-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(2): 71-75

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.06

Sleep Quality and Mindfulness as Predictors of Depression, Anxiety and Stress

Alexis Postans 1, Aileen Pidgeon 2

1Faculty of Society & Design, Bond University, Australia

2Assistant Professor Psychology, Faculty of Society & Design, Bond University, Australia

Correspondence to: Alexis Postans , Faculty of Society & Design, Bond University, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Compared to the general population, university students experience higher rates of poor sleep quality and depression, anxiety, and stress. These issues impact upon students’ psychological wellbeing, academic studies, and everyday functioning. Mindfulness has been shown to influence depression, anxiety, and stress, as well as sleep quality. The aim of the current study was to examine whether mindfulness and sleep quality predicted depression, anxiety and stress in a sample of 173 Australian university students. Participants were recruited through an online research participation pool and were aged between 18 to 57 years, including 132 females and 34 males. Participants completed an online survey comprising a series of questionnaires that measured self-reported depression, anxiety, stress, sleep quality, and mindfulness. Results showed that sleep quality and mindfulness significantly predicted depression, anxiety, and stress. However mindfulness alone did not predict sleep quality. The findings indicated that students with poorer sleep quality reported higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, and students with higher levels of mindfulness reported lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. The present study provides preliminary support for universities to develop and implement programs to cultivate mindfulness in university students, and health promotion and educational programs that emphasise the importance of both sleep quality and psychological wellbeing in university students.

Keywords: Sleep quality, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Mindfulness

Cite this paper: Alexis Postans , Aileen Pidgeon , Sleep Quality and Mindfulness as Predictors of Depression, Anxiety and Stress, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 71-75. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.06.

Article Outline

1. Background / Objectives and Goals

- There is increasing concern about the mental health and wellbeing of university students in Australia. Research by Stallman (2010) found that 83.9% of students across two universities reported elevated levels of psychological distress compared to 29% of the general population. The term “psychological distress” is used in the literature to collectively describe the three related but distinct negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Depression, anxiety, and stress can lead to a number of negative outcomes for university students, including lower academic performance, failure to complete academic studies, substance abuse, and burnout (Dyrbye, Thomas, & Shanafelt, 2006). Furthermore, research suggests that burnout seems to be associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent suicidal ideation (Dyrbye et al., 2008). Disability, as measured by a reduced capacity for work or study activities, has also been shown to increase significantly with higher levels of psychological distress (Stallman, 2010).Another issue facing university students is poor sleep quality, which can be measured across several domains including sleep disturbance and insomnia (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). Poor sleep quality has been linked to number of negative outcomes among university students, including attention problems (Pagel, Forister, & Kwiatkowki, 2007), lower academic performance (Gaultney, 2010), driving while drowsy (Cummings, Koepsell, Moffat, & Rivara, 2001), risk taking behaviour (such as violence and substance use; O’Brien & Mindell, 2005), impaired social relationships (Carney, Edinger, Meyer, Lindman, & Istre, 2006), and poor health (Smaldone, Honig, & Byrne, 2007). Although sleep quality and depression, anxiety, and stress may individually affect university students, evidence suggests that these problems are related. Poor sleep quality is considered both a predictive sign and symptom of many illnesses, and studies have shown that university students are twice as likely to experience poor sleep quality compared to the general population (Cheng et al., 2012; Buboltz, Brown, & Soper, 2001). However to date, a paucity of research has been conducted on whether sleep quality predicts depression, anxiety, and stress among university students. The present study sought to address this gap in the literature. Contemporary research suggests that mindfulness may influence depression, anxiety, and stress. Mindfulness may be conceptualised as “the state of being attentive to and aware of what is taking place in the present” (Brown & Ryan, 2003, p. 822), while refraining from the normal tendency to categorise experiences as either positive or negative. These elements of mindfulness, namely awareness and acceptance, as regarded as potentially effective antidotes to depression, anxiety, and stress (Keng, Smoski, & Robins, 2011). Coffey and Hartman (2008) identify three mechanisms through which mindfulness is thought to act: emotion regulation, reducing rumination, and nonattachment. Numerous studies have demonstrated a negative relationship between mindfulness and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress among university student samples (Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004; Brown & Ryan, 2003; Coffey & Hartman, 2008). However scarce research has examined whether mindfulness predicts depression, anxiety, and stress among university students. The present study sought to address this research question. Mindfulness has also been shown to influence sleep quality (Howell, Digdon, Buro, & Sheptycki, 2008). A conceptual framework proposed by Ong, Ulmer and Manber (2012) details the mechanisms of metacognition in the context of insomnia treatments. This model proposes that increasing awareness of the mental and physical states that are present when experiencing insomnia symptoms, and then learning how to shift these mental processes, can promote an adaptive stance to an individual’s response to these symptoms. These metacognitive processes are based on balanced appraisals, cognitive flexibility, calmness, and re-commitment to values, and are thought to reduce sleep-related arousal, leading to remission from insomnia. Ong et al’s. (2014) research provides empirical support for this model. Ong et al’s study evaluated the efficacy of mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic insomnia. The findings revealed that meditation-based treatments were effective in reducing total wake time in bed and sleep-related arousal, along with clinically significant changes in treatment response and remission. These results on pre-sleep arousal provide support for the efficacy of mindfulness meditation in reducing psychophysiological arousal, which is commonly found among sufferers of chronic insomnia disorders. It remains unclear, however, whether individuals with high levels of mindfulness experience greater sleep quality, even outside the context of structured meditation-based treatments. The current study sought to address this research problem. The Present StudyThe current study was designed to address a gap in the literature on the relationship between mindfulness, sleep quality, depression, anxiety, and stress in Australian university students. Data was obtained using survey methodology. The aim of the current study was to determine whether sleep quality and mindfulness predicted depression, anxiety, and stress. A second aim was to determine whether mindfulness predicted sleep quality. It was hypothesised that:1. Sleep quality and mindfulness would significantly predict depression, such that poorer sleep quality would result in higher levels of depression, and greater levels of mindfulness would result in lower levels of depression. 2. Sleep quality and mindfulness would significantly predict anxiety, such that poorer sleep quality would result in higher levels of anxiety, and greater levels of mindfulness would result in lower levels of anxiety. 3. Sleep quality and mindfulness would significantly predict stress, such that poorer sleep quality would result in higher levels of stress, and greater levels of mindfulness would result in lower levels of stress. 4. Mindfulness would significantly predict sleep quality, such that greater levels of mindfulness would result in better sleep quality.

2. Method

- Participants The sample consisted of 173 Australian university students aged between 18-57 years (M = 24.45, SD = 7.72) including 132 females (76.3%) and 34 males (19.7%). MaterialsThe online survey consisted of a series of self-report questionnaires to collect data on demographics, psychological distress (depression, anxiety, and stress), sleep quality, and mindfulness. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale – 21 Items (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995).) is a 21-item self-report measure of depression, anxiety, and stress. The depression subscale measures dysphoric mood, including inertia and hopelessness. The anxiety subscale measures symptoms of fear, panic and physical arousal. The stress subscale measures symptoms such as irritability and tension. The DASS-21 has strong psychometric properties. Studies have reported high internal consistency reliability for the subscale scores in both clinical and nonclinical samples, with alpha coefficients ranging from α = .82 to. 97 (Henry & Crawford, 2005; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989) is a 19-item self-report measure of sleep quality within a one-month timeframe. The 19 items are categorised into seven components, which include sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The scores for each component are combined to yield a global score, ranging from 0 to 21, where higher scores indicate poorer sleep quality. A global score of five or above indicates overall poor sleep quality. The psychometric properties of the PSQI have been validated with a number of studies reporting high validity and reliability (Beck, Schwartz, Towsley, Dudley, & Barsevick, 2004).The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory – 14 Items (FMI-14; Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmuller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006) is a 14-item shortened version of the original scale used to measure mindfulness. The FMI is most suitable for use in generalised contexts, where knowledge of the Buddhist teachings on mindfulness is not assumed. Higher scores indicate greater levels of mindfulness. The purpose of the FMI-14 is to characterise peoples’ subjective experience of mindfulness within a certain timeframe, which in the present study was the past month. The FMI-14 has been demonstrated to possess good psychometric qualities, with the overall reliability coefficient of α = .88 indicating a high degree of internal consistency.

3. Results Main Analyses

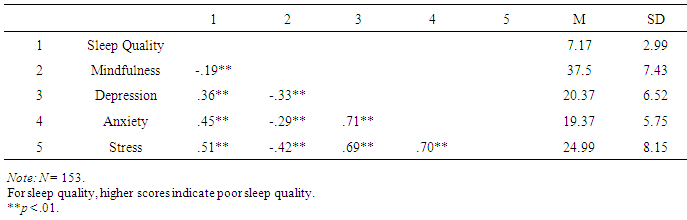

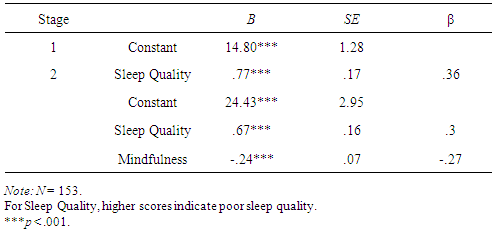

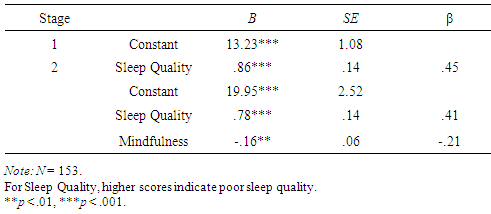

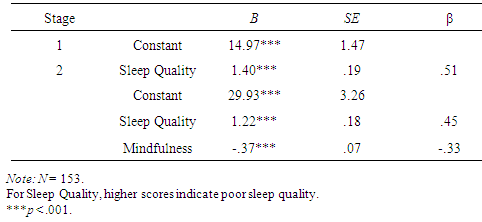

- Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether sleep quality and mindfulness predicted depression, anxiety, and stress. Three hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted in total. Sleep quality was entered at step one of the model, and mindfulness was entered at step two of the model. Results were interpreted at an alpha level of .05.Table 1 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients, mean scores, and standard deviations for the predictor and criterion variables. The mean score for sleep quality indicated that participants had poor sleep quality, as indicated by scores of five or above on the PSQI (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). Specific cut-off scores and population norms are not available for the FMI-14, however the mean and standard deviation scores for three samples obtained by the authors of the scale can be used as a frame of reference (sample from the general population with no meditation experience, M = 37.24, SD = 5.63, n = 74; sample from the general population with varied mediation experience, M = 34.52, SD = 6.77, n = 246; clinical sample, M = 31.17, SD = 7.18, n = 103; Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmuller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006). Therefore the mean score for mindfulness in the present study was close to that found in the sample from the general population with no meditation experience.

|

|

|

|

4. Acknowledgments and Legal Responsibility

- I hereby certify that this paper represents original work unless otherwise cited, and that this work is previously unpublished.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML