-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(3): 99-102

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160603.01

Attitude and Gender as Predictors of Insurance Loyalty

Steven A. Taylor

Department of Marketing, Illinois State University, Normal, USA

Correspondence to: Steven A. Taylor , Department of Marketing, Illinois State University, Normal, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Financial services marketing issues related to consumer loyalty with insurance products continues to grow in both importance and challenge, none-the-less, remain poorly understood. A scenario-based study is presented that empirically validates via structural equation-based mediation analyses existing arguments that (1) both cognitive and affective considerations affect consumer decision-making vis-à-vis loyalty intentions to auto insurers post-poor service delivery, and (2) these considerations vary by gender. The research and managerial implications are presented and discussed.

Keywords: Attitude, Insurance, Loyalty

Cite this paper: Steven A. Taylor , Attitude and Gender as Predictors of Insurance Loyalty, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 99-102. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160603.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Financial services marketing issues related to consumer loyalty with insurance products continues to grow in both importance and challenge, none-the-less, remain poorly understood. [1] Taylor (2013 [1]) presents empirical results supporting the conclusions that (1) both cognitive and affective considerations are important to consumer judgment and decision-making (J/DM) processes with car insurance, and that male and female customers may vary their J/DM processes in automobile insurance settings. The current study more deeply explores the J/DM processes of adult automobile consumers in the United States through mediation analyses (MacKinnon, 2008 [2]; Hayes, 2013 [3]).

2. Study Methods and Results

- Automobile insurance is a risk-related product category. Previous research has indicated that gender is a predictor of risk taking that reveals itself in neither a straightforward nor stable manner -- but instead varies across age and context (Byrnes, Miller, and Schafer, 1999 [4]). We present evidence to help inform these issues via consideration of an (abbreviated) attitude-based model of J/DM per Taylor (2013).

2.1. Research Model and Hypotheses

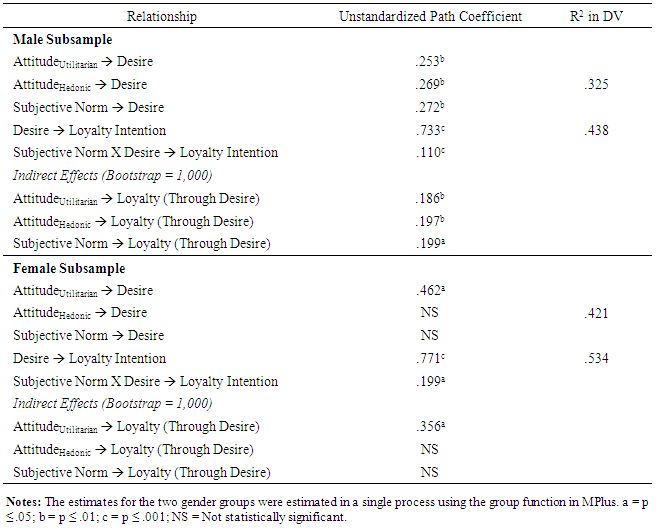

- Figure 1 presents the research model considered herein. In short, our expectation can be expressed as seven research hypotheses based upon the cited research as follows [1, 5]:H1: The psychological decision model underlying the formation of loyalty intentions to automobile insurers generally varies by gender.H2: The desire to remain loyal to an auto insurer is positively related to hedonic attitudes. H3: The desire to remain loyal to an auto insurer is positively related to utilitarian attitudes. H4: The desire to remain loyal to an auto insurer is positively related to subjective norms. H5: Desire fully mediates the relationship between hedonic attitudes and the intention to remain loyal to an automobile insurer.H6: Desire fully mediates the relationship between utilitarian attitudes and the intention to remain loyal to an automobile insurer.H7: Desire fully mediates the relationship between subjective norms and the intention to remain loyal to an automobile insurer.

| Figure 1. The reserch model |

2.2. Research Methods

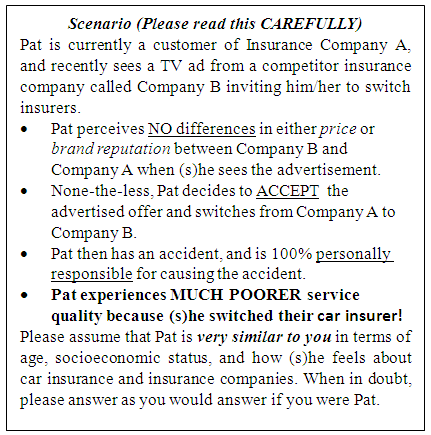

- The study involved a regionally mail-based survey to adults. The sampling frame was purchased from an external body, and 7,000 surveys were sent to random adults in the county of the university of the researcher. A new $1 was included in each physical mailing to encourage response. The data were analyzed using SPSS and Mplus. SPSS was used to identify data description, whereas MPlus was used to conduct confirmatory factor analyses to validate measurement models, empirically test the predictive structural model associated with Figure 1, and conduct the mediation/moderation analyses based upon the recent innovation in Mplus related to mediation analyses [6]. The research was scenario-based to (1) encourage response by reflecting a third-party intention, and (2) minimize potential confounding of results associated with potential inaction-effect bias [7]. Inaction effect bias involves the frequent phenomenon that decisions to act (i.e., actions) produce more regret than decisions not to act (i.e., inactions). Specifically, Tsiros and Mittal (2000 [12]) present results suggesting that (1) regret specifically influences repurchase intentions (the context of the current research), and (2) the generation of counterfactuals important to regret perceptions are most likely to be generated when the chosen outcome is negative and not the status quo in consumer choice models. This jibes with Taylor’s (2013 [1]) arguments related to personal responsibility and status quo choices in choice models in consumer loyalty decisions to automobile insurers. Consequently, our scenario (see Figure 2) included both a change in status quo as the result of a consumer decision to change insurers in response to an advertisement, and then an outcome that suggested a measure of personal responsibility (see the scenario below).

| Figure 2. The Scenario Used in the Current Research |

2.3. Study Results

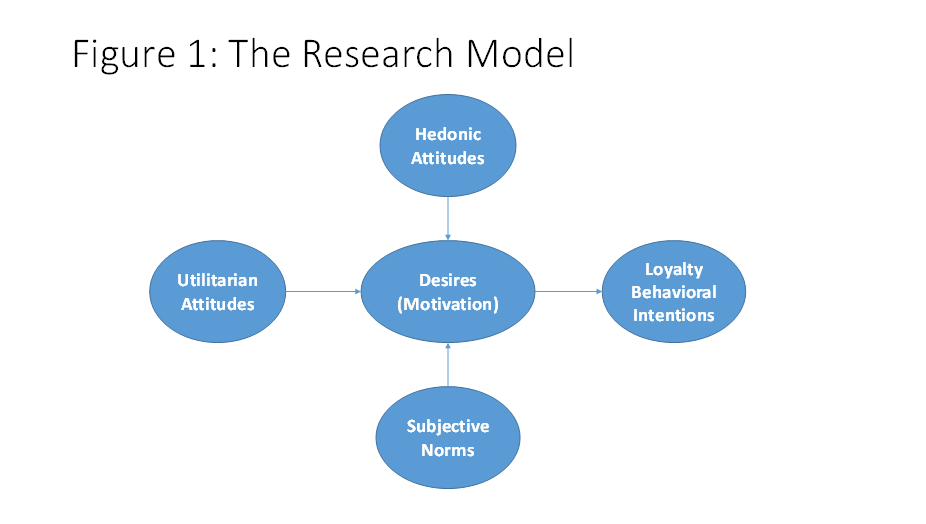

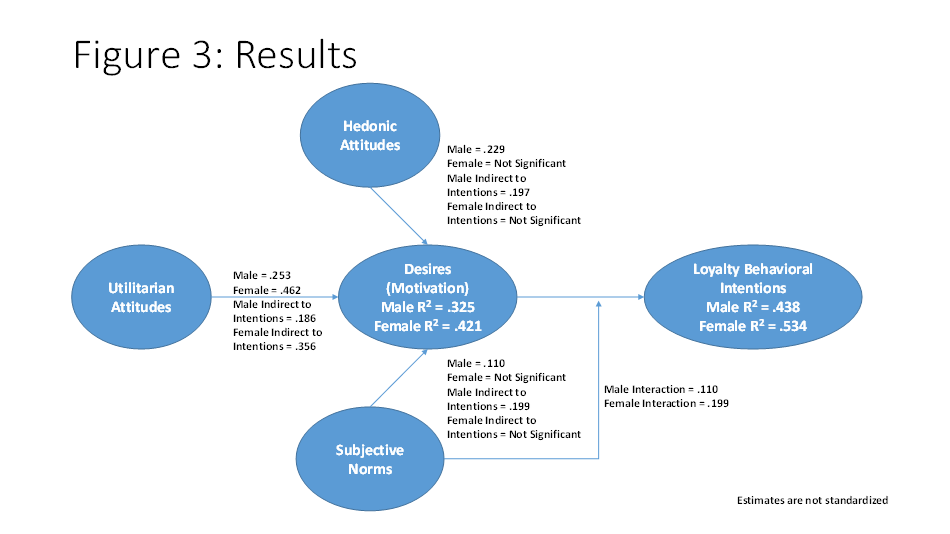

- Close to 750 usable surveys were returned, representing a response rate of over 10%. However, since the research project involved additional research questions that required two unique survey instruments (i.e., this is part of a larger study), the data supporting the research reported herein was based upon a subset of 368 usable responses (247 males and 121 females). The respondents’ ages ranged from 30-90 years of age. The respondent pool is best characterized as being generally loyal to their automobile insurers with 85% of males and 69% of females expressing that they have had an ongoing relationship with their current automobile insurer for at least the last four years.Appendix A presents the measures used in the study, which are all derived from previous studies. Confirmatory factor analyses using the group analysis function (by gender) of MPlus support the conclusion that the measurement model is sufficient to test the structural model presented as Figure 1 based upon (1) overall fit indices (χ2 = 528.423, df = 276, RMSEA = .066, CFI = .961, TLI = .957, SRMR = .061), and (2) construct reliability and validity indices (see Appendix A). The test of the structural model also supports interpretation of the predictive results (χ2 = 500.399, df = 282, RMSEA = .069, CFI = .958, TLI = .954, SRMR = .079). Table 1 and Figure 3 presents the results of predictive analyses, including mediation analyses using the Group, Interaction, and Indirect functions of MPlus.

3. Discussion

- The results of mediation/moderation analyses are insightful. H1 is the general hypotheses tested herein that the underlying psychological model leading to loyalty intention formation after a negative insurance event varies across gender. The evidence in Figure 3 and Table 1 support this hypothesis. All of the remaining research hypotheses received either complete or mixed (by gender) support in our empirical analyses. While both male and female respondents expressed direct, indirect, and interactive relationships underlying the formation of the motivation and subsequent intentions to be loyal to an insurer after a “poor” outcome, there are noticeable specific differences. First, and surprisingly, hedonic attitudes proved influential (both as direct and indirect influences) in the J./DM model considered herein for males, but not for females. While we can only speculate as to the specific reason for these observed results, Wang (2010 [13]) argues that while emotion is an important variable affecting risk-related decision making, how emotion operates in these is still an unsolved problem. Wang (2010) presents empirical results demonstrating that relative to males, females appear inclined to be risk adverse. This would explain the reliance of females in the sample obtained herein more so on volitional cognitive constructs like AttitudeUtilitarian over AttitudeHedonic.

| Figure 3. Results |

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This research was funded through a grant from the Katie Insurance School of Illinois State University. The Appendix A survey items are available upon request from the author at (staylor@ilstu.edu).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML