-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2017; 7(2): 61-65

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170702.03

Neurobehavioural Assessment of Some Artemisinin Combination Therapies on Suppressive Malaria Model

Koofreh G. Davies1, Innocent A. Edagha2

1Department of Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Uyo, Nigeria

2Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Uyo, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Koofreh G. Davies, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Uyo, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study was designed to examine the effects of Artemisinin Combination Therapy on anxiety and cognition using the suppressive malaria model. Twenty five mice were divided into five groups. Group 1 served as the control while groups 2 to 5 served as the experimental groups and were passaged with Plasmodiumbergheiberghei. While groups 3 to 5 were treated respectively with Artesunate/Amodiaquine, Dihydroartemisinin /Piperaquine and Arthemeter/Lumefantrine, group 2 was not given any drug. T maze was used for cognition test while Light and Dark box was used for anxiety test. Results showed that the time spent in the reference arm of the T- maze was not significantly different between the control group and any of the experimental groups in, indicating that there was no memory impairment. In light and dark box, the animals in groups 3 to 5 spent greater time in the dark chamber compared to the control group, suggesting increase anxiety. In conclusion, this study shows that mild malaria infection does not impair cognitive function. However, the Artemisinin Combination Therapy (ACT) at clinical doses appears to cause anxiety.

Keywords: Malaria, Artemisinin Combination Therapy, Anxiety, Cognition

Cite this paper: Koofreh G. Davies, Innocent A. Edagha, Neurobehavioural Assessment of Some Artemisinin Combination Therapies on Suppressive Malaria Model, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 61-65. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170702.03.

Article Outline

1. Background of the Study

- Around the world, the malaria situation is serious and getting worse. It is an often fatal disease caused by the malaria parasite; Plasmodium (P) falciparum, Plasmodium Vivax, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium Knowlesi [1]. Of all these, P. Falciparum is the most life threatening, accounting for majority of malaria deaths in developing world. The malaria disease cycle is dependent on transmission between people by mosquitoes. A single bite from an infected mosquito can lead to malaria. Following the bite, the parasite travels to the liver within 30 minutes and starts to reproduce rapidly [2]. This process can take between 5 and 16 days. However some parasites lie dormant in the liver and may only become active years later. The parasites travel from liver to blood stream, enter the red blood cells and continue to reproduce. The red blood cells eventually rupture, releasing more parasites into the bloodstream to infect other red blood cells. This repeating cycle depletes the body of oxygen and coincides with the onset of fever and chills. It is both the direct action of the parasite and the body’s response to the parasitic infection that lead to the symptoms of malaria [3]. The most severe form is caused by P. Falciparum with variable clinical features including fever, chills, headache, muscular aching, and weakness, vomiting, cough, diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Other symptoms related to organ failure may supervene, such as acute renal failure, pulmonary oedema, generalised convulsions, circulatory collapse, followed by coma and death. The initial symptoms, which may be mild, may not be easy to recognise as being due to malaria [4]. It is important that the possibility of falciparum malaria is considered in all cases of unexplained fever starting at any time between 7 days after the first possible exposure to malaria and 3 months (or rarely later) after the last possible exposure. Any individual who experiences a fever in this interval should immediately seek diagnosis and effective treatment, and inform medical personnel of the possible exposure to malaria infection. Falciparum malaria may be fatal if treatment is delayed beyond 24 hours after the onset of the clinical symptoms. Young children, pregnant women, people who are immuno-suppressed and elderly travellers are particularly at risk of severe disease. Malaria, particularly P. Falciparum in non-immune pregnant travellers increases the risk of maternal death, miscarriage, still birth and neonatal death.There were a lot of concerns regarding the use of artemisinins following reports that administration of high and prolonged doses of artemisinins in laboratory animals cause neurotoxicity [5]. However, many other studies have also shown that artemisinins are very safe when administered at clinical dose regimen [6]. In some earlier, studies we also demonstrated that artesunate and artemether at clinical doses did not impair neurobehavioural parameters in laboratory animals [7, 8]. Generally, there is lack of data on neurological or neurobehavioural effects of artemisinin combination drugs in healthy subjects in the first instance and then in the presence of malaria parasite. Thus neurobehaviour of animals treated with Artemesinin Combination Therapy (ACT) have not been established. So, this research work is intended to fill in the gap and satisfy all curiosity in that aspect.The aim of this study is to compare the effects of ACTs namely Arthemeter/Lumefantrine, Artesunate/Amodiaquine, Dihydroartemisinin/Piperaquine on anxiety and cognitive activities in suppressive murine malaria model.

2. Materials and Methods

- Animal CareAdult albino mice were housed in standard cages. Not more than five mice were put in each cage, and they were grouped according to their weight to. They were fed with pellet feed (vital feed and flour mill limited, Edo, Nigeria). All animals were housed in a cross ventilated room (temp 22+2.5; humidity 65+5% and 12h light/12h dark cycle). The animal beddings and water were changed on alternate days. Acquisition of Donor MiceParasite Plasmodium berghei was obtained from the animal house of Basic Medical Science University of Uyo, Uyo. A standard inoculum of 1x107 of parasitized erythrocytes from a donor mouse in volumes of 0.4ml was used to infect the experimental animal intra-peritoneally.Experimental DesignGroup I served as control and were neither infected nor treated. Group II were infected with Plasmodium berghei berghei (Pbb) but were not treated. Group III were infected and treated with Camosunate® (Artesunate/Amodiaquine).Group IV were infected and treated with P-Alaxin® (Dihydroartemisinin/Piperaquine). Group II were infected and treated with Coartem® (Arthemeter/Lumefantrine). Drug PreparationThe drugs were prepared differently as follows; 20mg of arthemeter/ lumefantrine was dissolved in 50ml of distilled water to produce a stock solution of 0.4mg/ml. 40mg of artesunate/amodiaquine was dissolved in 40ml of distilled water to produce a stock solution of 1mg/ml. 100mg of dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine was dissolved in 100ml of distilled water to produce a stock solution of 1mg/ml. Drug Administration The drugs were administered with oral cannula exactly 3 hours after infection. All the treated animals received 5mg/kgbwt of their respective drugs while the untreated animals were given 5ml/kg of normal saline.Anxiety and Cognition Tests For anxiety test, dark and light box was used, while T-maze was used for cognitive test. Light-Dark Box (LDB)Test is a popular animal model used in pharmacology/physiology to assay unconditioned anxiety responses in rodents [9]. It has two compartments. The light compartment is 2/3 of the total box and is brightly lit. The dark compartment is 1/3 of the total box and is dark. A door of 7cm connects the two compartments [10]. Rodents prefer darker areas over brighter areas. However, when introduced to a novel environment, they tend to explore. These two conflicting emotions lead to observable anxiety like symptoms [9]. The LDB does not require habituation. No food or water is deprived and only natural stressors such as light are used [10]. Procedures for Light-Dark BoxRodents are placed in the light compartment of the apparatus and are allowed to move around. Typically rodents will move around the periphery of the compartment until they find the door. This process can take between 7-12 seconds. All four paws must be placed into the opposite chamber to be considered an entry [11].T-MazeIn behavioural science, a T-maze is a simple maze used in animal cognition experiments [12]. It is shaped like the letter T, providing the rodent with a straight forward choice. T-mazes are used to study how the rodents function with memory and spatial learning through applying various stimuli. The T-maze is made up of the base, the left arm and the right arm. Habituation is involved, and then a reward is introduced. The reward can be feed, a scent or a novel object. Normally, the animal will spend more time in the arm where the new object is introduced. This experiment can also help in knowing the rodent’s preferences example could be the rodent’s food preference. Rodents are introduced at the base of the T-maze. Before introducing the animal, the two objects of the same colour are placed one in the left arm and one in the right arm. The animal will spend almost equal time in both arms thus familiarizing itself with the object. This process is called habituation [12]. After 3 minutes, the animal is removed and one of the objects is removed and replaced with an object of different colour. Normally, the animal should spend more time with the new object. Statistical AnalysisData were expressed as mean + standard error of mean (SEM). The data were analysed using Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the post hoc test (Student-Newman Keuls) for comparison. Values of p<0.05 were regarded as significant.

3. Results

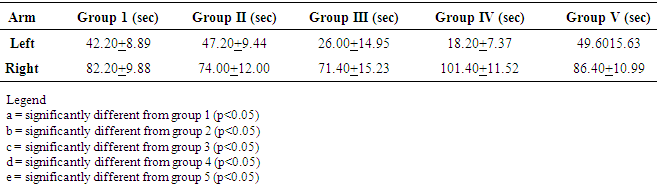

- T-MazeThe time spent in the left and right (referenced) arm of the T maze during the memory test is shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the control and the experimental groups.

|

|

4. Discussion

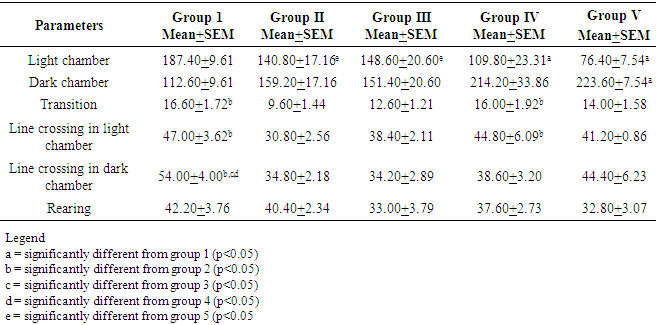

- This is about the first neurobehavioural study to evaluate the Artemisinin Combination Therapy (ACT) in suppressive malaria model. Two behavioural tests, namely T maze and Light/Dark transistion box were employed in this study. T-maze was used to study short-term memory while the light dark transition box was used to study anxiety. As shown in the results, there was no significant difference between the control group and any of the experimental groups in the time spent in the reference arm of the T-maze. The finding is not surprising considering the fact that the experiment was carried out just 3 days after 3 days post infection of the mice. Previous studies demonstrated memory impairment or deficit 7days post infection [13]. These authors used novel objects recognition test to establish their findings. Their study also revealed that cognitive dysfunction correlated with haemorrhage and inflammation involving many areas in the brain including cortex, thalamus and hippocampus [13]. These brain regions are known for memory processing and consolidation. So, as mentioned above, there was no memory impairment in any of the groups including the treated groups. The lack of significant difference between treated groups and control groups also indicates that the Artemisinin Combination Therapy at clinical dosage did not have any negative effect on memory within 3 days. Some studies have reported previously that ACTs at clinical dosage are well tolerated and safe [14]. On the contrary, our findings did not support an earlier work by Onalapoolakunle et al. (2013), which showed that Artesunate/Amodiaquine caused cognitive impairment in healthy mice at clinical dosage [15].In this study, the Light/Dark box was used to evaluate anxiety and fear. The parameters considered were time duration spent in the light chamber, number of transitions, rearing and line crossing. Rodents possess inherent contrasting tendency to abhor brightly lit environment and at the same time love to explore novel and new environment [9]. When the animal is anxious, it will explore less of the new environment and when it is less anxious, there will be more exploration. Thus, there will be increased in the above parameters in reduced anxiety and vice versa [10]. Time spent in the light chamber was significantly reduced in the Dihydroartemisinin/Piperaquine and Arthemeter/ Lumefantrine groups. The animals in these two groups preferred to stay in the dark chamber more and it’s indicative of increase anxiety in these groups. This finding thus suggests that Dihydroartemisinin/Piperaquine group and Arthemeter/Lumefantrine cause increase anxiety. Though the time in the light chamber was not significantly reduced in the untreated group, reduction in indices like transition, line crossing and rearing strongly suggest increase anxiety in this group. Our finding thus indicates that malaria infection cause increase anxiety. The Artesunate/Amodiaquine group was the only experimental group that anxiety was not increased. It is not very clear why this is so. However, an earlier study showed that Artesunate/Amodiaquine caused anxiety and fear in rodents (15]. At this stage it difficult to know whether the increased anxiety in Dihydroartemisinin/Piperaquine and Arthemeter/Lumefantrine groups is due to the malaria infection, the drugs or both. More studies are still needed to unravel this.Anxiety is mediated by the GABAergic mechanisms. Agents which reduce anxiety stimulate the GABA receptors while those that inhibit transmission through this receptor causes anxiety [16]. It is possible that increased anxiety noticed in this study may be mediated through similar mechanism.

5. Conclusions

- Malaria infection lasting between 3 to 5 days does not affect cognition. However, there was increased anxiety in untreated malaria infection. Furthermore, anxiety was increased in infected mice treated with Artemether/ Lumefantrine and Dihydroartemesinin/Piperaquine.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML