-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(2): 63-70

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.05

Parental Support as Perceived by Taiwanese University Students during Career Development

Ching-Hua Mao 1, Ying-Chu Hsu 2, Tzu-Wei Fang 2

1Center for General Education, Chihlee University of Technology, Taiwan

2Institute of Education, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan

Correspondence to: Ching-Hua Mao , Center for General Education, Chihlee University of Technology, Taiwan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

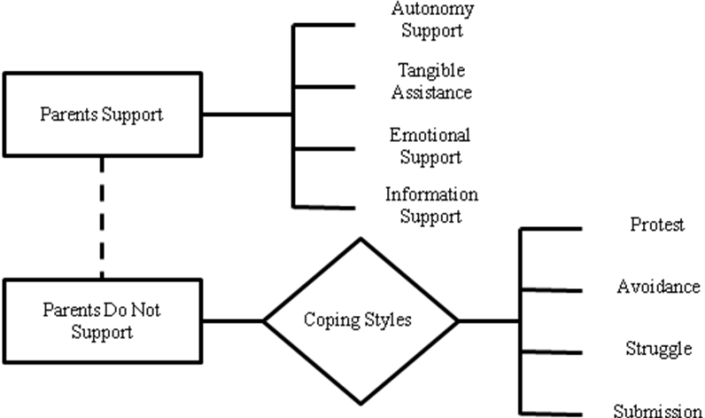

This study explores Taiwanese university student perceptions of parental support within a Chinese family context. The study used the phenomenological approach and conducted focus group interviews with 17 university students. The results were analyzed using thematic analysis. The main conclusions of this study were as follows: (1) Parental support includes four themes “autonomy support,” “tangible assistance,” “emotional support,” and “information support.” (2) Autonomy support is a significant theme of parental support, however, it is also the most difficult for Taiwanese parents to provide. (3) When there is conflict between the interest development of university students and parental expectations, students use four different coping styles: protest, avoidance, struggle, and submission.

Keywords: Parental support, Taiwanese university student, Autonomy support, Chinese culture, Filial piety

Cite this paper: Ching-Hua Mao , Ying-Chu Hsu , Tzu-Wei Fang , Parental Support as Perceived by Taiwanese University Students during Career Development, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 63-70. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The relational approach to career development has been of emerging interest in recent years. This approach focuses on the connection between a person’s quality of interactional relationships and career development. The relational approach to career development also assumes that significant others are a resource that seriously affects the process of career exploration and career decision-making (Blustein, 2011; Schultheiss, 2003). Furthermore, postmodern social constructionism emphasizes the influence of contextual factors on the individual, which greatly affects the relational approach to career development (Blustein, Schultheiss, & Flum, 2004) and combines the structure of context with career development. Research confirms that parental support is the most important interactive context element that influences career development (Fisher & Griggs, 1995; Nauta & Kokaly, 2001; Schultheiss, Kress, Manzi, & Glasscock, 2001).Chinese society is a collectivist society that values relationships with other people; therefore, the study of support relationships and career development is valuable (Blustein, 2011; Schultheiss, 2003). Research by Tang, Fouad, and Smith (1999) on predictive factors that influence Asian-American university students when making career decisions found that the family involvement variable within immigrant families directly affects career choices. The personal interests of these Asian-American university students had no significant correlation with their career choices, whereas other American university students’ interests were directly correlated with their career choices (Lent et al., 2001). The difference between Western families and Chinese families regarding the effect of parental roles on children’s career choices prompts investigation.Based on the research mentioned above, this study explores university student perceptions of parental support within a Chinese family context to provide reference for future research and to guide practitioners in related areas.

1.1. Social Cognitive Career Theory and the Relational Approach to Career Outlook

- Of the career theories, two schools of thought emphasize the influence of the environmental context of an individual on career development. Social cognitive career theory (SCCT), developed by Lent, Brown, and Hackett (1994), states that “background contextual affordance” and “contextual influences proximal to choice behavior” each influences the development of self-efficacy and career choices of an individual. The other theory is derived from the relational approach to career development, which stresses the significance of relationships on human development and focuses on the positive effects of relationship experiences in situational contexts on the career development of a person. Lent et al. (2001) emphasized the significance of contextual factors in the SCCT model. They observed that contextual support directly impacts on self-efficacy, thus indirectly affecting expected outcomes, interests, and career choices. Lent et al. also noted that within contextual factors, each contextual support and impediment variable has a different degree of influence on an individual. For instance, gender, ethnicity, culture, and social groups, all have unique contextual factors. Therefore, different forms of parental support in the family context may reflect the individualism of the West and the collectivism of the East.

1.2. Parental Support and Related Studies

- Many qualitative studies have explored this field of study. Schultheiss et al. (2001) conducted personal interviews to understand the roles of relationships between respondents and their parents, siblings, and other important people during the process of respondent career development, and the correlation of these relationships with career exploration and decisions. Schultheiss et al. concluded that relationships are a multi-dimensional source of support; the dimensions of support include emotional support, social integration (that is, network support), esteem support, information support, tangible assistance, role in difficult career decisions, role model influences, and emphasized financial aspects of choices. Blustein et al. (2001) qualitatively analyzed the intersection of work and inter-personal relationships and identified relationship-related topics from published research cases. They indicated that relationship support is a distinct category which includes emotional and tangible assistance. Tangible assistance is further divided into information and financial support. The participants in a study by Phillips, Christopher-Sisk, and Gravino (2001) were workers who had entered the workplace after graduating from high-school. The types of relationships that influenced their career decision-making included emotional and information support (the terminology used in the study was unconditional support, information provided, and alternatives provided). All of the studies described agree that relationship support is multi-dimensional, but in these studies, parents were not the focus of support-providers and study respondents all had Western backgrounds. Therefore, support dimensions in a Chinese cultural context where relationships and family connections are highly valued are worth investigating.

1.3. The Effects of Eastern Filial Piety on Career Development

- Eastern culture is generally collectivist. Markus and Kitayama (1991) state that the self that is shaped by Eastern culture is an interdependent one. Thus, the issue of relationships cannot be disassociated from making career decisions in Chinese or Asian culture (Young, Ball, Valach, Turkel, & Wong, 2003). In particular, Chinese society is ingrained with Confucianism, which prioritizes filial piety and thus encourages adolescents to meet parental expectations and comply with parental wishes (Leung, Hou, Gati, & Li, 2011). Therefore, family responsibilities and parental expectations are highly valued. This is different from Western culture which emphasizes individual ability to make career decisions independent of outside influences and also encourages the individual to advance toward personal goals and dreams.In exploring the traditional Chinese culture of filial piety, Yang, Yeh, and Huang (1989) extracted the following four factors using factor analysis: respecting and loving parents, supporting and memorializing parents, oppressing oneself, and glorifying parents. Yeh and Bedford (2003) combined the first two factors as “reciprocal filial piety,” and the latter two factors were combined as “authoritarian filial piety.” Authoritarian filial piety is associated with suppressing the self to conform to parental expectations and working hard to establish a career that glorifies parents.The core of Chinese culture has changed tremendously because of the cultural exchange between East and West in modern times. The nature, role, and importance of filial piety are also transforming. Research by Leung et al. (2011) found that in mainland China, where Westernization is more recent, parental expectations as perceived by university students predicts the difficulty of making a career choice. Conversely, in Hong Kong, where Westernization is older, parental expectations perceived by university students could not predict the difficulty of making a career choice. Because in Taiwan, mainland China, and Hong Kong, Chinese culture has been Westernized to varying degrees, levels of traditional and modern cultural exchange in these regions are likely to be different. What filial piety mean to young people in these different regions may also be different. The degree of Westernization in Taiwan is somewhere between mainland China and Hong Kong and there is a lack of indigenous research on the study of Chinese culture and career development. Consequently, the relationship between cultural context and its influence on young people’s careers in Taiwan is an issue worthy of study.In conclusion, the trend in career research is to attempt to understand the effect of contextual factors on career development. However, Taiwanese studies in this area are rare. A more in-depth understanding using a qualitative approach is required to understand the inter-related influences of Chinese culture and how youth career developments intersect and influence each other. This study focuses on parental support perceived by university students in Taiwan within a Chinese family context.

2. Method

2.1. Research Approach and Design

- This study uses a phenomenological, qualitative approach to understand the essence of parental support as perceived by young people in Taiwan within the context of Chinese culture. The phenomenological perspective focuses on the description of the life of the participants and examines their psychological essence (Giorgi, 1997). To achieve this, the researchers adopted open attitudes devoid of their own preperceptions and listened to the inner voices of the participants regarding their lives.To collect data, this study mainly used the focus group interview method which creates stimulation from individual responses and group interactions, thereby encouraging members of the group to comment and respond. The purpose of using focus groups is to generate participant opinions rather than having them reach a consensus or assimilate opposing views (Heppner, Wampold, & Kivlighan, 2008). This will provide the study with a variety of information. To understand whether the interview design would be relevant to the research topic, a pilot study was conducted on two students (one male and one female whose interview codes were P and Q) by interviewing them individually. These results were used as a reference for revising the interview outline.

2.2. Research Participants

- 2.2.1. Participants. A purposive sampling approach was used and 17 male and female students were invited to participate through several university (and college) counseling centers. Except for the two students who were interviewed in the pilot study, all other 15 students participated in the first and second focus-group meetings. Participants were invited based on the following principles: (1) gender balance; (2) participants from diversified departments must be included to prevent a concentration of students in a particular field of study; (3) participants in different years of study at university must be included. Based on these criteria, 8 male and 9 female students in Arts (4 students), Business (5 students), Medicine (4 students), Engineering (3 students) and Education (1 student) were recruited. There were 4 freshman, 6 sophomore, 5 junior, and 2 senior year students. Generally, the invited participants complied with the gender, field of study, and year of study criteria. 2.2.2. Researcher and co-researchers. The first author of this study has been a university career-planning instructor for approximately 11 years, has practical career counseling experience, and has been involved with career-related studies. The first author was the main focus group interviewer and the data analyst. The second and third authors are full-time graduate school counseling program instructors, both with practical experience in the area of career counseling. The second author’s Master and PhD theses were career-related, and she has had several years of teaching experience in career counseling. The second and third authors assisted with analyzing and verifying the research data.

2.3. The Collection, Organization, and Analysis of Data

- 2.3.1. Collection and organization of data. The focus group interview outline that was used twice in this study was revised from the pilot study results, where two individual interviews were first conducted. The focus group interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview method centering on the issues of parental support and career development while allowing participants to share their personal experiences. Individual interview and focus group interview participants gave consent for the interviews to be recorded. These recordings were then made into transcripts.2.3.2. Data analysis. Data were analyzed according to Braun and Clarke’s Thematic Analysis (2006). This section describes the analytical process steps which were followed. (1) Being familiar with the data: write out transcripts, re-read interview information, and write down any initial understanding of the data. (2) Generating initial codes: encode meaningful data on the transcripts and categorize the coded interview lines. (3) Searching for themes: organize the codes generated in Step 2 to discover proto-themes and list the codes within these proto-themes. After this step, the proto-themes of this study were identified as responses to whether parents support career decisions. (4) Reviewing themes: examine whether the proto-themes relate to the codes and transcripts, and make a theme analysis chart. Figure 1 shows the final version of the theme analysis chart. (5) Defining and naming themes: edit and name the proto-themes according to analyzed data and define each named theme. After clarifying and defining the themes, two categories and eight themes were classified. These are: autonomy support, tangible assistance, emotional support, information support, protest, avoidance, struggle, and submission. (6) Producing the report: review whether the data selected answer the intended research questions and then write the research analysis report.

3. Results

- Figure 1 shows that the study results are grouped into two categories – “parents support” and “parents do not support” – and eight themes.

| Figure 1. Thematic Map |

3.1. “Parents Support” Theme Analysis

- The study found that there are four themes in the “parents support” category: autonomy support, tangible assistance, emotional support, and information support.3.1.1. Autonomy support.Parents respect the child’s autonomy. Some participants were grateful that their parents respected their opinions and allowed them do what they desired. For example, when participant Q was selecting a major for university, he was faced with the problem of choosing a major that did not match his mother’s expectations, but his father let him know that, “If this is really what you want, then [we will] respect your wishes” (Q007). Q also said that his father “would not say should or shouldn’t because I’m the one who will be studying it, not him; he thinks it’s more important that I like it because I didn’t take the test for him to study college” (Q007).C is very independent and opinionated; after thinking things through carefully, he does what he wants. When C insisted on making his own career decisions, he still cared about his parents support. C said that, in particular, his mother’s support allowed him to pursue his own career: “A reason I can be like this is because of my mother’s support. Yeah, it would be much more difficult if my parents did not approve” (C024).Mutual respect in father-son relationships. Two male participants in this study reported that their fathers gave them the independence to make career decisions, but also warned them of the responsibilities they must accept when making their own decisions. Participant O’s father said, “When you are making a decision, you must think three years ahead, and if you think you won’t regret making this decision then, you can go ahead with it” (O011). There seemed to be a mutual respect between the father and son when the father encouraged the son to pursue his desires, and the son respected the father’s teachings. 3.1.2. Tangible assistance.Financial support. Participant A is currently studying in the Department of Health Care Management at a private university. When A was selecting a university, she struggled between choosing a major that was offered at a private university with higher tuition and choosing a public university with lower tuition that did not have a major she was interested in. A’s father told her, “It doesn’t matter which major you select, as long as you make the right choice and do not regret it, then I will support you financially” (A103). Action support. Parents help when they know their child is in need of assistance. For example, when participant E wanted to apply for the Department of Motion Pictures, both parents were against it. “Mother … lets me follow my dreams, but of course she still hopes that I can have a stable job in the future so I can make a living …. But she still goes to the exam with me and pays for my application fees. She still supports me, but she will continuously and secretly try to persuade me to do otherwise” (E006).Offer advice and guidance. In the midst of confusion and having to make decisions, children anticipate advice and guidance from their parents. When participant K was considering whether he could take on the role of an executive in a student club, his father gave him advice. “He gave me something to refer to, like a general direction, like I can use it as reference” (K029). Participant M also mentioned that her mother offers advice. “You hope that someone can give you some advice” (M028). Both students also stressed that parental advice was only given to help them make a decision. “I still make the final decision” (K029). “I wouldn’t especially do as she says” (M027). Thus parental consultation is selectively accepted by children, and they also insist on making their own career decisions.Mother as mediator in parent-child conflict. Parents and children have different opinions regarding career plans. Interestingly, when the father is not supportive of the child’s plans, the mother often acts as a mediator to facilitate communication between father and child. Participant J’s plans for the future were vastly different from her father’s plans for her. “Mother hopes I can do the best I can in whatever I want to do, so that I can prove to him that this was the right choice …. She will also try to say that Father’s plans are good, too. The point is, she will try to coordinate both sides!” (J005). Assistance provided when encountering frustrations. When children face frustration and parents immediately help them, the children are grateful and it leaves a lasting impression on them. For example, when N took the Basic Competence Test for junior high school students (the entrance exam for senior high school) and did poorly, his father – an English teacher – helped him make an English practice book composed of mistakes he had made in previous English tests. His father asked him to write in it every day. When N took the exam a second time his grades were greatly improved.Among the sub-topics that provided substantial support, university students need financial support from their parents. The career goals of young students who cannot support themselves financially frequently require substantial sponsorship from their parents. Moreover, when participants face problems during career decision-making, they anticipate that their parents will offer advice and guidance. However, young adults with strong self-awareness only use parental advice and suggestions as references; when they actually make decisions they are inclined to follow their own will.Additionally, the mothers of some of the participants cannot bear their children’s feelings of “loneliness”; these mothers frequently play the role of coordinators and persuade their husbands to support children’s choices and set aside their own mainstream values. Alternatively, these mothers play the role of supporters and support their children financially to help them do what they choose. 3.1.3. Emotional support.Moral support for times of disappointment and frustration. When university students encounter setbacks and disappointment, they are most grateful for parental moral support. Participant E’s father had always been strict with her; however, when he discovered that her grades for anatomy and anatomy lab finals were low and that it was possible that she could fail the course, he told her, “It’s ok, just do your best” (E009). These words of encouragement gave her the emotional support and strength she needed to work harder. After listening to what participant E shared, participant O had the same feeling and emphasized that his parents are his reinforcement: “when you’re in trouble or when you’ve gone down the wrong path, your rescue unit can give you immediate support” (O046).Proposition that mothers understand their children better. Compared to fathers, some mothers seem to have more interaction with their children. This may be because they are often homemakers or stay-at-home moms, and therefore are able to have discussions with children about their futures and careers. As participant C explained, “In terms of support, Mother is more supportive; usually I spend more time with Mother” (C012). Spending more time with their children allows mothers to better understand them. 3.1.4. Information support.Parents actively assist with collecting information. There is a large selection of departments and majors to choose from at university, and often parents do not know the exact nature of these departments and majors. When their children express an area of interest, parents want to learn more about the field and anything related to it. When participant C mentioned that his mother uses an educational radio program to do this, participant A echoed that: “My mother would listen to the radio program while cleaning the house … and slowly collect this information, and then she would pass on the information to me and also help me analyze it” (A011).Collecting information by networking. When making a career decision, information is often a significant decision-making factor. When making such decisions, parents obtain information by using their personal networks to assist their children. For instance, participant I has a father who has a background in science and engineering. Participant I, who is also in an engineering program, said: “My father knows some people, so he can tell me some information that perhaps most people do not know” (I012).When respondents were selecting majors for university, most of them were confused and needed assistance. Parents then used their networks or other resources to obtain relevant information for their children. In this case, parental support is assertive and ample.

3.2. When Parents Do Not Support: Effects on Career Development and Children’s Coping Styles

- This study aims to explore parental support, but some participants also mentioned the coping styles they use when their parents do not support them. In particular, it is less likely for Taiwanese parents to give their children autonomy support than tangible assistance, information support, and emotional support. These parents often hold mainstream values that conflict with their children’s interests, and when children insist on following their own interests, discrepancies between the child’s and parental expectations result.3.2.1. Protest. Some participants’ parents have certain career expectations of their children and some even interfere with their choices. For example, participant J’s family members are all civil servants, so her father strongly desired that she take civil-servant-related exams. When J did not comply, “Father secretly applied to the exam for the police academy … he secretly applied for me and told me to take the exam. I purposely handed in an empty exam paper. The application fee wasn’t cheap. Of course I went to a different school in the end” (J007). 3.2.2. Avoidance. When university students realize that their parents’ expectations of them are so different from their own goals that there is difficulty communicating, they avoid discussing it with their parents altogether and proceed alone to what they want to do. Participant K’s mother has high expectations of her children. She expects them to get into the best schools and study popular courses such as medicine or computer programming. K said, “When I hear this, I will automatically ignore it” (K003). 3.2.3. Struggle. Female participant M has a good relationship with her mother. M’s mother showed concern and participated in M’s career decision-making process; offering advice and information. Although M’s mother respects her choices, because of their close relationship, M cares immensely what her mother thinks. Thus, M faces the problem of whether to make her own decisions or adhere to her mother’s expectations. For example, M studied in a special music program when she was in elementary school, but she wanted to transfer to normal classes after entering junior high school. “Mother respected it, but at the same time found it very unfortunate that I gave up the music class, so it made me hesitant” (M015). This wavering between self-autonomy and her mother’s expectations followed her to high school when choosing subjects and to university when selecting majors. “Maybe I’m just not sure whether I have the capability to do it, and it doesn’t seem like such an important decision to make, so I was very casual and laidback about it. In the end I chose to major in computer science” (M015).3.2.4. Submission. B, another female participant, did not want to go against her father’s wishes and yielded to his expectations. “Ever since junior high school, my father would tell me what is best and what to do. Father wished for me to take the civil service exam, and in the beginning I just didn’t want to disappoint him” (B023). This seems to illustrate the traditional notion of filial piety in the Chinese culture, where children submit to parental wishes and do not go against them. However, B said, “I’ve never known what I was interested in, and when father wanted me to do something, I felt like perhaps I could give that a try. Also I don’t want to disappoint my parents, so I feel that my future is based on my parents’ expectations” (B023). Therefore, for B who cares immensely about parental expectations, the opportunity to explore her interests seems lost.

4. Discussion

4.1. Wavering between Career Interests and Parental Expectations

- As many as 15 of the 17 study participants emphasized the importance of having autonomy over their own careers. Therefore, parental respect and autonomy-support was a significant theme of parental support in this study. Furthermore, compared to young adults in the West who are encouraged to pursue their own career goals in an independent and individualistic culture, participants in this study persist in career decision-making and anticipate parental approval and support because of the Chinese collectivist culture.Fouad et al. (2008) reported that when some Asian-American participants reached adulthood and made career decisions, or even if they had already established their careers, they nonetheless hoped for their parents to show support. Wang (2002) studied recent university graduates in Taiwan and found that “personal interests/individual characteristics” and “expectations of others/social values” were two major references for the formation and selection of career goals. According to their differences, Wang identified three orientations: “other-oriented,” “self-oriented,” and “in-between.” Participants categorized in the “in-between” group were the most career-oriented, had the clearest career goals, and were the most ambitious career-wise. Therefore, in a collectivist culture, Chinese young adults who do not receive support for autonomy over their careers are worse off than those in the “in-between” group. Therefore, negotiating and communicating maturely and rationally with parents (other/social values) about career interests is vital because appropriate communication skills may garner parental support. We predict that communication skills may be a mediating variable in the correlation between parental expectation and career development. When children face conflict between career interests and parental expectations, if they communicate with their parents in a mature and appropriate manner, they may have positive career development. Further studies should confirm this hypothesis, especially in a collectivist Chinese culture.

4.2. Blending of Filial Piety Culture and Career Development

- In a collectivist Chinese culture, family is more important than the individual, therefore this culture values an individual’s family responsibilities and obligations (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999). This is also reflected in the traditional value of glorifying parents (or family) and encouraging young adults to achieve career success to honor parents and provide them with a comfortable life. In this study, one female participant mentioned that a source of motivation is making her parents proud and being able to offer them a good life when she achieves success. Filial piety may be a source of motivation (Fuligni et al., 1999); but obeying parental expectations may also impede the development of an individual’s career interests. One female participant said that because she had followed her father’s advice throughout her career, she had lost the opportunity to explore her own career interests. Therefore, it is not clear whether the influence of traditional filial piety is beneficial or harmful to a young adult’s career development.The “dual filial piety model” proposed by Yeh and Bedford (2003) can resolve this question. As explained in the literature review, the dual filial piety model divides filial piety into “authoritarian filial piety” and “reciprocal filial piety.” “Authoritarian filial piety” is absolute obedience to the parents and the distinct rank between parent and child; therefore it suppresses the development of the child’s independence and autonomy. However, this study indicates that the university students interviewed are no longer restrained by the traditional culture of filial piety and had courage to pursue their own dreams. This reflects the gradual diminishment of “authoritarian filial piety” in Taiwanese society under the influence of Western values. “Reciprocal filial piety” is still prevalent in Chinese society (Yeh & Bedford, 2003), where ancestors and parents are respected and honored.Some studies observed a positive relationship between filial piety and family cohesion and unity, and parent-child harmony (Cheung, Lee, & Chan, 1994; Roberts & Bengtson, 1990), and that with filial piety, there is less parent-child conflict (Yeh & Bedford, 2004). In fact, with a relational approach to career development, the individual’s interpersonal relationships are interconnected with career development. Therefore, the interaction with family and harmonious parent-child relationships generated by “reciprocal filial piety” should be beneficial to the child’s career development. From this point of view, the relational approach to career development can be connected with “reciprocal filial piety”; however, this hypothesis is inferred by us and was not presented in the related literature, thus, future research should confirm it.

5. Limitations

- Compared to Western literature on relational support, participants of this study highlight autonomy-support, which is not the same as “esteem-support” which is an important Western value (Schultheiss et al., 2001; Schultheiss et al., 2002). Autonomy-support does not include having faith in a person’s capability and strengthening his/her self-esteem. This demonstrates the conservative and humble nature of Chinese culture in Taiwan, where parents are not accustomed to praising or validating their children. However, Taiwanese parents may show their validation in other ways that can be felt by their children. Furthermore, because this study uses a focus group interview method, participants are in a group-sharing environment where most people do not know each other. Because of the humble nature of Chinese culture, it is difficult for participants to express their parents’ approval of them, which may be a limitation of this study. To fully understand how parents in a Chinese cultural context exhibit their affirmation and trust in their children, future research should use in-depth interviews to eliminate participant reluctance to describe their positive qualities.In addition to this limitation of how parents express validation for their children, the differences between how Eastern and Western cultures value esteem may also be reflected in this study. Studies on participants from Western culture, which values self-esteem, found that without exception, the means or medians of self-esteem items were higher than the midpoints (Baumeister, Tice, & Hutton, 1989). However, Heine, Lehman, Markus, and Kitayama (1999) showed that Eastern participant self-esteem scores were not especially high, but closer to the median. Therefore, there is a significant difference in self-evaluation of self-esteem between the individualistic West and the collectivist East. Although studies have demonstrated self-esteem differences between Eastern and Western cultures, the effect of these differences on career development is yet to be explored. In particular, Schultheiss et al. (2002) believe that esteem support can increase an individual’s self-esteem and self-efficacy, thereby giving them courage to explore career interests and make career decisions. Therefore, esteem support is an important topic for career research and further understanding of the development and characteristics of esteem support will be useful in analyzing future career self-efficacy, career exploration, and career decisions in Chinese culture.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML