-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2017; 7(1): 7-10

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170701.02

Attentional Biases for Emotional Faces in Trait Anxious Participants: The Effect of the Exposure Duration

Yi-Hsing Hsieh

Department of Guidance and Counseling, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, Taiwan

Correspondence to: Yi-Hsing Hsieh, Department of Guidance and Counseling, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, Taiwan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study investigated the effect of the exposure duration on the association between trait anxiety and attentional bias for emotional faces, such as angry, sad, and happy, using a dot probe task. A factorial experimental design was used with exposure duration and emotional valence as within-groups factors and trait anxiety as a between-groups factor. 72 college students recruited from two universities completed a trait anxiety inventory and then were directed to a dot probe task. In front of a computer screen, participants viewed an emotional face paired with a neutral face of the same individual for a short (300~500 ms) or long (800~1000 ms) duration, and responded to a blue dot that was on the location of an emotional face (emotional trials) or the opposite location (neutral trials). The attentional bias score for each emotion was calculated by subtracting participants’ median reaction times for emotional trials from neutral trials. The results indicated that when the exposure duration of pictures was short, high-trait anxious participants showed a significantly larger attentional bias score for angry face than low-trait anxious participants. However, there was no difference in the attentional bias for the angry face between high- and low-anxious participants when the exposure duration was long. In conclusion, the long exposure duration of emotional faces could cause a suppression of attentional biases for angry faces in high-trait anxious participants. The results were accounted for in terms of the interaction between bottom-up and top-down processes.

Keywords: Trait anxiety, Facial emotion, Attentional bias, Exposure duration

Cite this paper: Yi-Hsing Hsieh, Attentional Biases for Emotional Faces in Trait Anxious Participants: The Effect of the Exposure Duration, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 7-10. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170701.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Attentional bias refers to a preference for orienting attention towards negative information. A dot probe task [1] was often used to measure the attentional bias, in which the participants more quickly detected a dot appearing at the emotional stimulus than at the neutral one. Past research found the association between high-trait anxiety and attentional bias for the angry faces [2-4]. According to the schema theory [5], the attentional bias for negative information was through bottom-up processing, because the schema functioned as a filter through which anxious individuals selectively encoded and retrieved environmental information that was congruent with the schema. Therefore, people with trait anxiety were presumably possessed with negative schema and disposed to attend automatically to the negative information. However, much research found that emotions induced by the stimuli viewed during the study, such as angry faces, could also affect the attentional bias. For example, Mogg and Bradley [6] found that the participants with spider phobia showed attentional bias to the pictures when the exposure duration of the spider pictures was short as 200 ms, but they did not when the exposure duration was long as 2000 ms. Another study [7] found that the participants with high trait anxiety showed attentional bias when the threatening pictures were presented as short as 100 ms, however, the attentional bias was not shown when the presentation time of the threatening pictures was long as 1250 ms. Edwards [8] found that when the participants with high- trait anxiety were aware of the angry faces, the attentional bias was reduced. These results might be because the negative pictures triggered the amygdala and therefore induced the negative emotions [9], then a self-regulatory executive function (S-REF) [10] was triggered. A top-down goal directed attention away from the negative pictures. To sum up, the exposure duration of the negative pictures could affect the attentional bias for the emotional stimuli in the participants with high-trait anxiety.Past research stated above supported the hypothesis that participants with high-trait anxiety were hyperorienting to the threatening information at first and then disengage from it. However, eye movements might be a confounding of this explanation because when the presentation time for the threatening pictures was long, eye movements could also cause longer reaction times. Therefore, this study tried to use the vertical arrangement of the two emotional faces in order to reduce the confounding of eye movement because eyes moved vertically less often than horizontally [11].The purpose of this study was to explore how the exposure duration of emotional faces affected the attentional bias for emotional faces in the participants with trait anxiety. The hypothesis was that when the exposure duration was short, high-trait anxious participants would show the attentional bias for angry face, whereas this attentional bias could be suppressed when the exposure duration was long. To examine attentional biases for emotional faces, the dot probe task was adopted because it was capable of directly measuring how participants distributed their attention resources between the two different stimuli. One emotional (angry, sad, or happy) and one neutral faces of the same person were paired to serve as stimuli, and then participants responded to the occurrence of a blue dot that was either on the location of an emotional face or the opposite location.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Participants

- Seventy-two undergraduate students (13 males and 59 females) recruited from two universities’ subjects pool (a medical university and a normal university) participated in this study to fulfill the requirement of a general psychology course. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity.

2.2. Stimuli

- A total of 48 stimuli consisting of three types of face pairs, with 16 pairs for each, were used: angry–neutral, sad–neutral, and happy–neutral. They were photographed from 48 volunteers, each of whom displayed an emotional and a neutral face. Each facial emotion was rated by 60 persons. Faces were categorized as one type of emotion if more than 60% of raters agreed. In each pair, the emotional face was put either above or under of the neutral one with equal probability. Therefore, each participant must see 32 stimuli for each pair. Each picture was 7×5.5 cm as presented on a 17" color monitor. The distance between the closest sides of each picture was 0.6 cm. The whole experiment contained 192 trials divided into 2 blocks, one for long exposure duration and the other for short exposure duration.

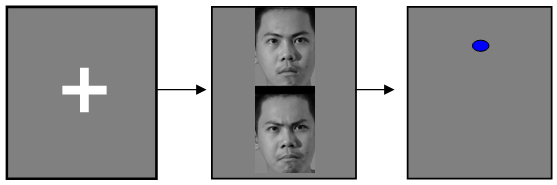

2.3. Apparatus and Procedure

- All participants completed a trait anxiety inventory (Chinese version) with good construct validity and reliability of Cronbach’s alpha .86 [12]. Then they were directed to the computer for a dot probe task. Stimuli were presented on a 17" color monitor. Participants sat in a chair in a dimly lit room. The monitor was placed at eye level on a table. The viewing distance, measured from the surface of the monitor to the participant’s eyes, was fixed at approximately 50 cm. The stimulus events started at a fixation display, then a face pair display, and finally a dot display (see Fig. 1). A fixation symbol “+” was first presented in the fixation display. The participants were instructed to fixate on the “+” throughout the trial. After 200 ms, the “+” disappeared and a pair of faces of the same person expressing different emotions were presented on the dark screen background for short duration (300, 400, or 500 ms at random) or for long duration (800, 900, 1000 ms at random). The reason why the duration was not fixed at one value was to prevent from expectancy. Finally, a blue dot replaced either one of the faces in the same location. The participants had to respond as soon as they detected the dot by pressing the “’” key if the dot appeared at the upper position or the “/” key if otherwise. In an emotional trial, a blue dot was on the location of an emotional face. In a neutral trial, a blue dot was on the location of a neutral face. The task lasted about 15 minutes.

| Figure 1. The stimulus events in a dot probe task: An emotional trial |

2.4. Attentional Bias Scores

- Attentional bias score was calculated as the following procedure. Firstly, the incorrect response (the error rate was about 2% for either long or short exposure duration) was excluded. Secondly, the median of reaction times for emotional and neutral trials in each participant were calculated respectively. Finally, the attentional bias score for each type of emotion was calculated by subtracting the median reaction time for emotional trials from the median reaction time for neutral trials. A positive score represented an attentional bias, whereas a negative score represented the opposite attentional bias.

3. Results

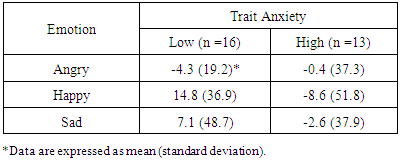

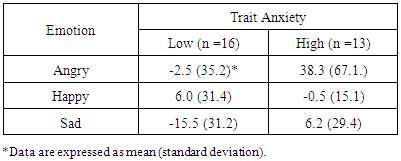

- The mean and standard deviation of trait anxiety scores were 54.7 and 11.4, not different from the norm. Sixteen participants who scored lower then the 25th percentile were chosen into the high-trait anxious group. Thirteen participants who scored higher than the 75th percentile were chosen into the low-trait anxious group. The following data analysis only included these two groups. The mean and standard deviation of attentional bias scores were shown in Tables 1 and 2.

|

|

4. Discussion and Conclusions

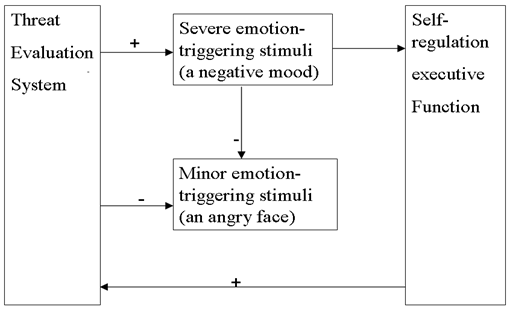

- This study aimed to examine the effect of the exposure duration of emotional faces on the attentional bias for emotional faces in the participants with trait anxiety. A major finding was that the association between trait anxiety and attentional bias for angry face was significantly positive when the exposure duration of emotional faces was short, whereas this association was reduced to become nonsignificant when the exposure duration was long. This finding corresponded to what was found in previous research [13, 14]. A possible explanation was that the emotional faces could activate the amygdala which then elicited an emotional state. Therefore, according to Mathew and Mackintosh’s model [15], a treat evaluation system (TES) was automatically executed when confronted with two competing emotion-triggering stimuli, namely an angry face and a negative emotion. Based on the operation of TES, attentional priority was given to the most emotionally influential stimuli, such as a severe negative mood, so that a minor emotional stimulus, such as an angry face, was inhibited (see Fig. 2). In addition to this unconscious bottom-up process, there was a conscious top-down process in which a negative emotional state triggered the S-REF [10] for producing a top-down goal of coping with the negative mood. The coping strategy affected the allocation of attentional resources in a way that inhibited the processing of negative information, such as emotional faces. This postulated inhibitory processing was supported by Cooper and Langton’s findings [16]. In conclusion, the long exposure duration of emotional faces could cause a suppression of attentional biases for angry faces in high-trait anxious participants. Although the findings of this study may be generalized only in undergraduate students, they are useful to be applied in counseling with students using suppression strategy for coping with negative life events. Since the suppression strategy is not adaptive [17], the school counselors may encourage the high-trait anxious students to shift their attention to positive stimuli when confronted with stress.

| Figure 2. A proposed model of the interaction between threat evaluation system and self-regulation executive function. A plus symbol represents enhancement, and a minus symbol represents inhibition |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I am grateful to the volunteers who allowed us to take their photographs for this study. I also thank Shu-Chen Lin for her assistance in collecting data. I gratefully acknowledge valuable comments from anonymous reviewers.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML