-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2017; 7(1): 32-40

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170701.06

Physical Punishment of Children: Dimensions and Predictors in Egypt

Huda Assem Mohammed Khalifa

Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Huda Assem Mohammed Khalifa, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

PURPOSE: The purpose of this research is to investigate the impact of socio-demographic predictors (age, gender, monthly income, number of children in family, marital status, and level of education) on physical punishment through three dimensions: ‘Child will get spoiled if we don’t hit him with a stick’, ‘It is necessary to beat the child strongly to discipline him’, and ‘In adolescence it is necessary to beat child and reprimand him verbally’. METHOD: The research undertakes a survey based on a sample of 1523 children 10–16 years of age across of Assiut governorate during the period May 2015 to December 2016.RESULTS: Findings show that the dimensions ‘In adolescence it is necessary to beat child and reprimand him verbally’ and ‘It is necessary to beat the child strongly to discipline him’ have a significant influence on physical punishment, and that the predictor, number of children in family, affects the incidence of physical punishment through each of the three dimensions. CONCLUSION: Based on the dimensions the research shows that children in Egyptian families face physical punishment especially when there are fewer children in the family, i.e. when parents have a smaller number of children they are more likely to use physical punishment for disciplining.

Keywords: Physical punishment, Disciplining, Egypt, Children, Predictors

Cite this paper: Huda Assem Mohammed Khalifa, Physical Punishment of Children: Dimensions and Predictors in Egypt, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 32-40. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170701.06.

1. Introduction

- Physical punishment could be used by parents from all social, economic and educational backgrounds, to harshly discipline their children because of increased stress levels leading to low parental tolerance. Moreover, because parents today spend relatively little time with their children due to lack of time, it is highly possible that they wrongly perceive their children’s behavioural patterns. Negligence and lack of display of affection from parents cause children to display symptoms of aggression and other externalizing behaviours. It is assumed, too, that children sometimes resort to negative behaviours in order to get their parent’s attention, which in turn causes the parents to lose their temper and use physical punishment as it is an easy disciplinary method. Although physical punishment does not carry any added advantage (no research to date has confirmed a positive effect on children), it is also true that moderate use of physical punishment does not always have negative outcomes. The purpose of this paper is to show that physical punishment is a construct related to parental beliefs about disciplining such as: ‘Child will get spoiled if we don’t hit him with a stick’, ‘It is necessary to beat the child strongly to discipline him’, and ‘In adolescence it is necessary to beat child and reprimand him verbally’. The research also shows how socio-demographic variables like age, gender, number of children in family, marital status, educational level, monthly income, and residence affect the incidence of physical punishment.

2. Literature Review

- The effects of physical discipline on children have been studied by Choe, Olson and Sameroff (2013) in relation to inductive discipline. Based on a study conducted on 241 school age children, the authors observed that there is a two-way relationship between both kinds of discipline and externalizing behaviour of children. Inductive discipline can cause less externalizing behaviour among children than physical discipline, but at the same time children with externalizing problems can elicit physical discipline from parents. Chronic use of physical punishment can also affect the child’s brain development leading to low cognitive skills according to Tang and Davis-Kean (2015). The use of physical punishment on children with low academic skills results in poor achievement in reading and maths whereas cognitive stimulation at home can help children to develop better academic performance, so it was concluded that the type of parental response to children’s academic performance is an indicator of their academic skills in later years. The impact of physical punishment on cognitive skills has however been disproved by Paolucci and Violato (2004). According to another article by Smith, Springer and Barrett (2011), harsh physical discipline can negatively affect the socio-emotional status of children although this has also been disproved by Paolucci and Violato (2004). Smith et al. (2011) made a sample study of 563 Jamaican adolescents to prove that physical punishment can result in negative emotional and behavioural patterns in children, and that these children are less inclined to developmentally adjust than their non-victim counterparts. This study also disproves the Jamaican belief that “saving the rod spoils the child”. Physical punishment has also been proven to be a contributing factor for antisocial behaviour by children (Grogan-Kaylor, 2004), but the article dismissed the assumption that frequent use of physical punishment can increase the degree of children’s antisocial behaviour because no relationship was established between them. The result is consistent with Lansford et al’s (2011) findings which state that although physical punishment can influence externalizing behaviour in children, the degree of influence is however not associated with other factors like the age of the child. They also argued that the level of physical discipline (harsh or mild) does not have a differentiated influence on children’s antisocial behaviour. In another study by Simons, Johnson and Conger (1994) it was concluded that physical punishment as such has no impact on children’s aggressive behaviour, but they argued that when accompanied by parental neglect physical punishment does indeed become a contributing factor toward aggression in children. There is another aspect of the impact of physical punishment and that is the presence of variable factors like parental marital status, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity. Lansford et al. (2004) observed that the negative impact of physical punishment on children’s externalizing behaviour is greater for European American adolescents than for African American adolescents, however they found no relation of physical punishment to the children’s gender.Saunders and Goddard (2008) studied 8 years old Australian children to learn about their experience with respect to physical punishment. The children commented that parents often hit them under-cover to avoid being seen by others indicating that the children realized parents are aware that hitting them can get them into trouble. The children also thought that parents hit children because the children are not of age to have any say. When publicly hit, children often feel embarrassed which can lead to low self-esteem. Often the cause of the problem lies with the parents, as Dobbs, Smith and Taylor (2006) found when they studied 80 children between 5 and 11 and observed that children often do not understand the language in which parents dictate the rules. Moreover, if children perceive they are being treated differently to their siblings, they are prey to feelings of powerlessness. The authors suggest the use of inductive discipline (explaining or reasoning) as most children feel that physical punishment hurts them not only physically but also emotionally.The effect of physical punishment on children has proven to be different based on the child’s gender. Parent et al (2011) studied the differential impact of harsh and permissive treatment on boys and girls with both genders showing a high risk of disruptive behaviour if they are the victims of such treatment, while permissive treatment alone causes only boys to display the risk of disruptive behaviour. In this context, children of both genders perceive that boys are more likely to receive physical punishment than girls. However, another study (Sorbring et al, 2008 also revealed that children do not complain about differential treatment if they have siblings of opposite gender. Differential treatment based on gender has been supported by Sorbring and Palmerus (2003) too. Leve and Fagot (1997) argued that the behaviour of children is the cause of physical punishment. Single parent family children have more disciplined behaviour than children from two-parent families. Physical punishment is inflicted less by single parent families who prefer problem-solving strategies to the latter. However, in both cases there is no differentiation based on the gender of either parents or children. Based on another study on Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong, Shek (2008) hypothesized that parental control is higher for boys than girls because of a higher level of expectations for boys, and also that fathers exert more control over boys than girls and mothers exert more over girls than boys. Both hypotheses were positively proven despite the perception that parents expect more from girls than boys. This study has also been substantiated by McKee et al (2007). The psychological status of parents is another key factor in physical punishment. Simons et al (2013) disproved the general assumption that warm and nurturing parents usually do not use physical punishment since they observed frequent use of physical punishment by these parents. However, their study also showed that parents who are highly responsive use less physical punishments than their counterparts with low responsiveness. According to Pereira et al (2015) parental stress and family conflicts were directly related to physical punishment of children. However, the economic status of a family acted as a moderating factor for parental stress and family conflicts, since children from low economic status families experienced more harsh treatment than their counterparts from high economic status families. This result substantiates the findings of Pinderhughes et al (2000) who further added that low economic-status related stress resulted in parental negative perceptions of their children’s attitude which thus lead to high levels of physical punishment. This was also supported by Moraes et al (2005) who studied poverty as a factor that was directly related to the physical punishment of children. Parental stress has also been highlighted by McLoyd (1990) who associated such stress with ethnicity. The author observed that due to high society induced stress, African American parents implemented harsh treatment on their children. Contrary to economic status being contributing factor to physical punishment, Horn, Cheng and Joseph (2004) found no significant relation between low, middle or high economic status and preferred parenting styles. The authors also found that while low socioeconomic status parents would consider spanking as a correctional method for children between one and three years, middle and high socioeconomic status parents were inclined to reward their children for positive behaviour. Lansford et al (2012) studied disciplinary measures like reasoning, yelling, denying privileges and spanking on the basis of ethnicity. Their study concluded that while the first three methods were used more by European American than African American mothers, spanking is used in equal measures by both groups. However, teachers complained more about the externalizing behaviour of European American children which lead to harsh treatment. This finding has also been supported by Polaha et al (2004) who further concluded that ethnicity plays no role in mothers’ perceptions of children’s behavioural problems, which then lead to physical punishment. Parental depression has been studied by Callender et al (2012) and they concluded that depression caused parents to be hostile toward their children. The reason, the authors argued, was that child affection lead to a positive parent-child relationship; however depressed parents sometimes failed to perceive positive behavioural patterns in their children which thus lead to a low tolerance level.Khoury-Kassabri (2010) studied 102 Jewish mothers and 132 Arab mothers of 6 to 9 year old children and concluded that a significant 15 percent of mothers support physical punishment like slapping or spanking while 10 percent of mothers prefer using objects like a belt or hairbrush. One noteworthy finding of this study is that these results tally with the findings for Swedish mothers although physical punishment is banned by law in Sweden. The results are also much lower than for USA mothers 80 percent of whom support physical punishment. While the Israeli Supreme Court has found physical punishment illegal, although not banned, it is legal in the USA. Juby (2009) has studied the effects of environmental factors like education, marital status and level of income on parental attitude towards children and observed that low educational status of parents elicits harsh parenting including physical punishment, a finding also supported by Khoury-Kassabri, 2010. Juby also found that income level is indirectly related to corporal punishment, but marital status does not play any significant role although single parents are more prone to physically punish their children.Recent researchers are also focusing on the parenting patterns of fathers and mothers. Belsky and Fearon (2004) found no significant difference in maternal and paternal child rearing patterns, but assumed that parents learn from the childrearing styles of other parents especially if they have positive outcomes. This result has also been substantiated by Jansen et al. (2012) even after considering other factors like parental psychological or behavioural problems and family dysfunction. However, one variable, socioeconomic status, has been associated with maternal harsh parenting but not paternal harsh parenting. In this context, Day, Peterson and McCracken (1998) affirmed a difference in physical punishments like spanking used by mothers and fathers with mothers more inclined to use spanking than fathers. In addition, the authors concluded that boys and children older than 7 years of age experience more physical punishment like spanking than girls and children less than 7 years old. With regard to ethnicity, this study proved that black mothers use spanking as physical punishment more than black fathers. Physical punishment may be a common parental practice, however parental support can have moderating effect on child aggression and depression. Harper et al (2006) observed that children who were victims of maternal harsh parenting who have supportive fathers showed low levels of aggression but high levels of depression, which means when mothers use physical punishment the fathers’ support can have a moderating effect on the children’s aggression but not depression. On the other hand, the authors observed that children who are victims of paternal harsh parenting but have supportive mothers showed low levels of depression but high levels of aggression which means when fathers use physical punishment the mothers’ support can have a moderating effect on the children’s depression but not aggression.

3. Methodology

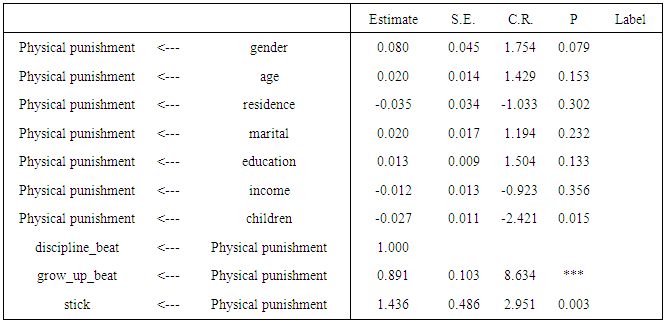

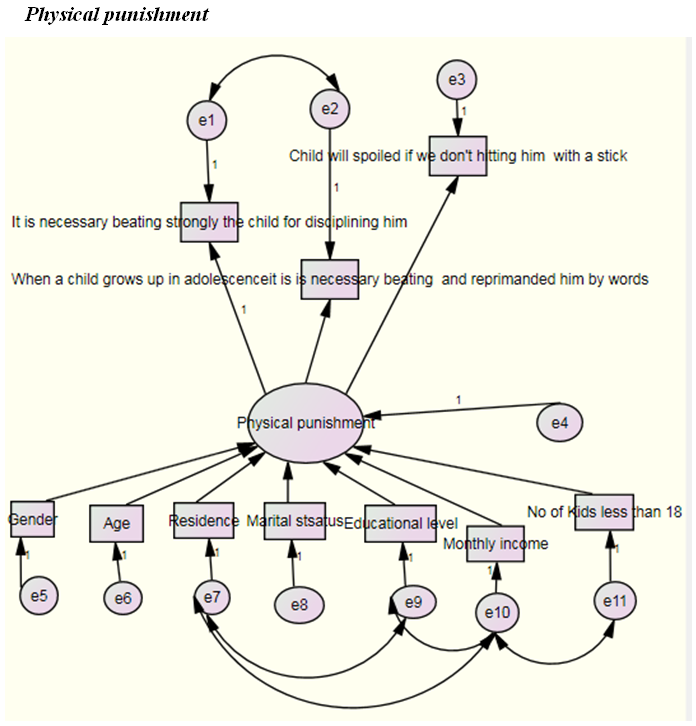

- The research considers a positivist approach since the analysis is quantitative in nature. It considers a sample of 1751 children 10–16 years of age across Assiut. A 23-item questionnaire was distributed to all the children (male and female) by randomly selecting the sample and was answered during face-to-face interactions. Both open-ended and close-ended questions were used. The quantitative method includes Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Most of the items are structured as per the Likert scale of 1 to 5. Amos software is used for the statistical analysis (i.e. EFA). CFA with path diagram models is used, and thus the goodness of fit test is estimated for the SEM. Instrument: Reliability, Validity and Factor ExtractionThe reliability of the questionnaire is measured by KMO, Bartlett’s test. Disciplining with prevention as a construct of the following observed dimensions was tested: ‘Child will get spoiled if we don’t hit him with a stick’ (‘beating with stick necessary’ or ‘stick’), ‘It is necessary to beat the child strongly to discipline him’ (‘beating to discipline’, or ‘discipline_beat’), ‘In adolescence it is necessary to beat child and reprimand him verbally’ (‘beating is necessary to make children grow up’, or ‘grow_up_beat’(. First, the suitability of a factor analysis was tested via KMO, Bartlett’s test. The closer the values of KMO test to 1, the better. The result obtained, 0.518, shows moderate suitability. The sphericity assumption holds since Bartlett’s test is significant at the 5% level. Therefore, the factor analysis can continue. From the communalities table it is evident that ‘child reward’ and ‘explain many times’ have low shared variance. The remaining variables have moderate levels of shared variance. Looking further at the extracted factors table, the above three extracted factors are associated with the variables included in the dimension. The criterion for extraction is an Eigenvalue higher than 1. Predictive factorsTesting for a predictor or an independent variable which can statistically and significantly influence the dependent variable ‘physical punishment’ is important to begin with. This involved two steps. Firstly, the dependent variable was extracted and evaluated according to its three determinant variables using EFA. The three variables which construct physical punishment have been identified – ‘beating with stick necessary’, ‘beating to discipline’, ‘beating is necessary to make children grow up’. These were grouped into two factors. Secondly, a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis was carried out for the dependent variable (physical punishment) to illustrate its association with the various independent socio demographic variables (age, gender, residence, parental marital status, parental educational level, monthly income of family, and number of children less than 18 years).Limitation and future scope of researchThe main limitation is the time frame of the children’s ages which might not be applicable 5 years hence. Secondly, the results for Assiut might not be generalizable for other countries. The paper could initiate future research in the same line in other nations, especially western ones and then comparative analysis could be carried out between western and non-western nations on the same basis.

4. Findings

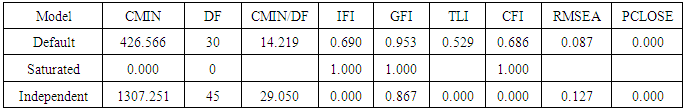

- The results obtained by CFA in Amos for the first two hypotheses are presented below in the path diagram, Figure 1, and Structural Equation Modeling analysis, Table 2.

| Figure 1. Path Diagram for the three dimensions and relationship with the socio demographic variables |

|

|

5. Conclusions

- These findings stress several aspects of parenting with its impact on the behavioural patterns of children, as well as the influence of children’s perception of the influence of parental stress and anxiety on their parenting. In sum, the findings from the chosen literature highlight that children’s aggression, shyness and feeling of confidence correspond to how the parents feel about their approach to and attitude toward their children. The cultural impact on parental styles has been explored and it is evident from the findings that cultural backgrounds definitely play a role in a child’s upbringing. The contradiction by Amato and Fowler (2002) stresses the fact that more cross-sectional studies are needed. One interesting finding is that parental styles can be hereditary as observed by Conger et al (2003) in that parents tend to use the same kind of treatment with their children that they received from their own parents. This brings to the fore the fact that any adverse impact of parenting on the parental generation is barely taken into consideration when it is the turn of that generation to become parents. The impact of parental training programs has been another element in this study and it has been comprehensively proven that such programs have a positive impact on parent-child relationship as well as on the behavioural patterns of children irrespective of gender. Moreover, although the parental attitude may vary according to the gender of the child, the impact is not gender related as has been proven by McKee et al (2007). One important fact that has been found by El-Sheikh and Elmore-Staton (2004) is that the impact of parental marital conflicts on children is diluted if the parent-child relationship is also in conflict. The number of studies regarding the topic of parenting styles and their impact of children’s emotional behaviour is huge, and this current paper has focused on only a few of them. Therefore, it is not possible to provide an exhaustive report on this issue as further studies are required. However, an important fact that can be concluded from the findings here is that while parental attitudes can positively or negatively affect a child’s behaviour, the reverse is also true, i.e. attitude of children can influence the impact of parenting (Chen et al, 2001). Finally, it can also be said that harsh parenting styles are more a social practice than an actual expression of parental beliefs. Although this paper proves that there is almost never any positive impact of harsh parenting, the practice is still prevalent in most societies in this world.That said, there remains a major concern in society today about the raising of children, and that is the child’s right to enjoy his childhood without being subjected to unnecessarily harsh punishments. The impact of harsh disciplinary measures is not the same for every child, and while some can go on to lead normal and happy adult lives, it has long term adverse physical and emotional impacts on most children. Child psychology is reversible, so proper care and therapy can help children be liberated from any of the constraints deriving from harsh parental upbringing that are felt during childhood. A child’s emotional and intellectual development is the reflection of what it experiences, both positive or negative, in the company of family, caregivers and community. Having a healthy and peaceful childhood creates emotional stability which is essential for the development of the brain. Constant exposure to difficult and tiring measures supposedly for instilling discipline among children makes them more reactive than adaptive. Long term experience of harsh upbringing can make children react by taking everything too seriously, which makes them less receptive to the many things that make childhood years enjoyable. Discipline is about teaching a child to participate effectively in the real world in a manner that has a positive effect on their own emotions and personality. Appropriate disciplinary measures can help children develop awareness so they can maintain self-discipline, but the effectiveness of disciplinary measures lies in how they are taught to children. A major principle for parenting relates to how they deal with their children’s unacceptable behavior. Rather than just forcing their children to abide by the measures, they also need to ensure that their children feel loved and supported by them.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML