-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(2): 82-90

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.08

Depression as Indicator of Emotional Regulation: Overgeneral Autobiographical Memory

Hwiyeol Jo 1, Yohan Moon 2, Jong In Kim 3, Jeong Ryu 4

1Department of Computer Science & Engineering, Seoul National University, South Korea

2Department of Interactional Science, Sungkyunkwan University, South Korea

3Interdisciplinary Program in Cognitive Science, Seoul National University, South Korea

4Department of Psychology, Yonsei University, South Korea

Correspondence to: Hwiyeol Jo , Department of Computer Science & Engineering, Seoul National University, South Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Autobiographical memory encompasses our recollection of specific, personal events. In this study, we investigate the relationship between emotion and autobiographical memory, focusing on two broad ways in which these interactions occur. First, the emotional content of an experience can influence the way in which the event is remembered. Second, emotions and emotional goals experienced at the time of autobiographical retrieval can influence the information recalled. We examined the specificity of undergraduate students in autobiographical memory retrieval. Undergraduate students (N=64) completed the Autobiographical Memory Test (J.M.G. Williams & K. Broadbent, 1986), psychological state; depression (Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression, Radloff, 1977), present affective (Positive Affective and Negative Affective Schedule, Watson et al., 1988) as well as personal factors; life orient (Life Orient Test, Scheier & Carver, 1985), self-awareness (Core Self Evaluation Scale, Judge et al., 2003), social factor (Social Support, Sarason et al., 1983). Results showed that individuals with depression were significantly less specific in retrieving negative experiences, relative to control groups of low depression. This result was restricted to negative memory retrieval, as participants did not differ in memory specificity for less emotional experiences. These results show that repressors retrieve negative autobiographical memories in an overgeneral way, possibly in order to avoid retrieving negative experience.

Keywords: Autobiographical Memory, Story Grammar, Overgeneral Memory, Emotion, Depression

Cite this paper: Hwiyeol Jo , Yohan Moon , Jong In Kim , Jeong Ryu , Depression as Indicator of Emotional Regulation: Overgeneral Autobiographical Memory, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 82-90. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.08.

1. Introduction

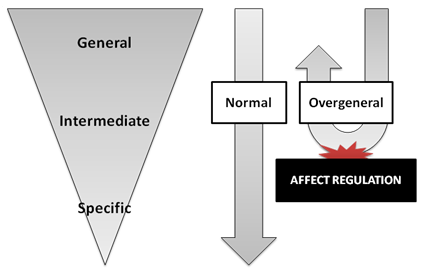

- Autobiographical memory (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000) encompasses our recollection of specific personal events. Autobiographical memory is affected by the emotional status of the person recollecting the memory and the content of the experience. Past research found that there are differences in autobiographical memory between people who have emotional disorders and those who do not. For example, Williams & Broadbent (1986) focused on people who attempted suicide, Rose Addis & Tippett (2004) on patients with Alzheimer disease and Williams et al. (2007) on people with emotional disorders. These studies concluded that autobiographical memory manifests differently in people with emotional disorders than in those with normal emotional health. They revealed that autobiographical memory in patients with disorders seems to be overgeneralized.The overgeneral memory refers to a tendency to retrieve memories only in generalized ways. People exhibit an inability to retrieve specific memories. Some research explained that these people want to avoid remembering the previous painful experience, which is called affect regulation, so they describe their memories in abstract and general (Raes et al, 2003). If this retrieving style continues long term, people can suffer mnemonic interlock, destroying the indices for memory retrieval (Williams, 1996).

2. Methods

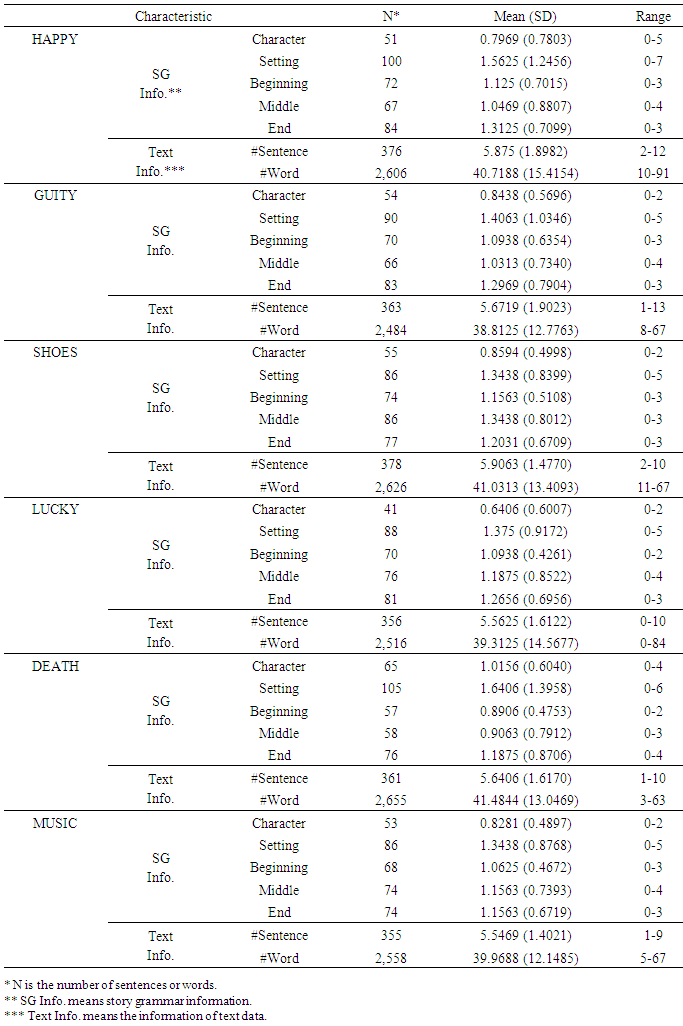

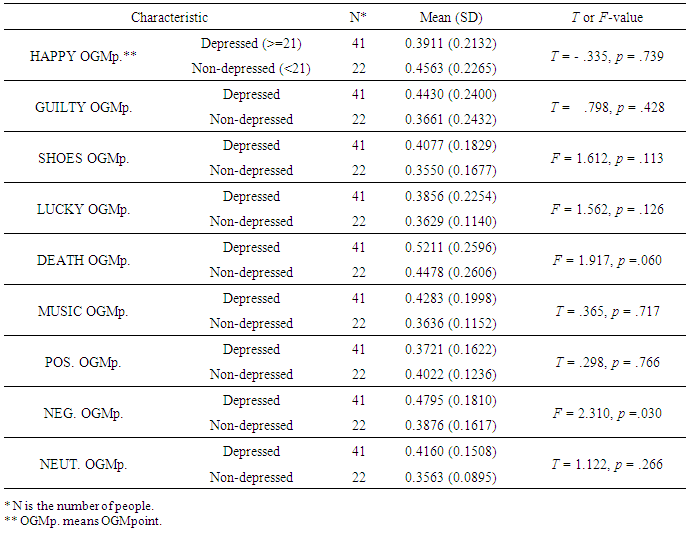

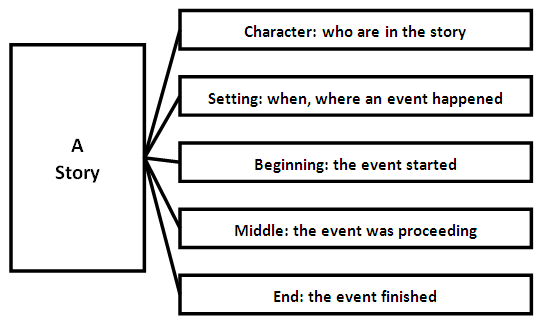

- We examined the relationship between reduced specificity in autobiographical memory retrieval. The subjects of the experiment were undergraduate students (N=64) enrolled in “Introduction to Cognitive Science” class for the 2014 fall semester in Konkuk University, Korea. The participants consisted of 39 men and 25 women and their age distribution between 20 and 29, except for one participant who was 30 years old. 30 subjects were liberal arts majors and the other 34 majored in sciences.After their midterm exams, they first completed their psychological state; depression (Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression, Radloff, 1977), present affective (Positive Affective and Negative Affective Schedule, Watson et al., 1988) as well as personal factors; life orient (Life Orient Test, Scheier & Carver, 1985), self-awareness (Core Self Evaluation Scale, Judge et al., 2003), social factor (Social Support, Sarason et al., 1983). In the following week, they completed the Autobiographical Memory Test (Williams & Broadbent, 1986). We presented the cue words, ‘행복’ (HAENG-BOK means happy), ‘가책’ (GA-CHAEK means guilty), ‘신발’ (SIN-BAL means shoes), ‘행운’ (HAENG-UN means lucky), ‘죽음’ (JUK-UM means death), ‘음악’ (UM-AK means music) in order of positive, negative, and neutral connotations. Participants were given one minute for each cue word to write down an episodic memory.After the tests, we differentiated the autobiographical memories by Marshall’s story grammar (Marshall, 1983), analyzing it as descriptive statics, frequencies and t-test using SPSS 22.0.Story grammarStory grammar was made for students to help them to understand literatures. It is consist of 5 parts, character, setting, beginning, middle and end. We developed the idea that by analyzing the AMT data using Marshall’s story grammar format, overgeneral memory among the participants would be distinguishable. We considered that the overgeneral memory would be more concentrated on the earlier parts of story grammar than the latter part because they cannot follow the ordinary process of memory retrieval, general, intermediate step without specific (Conway, 2005). Measurement(i) LOT (Life Orientation Test)To determine whether a person is optimistic or pessimistic, Scheier & Carver (1985) invented LOT. LOT is closed-question set of personal positive or negative characteristics. Each question has 0-4 scale and the degree of scores means that the intension of agree or disagree. 0 is strong disagree, 1 is disagree, 3 is agree, and 4 is strong agree.

| Figure 2. N. Marshall’s Story grammar: a story can be divided into 5 parts |

3. Results

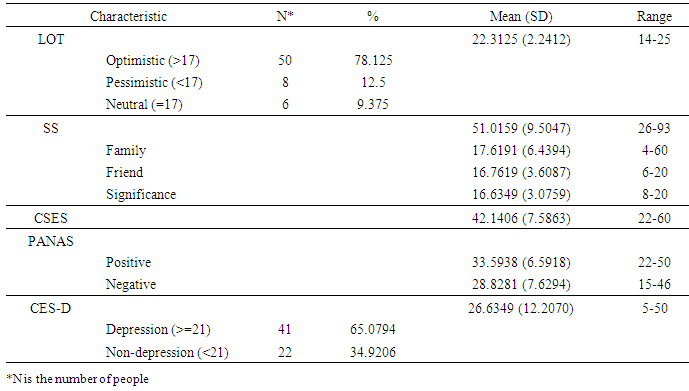

- General InformationParticipantsMost of participants were in 20s and university students. 19 (29.69%) students were 20 years old, 13 of them (20.31%) 21 years old, 6 of them (9.38%) 22 years old, 8 of them (12.5%) 23 years old, 5 of them (7.81%) 24 years old, 5 of them (7.81%) 25 years old, 5 of them (7.81%) 26 years old, 2 of them (3.13%) was 27, and only one of them (1.56%) 30 years old student. The mean and standard deviation of ages was 22.31 and 2.36, respectively. This allows for a group of well controlled samples in terms of how much depression they feel dependent to their age.Participants were distributed evenly by gender and department. There were 39 (60.94%) men and 25 (39.06%) women. 31 (48.44%) students were major in liberal arts while the others (51.56%) were major in science.Given the culture, we were worried about the distribution that gender is strongly related to department vice versa, but fortunately, they were not biased. Men who majored in art were 17, whereas majored in science were 22. Women who majored in art were 14 and in science were 11.Psychological StatusThe psychological status, LOT, SS, CSES, PANAS, CES - D, of the undergraduate students is presented in table 1.

|

|

|

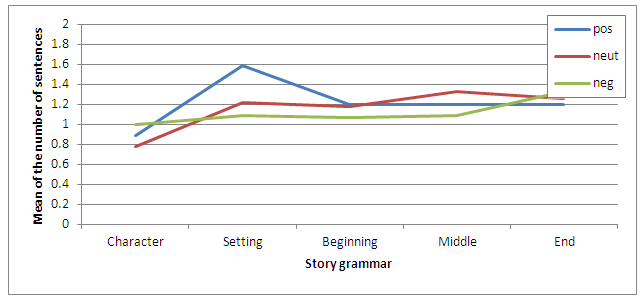

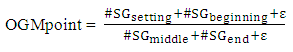

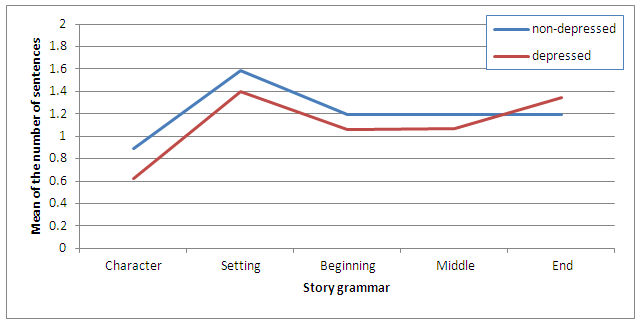

| Figure 3. The mean of the number of story grammar in non-depressed |

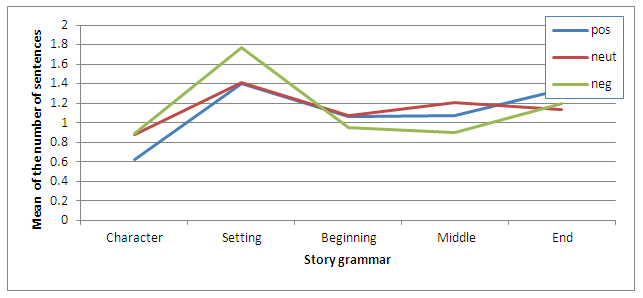

| Figure 4. The mean of the number of story grammar in depressed |

| (1) |

is small number to prevent the value from dividing by zero.

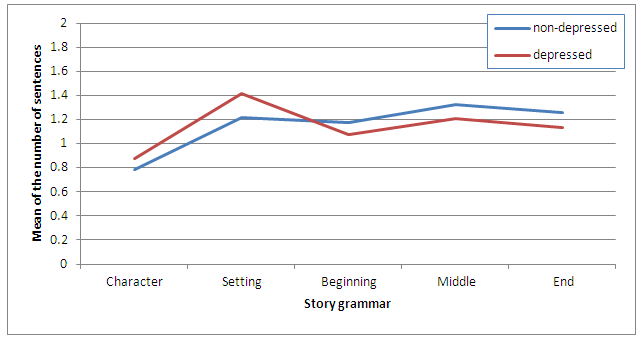

is small number to prevent the value from dividing by zero. | Figure 5. The mean of the number of story grammar in positive words |

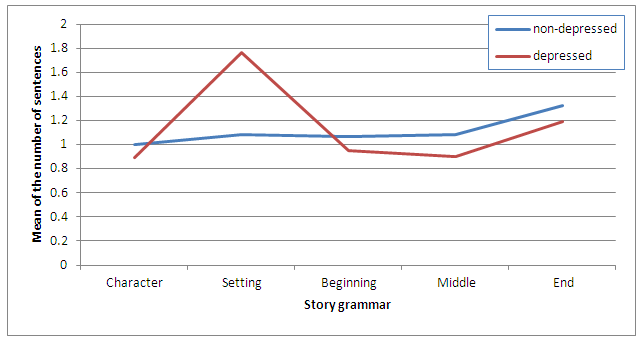

| Figure 6. The mean of the number of story grammar in neutral words |

| Figure 7. The mean of the number of story grammar in negative words |

|

, we assigned it to

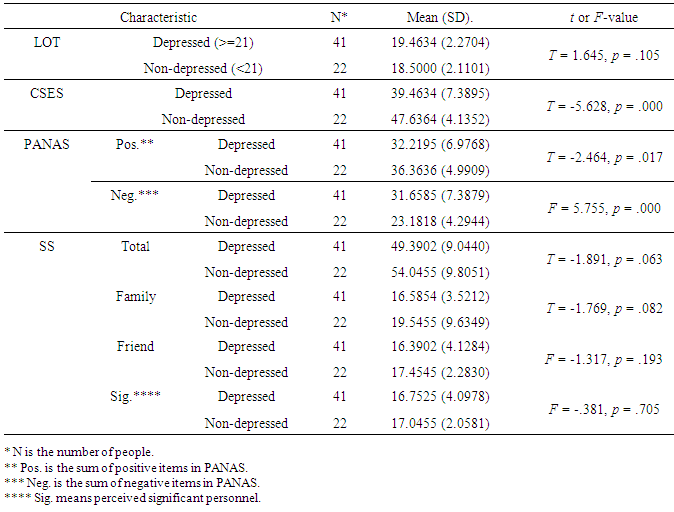

, we assigned it to  , for weighting OGMpoint if the sum of the number of story grammar is high but concentrated on setting and beginning part.We could observe a significant difference in OGMpoint between depressed (M=0.4795, SD=0.1810) and non-depressed (M=0.3876, SD=0.1617) in negative words; F(55.287)=2.310, p=.030.

, for weighting OGMpoint if the sum of the number of story grammar is high but concentrated on setting and beginning part.We could observe a significant difference in OGMpoint between depressed (M=0.4795, SD=0.1810) and non-depressed (M=0.3876, SD=0.1617) in negative words; F(55.287)=2.310, p=.030.4. Conclusions

- We examined the relationship between emotion and autobiographical memory: First, the emotional content of an experience can influence the autobiographical memory. Second, the psychological status can also influence the autobiographical memory. We hypothesized that the difference would be distinguishable from the specificity of autobiographical memory, so we split the autobiographical memory by N. Marshall’s story grammar format. We used CES-D with cut-off point 21 to divide undergraduate students into two groups, “depressed” and “non-depressed”. We defined OGMpoint to observe overgeneralized memory.The result shows that depression is strongly related to other psychological status; depressed people felt less core-self evaluation than non-depressed in CSES. Also, they were less positive, and more negative in PANAS. SS results indicate that they couldn’t feel enough supports from their environments. Next, we observed differences in story grammar. When people who scored high in CES-D recalled negative experience, they tended to more focusing on setting and beginning part of the story grammar than the others, getting high scores in OGMpoint, which means overgeneralized their memories are. But the tendency was not shown in positive and neutral memories. Therefore, we can explain the results as affect regulation to avoid retrieving negative experience.There are several weak points in our experiment methods: First, even though the participants are in 20s, enjoying their current campus life, their CES-D scores were too high when compared to other experiments. Approximately over half of subjects were depressed. The reason seems that the time when we gave them questionnaires was the following week from mid-term exam. Second, three of the participants were foreigner so their writing skill was scanty. We could regard them as outlier. However, we could not distinguish that the autobiographical memory of others looked overgeneralized because of depression or poor writing skills. Plus, a student insincerely responded to some questionnaire. Third, the OGMpoint should be complemented. The original formula had a probability to be divided by zero, which would be regarded as an error (or blank) in SPSS. Therefore, we introduced

to avoid the error. However, the calculation can be greatly different by

to avoid the error. However, the calculation can be greatly different by  . If

. If  is too big, the calculation error will be increased. If

is too big, the calculation error will be increased. If  is too small, the value of OGMpoint will be huge, and then it will destroy the overall characteristics of OGMpoint. There has been no reference and previous research to deal with autobiographical memory as story grammar format. A contribution of this research is the first approach to formulate the overgeneral memory using combination of autobiographical memory with story grammar. If the methods are modified and improved through additional research, it will be powerful approach to define the relationship between overgeneral memories and affect regulation.Even though the results does not fit perfect with previous research when considering the case of ‘가책’(GUILTY). Despite ‘가책’(GUILTY) was negative word, it doesn’t seem to be overgeneralized. We can interpret this as the guilty experience are not strong enough to regulate the affect of participants more than ‘죽음’(DEATH).We can overcome those weakpoints by increasing data and improving our early approach. Further research will be able to introduce other type of story grammar and find which story grammar is appropriate for representing autobiographical memory as story grammar format. Different formulation defining OGMpoint from story grammar could be suggested.

is too small, the value of OGMpoint will be huge, and then it will destroy the overall characteristics of OGMpoint. There has been no reference and previous research to deal with autobiographical memory as story grammar format. A contribution of this research is the first approach to formulate the overgeneral memory using combination of autobiographical memory with story grammar. If the methods are modified and improved through additional research, it will be powerful approach to define the relationship between overgeneral memories and affect regulation.Even though the results does not fit perfect with previous research when considering the case of ‘가책’(GUILTY). Despite ‘가책’(GUILTY) was negative word, it doesn’t seem to be overgeneralized. We can interpret this as the guilty experience are not strong enough to regulate the affect of participants more than ‘죽음’(DEATH).We can overcome those weakpoints by increasing data and improving our early approach. Further research will be able to introduce other type of story grammar and find which story grammar is appropriate for representing autobiographical memory as story grammar format. Different formulation defining OGMpoint from story grammar could be suggested.  Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML