-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(3): 161-166

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160603.10

Factors Affecting Teaching and Learning in Mother Tongue in Public Lower Primary Schools in Kenya

Charles Onchiri Ong’uti 1, Peter J. O. Aloka 2, Pamela Raburu 3

1Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

2Psychology and Educational Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

3School of Education, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Peter J. O. Aloka , Psychology and Educational Foundations, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Kenya has legislated a Language in Education (LiE) policy to use mother tongue in lower primary classes (class 1-3), yet the pupils in Tabaka Division of Kenya continue to perform poorly in national examinations. The purpose of this study was to investigate factors affecting teaching and learning in mother tongue in lower public primary schools in Kenya. The Chomsky’s theory of language acquisition was adopted. The study employed the sequential triangulation research design within the mixed methods approach. Questionnaires for teachers were used to collect quantitative data while qualitative data was collected using interview schedules, focus group discussions (FGDs) and observations. The validity of instruments was ensured by expert judgment by university lecturers while reliability was ensured by external consistency and a coefficient of r = 0.775. The target population comprised of 6000 pupils, 170 teachers, 17 head teachers, and 10 parents out of whom 90 pupils, 9 head teachers, 9 class three teachers, 10 parents and 1 Education Officer were sampled. Saturated sampling technique was used to select the head teachers, the primary schools, and class 3 teachers of lower primary, while simple random sampling was used to select the learners. Descriptive statistics was used to analyze quantitative data while interview data was analyzed using Thematic Analysis. The study reported that both teachers and learners had negative attitudes towards teaching and learning in mother tongue. The study recommended that relevant education players develop a curriculum which would result in the use of local languages as tools for economic empowerment and help change the attitudes of teachers, learners and parents towards teaching and learning in mother tongue.

Keywords: Teacher and learner factors, Teaching and learning, Mother tongue, Lower public primary schools, Kenya

Cite this paper: Charles Onchiri Ong’uti , Peter J. O. Aloka , Pamela Raburu , Factors Affecting Teaching and Learning in Mother Tongue in Public Lower Primary Schools in Kenya, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 161-166. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160603.10.

1. Introduction

- In 1948, the United Nations (UN) declared education a human right (UNESCO, 1995). From 1990 and more so since 2000, the goal of Education For All (EFA) by 2015 triggered many countries in sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) to roll out programmes through constitutional changes to achieve Universal Primary Education (UPE) for their citizens in line with the World Conference on Education for All (EFA) in Jomtien, Thailand in 1990, (UNESCO, 2005). These programmes have remarkably attracted hundreds of children into schools (UNESCO, 2008) in an endeavor not to just fill classrooms with children, but to bring positive social and economic consequences by enabling children to acquire basic competencies in literacy and numeracy so they could gain from and contribute to the future of their societies. The debate on which language to use to provide quality education to the pupils, especially in the early years of education, has gone on for decades in many countries. Mother tongue based instruction (MTBI) is instruction given in a child’s first (home) language (L1). Studies from different parts of the world indicate that MTBI has benefits that enable pupils to achieve more highly than when education is provided in a second language (L2), usually the colonial language or a national language (NL) widely spoken and understood by most of the pupils in that country (Kagure, 2010). However, the implementation of the above policy has been hampered by a several factors (Mulatu, 2014).Furthermore, for the non-French speakers, mother tongue was taught outside school hours and usually by a teacher of foreign nationality who would have difficulty to make links with other subjects or even to communicate with permanent school staff. While foreign language teaching (FLT) was meant for cognitive, economic, social and cultural reasons, marginalized language teaching (MLT) was meant to be useful when the children eventually returned to their countries of origin and needn’t be taught in school. Consequently, teachers developed a negative attitude towards mother tongue and believed that speaking these languages at home delayed the acquisition of French (Helot and Young, 2002). In Kenya there has been and continues to be inter-tribal migration (Benson, 2005). In Senegal, West Africa, Klass, (2008) study showed that pupils who were instructed the in home language (L1) performed much better than those who were instructed in French (L2). Oribabor and Adesina, (2013) also in Nigeria found out that instruction in mother tongue aided learning better than English language as a medium of instruction in nursery school.The study is guided by the Language Acquisition theory of the linguist philosopher and cognitive scientist Chomsky, (1999). According to Chomsky, (1999) children have got inborn structures in the brain he referred to as Language Acquisition Devices (LAD) that give them a natural propensity to organize spoken language in different ways, and argued that children do not simply copy the language that they hear around them, (a view proposed by Skinner, (1997) in his social learning theory in Touretzky and Saksida, (1997) but that they deduce rules from it, which they can then use to produce new sentences. Further Chomsky, (1999) argues there is a universal syntactic set of categories, he called universal grammar (UG) or “language faculty” which children are born with which help them to learn how words and structures of their first language are related to elements of Universal Grammar. The Language Acquisition theory informed the present study in that if children are not fluent in their mother tongue in oracy and literacy their vocabulary becomes limited, and this restricts their ability to learn a second language and so become illiterate in both mother tongue and the second language. Therefore, a strong foundation in mother tongue is needed for learning the second language, and when teachers and pupils understand this they will be positive towards the use of mother tongue for teaching and learning.Burton, (2013) indicated that teachers’ and parents ‘views of MTB-MLE focused on the short-term benefits of the policy and the long-term disadvantages. Lefebvre, (2012) revealed that the students did not have an overwhelmingly negative attitude towards the use of mother tongue for instruction; however, their attitudes seemed to fall somewhere between their learned value for multilingualism and their lived experiences. Kiziltan and Atli, (2013) revealed that the pupils had developed positive attitudes towards English language skills and sub skills, materials, the course books, and activities. Further, it was established that the attitudes of the pupils changed significantly according to language skills and learning environment. However, there was no significant difference in the attitudes of pupils towards English according to gender. Chivhanga and Chimhenga, (2014) revealed that the success of using Chishona as a medium of instruction depended on the attitudes and will of the teacher to actually implement it. The study also revealed that the teachers, parents and pupils had negative attitudes towards the use of Chishona as a medium of instruction for mathematics. Ngidi, (2007) revealed that while parents and pupils had a positive attitude towards the use of English as a language of learning and teaching and an additional language in schools, the educators had a negative attitude towards English as a language of learning and teaching and as an additional language in schools. Khenjeri, (2014) revealed that mother tongue was less valued than English which has instrumental and integrative purposes. Begi, (2014) established that fewer pre-primary school teachers and lower primary school teachers were using mother tongue as a Language of Instruction, while most of pre-primary school and of lower primary school teachers were not using mother tongue as a Language of Instruction.Kenya introduced FPE in 2003 resulting in an increase in enrollment by over one million (17.6%). The language in Education (LiE) policy in Kenya advocates the use of mother tongue instruction in lower primary classes 1 –3. It states in part: “The language of the catchment area (mother tongue) shall be used for child care, pre-primary education and in the education of lower primary children (RoK, 2012). However, this has not been achieved as many schools have continued to use L2 from as early as pre-school, citing a number of factors particularly the large number of languages in Kenya (Benson, 2005). There are over 70 languages and dialects in Kenya which divide Kenyans into regional sub-groups but there is continued inter-regional movement and migration of its people such that one would find children in rural schools who do not speak the language of that community (Benson, 2005). Parents have also put pressure on school managers and teachers to introduce English to their children in these early years of learning. This notwithstanding, English is more commonly used in schools and urban areas. “Sheng”, a mixture of English, Swahili and Vernacular is a popular identity marker among the youth but is gaining its way into the larger society (Benson, 2005; and Ogechi, 2005).The need for this study was informed by the concerns raised by the Kisii Council of Elders which observed that the “Ekegusii language may die out in the next 50 years” (Matundura, 2015). This is because more than half of the community members below 20 years of age do not speak the language while those members living in the diaspora and in towns would rather speak English and Kiswahili. Further, an Education Conference was held at Kisii University in August 2014 with the theme “Africa and the New World Order” which sort to explore ways of providing quality education to the pupils in Kisii County so as to tackle the perennial poor performance by primary school pupils in this region. In monitoring and assessment reports by KNEC, (2010) and UWEZO, (2010; 2011; 2012) already referred to earlier, in which Gucha and Kisii were among the districts surveyed it was found that a vast majority of primary school pupils were not acquiring basic literacy and numeracy competencies and were therefore performing poorly in national examinations – a pointer to the importance of mother tongue as a language of learning in the early years of education of pupils.

2. Methodology

- The Concurrent Triangulation was adopted to inform the study. The design shows that quantitative and qualitative data were collected at approximately the same time. Quantitative data were collected followed by qualitative data collection. The quantitative data were then analyzed followed by the analysis of qualitative data. The two results were compared and integrated during the interpretation phase so as to strengthen the understanding of the research questions that were being investigated. The target population comprised of 6000 pupils, 170 teachers, 17 head teachers, and 10 parents out of whom 90 pupils, 9 head teachers, 9 class three teachers, 10 parents and 1 Education Officer were sampled. Saturated sampling technique was used to select the head teachers, the primary schools, and class 3 teachers of lower primary, while simple random sampling was used to select the learners. The validity of instruments was ensured by expert judgment by university lecturers while reliability was ensured by external consistency and a coefficient of r = 0.775.

3. Results & Discussion

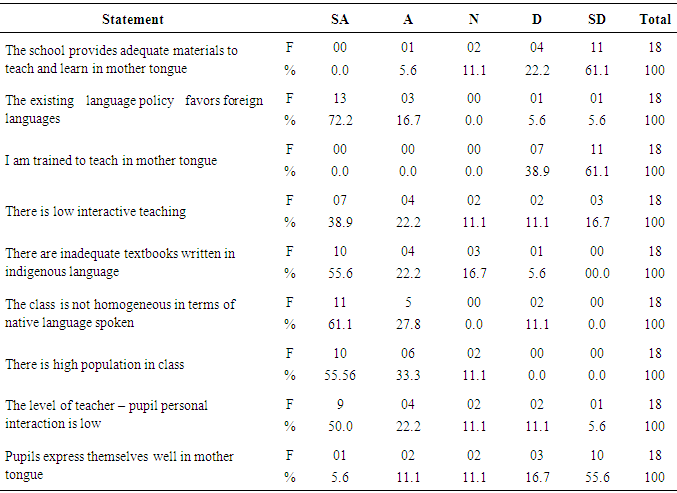

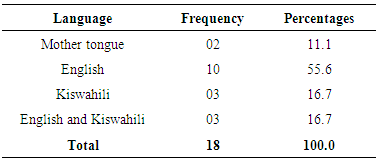

- In investigating factors affecting the respondents (teachers and head teachers) were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the following statements. Where SA= strongly agree; A= agree; N=neither agree nor disagree; D=Disagree; SD=Strongly Disagree. The findings are presented in table 1.

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The study concluded that; both teachers and learners had negative attitudes towards teaching and learning in mother tongue. The study also concluded that poor attitude of teachers towards mother tongue and preference of foreign languages as a mode of communication, could be attributed to lack of proper training among the teachers and the unavailability of resources for teaching and learning in mother tongue, while learners’ preference for English and Kiswahili could be attributed to their prominence as languages of education and greater communication. The study recommended that, the primary teacher training colleges in Kenya should be empowered to train and in-service teachers in mother tongue skills since they are the ones mandated to produce the bulk of professional teachers for primary schools in Kenya. This is because the study revealed that primary school teachers were not trained the skills of teaching Mother Tongue. Further studies could focus on the Influence of foreign languages on adoption of mother tongue in education.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML