-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(2): 53-57

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.03

University Rugby Sevens Players Anxiety and Confident Scores between First Game and Second Game Based on Different Position of Play

1Faculty of Sports Science and Recreation, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

2Faculty of Business and Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Selangor, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Mazlan Ismail, Faculty of Sports Science and Recreation, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This pilot study determined the pre-competitive anxiety and confident scores of the university rugby sevens players based on different position of play between first and second games. The participants consists of 12 players from Griffin Rugby Club known as UiTM N9 aged 18 to 22 years (M= 19.50, SD= 1.62) with 4 to 10 years playing experiences (M= 5.92, SD= 1.83), with different positions (6 forwards; 6 backs). The participants completed the CSAI-2R questionnaire prior to the games. The results showed that there were no significant difference in pre-competitive anxieties of the players in the forwards and backs positions. However, the players had a higher in cognitive anxiety and somatic anxiety before the first game compared to the second game and no significant difference in self-confidence scores. It is probable the cognitive anxiety and somatic anxiety were perceived as something with slightly negative influence on their first game. Coaches need to consider the psychological skills training in order to control and modify the anxiety states of the players before competition.

Keywords: Cognitive anxiety, Somatic anxiety, Self-confidence, Position of play

Cite this paper: Mazlan Ismail, Afizan Amer, University Rugby Sevens Players Anxiety and Confident Scores between First Game and Second Game Based on Different Position of Play, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 53-57. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In sports situation, anxiety is considered the most common component that influences sports performance [1]. In general, anxiety is a negative emotional state where a person experiences a mixture of worry, nervousness and fear [2]. Anxiety is a state of tension, worry, expectance of some dreadful event. A person who is anxious is unaware of the cause of uncomfortable state and tension. This is why anxiety is accompanied by symptoms such as voluntary muscles overload, higher activity of the autonomic nervous system, intensified manifestation of certain organs or certain body systems [2]. Considerable attention has been received on the effect of competitive anxiety upon performance. Often it is assumed that either beneficial or detrimental effect is caused by anxiety during competition that is, a negative emotional state characterized by feelings of nervousness, worry, apprehension and bodily arousal [3]. Anxiety is multidimensional where the state and trait of anxieties are in nature with the somatic and cognitive components [4]. In sports, cognitive anxiety is the mental aspect of anxiety. For instance, it is when a person worries in high intensity resulting in negative thoughts which may comprise in losing self-esteem, fear of failure, and no self-confidence. In fact it could result to poor performance by the athlete in competition [4]. It may start prior to the competition in the form of pre-competitive anxiety thus affecting performance throughout the competition. Somatic anxiety on the other hand is the physical component of anxiety. For instance, it refers to a person who perceives physiology changes, which includes an increase of heartbeat, muscle tension, breathing difficulty, and sweating. However, the perceived physiological changes associated with somatic anxiety may be genuine or merely an anxious person’s perception of a change that is nonexistent. Pre-competitive state anxiety is defined as an anxiety that occurs prior to an actual competition [5]. Never has there been an athlete who did not feel anxious during their career. Even famous players, with a high world sports rank have admitted in front of a big audience that they feel nervous few days before the competition. It is probable factors of fear of performance failure to their true potential during competitions. Fear of physical injury is another great concern for athletes are afraid during competitions. The fear can contribute to pre-competitive state anxiety, and leads to poor performance. Additionally, situational ambiguity likes athletes’ trains hard to compete, and their motivation is maintained by their involvement in competitions. Any doubts about their selections for competition or being allowed to play in their favourite positions in a team can cause pre-competitive state anxiety in an athlete before competition. Finally disruption of well learned routine for example athletes perform well when they know and understand what they are doing and also what is expected of them. As a result, pre competitive state anxiety occurs when an athlete is told to change his or her style of play or play in an unfamiliar position without practice or prior notification. Pre- completion anxiety reaches its peak or highest level just before the start of competition creating anxiety in an athlete, and decreases once the competition starts. It is noted that anxiety is more prone on some athletes than others. For instance university athletes are more prone to anxiety compared to professional athletes which hinder their capability to perform in competition [6]. Previous study has investigated the symptom responses associated with competitive anxiety among team sports players (i.e., rugby, soccer, and hockey) [7]. The study incorporates dimensions of intensity, perceptions of direction, and frequency of intrusions from time to time changes. The results of change over time effects show that between 2 hours and 30 minutes prior to competition, intensities of cognitive and somatic anxiety increased and self-confidence decreased. Cognitive anxiety increased in frequencies from seven days to two days, one day to 2 hours to 30 minutes pre-competition. Meanwhile, frequencies of somatic anxiety increased from seven days to two days and 2 h to 30 min pre-event. Finally frequencies of self-confidence increased from seven to two days [7]. Recent qualitative study explored the potential of pre-competitive anxiety effects the performance of the rugby players [8]. There is significant reduction of pre-competitive anxiety after the twelve weeks training program. Additionally, if pre-competitive anxiety i.e., cognitive and somatic changes are to be used as an effective symptomatic marker for team sport performances [7], it is postulated that changes in pre-competitive anxiety would be accompanied by similar changes in the first and second games of the competition based on different position of play. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the pre-competitive anxiety of rugby sevens players between first and second games based on different position of play.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

- Data for the study was collected from 12 university rugby sevens players, aged 18 to 22 years (M = 19.50, SD = 1.62) with 4 to 10 years playing experiences (M = 5.92, SD = 1.83). Participants were measured from two different games (first and second) in a preliminary round from Griffin Rugby Club known as UiTM Negeri Sembilan. All players with different positions (6 forwards; props and hooker, 6 backs; half back, fly half, centre, and winger) were in International Sports Fiesta Competition 2014 at the time of data collection.

2.2. Materials and Procedure

- The Revised Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2R; Cox, Martens & Russell, 2003) was used to assess anxiety prior to the preliminary round. Additionally, state anxiety comprising cognitive (i.e., the mental element of anxiety) is referred to as expecting negative outlook to success and negative self-evaluations [9]. Meanwhile, somatic anxiety is the anxiety’s physiological and affective elements that grow directly from autonomic arousal such as rapid heart rate [10]. The CSAI-2R has a total of 17 items; 7 items in somatic anxiety subscale and 5 items in each subscale of cognitive anxiety and self-confidence. Some examples of somatic anxiety are “I feel jittery” and “My heart is racing”; Cognitive items include “I am concerned about losing” and “I am concerned about performing poorly”; Self-confidence items include “I feel self-confident” and “I am confident I can meet the challenge”. A 4-point Likert scale was used; not at all, somewhat, moderately, very much. Previous study found only cognitive anxiety showed an acceptable internal reliability with a Cronbach alpha coefficient which reported to be .83 [11]. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was .76 and was considered to be acceptable and preferable values [12]. Finally, descriptive statistic and paired – samples t-test and independent sample t-test were performed to determine pre-competitive anxieties between first game and second game and different positions of play of rugby sevens players.

3. Results

- To test the pre-competitive anxiety between first game and second game and different position of play, the paired sample t-test and independent samples t-test was used in this study. to tell whether there are significant differences in the mean scores on the dependent variable across the first game and second game and different position of play (i.e., forwards and backs). The preliminary assumption scores are reasonably normally distributed.

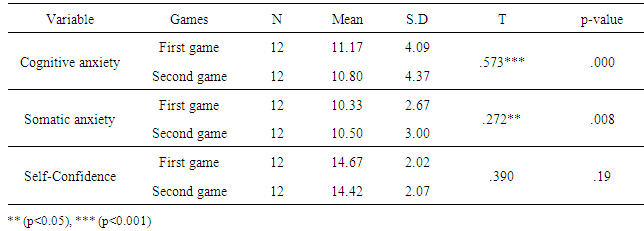

3.1. First Game and Second Game: Pre-competitive Anxiety

- A paired-sample t-test was conducted to evaluate the impact of the first game and second game rugby sevens players performance on cognitive anxiety (CSAI-2R). Table 1 shows that there was a statistically significant decrease in cognitive anxiety scores from first game (M=11.17, SD=4.09) to second game (M=10.83, SD=4.37), t (12) = .573, p < .001 (two-tailed). The mean decrease in Cognitive anxiety scores was 0.34 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from -.95 to 1.61. The eta squared statistics (.99) indicated a large effect size. Table 1 shows that there was a statistically significant decrease in somatic anxiety scores from first game (M=10.50, SD=3.00) to second game (M=10.33, SD=2.67), t (12) = .272, p < .05 (two-tailed). The mean decrease in somatic anxiety scores was 0.17 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from -1.18 to 1.51. The eta squared statistics (.01) indicated a small effect size. Additionally, there was no statistically significant different in confident scores from first game (M=14.67, SD=2.02) to second game (M=14.42, SD=2.07), t (12) = .390, p = .19 (two-tailed). The findings revealed that the states anxiety (i.e., cognitive anxiety and somatic anxiety) plays a slightly negative influence on their game preparation and opponent to play. The stressful condition may be caused by the external aspects such as physicality of opponents, huge number of spectators and intense feeling of responsibility from coaches. In other words athletes need to be ready earlier in each of the game in order to reduce their level of states anxiety [7].

|

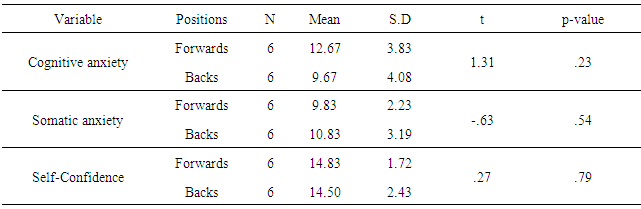

3.2. First Game: Pre-competitive Anxiety

- An independent – samples t-test that there was conducted to compare the first game cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety and self-confidence scores for forwards and backs. Table 2 shows that there was no significant difference in cognitive anxiety scores for forwards (M=12.67, SD=3.83) and backs (M=9.67, SD=4.08; t (12) = 1.31, p=.22, two-tailed). The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference = .30, 95% CI: -2.09 to 8.09) was very small (eta squared = .01). There was also no significant difference in somatic anxiety scores for forwards (M=9.83, SD=2.23) and backs (M=10.83, SD=3.19; t (12) =-.63, p=.54, two-tailed). The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference = 1.0, 95% CI: -4.54 to 2.54) was very large (eta squared = .9). Lastly, there was no significant difference in self-confidence scores for forwards (M=14.83, SD=1.72) and backs (M=14.50, SD=2.43; t (12) = -.27, p=.79, two-tailed). The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference = .33, 95% CI: -2.38 to 3.04) was very large (eta squared = .9).

|

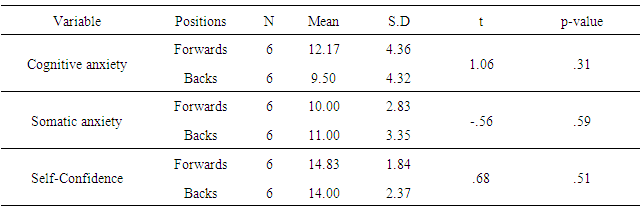

3.3. Second Game: Pre-competitive Anxiety

- An independent – samples t-test was conducted to compare the second game cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and self-confidence scores for forwards and backs. Table 3 shows that there was no significant difference in cognitive anxiety scores for forwards (M=12.17, SD=4.36) and backs (M=9.50, SD=4.32; t (12) =1.06, p=.31, two-tailed). The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference = 2.67, 95% CI: -2.92 to 8.25) was very small (eta squared = .01). Table 3 also shows that there was no significant difference in somatic scores for forwards (M=10.00, SD=2.83) and backs (M=11.00, SD=3.35; t (12) =-.56, p=.59, two-tailed). The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference = 1.0, 95% CI: -4.99 to 2.99) was very large (eta squared = .9). Finally, there was no significant difference in scores for forwards (M=14.83, SD=1.84) and backs (M=14.00, SD=2.37; t (12) =-.68, p=.51, two-tailed). The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference = .83, 95% CI: -1.891 to 3.56) was very large (eta squared = .9).

|

4. Conclusions

- Previous researchers imply that competitive anxiety is the source of decrease in performance especially in amateur athletes [13]. For instance, university team athletes by controlling their competitive anxiety through mental skills like goal setting have higher motivation [14]. In this pilot study, university rugby sevens players had a decrease in cognitive anxiety and somatic anxiety before the first game and second game during the competition. Additionally, the present results indicated no significant difference in self-confidence level among the players from the first game to second game. However, the present study determined that there were no significance different pre-competitive anxieties between forwards and backs positions. It is probable the cognitive anxiety and somatic anxiety were perceived as something with slightly negative influence on their game preparation and opponent to play. Previous researchers also indicated that level of cognitive and somatic anxieties increased and self-confidence decreased between 2 hours and 30 minutes pre-competition in athletes including rugby players’ [7]. These results are consistent with the results of the present study when the cognitive anxiety and somatic anxiety in the first game are higher than the second game during the competition and no difference in self-confidence. The possibilities of different pre-competitive anxiety levels may depend on the level of experience. The competition level may affect the pre-competitive anxiety of the players [13], the present study did not investigate the relationship between anxiety level and games performances The present study indicated that pre-competition anxieties (cognitive and somatic) had decreased from first game to second game in the same tournament. Previous study has acknowledged that positive effects could be brought by competitive anxiety on rugby players [15]. Another study also believes that higher level of competitive anxiety would experience early burnout and decrease the performance of the athletes [16]. However, there is comparative study to determine the relationship between pre-competitive anxiety and mood throughout the games (preliminary rounds and final rounds). Previous researcher indicated that the most important factors which reduce game performance are lack of concentration, weak performance in competitions and sufficient self-confidence [17]. It is probable that the most applicable strategy in the effort of controlling factors which lead to failure in athletes’ performance are by exercising mental skills and applying them when in competition. Based on previous research, athletes who are able to control their tension and deal with conditions that are stressful before the competition would increase performance [18]. Applicable strategies should be maintained during training sessions by the coaches to control and modify anxiety and tension prior to competition. Further research should follow the impact of psychological skills training on pre-competitive anxiety and mood (i.e., positive and negative moods) and associate with the performance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- The author would like to thank Healthy Generation Malaysia, the coaches and players for the support and cooperation in completing this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML