-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(5): 225-232

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160605.05

A Qualitative and Quantitative Examination of Using Positive Consequences in the Management of Student Behavior in Kenyan Schools

Pamela Awuor Onyango1, Pamela Raburu2, Peter J. O. Aloka3

1Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

2School of Education, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

3Psychology and Educational Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Peter J. O. Aloka, Psychology and Educational Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

he challenge of addressing students’ behaviour problems in Kenya cannot be over emphasized. The present study investigated the effectiveness of positive reinforcement in the management of student behavior problems in public secondary schools in Kenya. Thorndike’s Behavior Modification theory informed the study. Mixed methods paradigm that had both quantitative and qualitative approaches was adopted, together with concurrent triangulation design. The study population comprised 380 teachers from a total number of 40 schools that had 40 Heads of Guidance and Counseling (HOD), 40 Deputy Principals (DP) and 300 classroom teachers. A sample size of 28 Deputy Principals, 28 Heads of Guidance and Counseling and 196 teachers were involved. Reliability of the instruments was ascertained by conducting a pilot study in 9% of the population that didn’t participate in the actual study. Face validity of the instruments was ensured by seeking expert judgment by university lecturers. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and inferential statistics while the qualitative data was analyzed using thematic framework. The study findings revealed that positive reinforcement was effective in managing student behavior problems. The study findings may be a source of intervention to the school administration in the management of escalating student behavior problems. The study recommended training of teachers on better modes of students’ behavior management.

Keywords: Effectiveness, Exclusion, Student, Behavior Problems

Cite this paper: Pamela Awuor Onyango, Pamela Raburu, Peter J. O. Aloka, A Qualitative and Quantitative Examination of Using Positive Consequences in the Management of Student Behavior in Kenyan Schools, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 5, 2016, pp. 225-232. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160605.05.

1. Introduction

- Student behavior problems are regularly found in schools and teachers find it difficult to maintain order; the school authority too cannot guarantee safety to students (McCarthy, Johnson, Oswald & Lock, 1992). Many researchers and educationists have attempted to identify the most suitable methods of maintaining discipline among students (Busienei, 2012). Corporal punishment against children has been supported by legal and religious doctrines which include beliefs based on Judeo Christian and other religions (Watson, 1985). However, various children’s rights activists argue that corporal punishment is a violation of human rights standards (Archambault, 2009). Kopansky (2002) felt that corporal punishment is ineffective in managing student behavior problems and the formation of specific discipline plans may improve student behavior. Most countries in South Asia have legislation which protects children against physical assault. In Africa, the South African government has ensured the prohibition of corporal punishment within the educational system, and a number of teachers have been trained on alternatives to corporal punishment (Soneson, 2005). In Uganda, it was established that that corporal punishment was being unfairly administered and that lead to dissatisfaction and anger. These changes in policy have led to finding suitable ways of addressing behavior problems among students (Kiggundu, 2009). In addition, Damien (2012) in Uganda observed that stakeholders had ambivalent views on the use of corporal punishment in managing student behavior problems, not really behavioral theory used or sought after in our times. According to the theory, learning is determined by events that take place after a given behavior, and learning is gradual but not insightful. A response that is followed by a consequence that increases the probability of behavior (Alberto & Troutman, 2010). The use of positive reinforcement effectively increases positive behavior (Alberto & Troutman, 2010; Brown, 2013). A consequence that increases probability that a behavior occur again (Myers, 2013). Caldarella (2011) in the Western United States reported that treatment school showed statistically significant improvement in teacher ratings of school climate, while the control school either remained the same or worsened. Statistically significant decreases were also evident in students’ unexcused absences, tardiness, and office discipline referrals when compared to the control school. In another study, Bickford (2012) in America found that praise was found to be an effective in managing students’ disruptive behaviour. Study finding reported that teachers believed their students gained from behaviour specific praise, and they intended to continue using it. Teachers reported that they enjoyed working on their own use of praise and that they would continue to use behaviour specific praise. Strategies for increasing positive behavior in challenging behavior in secondary school students was investigated by Brown (2013) in New Zealand and the participants were students, teachers, educational psychologists and school administration. The study findings established that the use of positive reinforcement approaches increased positive behavior among the students. Positive and clear communication between the teachers and the students was vivid, suggesting that teachers relied on student behavior management policy. Agle (2014) revealed that an average student who showed problematic behaviour had received fewer praise notes from the teachers. Reupert and Woodcock (2011) conducted a study to identify Australian and Canadian pre-service teachers’ use, confidence and success in various behaviour management strategies and to identify significance differences between the two cohorts. Study findings indicated that pre-service teachers used low level corrective measures like verbal body language instead of strategies that prevent student misbehavior. In another study, Rahimi and Karkami (2015) showed that the teachers were not authoritative and praised students for good behavior. Further, effectiveness in teaching, motivation and achievement in learning English were found to be related to discipline strategies. Teachers who used involvement and recognition measures in managing behavior problems were effective. Further findings established that teachers who used punitive strategies were ineffective in teaching, since these lowered student motivation and caused learning problems. Guner (2012) in Turkey found that the use of rewards was effective in managing student behavior among children with special needs. Recognizing and rewarding desirable student behaviors was found to be effective in lowering undesirable behaviors. However, the teachers in the study used limited rewards such as Ching (2012) in the Philippines, found that when penalties were used for undesirable behavior even though school policy associated rewards and penalty system with positive discipline. The use of sanctions and rewards proved effective if based on school principals. Reward that was carefully offered encouraged students to compare their own performance with to their peers. Study revealed that the mostly used reward types were certificates, trophy, medals, additional points, credits and gifts. Dasaradhi, Ramakrishna and Rayappa (2016) established that classroom organization requires the teachers to create a motivational climate. This is done by motivating students to do their best and to gain excitement from what they are involved in. Two factors which are important in creating such a motivational climate are value and effort. Students get motivated when they see the worth of the work that they are doing and the work others do. Teachers should encourage effort through specific praise by telling the students specifically what they’re doing that is good and worthwhile. In a study by Ajibola and Hamadi (2014) disciplinary measures in Nigerian Senior Secondary Schools established that disciplinary measures undertaken was determined by causes and kinds of disciplinary problems. It was believed that rewards were useful in the management of student behavior problems. In addition, Bechuke and Debela (2012) in South African schools revealed that misconduct among learners resulted from the use of rewards and specific rules. That the urge to behave well comes from within an individual, is self-initiating and is not related to extrinsic reward or praise. It was argued that rewards destroy the inherent intrinsic motivation of the student by reducing the exchange of the reward to manipulative, demoralizing and dysfunctional exchange that reduces the interest of the student in learning good behaviors. Damien (2012) revealed that alternative corrective measures included exclusion, sending the culprit to the head teacher’s office, rewarding students’ good behavior, written public apology and giving more homework. These findings also indicated that principles of education require that rewards should not be used quite often and should also be applied conveniently. In another study, Semali and Vumilia (2016) in Tanzania revealed that teachers faced challenges in using rewards and sanctions in the management of student behavior problems. Ndembu (2013) in Kenya suggested were involvement of parents in student discipline, guidance and counseling, strengthening of prefects’ body, improving of relationship between teachers and students, rewarding positive behaviors and addressing the grievances of the students effectively. The government of Kenya banned the use of corporal as a result of the Children Act, 2001 (Government of Kenya, 2001). This was passed in order to protect children from violence and inhuman treatment (Government of Kenya, 2010). Teachers were required to practice measures opposed to corporal punishment that would curb behaviors.; some of the discipline strategies used in schools are manual punishment, guidance and counseling, exclusion and positive reinforcement (Agesa, 2015; Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2005; Ndembu, 2013). Since the ban, behavior student behavior problems still persist (Kindiki, 2015). Therefore, the present study determined the effectiveness of positive reinforcement in managing student behavior problems.

2. Methodology

- The current study employed concurrent triangulation model in which both quantitative and qualitative data was collected. Target population for the current study consisted of 300 teachers, 40 deputy principals and 40 heads of guidance and counseling in public secondary schools in Bondo Subcounty of Kenya. Stratified random sampling technique was used to identify the schools and participants. The Krejcie and Morgan (1970) sample size determination table was used in the study to determine a sample size of 28 deputy principals, 28 heads of guidance and counseling and 196 teachers. Questionnaires were used to collect data from teachers (McLeod, 2014). Deputy Principals and heads of Guidance and Counseling were participated in an in-depth interview. To ensure validity, the researcher developed the instruments with the help of expert judgment of two supervisors in the department of Psychology and Educational Foundations of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology. Show us you questionnaire Piloting of the research instruments was done in 9 % of the total population that were not part of the study population. Quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation. The questionnaires were sorted, coded and analyzed by means of Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 22. Qualitative data from interviews was analyzed using Thematic Analysis, which followed the principles of thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke (2006).

3. Results and Discussion

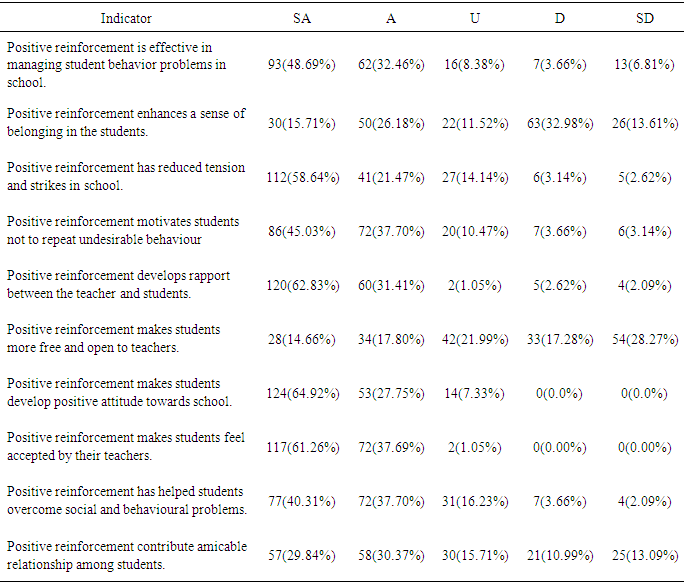

- To explore the effectiveness of positive reinforcement in the management of student behavior problems, the researcher employed a Likert scale with five options: strongly agree (SA), agree (A), undecided (U), disagree (D) and strongly disagree (SD) to establish the views of respondents. Table 1.1 was used to represent the descriptive statistics.

|

|

4. Conclusions

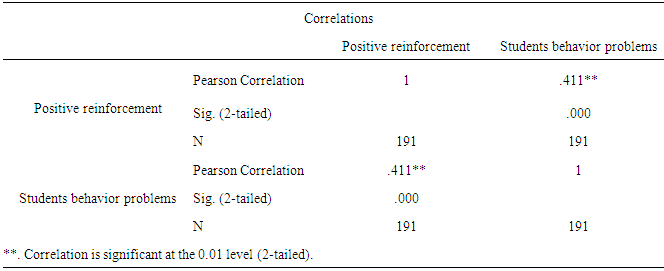

- The current study findings revealed that there was a positive association between positive reinforcement and management of student behavior problems. From the quantitative findings, it was revealed that positive reinforcement had reduced tension and strikes in school. Additional findings established that positive reinforcement created rapport between students and teachers and also helped students overcome social and behavioral problems. Qualitative findings indicated that positive reinforcement contributed to motivation of learners, modification of behavior and the imitation of peers. However, it was established that positive reinforcement may not work in all situation. There is therefore need for teachers to examine and evaluate the use of positive reinforcement since this may contribute positively to student behavior change.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML