-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2017; 7(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170701.01

Mental Health Rehabilitation Based on Positive Thinking Skills Training

Mahbobeh Chinaveh1, Seyedeh Fatemeh Tabatabaee2

1Department of Psychology, Arsanjan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran

2Department of Law and Theology of Shahidbahonar University of Kerman, Iran

Correspondence to: Mahbobeh Chinaveh, Department of Psychology, Arsanjan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Mental health and mental illness are often given a low priority, despite growing evidence of the burden of disease and costs to the economy. Improving mental health and reducing mental illness will improve quality of life, public health and productivity. The aim of this study was to explore the effectiveness of positive thinking training (PTT) on mental ill-health among college students. For the present investigation, a battery of self-report questionnaires including positive thinking and General health questionnaires conducted on 103 college students. These students were randomly assigned to either an experimental group, or control group. Then experimental group was trained 12 sessions for positive thinking; while, control group was not trained for these training. Finally, after holding training sessions for experimental group, both groups were under pretest as a posttest. The results showed that there were significant differences between experimental and control groups on mental ill-health and positive thinking when the experimental group was under positive thinking training. Findings suggested that the education of positive thinking can decrease the mental ill-health and increase positive thinking. In primary health care there is some evidence that preventive interventions with groups at high risk of psychological diseases symptom can prevent episodes of ill-health.

Keywords: Positive thinking, Mental health, Training

Cite this paper: Mahbobeh Chinaveh, Seyedeh Fatemeh Tabatabaee, Mental Health Rehabilitation Based on Positive Thinking Skills Training, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20170701.01.

1. Introduction

- Along with enthusiasm for the new public health, over the past 20 years the interest in promoting mental health has grown [1-5]. The interest has grown recently for two main reasons: First, mental health is increasingly seen as fundamental to physical health and quality of life and thus needs to be addressed as an important component of improving overall health and well-being. In particular, there is growing evidence to suggest interplay between mental and physical health and well-being and outcomes such as educational achievement, productivity at work, development of positive personal relationships, reduction in crime rates and decreasing harms associated with use of alcohol and drugs. Second, there is wide acknowledgement of an increase in mental ill-health at a global level.The authoritative work undertaken by WHO and the World Bank indicates that by the year 2020 depression will constitute the second largest cause of disease burden worldwide [6, 7]. The global load of mental ill-health is well beyond the treatment capacities of developed and developing countries, and the social and economic costs associated with this growing burden will not be reduced by the treatment of mental disorders alone [8]. Evidence also has indicated that mental ill-health was more common among people with relative social disadvantage [9]. The global focus on mental ill-health has sparked interest in the possibilities for promoting mental health as well as preventing and treating illness. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined health as "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity" [10]. The concept of health enunciated by WHO as encompassing physical, mental and social well-being is more and more seen as a practical issue for policy and practice. In the other word, mental health is fundamental to good health and quality of life, it is a resource for every-day life and it contributes to the functioning of individuals, families, communities and society [11]. There is increasing recognition throughout the world need to address mental health as an integral part of improving overall health and well-being [12-14]. Improving mental health and reducing mental illness will improve quality of life, public health and productivity. The needs for mental health promotion are complementary to the needs for prevention and treatment of mental illness. In this regard, the past few decades have seen an increasing focus on psychological states associated whit general health and attempts to determine causes in increase health. In recent years, the importance of research on optimal psychological functioning and general health has gained growing recognition by scholars in diverse disciplines who have paid great attention to an understanding of the components and determinants of one’s thinking [15]. One cognitive factor that may help to reduce psychological disorder symptoms is internalized positive self-talk or positive thoughts (PT). For example, experimental studies have produced evidence that daily repetition of positive self-statements not only decreases depression but also increases self-esteem [16, 17]. The results of Ruthiga, Holfelda, Hansonb's study [18]indicated that exposure to the idea of PT (e.g. focusing on positive thoughts while suppressing negative thoughts and fears, self-healing, etc.) enhanced effort and responsibility attributions assigned to individuals for their cancer outcomes. Similarly, training in positive social cognitions has resulted in higher state self-esteem after having experienced rejecting and failure [19]. Positive thoughts are also positive predictors of self-esteem and negative predictors of negative affect among college students [20, 21]. A few study showed that people’s beliefs in their capacity to successfully manage relationships with others significantly influenced life satisfaction, self-esteem and optimism through positive thinking [22, 23]. In fact, the quality of our lives and that of how we live depends thoroughly on the power of our cognition. In the other words, excellence in thought increases the quality of life which is detrimental to our hopes and dreams [24]. Some studies have examined the ability of positive cognitive factors to predict declines in the psychological variables through which positive thinking may produce these declines [25]. Furthermore, positive thinking did improve the quality of life of patients with a life-threatening disease by inducing them to reduce their subjective probability of dying [26].Many believe that educational institutions should shoulder the responsibility for the development of pupils’ cognitive abilities and positive thinking. These are the abilities which strengthen the pupils’ perceptions of the world and consequently rectify the decisions they make [27]. Positive thinking is touted as very powerful both as a component of overall well-being and as a determining factor in therapeutic treatment outcomes. For example, in Generalized Anxiety Disorder images occurred while thinking about a negative future event [26]. Recently, authors have gained a great deal of attention thanks to positive thinking and a sort of psychological panacea, empirical research has found that there were many very real health benefits linked to positive thinking and optimistic attitudes. According to Jerry Shaw [28], positive thinking was linked to a wide range of health benefits including: longer life span, less stress, lower rates of depression, increased resistance to the common cold, better stress management and coping skills, lower risk of cardiovascular disease-related death, increased physical well-being, and better psychological health.Although Positive thinking is a widely-known term there is no consensus on a definition of the term. For the purpose of this study, positive thinking was operationally defined as a multifaceted entity of the cognitive state that incorporates choosing affirmative emotions and attitudes including joy, satisfaction, love, forgiveness, hope, courage, and gratitude.In this regard, this study examined the effect of positive thinking (PT) on how people view others’ struggles with mental ill health. The main objective was performed with the determining the effectiveness of teaching components of positive thinking on promoting mental health of college students. This objective was addressed using an experimental design that manipulated exposure to PT within the context of a positive thinking training in which a college student shares a personal mental-health experience. Within one PT exposure condition, the hypothetical student learns about ‘the power of PT’. Therefore, the hypothesizes of this study were: 1. There was positive significant difference between experimental group and control group in positive thinking after PT training.2. There was significant reduction in mental ill health in experimental group after PT training compared with control group.

2. Methods

- Participants and Research DesignThe method to perform the present study was a "semi-empirical" one in the form of a research project with pretest -posttest control group. In this method, we pre-tested the control and experimental groups. The experimental group was affected by the independent variable (positive thinking training), and the control group received no intervention. After the end of training sessions, both groups were post-tested. The statistical universe of the present research was all female student which 103 students (establishing cut scores on the pretest questionnaire, age range of 19-24, lack of chronic physical and psychological disorders, desire and ability to establish communication with others in the group, committing to attend the training sessions) were purposefully selected. Then, the mentioned 103 students were randomly assigned to two groups. One of the groups as "the experimental group" was taught positive thinking components and the other as "control group" was taught nothing.InstrumentTo asses mental health and positive thinking was used two questionnaires.The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ28)The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) was used to assess general health. The GHQ is one of the most used psychometric measures in health and psychiatry and has good reliability and validity [29]. It has four subscales: physical symptoms, anxiety, social dysfunction and depression. For grading score the tests, each right answer is scored as zero, one, two and three scores. A total score is obtained adding up all the scores. Each item is on a four point Likert-type scale, which assesses how a person has been feeling over the past few weeks. Higher scores indicated greater degrees of mental illness. Alpha coefficient for this study was .89. The Positive Thoughts QuestionnaireAccording to the Vincent Peale [30] definition of positive thinking, the researchers developed the positive thinking inventory that consisted of 20 items and used to measure positive thinking. Then, four professors in the fields of psychology and English-Persian translated were asked to judge the suitability and quality of the questionnaire. Consequently, five items were deleted and two items were modified. The positive thoughts questionnaire is a 15-item self-report measure that assesses the frequency of thoughts that "pop into" people's heads. In theory, these thoughts reflect activation of positive schemata and are associated with life event. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 to 5, on which 5 indicate greater frequency of thoughts; item scores are summed to produce a total score. Eventually, the validity and reliability of 15-item positive thinking inventory was examined. Split-half reliability, calculated on odd versus even items, was found to be .97, and coefficient alpha was .96.

3. Results

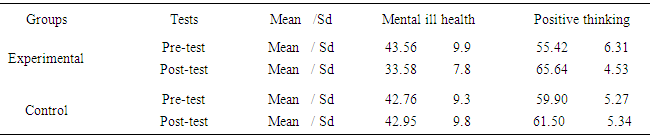

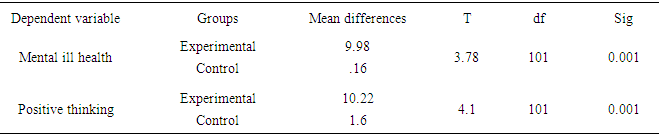

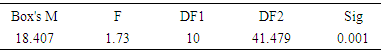

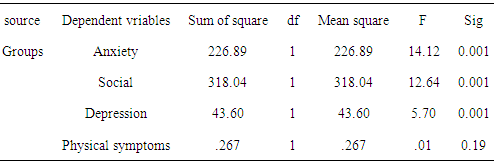

- As can be seen in Table 1, the mean of each dependent variable, i.e., mental ill health and positive thinking was different in the pre-test and post-test of the experimental group, while these means were slightly different in pre-test and post-test of the control group. Table 2 showed the mean of mental ill health has decreased and positive thinking scores has increased at the post-test of experimental group compared with its pre-test, while there was a slight difference between the means of post-test dependent variables compared with their pre-tests (It should be noted that lower GHQ score, is meant to increase the level of mental health).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Teaching and training of positive thinking components affected and improved positive thinking and decreases mental ill health of students (P<0.0001). These findings were in agreement with the results of the researches conducted by [20-22]. As Ruthiga et al [31] showed that positive thinking had an impact on improving the mental health of women with cancer. This study indicated that exposure to the idea of PT enhanced effort and responsibility attributions assigned to individuals for their cancer outcomes. Boyraz and Lightsey [20] proved that positive thinking components were significantly effective in enhancing individual's mental health, and reveals the point that positive thinking was associated with stress and multivariable of mental health that were indications of this important structure in the mental health of individuals. Moreover, Wilkinson and Kitzinger [32] pointed out that some people were more prone to psychoneurosis, while they avoided positive thinking as a coping style. When these people were given hope and were able to think in a more positive manner, they developed stronger immune systems. Consequence, a healthy immune system stands a better chance of fighting off diseases and allowing the person to regain good health. Part of the reason for this was that positive thinking and emotions give a person more energy and stamina; and that helps the immune system [33-35]. If individuals appraise dangers of environment more than their abilities, they will negative think and show symptoms such as high mental pressure, weak performance and anxiety [36]. The signs of good mental health are accurate observation situation and correct cognitive appraisal, self-ability to confront with problems and doing accurate responsibilities. As a result, individuals with high score in GHQ scale have worthy characteristics. It seems reasonable to consider, based on the results of this study, the fact that studying participants who trained, have developed mental health indirectly through the development of positive thinking as examined in this study (i.e. cognitive appraisal and problem solving). Thus, the results of the present study indicated that applying positive thinking training on students was highly effective in enhancing their compatibility. Researches are beginning to reveal that positive thinking are about much more than just being happy or displaying an upbeat attitude. Positive thoughts can actually create real value in our life and help us build skills that last much longer than a smile. When individual think in positive manner, it causes to produce positive emotion. The benefits of positive emotions don’t stop after a few minutes of good feelings subside. In fact, the biggest benefit that positive emotions provide an enhanced ability to build skills and develop resources for use later in life. Fredrickson refers to this as the “broaden and build” theory because positive emotions broaden their sense of possibilities and open their mind, which in turn allows them to build new skills and resources that can provide value in other areas of their life [34]. On the one hand, positive thinkers are more apt to use an optimistic explanatory style. People with an optimistic explanatory style tend to give themselves credit when good things happen, but typically blame outside forces for bad outcomes. They also tend to see negative events as temporary and atypical [35]. It is clear that optimism is a powerful tool in our repertoire to keep us healthy, happy, and alive.In this regard, recognizing positive thinking as a potential target for intervention raises to the issue an individual’s general tendencies which are by nature difficult to change. It is possible to modify such illness symptoms through increasing awareness of those that are maladaptive and training individuals in alternate patterns of thinking that are more effective. Hence, considering the results of this study and other consistent researches, we recommend the instructors, and trainers to hold positive thinking training courses by psychologists, which would definitely lead to mental health promotion of students to succeed at campus. College counseling professional may benefit from increased understanding of the relationship between perceived stress and positive thinking. Counselors may be able to support and guide students who are struggling to reduce stress by persuade them to increase positive thinking.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML