-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(4): 177-187

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160604.01

Construction and Validation of the Scale of Attitudes and Knowledge of Health Professionals toward to the Sexual Assault in Adult Women (AKSSAW)

Grace M. Ruiz1, Jose Rodriguez-Gomez2, Jose Martinez1

1Carlos Albizu University, San Juan Campus PR, Puerto Rico

2University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras Campus, PR, Puerto Rico

Correspondence to: Grace M. Ruiz, Carlos Albizu University, San Juan Campus PR, Puerto Rico.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The main purpose of this research is to create and validate a Scale of Attitudes and Knowledge of Health Professionals toward Sexual Assault in Adult Women (AKSSAW). According to Walker (1994), throughout history there is evidence that women, disregarding culture of origin and social status, have faced sexual assault. It is expected that health professionals act as agents of help to victims and offer support and understanding to them in such a sensitive moment. Unfortunately, in many cases, the health professionals working with people who have been sexually assaulted do not show sensibility or the adequate management required in these cases. By finding the more common stigmas and myths present among health professionals toward sexual assault victims, it is possible to determine the areas in need of strengthening and implement necessary workshops on the topic of sexual assault. With a Cronbach’s alpha of .90, standard errors of measurement for the scale of attitudes of 0.50 and for scale of knowledge .29, and discriminatory power of .79 for the scale of attitudes and .78 for the scale of knowledge the final AKSSAW version, which consists of 29 items (18 items that measure attitudes and 11 items that measure knowledge), is shown to be a reliable and valid instrument to measure the attitude and knowledge of health professionals toward sexual assault in adult women.

Keywords: Sexual Assault, Scale Development, Health Professional

Cite this paper: Grace M. Ruiz, Jose Rodriguez-Gomez, Jose Martinez, Construction and Validation of the Scale of Attitudes and Knowledge of Health Professionals toward to the Sexual Assault in Adult Women (AKSSAW), International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 177-187. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160604.01.

Article Outline

1. Literature Review

- Sexual assault is an act of violence that affects thousands of people worldwide, and the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico is no exception. Sexual assault can manifest itself through a variety of ways; for example, sexual abuse of minors, rape, lascivious acts, indecent exposure, and conjugal sexual assault, among others. Sexual assault has serious repercussions for the victim and the community. The present study emphasizes sexual assault in adult women as a manifestation of the sexual violence phenomenon. This phenomenon represents a facet of the worldwide domestic violence problem, which is considered the result of unbalanced power that one person has over another. Chasteen (2001) and Brownmiller (1975) concur that before the 1970s, there was little mention of sexual assault. Consequently, this led to the idea that sexual assault incidents were exceptional or unusual events (Walker, 1994). The feminist movement of the 70s transformed the definition of sexual assault and exposed sexual and physical abuse as the result of a struggle to control and exert power over women (López, 2009). Brownmiller (1975) indicated that sexual assault and the myths that surround this issue have served not only as a way of promoting a patriarchal culture, where men are assigned to positions of power, but also has kept women intimidated and subjugated to the will of men. Lonsway and Fitzgerald (1994) define the myths associated with sexual assault as attitudes and false beliefs regarding sexual assault with the purpose of denying and justifying the aggression of man to woman. In the 20th Century, Freud’s and other psychologists’ literature established the guidelines to be used in order to reconceptualize sexual conduct and categorize sexual deviations (Donat & D’Emilio, 1992). During this period many hypotheses and theories were developed, and these tried to explain the different means of sexual assault. The majority of these, however, described this behavior as a perverted one, and described the offender as a sick person (Donat & D’Emilio, 1992).In summary, sexual assault was redefined as a sickness, taking away responsibility from the victim and reconceptualizing sexual deviations from the perpetrator’s point of view. Sexual assault was considered a sexual act, more than an act of violence. The emphasis of the developed theories was to determine the sickness status of the male aggressor, not on helping the female victim in the recuperation process. In this way, the victimization of women was relegated to a by-product of men’s pathology (Donat & D’Emilio, 1992).Given this background, it is expected that health professionals act as agents of help to victims and offer support and understanding to them in such a sensitive moment. Unfortunately, in many cases, the health professionals working with people who have been sexually assaulted do not show sensibility or the adequate management required in these cases.Misconceptions could affect victim care. There could be myths that affect the management of victims. Myths regarding sexual assault include prejudice and stereotypes, or false beliefs about the act, the victims, or the perpetrators (Clarke & Lawson, 2009). An example of this is the belief that women who dress provocatively promote the assault. Similarly, there is a belief that when a woman says “no” to sex, she really means that she is interested in it. Myths like these are common throughout North America. Without a doubt, these myths affect the country of Puerto Rico. There are common phrases stating, “she got what she deserved,” or “if she would have really resisted then she wouldn’t have been abused.”Expressions like these tend to deny the gravity of sexual assault, therefore justifying the victimization of women. Clarke and Lawson (2009) explain that attractive women can be seen as provoking the assault, intentionally or not, to the point where perpetrators cannot control themselves. These authors have found that people who support these views are more inclined to attribute blame to the victim, based on the belief that the victim could have evaded the sexual assault by modifying her behavior somehow. People who adhere more strongly to these views are more likely to perceive victims as dishonest and less credible when compared to those that do not share these prejudicial beliefs.This negative effect can result in a diminished probability that help will be offered to the victim, given that research has demonstrated that people with strong acceptance of myths regarding sexual assault are less inclined to define the incident as such (Clarke & Lawson, 2009; Chasteen, 2001). At this instance, the health professional represents a crucial element for the victims of sexual assault. The professional should comprehend the internal dynamic of the affected person in order to offer attention with sensibility and warmth, achieving empathy when it is most needed. In some cases the sexual assault victim can experience revictimization when receiving treatment by a health professional, increasing levels of anxiety and discomfort with the help process. Clarke and Lawson (2009) found that, according to their predictions, the increase in blame attribution to the victim is associated with stronger feelings of anger and disgust, reducing feelings of sympathy. These negative affective reactions by the health professional are associated with a reduction in the will to offer help to victims. On the other hand, feelings of blame toward the aggressor are associated with stronger feelings of sympathy for the victim, increasing willingness to help victims. Nayak, Byrne, Martin, and Abraham (2003) indicated that socially enacted attitudes will have influence over health responses that are offered to victims, as well as over the reaction, interpretation and recuperation of victims given a traumatic event. It is for this reason that understanding the attitudes toward sexual assault is of vital importance in order to work effectively with this population.In a study performed by Campbell, Wasco, Ahrens, Sefl and Barnes (2001), the researchers found that 70% of their sample described their contact with a mental health professional as a healing experience. However, when these services are not appropriate, these contacts can be as threatening as the sexual assault itself, causing the victim to feel guilty about what happened and revictimizing her (Cambell et al., 2001; Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991). Factors that may affect the services offered by mental health professionals are the attitudes and knowledge they have regarding sexual assault. Conner (1994) argued that the beliefs and attitudes of a therapist have direct influence over the fundamental characteristics of therapy, such as genuineness, warmth, and empathy from the therapist to the patient. Draucker (1992) reported the need for therapists and counselors to critically examine their attitudes and beliefs, as this helps to avoid having a negative impact on the therapeutic process.Dye and Roth (1990) emphasized in their study that attitudes and knowledge of a group of psychologists towards victims of sexual assault. The authors found that the attitudes of therapists could directly influence the therapy, affecting both the quality of the therapeutic relationship and the therapist’s ability to project as empathic, reliable, and free of prejudice.These myths have been passed down from generation to generation, which makes it difficult to break cognitive schemes that have endured for such a long time. Therefore, the health professional should be a completely sensible person with the complete knowledge of the necessities of sexual assault victims. For this reason, it is important to understand how health professionals perceive sexual assault. They have the responsibility to safeguard and protect the rights of sexual assault victims. The sensibility and knowledge of the necessities required by sexual assault victims are precisely the variables that are investigated in this research. This is done by measuring the knowledge and attitudes that health professionals manifest regarding sexual assault, after constructing and validating an instrument for these purposes. This research has the potential of impacting in a meaningful way both the professional and the victim, given that at present there are no known published studies that evaluate this phenomenon in an interdisciplinary fashion. An interdisciplinary study brings a clear view regarding the attitudes and knowledge of health professionals, and in this way it is possible to detect the more common stigmas and myths toward sexual assault victims. By finding the more common stigmas and myths present among health professional, it is possible to determine the areas in need of strengthening and implement necessary workshops on the topic of sexual assault. The results of the present study intend to expose to the community the attitudes and knowledge that health professionals possess and also establish the base for an education grounded on reliable facts. However, the victims of sexual assault will receive the biggest impact from this study, given that it will promote the services that they truly need. This will help them feel more trust and safety in the therapeutic process, which in turn will help make a way to a better quality of life.This investigation intends to contribute to the wellbeing of this population, and to the field of Psychology, in general. Also, this research aims to provide more knowledge about sexual assault to different professions that are, in one way or another, involved in the offering of services to people who have experienced sexual assault.

2. Method

- Design of studyThe present study uses a nonexperimental, ex-post facto group comparison design, given that the purpose is to study the possible relationships between the variables at a given moment in time without manipulation from the researchers (Kline, 2005).ParticipantsThe sample that was studied was nonprobabilistic. The selection was carried out by the disposition of participants that comply with the inclusion criteria. The sample consisted of 135 participants, where 45 are psychologists, 45 social workers, and 45 nurses. The participants must: (a) possess a license to practice the corresponding profession, (b) be at least 21 years old, and (c) have Puerto Rican nationality. Participants were not excluded based on marital status, sexual orientation and/or having children.Sample selectionPsychologists were personally contacted through their identification at continued education activities or in the annual convention organized by the Puerto Rico Psychology Association. Social workers and nurses were personally contacted through participation in continued education activities hosted by the College of Professional Social Work in Puerto Rico and the College of Professional Nursing in Puerto Rico, respectively. Permission was obtained from both of the Colleges and the Psychology Association in order to invite prospective participants during continued education activities.Selection of experts for the study of content validityThe researcher personally approached nine experts with experience in sexual assault of women and test construction and asked for an appointment for them to participate in the panel of experts.Materials and InstrumentsThe materials and instruments for this study were the following: (a) informed consent form, (b) socio-demographic questionnaire, and (c) Attitudes and Knowledge Scale of Health Professionals regarding Sexual Aggression in Adult Women.Socio-demographic questionnaire. The socio-demographic questionnaire was used for the purpose of compiling information that would be used to obtain comparisons, conclusions, and generalizations. Some of the data compiled included information regarding age, gender, city of residence, employment status, education, profession, sexual orientation, religion and Puerto Rican nationality. Scale of Attitudes and Knowledge of Health Professionals toward Sexual Assault in Adult Women (AKSSAW). A preliminary version of AKSSAW (126 items) was developed and used for this study to evaluate the attitudes and knowledge of the participants regarding sexual assault in adult women. The instrument used to evaluate attitudes was answered using a four-point Likert scale composed of the following options: (4) completely agree, (3) agree, (2) disagree, (1) completely disagree. A higher score was given to those statements that represent a prejudiced attitude towards sexual assault; in this way a higher score represents a worse attitude. In addition, the instrument to assess the knowledge of participants was answered using a dichotomous format, where the participant indicated if they were true or false assertions.The items were developed using statements related to the attitude and knowledge towards sexual assault in adult women as a base. It should be noted that some items were obtained from the scale to measure attitude toward sexual abuse in a sample of clinical psychologists and pastors developed by Dr. María López Osorio, who granted permission to use some items from her scale in the creation of the AKSSAW. All items were reviewed by nine judges with experience in the areas of sexual assault and test construction. An informed consent for each judge was obtained. Once the judge consented to participation in the study, a form with instructions was provided, as well as the 126 items of the preliminary version, of which 76 explore attitudes and 50 relate to knowledge. The judges were asked to mark "essential" those items measuring attitude toward sexual assault, and "non-essential" those that do not measure the attitude toward sexual assault. The Lawshe (1975) method was used to select the items that would form part of the preliminary form of the instrument.First phase: General procedures The Lawshe (1975) method was used to establish the content validity of the AKSSAW. In order to achieve this, nine judges with expertise in the area of sexual assault and test construction were identified. The inclusion criteria used for selecting the judges indicated that they needed to be adults over the age of 21 and have a certification of assessment and treatment of victims of sexual assault from an accredited university or have at least two years of clinical experience with this population. Those professionals with two or more years of experience in the teaching of test construction and/or professional experience centered in this subject were considered experts in this area.First phase: Statistical analysis As set forth in the process, once the judges provided their evaluations of the scale and their socio-demographic data form, the researcher proceeded to apply the statistical formula to determine the content validity ratio (CVR) in order to decide whether the item should be part of the scale and performed a descriptive profile of the sample of judges. This is done by subtracting the total number of judges from the number of judges that marked the item as non-essential, and dividing this result by the total number of judges. The end result will determine if the item should be included. To do this, the researcher used the table developed by Schipper (1975), which takes into account the results obtained and the number of judges and indicates the minimum value of CVR that the item must have to be used.According to Lawshe (1975), when nine judges are participating, the minimum CVR should be 0.78; this will determine if the item should be included. Once the CVRs for all items are obtained, one can proceed to evaluate the content validity index (CVI). The latter is obtained by adding all the CVRs and dividing the result between the items that will be used. In order for a test to possess content validity, given that its purpose is for research use, it should have an index greater than .70. The purpose is to develop a scale that has acceptable CVI, which means that the instrument serves its purpose and measures what it intends to measure.Analysis of item discrimination Although it has been established that the included items are adequate and that the test has the validity required to be used appropriately, it is also necessary to determine whether the items possess an adequate discrimination index. Discrimination is the ability to separate the subjects who answered the items into two or more groups (DeVellis, 2003); in this case, participants will be divided into the group of people that possess favorable attitudes and the group of people who have negative attitudes toward sexual assault in adult women. This is required to use the Biserial discrimination index, which will help determine whether the items meet this purpose.Second phase: Statistical analysisAfter administering the instruments to the sample obtained during the second-phase, descriptive statistics (measures of central tendency and dispersion) and inferential analysis (correlations, measures of reliability and validity) were carried out.Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0.0 for Windows. After the information was collected, an identification code was assigned to each case record for quality control of the data entry process. In this way, it was ensured that a record was not lost or entered twice in the data set.Description of the sampleA frequency analysis was conducted to describe the sample in terms of socio-demographic information. Descriptive statistics, such as frequency distributions, measures of central tendency (mean and median) and measures of dispersion (standard deviation and variance) were completed. Chi-square tests were used to examine the characteristics of gender and level of education in terms of the relationship that these could have with the attitudes toward sexual assault in adult women.Reliability and validityReliability shows us the degree in which the scale produces consistent results, relatively free of measurement errors. In psychological tests, reliability refers to the degree that the test consistently measures individuals in a reliable manner. There are different types of reliability, but the most commonly used include test re-test reliability and internal consistency reliability. Internal consistency reliability was used for this study. Internal consistency reliability is based on the average of the inter-correlations between the test items. According to DeVellis (2003), internal consistency refers to the homogeneity of the items on a scale. If the items on a scale have a strong relationship with its latent variable, then these will have a strong relationship between them. As shown by DeVellis (2003), while we do not directly observe the relationship between the elements and the latent variable, we can certainly determine whether items are correlated with each other. Most of the correlations occur between items that share a common cause. The internal consistency coefficients increase according to the number of test items, and to the magnitude of correlation with each other. There are three methods for evaluating the internal consistency: Spearman Brown formula, the Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20) and Cronbach’s alpha formula. For the purposes of this study the Spearman Brown and Cronbach's alpha reliability analyses were performed.Acceptable ranges of reliability will depend on the extent and its purpose. According to Kline (2000), for evidence of clinical use it is recommended that the coefficient be .85 or higher, and for research it should be .70 or higher. Given that the Scale of Attitudes and Knowledge of Health Professionals toward Sexual Assault in Adult Women is used for research purposes, the researcher evaluated its reliability with .70 as a measure of good internal consistency. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was held to determine construct validity. According to Kline (2000), it is expected for items to have a factor loading of .30 or greater and factors to obtain an Eigen value greater than or equal to 1. The present study implemented the rotation of factors, where the purpose was to redistribute the variance to obtain a pattern of factors with greater meaning. The type of rotation that was used is Varimax, which focuses on simplifying the most factors matrix column vectors. The Varimax method maximizes the sum of variances of the required loads in the array of factors. Varimax rotation is what allows the researcher to obtain more extreme loads (close to - 1 or + 1) and others close to 0. The purpose of this rotation is to allow interpretation of the factors more easily and to indicate a clear positive or negative association between the variable and factor (or an absence of association) if the value is near 0. One of the necessary procedures performed during the validation of a scale is to determine whether the developed scale possesses discriminatory power, which is done with the Ferguson’s Delta formula. This discriminatory power is related to the test as a whole. In order to determine if the test possesses discriminatory power, a rate greater than .90 is recommended (DeVellis, 2003).

3. Results

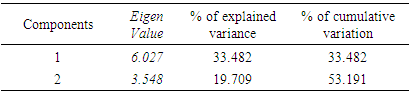

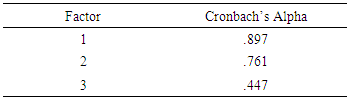

- Data were obtained through a socio-demographic questionnaire and the Scale of Attitudes and Knowledge of Health Professionals toward Sexual Assault in Adult Women (AKSSAW. The latter was validated in its content by nine expert judges in the area of sexual assault and test construction before giving it to the sample, according to the Lawshe (1978) method. Socio-demographic descriptionThe sample of this study consisted of 135 participants selected by convenience. Of these, 45 were clinical psychologists, 45 social workers, and 45 nurses. It should be noted that these professionals possess current licenses to practice their professions in Puerto Rico. In terms of the total sample, 85.5% (n = 115) were women and 14.8% (n = 20) were men. The average age of the sample was 43.51 (Std. Dev. = 13.45). Minimum reported age was 23 years and the maximum was 84 years.In terms of years in their profession the participants had an average of 13.87 years (Std. Dev = 11.53) of experience. In terms of the years of experience working with victims of sexual assault, the participants had an average of 2.01 (Std. Dev = 5.94) years of experience. The internal consistency seeks to determine if the answers of the participants are consistent throughout a test. De Vellis (2003) indicated that Cronbach’s alpha measure of internal consistency is an indicator of the proportion of the variance in scores on the scale attributed to true scores. To establish whether the scale of attitudes toward sexual assault in adult women counts with adequate psychometric properties, an analysis of internal reliability was performed. According to Kline (2000), the expected minimum ratio is of .70.The first part consists of the scale of attitudes and the second consists of the scale of knowledge. A Cronbach's alpha index of. 81 was obtained, which points out that the scale of attitudes has an adequate level of internal consistency (Kline, 2005). Similarly, an analysis of reliability for the scale of knowledge through the Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 was performed. This formula is used to measure internal consistency when the test items are dichotomous, i.e., coded 1 when it is "correct" and 0 when "wrong" (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). The value obtained for KR-20 was .831, which suggests a significant relationship between the items and the totality of the test. Therefore, the objective of developing a scale that has an acceptable content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) was met. According to Lawshe (1978), the CVR should be greater than .78 and CVI must be greater than .70. It is evidenced that the instrument has a consensus agreement between the expert judges around the relevance of the instrument for the evaluation of the attitude and knowledge that the health professionals of Puerto Rico have towards sexual assault in adult women.The results of the analysis of items for the scale of attitudes indicate that eight items do not adequately discriminate and 18 that do discriminate properly—that is, items which can discriminate between participants who have a negative attitude and those who do not. After deleting the eight items that do not adequately discriminate, a Cronbach's alpha index of .90 was obtained. According to Kline (2000) and De Vellis (2003), this index suggests that there is a significant relationship between the items and the totality of the scale. In order to achieve this, the difficulty index (P) for each item is studied. The difficulty of an item is understood as the proportion of people who respond correctly to a test item. The difficulty level can range from 0.00 to 1.00, where a high number means greater ease of giving the correct answer. Hopkins and Antes (1990) recommended the items that obtain an index of less than .25 difficulty must be eliminated, since they proved to be too difficult. Similarly, those items that turned out to be too easy, from .86 onwards, should be eliminated. Given the results, 24 items that scored less than .25 or higher than .86 were removed. The remaining 11 items had indices of difficulty that fluctuate between .259 and .852. Reliability by division halvesThe scale of attitudes obtained an alpha coefficient of .779 for the first half and .874 for the second half: an index of correlation of r =.791 between forms, reflecting a high correlation (Champion, 1981). The knowledge scale obtained an alpha coefficient of .801 for the first half and .817 for the second half: an index of correlation of r =.729 between forms, also reflecting a high correlation (Sanchez Viera, 2001).The Spearman Brown method was used to correct the effect of the division. When the test is divided into two halves, the amount of reactants decreases (since the amount of items in each half of the test is less than the whole test). This can affect the correlation analysis. The correlation formula of Spearman Brown was used to correct this effect, which produced a coefficient of .883 for the attitudes scale and .843 for the knowledge scale.Error of measurement standardThe standard error of measurement (SEM) is used to establish the degree of confidence placed in a score by administering a test. It is equivalent to the estimated standard deviation of the scores obtained by an individual when administering the same test on different occasions (Kline, 2000). In a normal distribution, 68% of scores is located between the average and standard deviation, and 95% is located between the mean and two standard deviations. The greater the reliability of the instrument, the lower the error (Kline, 2000).Construct validityConstruct validity is the degree in which an assessment tool measures the construct under study. Construct validity was established through the methods of difference of groups, factor analysis and determining the discriminatory power of the test (Kline, 2000). One of the desirable properties that a scale must have is the ability to distinguish between groups of people. Therefore, discriminatory power is defined as the ability of the test to produce a broad spectrum of scores (Kline, 2000). The nonparametric index used to calculate the discriminatory power of the instrument was Ferguson’s Delta formula (Kline, 2000). In other words, it is the ability of the test to differentiate those who have a negative attitude toward sexual assault and those who do not. The expected minimum rate is .90 (Kline, 2000). The scale of attitudes of health professionals toward sexual assault received an index of .80; it can be concluded that it has adequate discriminatory power. The scale of knowledge of health professionals about sexual assault obtained a rate of .79; it can also be concluded that it has adequate discriminatory power. Analysis of factors. An exploratory factor analysis was performed to assess the construct validity of the AKSSAW. Exploratory factor analysis is a technique for data reduction, allowing the simplification of the data to its most important variables (Kline, 2000). For the analysis of factors for the scale of attitudes, Barlett’s test of sphericity and the extent of the sampling adequacy of Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) were initially conducted in order to determine if the items of the scales were sufficiently inter-correlated. Barlett’s test of sphericity resulted in a significant value of 1,311.36 chi-square (df = 153, p <.001). Measurement of the fitness of the KMO sample indicated a result of .843, which is considered adequate. These data indicate that the data matrix is not an identity matrix, suggesting that the items are interlinked, making the analysis of factors interpretable. Analysis of factors - attitudes scale. Factor analysis conducted on the remaining 18 items of the scale of attitudes revealed that there are three components with an Eigen value greater than one, which explain the 60.548 (%) of the variance. Of these, factor 1 contains the greatest amount of items (10 items), explaining the 44.66 (%) variance.The researcher completed a factor analysis with the Varimax rotation to know how many factors the 18 items that discriminate can properly fit. The purpose of the Varimax rotation is to facilitate the interpretation of the components found through analysis of factors. According to Pett, Lackey and Sullivan (2003), one should retain those factors in which the percent of explained variance is equal to or greater than 5% and the Eigen value is greater than 1. As a result of such analysis, three components that explained the 60.54% of the variance were identified.Also, the Cronbach’s alpha index for each of the factors that were obtained through the Varimax rotation is reported. The following table presents each factor with the alpha index.

One of the three components obtained a Cronbach’s alpha index lower than .70. According to Kline (2000) and De Vellis (2003), Cronbach’s alpha index should not be less than .70. Because of this, the researcher assessed the internal scale reliability by eliminating those components of an alpha less than .70. By eliminating the third factor, the AKSSAW was composed of two factors obtaining a reliability of .882 for the first factor index and .761 for the second. The factor analysis performed after eliminating the third component revealed the existence of two components with a value greater than 1, which explain the 53.19% of the variance. The suggestions provided by Pett et al. (2003) regarding the retaining of factors were followed. As result of this, two components were retained that explained the 53.19% variance. The next table presents the total variance explained by the two factors extracted from the rotation.

One of the three components obtained a Cronbach’s alpha index lower than .70. According to Kline (2000) and De Vellis (2003), Cronbach’s alpha index should not be less than .70. Because of this, the researcher assessed the internal scale reliability by eliminating those components of an alpha less than .70. By eliminating the third factor, the AKSSAW was composed of two factors obtaining a reliability of .882 for the first factor index and .761 for the second. The factor analysis performed after eliminating the third component revealed the existence of two components with a value greater than 1, which explain the 53.19% of the variance. The suggestions provided by Pett et al. (2003) regarding the retaining of factors were followed. As result of this, two components were retained that explained the 53.19% variance. The next table presents the total variance explained by the two factors extracted from the rotation.

|

4. Discussion

- Violence as a social problem and public health issue affects thousands of people in the world. Sexual assault as an act of violence has profound effects on the physical and mental health of the survivors (Department of Health, 2007). However, sexual assault is one of the least reported crimes, due to the social stigma that falls on the victims. Several researchers (Campbell, 1998; Ahrens et al., 2007) have studied survivors of sexual assault and how the reaction they receive when disclosing information to another person can affect them. According to López (2009), when this reaction is negative, the victim of sexual assault is potentially re-victimized.There are several studies that have investigated the link between the attitude of the people who provide services to victims of sexual assault and the quality of services provided (Campbell, 1998; Campbell et al., 2001; Collins, 2003; Ahrens, 2008). Corner (1994) indicated that both the beliefs and attitudes of the counselors can affect the authenticity, warmth and empathy that should be present in all therapeutic relationships, thus affecting the quality of services. Given the impact that the attitudes and knowledge about sexual assault have in the conduct and, therefore, in the performance of people, it becomes essential to study the attitudes and knowledge that nurses, social workers and psychologists have toward sexual assault in adult women. The main objective of this research was to build and validate a scale of Attitude and Knowledge toward the Sexual Assault in Adult Women (AKSSAW) in a sample of nurses, social workers and psychologists. It was expected that the AKSSAW could effectively assess the construct under study, discriminating appropriately between the participants with negative attitudes toward sexual assault victims and those with positive attitudes, and between those who do or do not possess the necessary knowledge about sexual assault.Content validity. To develop the AKSSAW, an extensive literature review was conducted. The items were developed using statements related to the attitude and knowledge toward sexual assault in adult women. It should be noted that parts of the scale of attitudes were obtained from the scale to measure attitude toward sexual abuse in a sample of pastors and clinical psychologists developed by Dr. María López with her authorization. The scale was validated in its content by nine expert judges on the subject of sexual assault and test construction. Out of the original 126 items, only those that eight of the nine experts judged as essential were selected.The form of the scale administered to the sample was initially composed of 61 items. After completing an item analysis, eight items of the attitudes scale were eliminated and 11 items were eliminated from the knowledge scale. The new version of the instrument was composed of 42 items.According to De Vellis (2003) and Kline (1998), the characteristics of a good instrument are: (1) internal consistency equal or greater than .70, (2) a low standard error of measurement, (3) evidence of construct validity, and (4) a high discriminatory power. Before deleting the 19 items, the AKSSAW complied with these requirements, so we proceeded to evaluate the psychometric properties of the final scale in order to verify if it had these features.The index of difficulty (P) was calculated for each item on the scale of knowledge. The difficulty level can range from 0.00 to 1.00, where a high number means greater ease of obtaining the correct answer. We eliminated those items that were very easy or very difficult. The instrument retained those items whose level of difficulty is easy, moderate or difficult (Hopkins & Antes, 1990).Likewise, the scale obtained a discrimination index of .79, according to Ferguson’s Delta formula. These results suggest that the instrument has the ability to discriminate adequately between participants who have a negative attitude toward sexual assault and those who do not. It also discriminates between those who possess knowledge about sexual assault in adult women and those who do not. Although the recommended discriminatory index is .90, there is literature that questions how interpretable this index is. According to Terluin, Knol, Terwee, and CW de Vet (2009), Ferguson’s Delta formula of discrimination ignores the error of measurement, and therefore does not distinguish between reliable and unreliable differences. The authors come to the conclusion that Ferguson’s Delta formula of discrimination is a characteristic of a population and does not refer to any useful property of a measuring instrument. In other words, this formula must be taken into consideration when building an instrument, but other statistical measures should be taken into account to determine if the instrument is reliable or not—for example, the index of reliability, difficulty index and factor analysis.Reliability of the instrument. The statistical analyses to which the instrument was subjected produced high rates of internal reliability. The internal consistency of the instrument was evaluated through the method of split half corrected with the Spearman-Brown formula and the method of Cronbach's alpha. The scale obtained a coefficient of correlation considered moderately high (Sanchez-Viera, 2001). The Spearman-Brown method was used to correct the effect of the division, which showed a high reliability coefficient for the scales of attitude and knowledge. This method allows the test division into halves and correlates both parts (Kline, 2000). The advantage is that it requires only one application of the instrument. If the instrument is reliable, the scores of both halves should be strongly correlated. Therefore, it can be inferred that scores on the scale of attitude and knowledge are strongly correlated.The first part consists of the scale of attitudes and the second consists of the scale of knowledge. A proper Cronbach's alpha index was obtained, which points out that the scale of attitudes has an adequate level of internal consistency (Kline, 2005). Similarly, an analysis of reliability was performed for the scale of knowledge through theKR-20 formula. An appropriate value of KR-20 was found, suggesting a significant relationship between the items and the entire test. According to De Vellis (2003), an adequate internal consistency index should not be less than .70, so the index obtained by the EACM is considered adequate, which means that the instrument meets its purpose and measures what it intends to measure. Analysis of factors. The AKSSAW version of the resulting analysis of biserial discrimination underwent an exploratory factor analysis. This was done with the purpose of simplifying data and pointing out the most important variables (Kline, 2000). The scale of attitudes initially yielded three components when it was subjected to factor analysis with Eigen values greater than 1. An orthogonal rotation of factors, using the Varimax method, was completed to facilitate the interpretation of the data obtained in the factor analysis. However, one of the factors obtained a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient lower than expected. Therefore, it was decided to eliminate this factor in order to determine the reliability of the scale. The AKSSAW was composed of two factors with a reliability index of .88 for the first factor and .76 for the second. We performed a factor analysis in order to assess the construct validity of the AKSSAW by eliminating the component mentioned earlier. The analysis revealed the existence of two components with Eigen values greater than 1, which explains the 53.19% of the variance.The results indicated that the final AKSSAW maintained the expected psychometric properties., with a Cronbach’s alpha of .90, standard errors of measurement for the scale of attitudes of 0.50 and for scale of knowledge .29, and discriminatory power of .79 for the scale of attitudes and .78 for the scale of knowledge. The AKSSAW is a reliable and valid instrument to measure the attitude and knowledge of health professionals toward sexual assault in adult women. The final scale (Spanish version) is presented in Appendix A and consists of 18 items that evaluate attitudes and 11 items that evaluate knowledge. Scale cut points are as follows for the attitude part: 18-45 points demonstrate a highly prejudiced attitude about sexual assault, 46-60 demonstrate a moderately prejudiced attitude about sexual assault, and finally 61-72 demonstrate no prejudiced attitude about sexual assault. The knowledge section cut points are as follows: 0-10 indicate poor knowledge, 11-18 indicate moderate knowledge, and finally 19-24 demonstrate a profuse knowledge related to sexual assault. Use and application of the instrumentThe Scale of Attitudes and Knowledge of Health Professionals toward Sexual Assault in Adult Women (AKSSAW) is considered valid according to the psychometric data obtained in this study. Its use is aimed at evaluating the attitudes and knowledge of health professionals in Puerto Rico toward sexual assault in adult women. Its application is to obtain information on attitudes and knowledge that the health professionals have toward sexual assault, using such measures as acceptance of myths and knowledge demonstrated through the literature on sexual assault.

5. Conclusions

- This research contributes to the progress and development of sensitive instruments to the Puerto Rican population. Its use is intended to reveal the attitudes and knowledge that the health professionals have regarding sexual assault, with the purpose of evaluating the acceptance of myths and knowledge toward sexual assault which continue in our culture.

6. Recommendations

- Using the final version of the instrument, it is recommended that the process of validation of the scale be replicated using a larger sample. We encourage the type of sampling to be a probabilistic one, where all elements of the population have an equal chance of being selected (Sanchez Viera, 2001). Also, researchers are invited to replicate the study using other health professionals providing services to adult women who are victims of sexual assault such as gynecologists, psychological counselors, etc., in addition to completing a confirmatory analysis of those results.Researchers are encouraged to review those items of the scale of knowledge with "easy" or "difficult" levels. According to Hopkins and Antes (1990), the items that are easy or difficult must be revised. It is recommended that the stability of the instrument be evaluated through a test re-test approach. In the same way, we encourage the studying of the attitudes and knowledge of health professionals.

7. Limitations

- Among the limitations of study is the type of sample used, which was by availability. Because of this, the generalization of the findings is limited to the participants of this study. The next apparent limitation is that in terms of the total sample 85.5% (n = 115) were women and only 14.8% (n = 20) were men. This is considered a limitation since gender inequity affects the testing of the hypotheses raised initially. Another limitation is that 17.8% (n = 24) of the 135 participants left items unanswered, which could affect the results, so the process of validation of the AKSSAW should be considered a preliminary one.

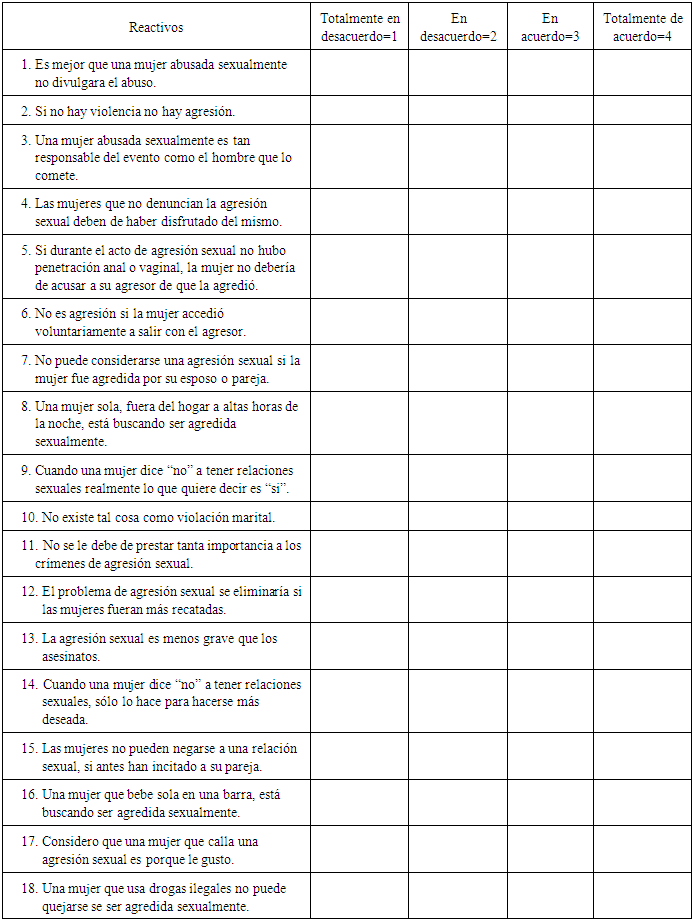

Appendix A

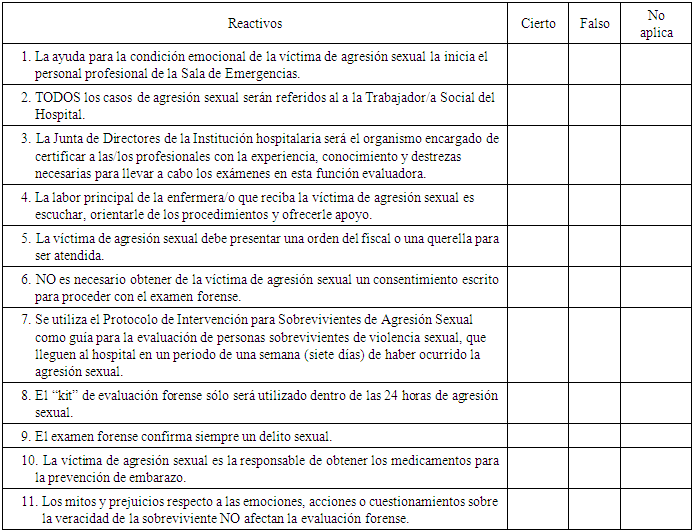

- AKSSAW SCALE (Spanish Version): Sección de Actitud de los Profesionales de la Salud hacia la Agresión Sexual en Mujeres Adultas: Instrucciones: El presente instrumento es la forma preliminar de la Escala de actitud y conocimiento de los profesionales de la salud hacia la agresión sexual en mujeres adultas. Es importante que contestes el mismo con la mayor sinceridad posible. Las preguntas demandan que marque con una “X” la respuesta adecuada.

AKSSAW SCALE (Spanish Version) : Sección de Conocimiento de los Profesionales de la Salud hacia la Agresión Sexual en Mujeres AdultasInstrucciones: El presente instrumento es la forma preliminar de la Escala de actitud y conocimiento de los profesionales de la salud hacia la agresión sexual en mujeres adultas. Es importante que contestes el mismo con la mayor sinceridad posible. Las preguntas demandan que marque con una “X” la respuesta adecuada.

AKSSAW SCALE (Spanish Version) : Sección de Conocimiento de los Profesionales de la Salud hacia la Agresión Sexual en Mujeres AdultasInstrucciones: El presente instrumento es la forma preliminar de la Escala de actitud y conocimiento de los profesionales de la salud hacia la agresión sexual en mujeres adultas. Es importante que contestes el mismo con la mayor sinceridad posible. Las preguntas demandan que marque con una “X” la respuesta adecuada.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML