-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(5): 199-205

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160605.01

A Psychometric Evaluation of Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS) of University Students

Ashraf Atta M. S. Salem1, Nasser S. Almenaye2, Cecilie Schou Andreassen3

1Department of Language & Linguistics, Faculty of Business Administration, Sadat Academy for Management Sciences, Egypt

2Department of Psychology, College of Social Sciences, Kuwait University, Kuwait

3Department of Psychosocial Science, University of Bergen, Norway

Correspondence to: Ashraf Atta M. S. Salem, Department of Language & Linguistics, Faculty of Business Administration, Sadat Academy for Management Sciences, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: The popularity of using Social Networking Sites and Facebook has grown all over the world in general and especially in Arab countries in the recent years. Despite numerous advantages of using Facebook in terms of optimizing communication and socializing among individuals, in certain cases it become problematic and engender negative consequences in daily life. Objective: As there is no single instrument tomeasure Facebook addiction in Arabic language, the goal of the current study is to validate an Arabic version of Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS). Methods: Arabic version of the BFAS was administered to a sample of 835 Facebook users (female =711, male =124; undergraduates =494, postgraduates=341) and analyses were performed. Results: As found previously for the original version, a one-factor model of the BFAS had good psychometric properties and fit the data well. Findings also revealed that the majority of sample are slight Facebook addictive (48.7%) and average Facebook addictive (46.7%). Very few students have severe Facebook addiction symptoms, it represents (1%) and normal Facebook addiction represents (5.5%). No differences were found between males and females in their Facebook addiction. Conclusions: The Arabic version of the BFAS seems to be a valid self-report to measure problematic use of social networking sites (especially Facebook).

Keywords: Psychometric properties, BFAS, Arab university Students

Cite this paper: Ashraf Atta M. S. Salem, Nasser S. Almenaye, Cecilie Schou Andreassen, A Psychometric Evaluation of Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS) of University Students, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 5, 2016, pp. 199-205. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160605.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Since it was launched in 2004 by one of Harvard University students, Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook has become familiar to most people. Today, several online social network sites (SNSs) exist, but Facebook seems by far to be the most popular with more than one billion active users worldwide (Kuo & Tang, 2014). Although SNS has been associated with many positive attributes such as entertainment and social interaction, red flags have been raised regarding the potential of users becoming addicted to it (Andreassen, 2015). Social networking addiction may be defined as “being overly concerned about SNSs, to be driven by a strong motivation to log on to or use SNSs, and to devote so much time and effort to SNSs that it impairs other social activities, studies/job, interpersonal relationships, and/or psychological health and well-being” (Andreassen & Pallesen, 2014, p. 4054). This definition captures some common addiction symptoms present in more traditional and formally recognized chemical and non-chemical addictions such as salience (i.e., preoccupation with social networking), tolerance (i.e., spending much more time social networking in order to feel satisfied), mood modification (using SNSs to feel better), conflict (social networking over most other important life aspects), withdrawal (experiencing withdrawal symptoms when prohibited from social networking), problems (social networking cause some kind of harm), and relapse (finding it difficult controlling or stopping the social networking behavior) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Andreassen, 2015; Brown, 1993; Griffiths, 2005; World Health Organization, 1992). In recent years, scholars have set out to measure excessive and addictive social networking, and several screening measures of SNS addiction have entered the literature. These measures have primarily focused on addiction to Facebook, while a few screen excessive use of other social networks, or addictive tendencies towards SNSs in general (Andreassen, 2015; Ryan et al., 2014). Among the former is the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS), a six-item questionnaire developed by Andreassen and colleagues (Andreassen, Torsheim, Brunborg, & Pallesen, 2012). Griffiths et al. recently argued that BFAS is probably the most accurate instrument for measuring Facebook addiction to date (Griffiths, Kuss, & Demetrovics, 2014), as it is builds on general addiction theory (Brown, 1993; Griffiths, 2005) and operationalizes Facebook addiction in line with the aforementioned addiction criteria (salience, mood modification, conflict, withdrawal, tolerance, and relapse) (Griffiths, 2005). Also, all BFAS questions are worded in accord with formal diagnostic addiction criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Further, the BFAS is brief, comes with recommended cut-scores, and has shown adequate psychometric properties across studies (Andreassen et al., 2012; Andreassen, Griffiths, Gjertsen, Krossbakken, Kvam, & Pallesen, 2013; Andreassen & Pallesen, 2014). It is worth noting that a modified and generic version of BFAS also exists (Bergen Social Networking Addiction Scale) (Andreassen, 2015). Currently, there is no formal diagnosis of social networking addiction in any psychiatric nosology (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; WHO, 1992). Still, this does not mean that addiction to SNS’s doesn't exist. It has been argued that SNS addiction is on the rise, along with the introduction of new mobile technology devises such as smartphones and laptops (Andreassen & Pallesen, 2014). However, as published studies usually involve small and often non-representative samples, solid prevalence statistics is currently difficult to come by (Andreassen & Pallesen, 2014; Griffiths et al., 2014; Ryan et al., 2014). Additionally, prevalence studies seem to employ various methodologies and cut-off procedures (Andreassen, 2015; Kuss, Griffiths, Karila, & Billieux, 2014). However, recent studies report prevalence of Facebook addiction between 1.6% (Albi, 2012) and 8.6% (Wolniczak, et al., 2013), whereas 12% has been reported to be problematic users of SNSs (Wu, Cheng, Ku, & Hung, 2013). The main aim of the study is to investigate whether six criteria of Facebook addiction (i.e., salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict and relapse) can be accounted for by one higher-order factor; Facebook addiction. These dimensions can be explained as follows:1. Salience: This dimension means that using Facebook becomes the most important activity in a person's life and dominates his or her thinking (preoccupation), feelings (cravings), and behavior (excessive use).2. Tolerance: It refers to the process whereby someone starts using Facebook more often, thereby gradually building up the amount of time spent in using Facebook.3. Mood modification: This dimension refers to the subjective experiences that people report as a result of engagement in using Facebook. This dimension has been labeled as "euphoria"(Griffiths, 1995, 1997). It may include tranquillizing and/or relaxing feelings related to escapism.4. Withdrawal: This dimension refers to unpleasant emotions and/or physical efforts that occur when using Facebook is suddenly reduced or discontinued. Withdrawal consists of moodiness and irritability, but may also include physiological symptoms, such as shaking.5. Relapse: It refers to the tendency to repeatedly revert to earlier patterns of Facebook addiction. Excessive use of Facebook is resorted after periods of abstinence or control.6. Conflict: This dimension refers to all interpersonal conflicts resulting from excessive Facebook use. Conflicts exist between the Facebook user and people around him/her. These conflicts may include arguments, neglect, lies and even deception. Some previous studies also conclude that SNS addiction is more prevalent among females (Andreassen et al., 2012) and younger (Andreassen et al., 2013; Andreassen et al., 2012; Turel & Serenko, 2012), whereas other studies have found higher prevalence among older users (Floros & Siomos, 2013) and in males (Cam & Isbulan, 2012). SNS addiction has in some studies been found to be unrelated to such demographics (Koc & Gulyagci, 2012; Wu et al., 2013). A recent study of predictors of personal use of social networks during working hours in a large employee sample (N=10,018) found that such “cyberloafing” is related to being male, younger, single, and higher educated (Andreassen, Torsheim, & Pallesen, 2014). That study did not assess SNS addiction, however. No studies, as far as we are aware, have measured social networking addiction in an Arabic sample thus far. Hence, building on previous conceptualizations and measures of Andreassen et al. (2012), the main objective of the present study was to test BFAS in an Arabic University student sample and examine the psychometric properties and factor structure of the scale. Against this backdrop the following hypotheses were tested: (1) the Arab version of BFAS will attain good internal consistency (alpha >.70) and an one-dimensional factor structure with high factor loadings for all items; (2) scores on BFAS will be positively associated with time spent on Facebook; (3) female gender; (3) lower age; and (4) lower education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

- A paper-and-pencil survey was distributed during one of the lectures after receiving passive consent form participants. Consents require students to sign and return a form if they refuse to participate, therefore, Ethical standards (VANCOUVER) was followed throughout the study. In order to improve the privacy of the students' responses, respondents were assured that their answers would remain anonymous, analyzed only by the researchers, and not shown to other teachers or parents. The time students spent to complete the questions were about 20 minutes. If respondents did not have a Facebook account, they were exempt from completing the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS). Responses to the BFAS items were screened for missing data and distribution. Fifteen cases were excluded due to extreme abnormalities in their responses, which clearly suggested that the questionnaire had not been filled sincerely. Also, respondents with more than three missing values were eliminated from further analysis. In total, 835 respondents (response rate in here or under participants) were included in the scale analyses.

2.2. Participants

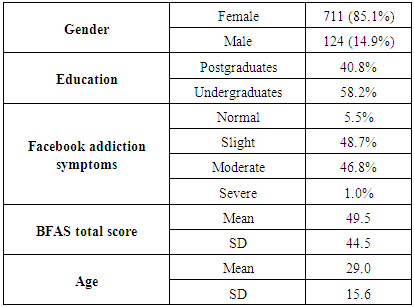

- A total of 835 participants took part in the study (84.1% females and 14.9% males). Participants were both graduates (59.2%) and post-graduate (40.8%) students at Hurgada College of Education, South Valley University, and Egypt representing twenty cities. The students participated voluntarily in the study after signing an informed consent. The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 40 years (M=29.0, SD=15.6). Table 1 presents the descriptive sample statistics.

2.3. Instruments

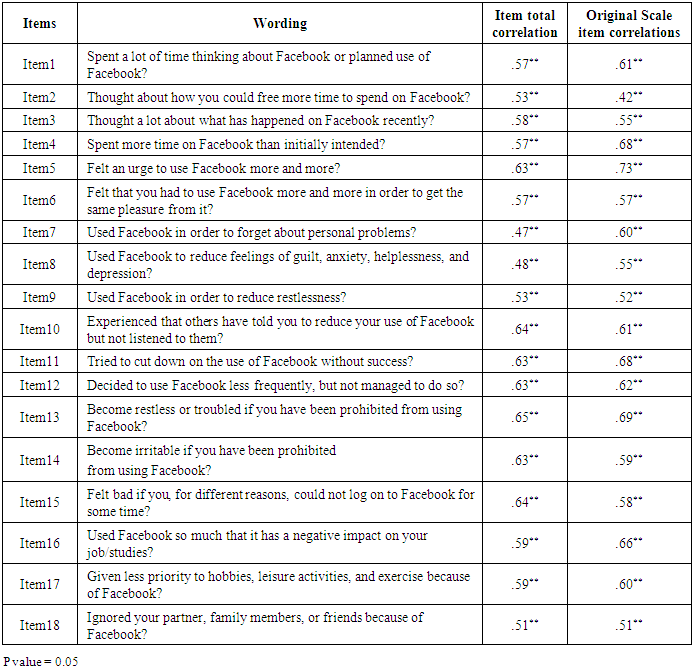

- Demographics. Questions regarding age, gender, educational level, and time spent on Facebook (minutes per day) were asked.Facebook Addiction: The Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (Andreassen et al., 2012) was developed to assess six core symptoms of addiction (Brown, 1993; Griffiths, 2005) as (1) salience, (2) mood modification, (3) tolerance, (4) withdrawal, (5) conflict, and (6) relapse. Initially, three potential items measuring each component were constructed – yielding a pool of 18 items worded in line with diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and the Game Addiction Scale (Lemmens, Valkenburg, & Peter, 2009). Then, the item with the highest corrected item-total correlation from within each of the six addiction components was retained in the final six-item scale. All items are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from (1) very rarely to (5) very often – asking how often during the last year the symptoms have occurred. The sum scores ranges from 6 to 30, where the suggested cut-score is set to >3 on at least four of the six criteria (polythetic scoring). In the present study, the Arab-language adaptation of the Bergen Facebook Addiction (BFAS) comprised the initial 18 items pool; to test whether these could be adequate for the Arabic sample. First, the translation was carried out by a professional translator from English language to Arabic language. Two professional bilingual translators then revised the scale. Discrepancies emerging between the English version and Arabic version of the scale were discussed and necessary adjustments were made to eradicate such discrepancies. The revised version of the scale was given to a sample of 50 persons in order to check the readability of the translation and whether students will understand it or not.

2.4. Analyses

- Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 18.0) for Windows software program was used to perform the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were computed for the demographic characteristics. Also, internal consistency was measured using Cronbach's Alpha coefficient in order to assess the extent to which BFAS items were interrelated. As the coefficient varies between 0 and 1, it may refer to a greater degree of homogeneity of the items of its value close to 1 (Khazaal et al., 2011, p. 2). Therefore, too high an alpha value may signal a high level of item redundancy meaning that a number of items asking the same question in slightly different ways. The acceptable alpha value should range from more than 0.70 and less than 0.90 (Steiner, 2008). In addition, the factorial structure of the BFAS was determined by an exploratory factor analysis on the correlation matrix (Velicer, 1976, p. 327 and O'Connor, 2000, p. 399). The extraction method used was principal components. A parallel analysis focusing on the number of components that account for more variance than the components derived from random data was also conducted. According to Byme (1989), this kind of analysis account for more variance than the components derived from random data remaining in a correlation matrix after extractions of an increasing number of components.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results and Sample Characteristics

- Table 1 shows the 835 participants of the original 850 participants initially screened, 15 participants were excluded because of the missing data leaving a final sample size of 835 participants. The average time daily spent online ranged from 30 to 360 minutes (M=195, SD=233.3).

|

3.2. Internal Consistency and Factor Structure

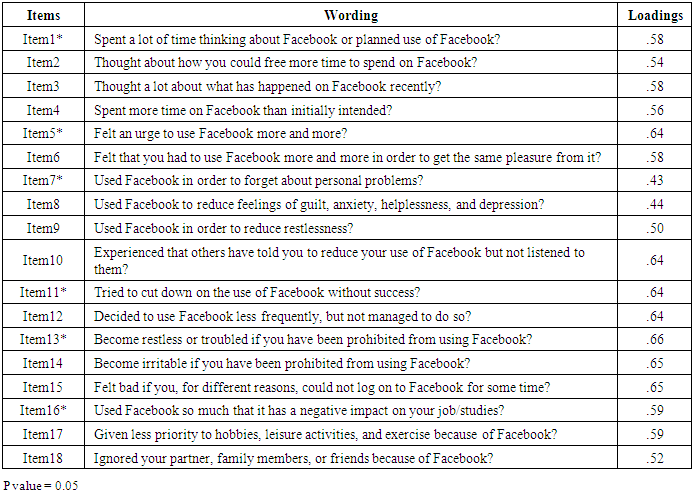

- The internal consistency, measured by Cronbach's coefficient, was too high (a=.88). It is worth noting that the Cronbach's coefficient of the original version of the scale was (a=.83). In addition, one-factor analyses as well as a parallel factor analysis were also calculated.Close inspection of table 3 reveals that all items in the scale resulted in acceptable goodness-of-fit measures except for item 7 (Used Facebook in order to forget about personal problems?) and item 8 (Used Facebook to reduce feelings of guilt, anxiety, helplessness, and depression?) that showed relatively low goodness-of-fit measures compared with other items.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

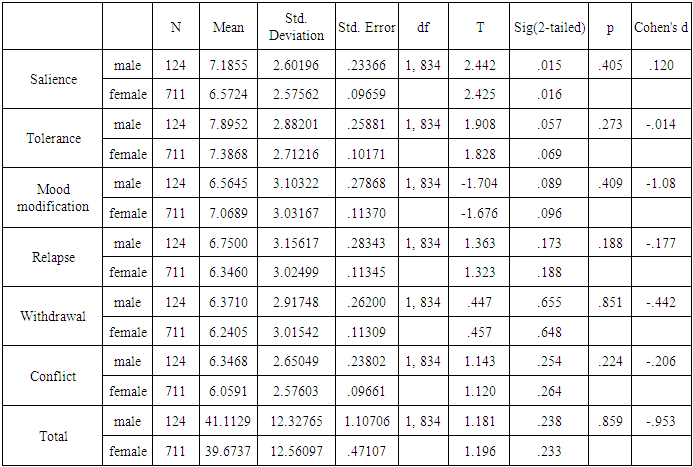

- The primary objective of this study was to validate and examine the psychometric properties of the Arab version of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale in a sample of Egyptian university students for twenty cities. Our first hypothesis was BFAS scale is reliable and valid to be implemented for Arab University students. The BFAS can be said to possess satisfactory levels of reliability and validity. It would appear that one of the differences with the sample group of the Norwegian university students (Bergen University) with regard to the original questionnaire is the organization of the items into the six main items investigated dimensions being evaluated. The interpersonal factor included variables related to: avoiding problems by engaging in using Facebook; anger or irritation when interrupted or disturbed while using Facebook; neglect of other activities in order to use Facebook; unease when not using Facebook; lower academic performance. These variables appear essentially to correlate with the criteria established by other authors (e.g. Andreassen et al., 2012). The six main dimension of BFAS investigated here are salience, tolerance, mood modification, withdrawal, relapse, and conflict. The main result of the study is that factor analysis indicates that a one-factor model of the BFAS has good psychometric properties and fits the Egyptian data well. The relatively small loadings found for only two items (out of 18 items). These two items related to the mood modification (Used Facebook in order to forget about personal problems?) and Used Facebook to reduce feelings of guilt, anxiety, helplessness, and depression?).With respect to the second objective- that of correlating different BFAS scores in the light of the gender variable, no differences were found between boys and girls regarding excessive Facebook use. This adhered the researchers (e.g. Rudolph, Klemz and Asquith, 2014; Sofiah et al., 2011) tendency to assess female university students' Facebook addictive practices. This result might be interpreted in the sense that both sexes now have the same possibilities of succumbing to the abusive or addictive use of Fcaebook (Casas, Ruiz-Olivares and Ottega-Ruiz, 2013).

5. Strengths and Limitations

- Limitation: The current study was limited to the psychometric properties of Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS) for the university students in the Arab regions. The relationship between BFAS components and personal traits is not included as one of the study focus as a separate study is designed for such purpose. In addition, it should be noted that female students exceeded their male counterparts due to the female students' desirability to participate in the study unlike male students. Strengths: The study is a pioneer study that tests the validity and reliability BFAS in Arabic sample, therefore, it develops an Arab version of BFAS to be used by other researchers in such countries. Future Research Directions: Further researches should be directed to the relationship between Arabic version of BFAS and the university students' personal traits, what Facebook addiction is related to (e.g. personality traits). Also, a regression analysis with BFAS as dependent variable, and age, gender, education and time spent on FB as independent variables should be focused on in further researches whether in Arabic environments or other places.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- All thanks go to all professors, lecturers, and assistant lecturers who have helped me to have this work to be real.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML