (with a score of higher than 340) and 15 low-EQ learners (with a score of lower than 340). Before receiving treatment, participants attended a pre-test of speaking. This test was administered by the researchers of the study. Then, they attended a community language teaching course of speaking for two months. All participants attended the same class that was taught by one of the researchers of the study. After treatment period, a post-test of speaking was administered to examine the progress of the participants.

2.4. Data Analysis

- In the pre-test, each participant received two scores by two independent raters. Pearson coefficient was obtained to ensure inter-rater reliability. This value was 0.83, which was completely acceptable. For each participant, the mean of the two scores was taken as his/her score on the pre-test. Then, the data of post-test were analyzed. Inter-rater reliability of this test was checked by obtaining Pearson coefficient. This value was 0.79, which was an acceptable value. In the next stage of data analysis, two paired T-tests and two unpaired T-tests were run. The first paired T-test was used to compare the scores of high-EQ participants in the pre-test and post-test. The second paired T-test was used to compare the scores of low-EQ participants in the pre-test and post-test. The aim of the first unpaired T-test was to compare the scores of high-EQ participants with the scores of low-EQ participants in the pre-test. The aim of the second unpaired T-test was to compare the scores of high-EQ participants with the scores of low-EQ participants in the post-test.

3. Results

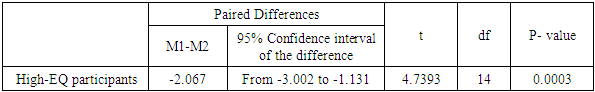

- As was mentioned, the aim of the first paired T-test was to compare the scores of high-EQ participants in the pre-test and post-test. Results of this T-test have been given in Table 1.

|

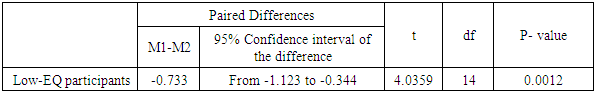

|

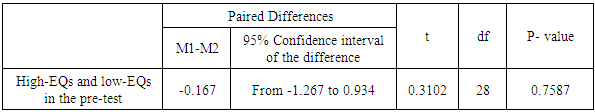

|

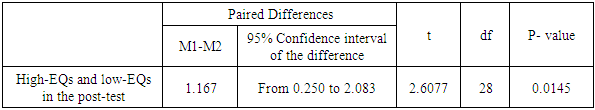

|

4. Discussions

- As was mentioned in the results, both high-EQ and low-EQ participants benefitted from community language teaching and made a significant progress throughout treatment period. However, degree of progress among high-EQ participants was significantly higher than low-EQ participants. The question that is raised here is that why high-EQ L2 learners highly benefit from community language teaching. To answer this question, we have to look at the nature of community language teaching and the practices that are used in a class that is taught by communicative activities. Communicative practices are highly reliant on the relationships that are created in the classroom as a mini-society. In this small society, L2 learners develop their linguistic ability through interaction with each other. There is no doubt that emotions are an important dimension of any relationship that is developed among human beings, and the relationships that are formed in an L2 classroom are not an exception. Therefore, it might be suggested that high-EQ L2 learners benefit more in a class that is taught by community language teaching because they are more successful in understanding others and cooperating with others. This puts them in a stronger position in those linguistic activities that are reliant on the relationships among L2 learners in a small society. Being more aware of other’s feelings can help high-EQ L2 learners to overcome affective hurdles that might prevent linguistic interactions among learners in the classroom. In fact, this can be a strong point for high-EQ learners and an effective tool for facilitating interactions in the classroom.Any interaction in language classroom involves at least two parties. The high emotional ability of one of the involved parties could have a positive psychological impact on other parties. This positive impact could strengthen relationships. In other words, the positive psychological impact has a bilateral nature. In the interactions that take place among learners, when one party sends a signal indicating that s/he understands others, the other learners become more motivated to participate in communicative activities. This can be crucially important for the progress of learners in a class that is taught by communicative methods of language teaching. In such an environment, learners can easily agree on a common goal and cooperate with each other to achieve that shared goal. This is psychologically very important and can function as a major source of motivation for learners. In fact, a small community in which learners have close bonds and share a common goal is the right place for the development of linguistic skills. In this community, learners do their best to communicate with each other and send their messages across through the networks of community.The role of emotions has been emphasized by humanistic approaches to language learning and language acquisition. Humanistic approaches take this view that the process of linguistic development involves the whole dimensions of human life. Among these dimensions, feelings are crucially important because they could be a major force of motivation for pushing learners forward. On the other hand, negative feelings could be a hurdle for learners. In both cases, having a high EQ can be a great help for learners. In the first case (positive feelings), learners become aware that things are going in the right direction and they can even facilitate this process. In the latter case (negative feelings), they can employ proper strategies to remove emotional hurdles that could disrupt the processes of language learning and language acquisition in the classroom. All of these objectives can be achieved if L2 learners have a high degree of awareness of their own feelings and those of others in the context of classroom as a small community.

5. Conclusions

- Results obtained in a course that community language teaching is used are highly dependent on the strength of social bonds that are formed throughout the course. There are a number of factors that might influence these bonds. Among these factors, emotional ones play a crucial role. Results obtained in this study indicated that those L2 learners who have a high EQ are more successful in such courses. Even the presence of these learners in a class that is taught by community language teaching can benefit other L2 learners. This is in agreement with the position that is taken by humanistic approaches to language teaching. Therefore, it is suggested that EQ of L2 learners be taken into consideration in the planning for those courses in which community language teaching is used. In this way, better results can be achieved. It seems that a combination of high-EQ and low-EQ L2 learners in the classroom is the optimal way that can benefit various groups of learners, including those who have low EQs. The final point that must not be ignored is the role of cultural factors. The way that L2 learners interact with each other in a class that is taught by community language teaching can be very different from culture to culture. This is an issue that must seriously be taken into account in any planning for such courses.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML