-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(2): 39-46

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.01

Predicting Alcohol Use in a Cohort of College Students Based on Psychological Mindedness, Counseling, and Demographic Variables

Elena Ferrer , Ray Marks

Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College Columbia University, New York, USA

Correspondence to: Ray Marks , Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College Columbia University, New York, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Past research suggests college drinking is extremely widespread and the effects are detrimental with possible deadly consequences. The purpose of this study was to determine whether meaningful associations exist between Alcohol Use, Psychological Mindedness (PM), PM Subgroups, Counseling, and Demographic variables. This cross-sectional study involves a comprehensive demographic survey, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, and the Psychological Mindedness Scale Survey. The result of this study showed that the relationship between Awareness of Oneself (PM Subgroup) and Alcohol Use was negatively associated (r = -.183, p = .016, p < .05) as well as between Counseling and Alcohol Use. The relationship between Age and Alcohol Use was negatively associated. A positive association was found between White students and Alcohol Use (r = .151, p = .047, p < .05), and between Religion and the consumption of Alcohol. The association between College Level and Alcohol Use was positive. The relationship between Risk Takers and Alcohol Use was positively correlated (r = .220, p = .004, p < .01). Risk Takers are at risk for consuming alcohol. Psychological Mindedness was negatively related to alcohol use. This study concluded that among this cohort of college students, those who are Risk Takers, Whites, Senior, Females with Religion, and Older are at risk for Alcohol Use. Those with Awareness of Self are at lower risk of consuming alcohol. Psychological Mindedness may hinder the consumption of alcohol.

Keywords: Alcohol Use, College Students, Mindedness

Cite this paper: Elena Ferrer , Ray Marks , Predicting Alcohol Use in a Cohort of College Students Based on Psychological Mindedness, Counseling, and Demographic Variables, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 39-46. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160602.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Alcohol use has been a serious concern on colleges for many years and is extremely widespread (NIAAA, 2014, Hingson et al., 2009). Evidence of this problem is the well documented past research on the extent of alcohol users on campuses which leads to negative and fatal consequences. For instance, among full-time college students in 2012 the prevalence of annual alcohol use was 77.3% (SAMHSA, 2012, NSDUD, 2012). In addition, research reveals that each year, college students between the ages of 18 and 24 are injured and die (599,000 and 1,825 respectively) from alcohol-related injuries (NIAAA, 2014). Finally, although alcohol abuse is one of the most common reasons for college students to visit counselling centres, they may not always find a counsellor available or the centres open, and/or 32 percent of centres report having a waiting list at some point during the school year (Novotney, 2014). Extensive past research also links college student alcohol consumption rates to behavioral, environmental, biological, and social determinants as risk factors on campuses (Geels et al., 2013; Lorant et al., 2013, Nees et al., 2012, Walker & Stephens, 2014). Likewise, prior studies have associated alcohol use with psychological determinants, and mindfulness is one of psychological predictors that has been explored in association with alcohol relapse prevention (Bower et al., 2014). Previous research has also investigated the relationship between age and number of years in college regarding alcohol use. However, to our knowledge no study has examined the relationship between alcohol use, age, number of years in college and psychological mindedness (a specific psychological determinant). Literature on epidemiology has also examined the relationship between ethnicity and alcohol and revealed that Caucasian/White individuals drink more than other groups in College (Abbey et al., 1998). But none of these past studies examined the relationship between alcohol use and Psychological Mindedness (PM). This is hard to explain given the fact that PM is associated with awareness of cognitive and affective processes (Beitel et al., 2005), is related to capacity for behavioral change (Conte et al., 1995), and is relevant to mental health, physical functioning, and in taking appropriate preventive actions (Denollet & Nyklicek, 2004). Furthermore, some of the findings in PM studies have shown that the levels of awareness and capacity for change are larger in individuals with higher PM than with lower PM (Beitel et al., 2004; Beitel et al., 2005; Conte & Ratto, 1997). Specifically, Awareness of Oneself is a psychological state in which people are aware of their traits, feelings and behaviour (Crisp & Turner, 2010) and perhaps a good attribute for preventing alcohol use. Laterally, past research have shown that college students have been tested in Counselling (such as Brief Interventions) to reduce drinking in different types of settings (Amaro et al., 2010). Some of the counselling techniques have used mindfulness, but there is a distinction between psychological mindedness and mindfulness. Psychological mindedness (PM) includes a “general attentiveness plus an interest in psychological conceptualization…and mindfulness, then, may be a necessary precondition but no sufficient condition (p.747)” (Beitel et al., 2005). Therefore, it follows that if mindfulness alone is used for alcohol prevention, then psychological mindedness (that includes mindfulness but has, in addition, other positive components) could be a better psychological predictor and more helpful in preventing individuals from using and abusing alcohol. These past findings form the basis for presently examining some components of psychological mindedness (PM) and Counselling attendance among college students. The combination of these factors may have a vital role to play in the prevention of alcohol consumption. While previous studies have examined PM and also different types of counselling interventions, to our knowledge no studies have tested the effects of attending counselling among those students who are aware of themselves (a component of high PM) or those who are risk takers for negative behaviours (a component of low PM and impulsivity). Psychological Mindedness (PM) and Awareness of Oneself The structural model of PM as outlined by Beitel, Blauvelt, Barry, and Cecero (2005) provides a practical guide for the conceptualization of PM. According to Beitel et al., the structural model of PM is a three-dimensional model with eight components: (1) Interest in being Aware of Cognition, (2) Interest in being Aware of Affect, (3) Interest in Understanding Cognition, (4) Interest in Understanding Affect, (5) The Ability to be Aware of Cognition, (6) The ability to be Aware of Affect; (7) The Ability to Understand Cognition, (8) The Ability to Understand Affect. Regarding the complete PM structure, Beitel, Blauvelt, Barry, and Cecero (2005) indicated that it is improbable for any researcher to study all the components simultaneously due to the comprehensive nature of the model. In general, PM has been defined as “a person’s ability to see relationships among thoughts, feelings, and actions, with the goal of learning the meanings and causes of his experiences and behaviour” (Applebaum, 1973, pp. 35-46). In addition, Fenigstein (1997) reported that PM involves awareness plus an interest in explaining the objects of awareness in psychological terms. Investigating PM and Awareness even further, Beitel, Ferrer, and Cecero (2005) revealed that Awareness of Self-Awareness is a necessary precondition of PM and a component of PM.

1.1. Psychological Mindedness (PM) and Risk-Taking / Impulsivity

- Applying the Big Five personality traits measured with the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (Costa McCrae, 1992) to predict PM, Beitel and Cecero (2003) found that PM was negatively correlated with neuroticism, one of the sub-scales of the NEO-Five Factor Inventory that display Impulsivity as one of the facets. Impulsivity or Impulsiveness is an important psychological construct and a focal point for the theories of substance use (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) and is related to Risk-Taking (Depue and Collins, 1999). Extreme risk-taking (lack of reflection between environmental stimuli and individual responding during decision making) is linked to drug addiction (Bechara, 2003; de Wit, 2009; Doob, 1990; Xu, Korczykowski, Zhu, & Rao, 2013).

1.2. Goal of the Present Study

- The present study was designed to determine whether meaningful associations exist between Alcohol Use, Psychological Mindedness (PM), Counselling, and demographic variables. Alcohol Use and Non-Alcohol Use across Age, Gender, Ethnicity, College Level and Religion variables were also explored.

1.3. Hypotheses

- This study hypothesized that among this cohort of college students: (a) PM would be negatively/inversely associated to Alcohol Use; (b) “Awareness of Oneself”* would be negatively/inversely related to Alcohol Use; (c) There would be a positive/direct association between “Risk Takers”* and Alcohol Use; (d) Attending Counselling would be negatively/inversely associated with Alcohol Use; (e) Age and Alcohol Use would be negatively/inversely associated; (f) A negatively/inversely relationship would be found between College Level and Alcohol Use; (g) The White/Caucasian group and Alcohol Use would be positively/directly associated; (h) Having a Religion would be negatively/inversely related to Alcohol Use; (i) Alcohol Use will be predicted based on PM levels, Counselling attendance, Age, College Level, and Religion beliefs. *“Awareness of Oneself” and “Risk Takers” are 2 subgroups of items from the PM Scale.

2. Methods

- The present cross-sectional study used data obtained from a 2010 survey of 244 undergraduate students (females=155, males=86) from a Midwest College in the US. The sample included students of at least 18 years of age. IRB approval was obtained from the college and all eligible subjects were required to provide informed consent. Fliers were posted around this college that agreed to participate to notify students about the new study and they were asked if they wanted to participate. Moreover, professors were informed about the research and plans for data collection. And experienced collaborator collected the data at this Midwest College. Completing the questionnaires took effect in rooms prepared for this project. Students were arranged in a way that they could maintain a certain distance between themselves to protect the privacy of the responses. The participants were not paid. More, the students’ confidentiality of data was guarantee by identifying the respondents by number, not by name. Data was collected anonymously. Data material was deposited in a locked cabinet.After disclosing the nature of the study and its risks by an independent experienced agent, the participants who all provided informed consent were administered several questionnaires designed to answer the study questions in a systematic manner. The first survey was a demographic one. The second questionnaire was related to alcohol use (AUDIT) (Saunders, 1993). The third questionnaire was related to psychological mindedness (PM) using The Psychological Mindedness Scale (Conte et al., 1990). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a 10-item self-report scale developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the early identification of problem drinkers. This measure is scored by allocating a score of 1 or more on Q2 or Q3, which indicates consumption at a hazardous level. Any points scored on Q7 throughout Q10 indicate that alcohol related harm is already being experienced. Demb and Campbell (2009) reported that when AUDIT instrument is assessed with college students, the reliability coefficient (internal consistency Cronbach’s Alpha) value was found to be between .74 and .84. According to Babor et al. (2001), AUDIT is extremely reliable when it comes to assessing alcohol addiction. The Psychological Mindedness Scale (Conte et al., 1990) chosen was a 45-item self-report measure. It is scored by totalling all the individual item scores and dividing the total by the number of items. Items display a 4-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Five experienced clinicians were asked to assess content validity of the PM Scale as it was being developed (Beitel et al., 2004). Conte and colleagues (1990) indicated you’re the clinicians agreed that each of the 45 items established a connection with the construct of PM “as they understood it clinically and as it is described in the literature” (p, 428). The reliability of the instrument is r=.92 (Conte et al., 1990). The internal consistency α= .87 (Conte et al., 1990). After the data was acquired, the dataset was entered onto a computer spreadsheet using IBM SPSS 22.00. The power analysis for this study was performed with GPOWER (Erdfelder, Faul, & Buchner, 1996), a widely available power calculator. Power was set at .80 and alpha set to .05. A medium-size was found for our 244 participants recruited for this study. In dealing with the data two procedures were applied, data screening and data analysis. The data screening included an inspection of the descriptive statistics and procedures to establish the accuracy of the data input variables. Following this first step descriptive statistics was analysed to report the mean, standard deviations, frequency and percent. Third, the psychological mindedness (PM) Scale was subdivided in group of items, and the Cronbach’s alpha analysis was performed to examine the internal consistency between each group of PM items (the alpha on each group of items was higher than .70). The total PM Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .82. Out of several groups that emerged with moderate/high internal consistency, two distinctive ones were selected in this study due to the goal of this study: “Awareness of Oneself” and “Risk Takers”. Third, a correlation analysis was conducted to see if some association between variables stood out. As fourth step, Pearson Product-Moment correlation test and regression analysis was utilized to examine the strength of the relationship between alcohol use, psychological mindedness (two subgroups of the PM Scale), Counselling, and demographic variables (Age, College Level, Religion, Ethnicity). Significance was set at p< .05. Finally, a Multivariate Regression Analysis was performed in order to assess whether or not the model was good to explain variation in the dependent variable.

3. Results

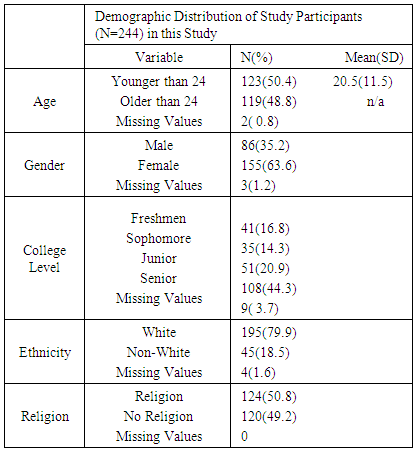

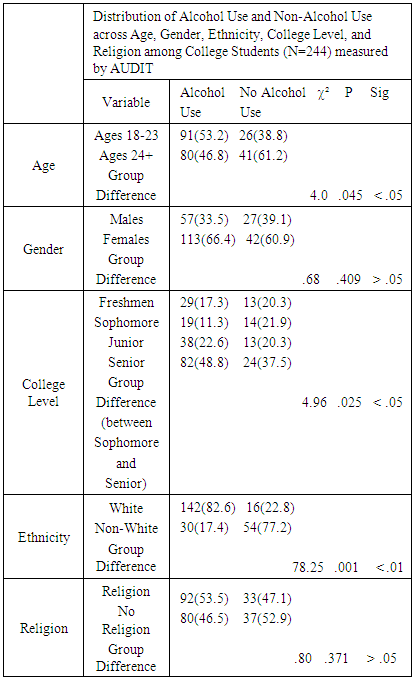

- The study variables (two of them transformed) were neither skewed nor kurtotic. This result suggests that the variables met the assumptions for normality. The relationship between variables was found to be linear.A total of 155 women and 86 men were studied. The majority was female (63.6%) and most were non-Hispanic whites (79.9%). The results showed that 48.8% were 24 years of age or older. Detailed characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. Regarding Alcohol Use and Non-Alcohol Use across Age, Gender, Ethnicity, College Level, and Religion among college students this study revealed that: There is a significant difference between the age groups (18-23 vs 24+) between sophomore and senior students, and between Caucasian and Non-Caucasian (Table 2).

|

|

3.1. Results for Hypotheses

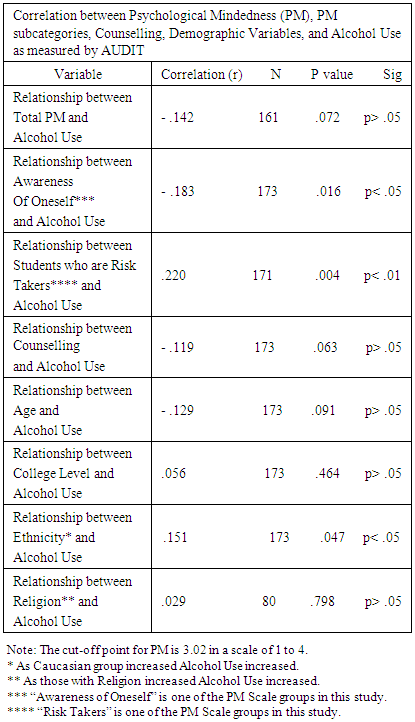

- Results for Hypothesis (a). As predicted, Psychological Mindedness (PM) and Alcohol Use were found negatively/inversely related.Results for Hypotheses (b) and (c). As anticipated, the relationship between “Awareness of Oneself” and Alcohol Use was negatively/inversely related at significant level (r= -.183, p= .016, p< .05 (see Table 3). The correlation between “Risk Takers”** and Alcohol Use was positively / directly associated at statistical significant level (r = .220, p = .004, p < .01) (see Table 3).

|

|

4. Discussion

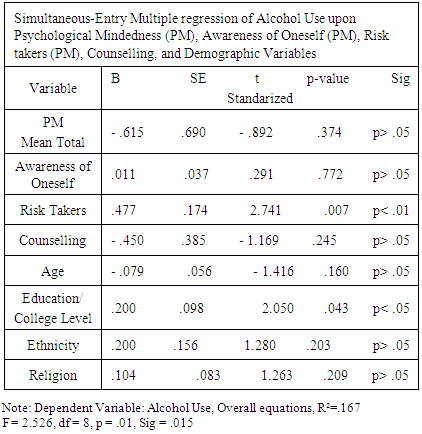

- The main goal of this study was to examine the empirical association between Alcohol Use, Awareness of Oneself (a PM component), Risk Takers (another PM component), Counselling, Age, College Level, Ethnicity, and Religion to expand the knowledge on the predictors of consumption of alcohol due to the prevalent problems of alcohol use in the US. All the directions of the associations proposed were supported except for one. Three correlations were found statistically significant and those significant associations may have an important impact in health and in psychology. In relation to the characteristics of participants, the annual frequency of alcohol use among college students by employing The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was 71.1%. This percentage is smaller than the findings of 2012 SAMHSA that showed that 77.3% of college students have tried alcohol at least once in their lifetime. The gap between the two percentages might be due to the age considered in each investigation (past research and present study). In the SAMHSA report, the age range was 18 to 22 versus this current study, where the age range was18+ years. Because drinking tends to peak in young adulthood between the ages of 18 and 22 (NIAAA, 1997), it could be reasonable to assume that alcohol consumption (in the 18+ range) decreased in those with higher ages in this current study. Another reason for the lower rate of alcohol consumption in the present study was that compared to other states, this Midwestern state where the study took place has substance abuse indicators that are moderately low compared to other states (Epidemiology Profile of Substance Abuse, 2010). Regarding gender one finding is salient in this cohort of college students: The frequency of drinking among females is substantially larger than males (66.4% in females versus 33.5 in males). Although traditionally males have tended to drink at higher rates than their females counterparts, new evidence show that alcohol use among women is increasing steadily (World Health Organization, 2014) which is consistent with the findings in this present study. Furthermore, our results are in agreement with Grucza et al. (2008) who found that binge drinking has increased among women in college. In relation to hypothesis (a): PM total and Alcohol Use was found negatively/inversely associated but not at significant level. The lack of strength in this relationship is probably due to the social pressure beyond the individual mental power. In the United Kingdom research has been conducted about the concept of PM beyond the individual. Seager (2006) and Hewitt, Orbachs, Samuels, and Sinason (2007), took into account not only individual traits but relational and environmental causes. If alcohol is used in college, peer pressure could potentially overpower the individual’s strength not to consume alcohol. Furthermore, PM is multidimensional (Hall, 1992) and some aspects of PM could prove to be different in some subgroups as opposed to general PM as a whole. That could explain why that prediction was confirmed when hypothesis (b) was explored. Participants who reported higher “Awareness of Self” (subgroup among high PM items), and an interest in the psychological processes of their own behaviour also tended to consume less alcohol than those with lower PM at significant levels (r= -.183, p=.016, p< .05). These results suggest that is reasonable to assume that those with higher awareness of self are more able to employ cognitive resources to facilitate their own psychological adjustment that prevents him or her from consuming too much alcohol. This is in line with the studies of Beitel, Ferrer, and Cecero (2005) and Cecero, Beitel, and Prout (2008) that reported that psychological mindedness is related to an increment in coping abilities and a reduction in levels of personal distress. This multidimensional aspect of PM (Hall, 1992) takes on an even more robust degree of importance when we explore hypothesis (c), in which it was found that the relationship between Risk Takers and Alcohol Use was positively/ directly correlated (r = .220, p = .004, p < .01).Although the relationship between Psychological Mindedness (PM) and Alcohol Use has been hardly explored, the findings in this study are in line with the investigations of Allen (1996) and Walton and Roberts (2004) who found a link between heavy drinking and lack of personality traits such as cautiousness, dutifulness and impulse control which are concepts related to PM. In exploring hypothesis (d), it was also confirmed that as Counselling for drug use increases, alcohol consumption decreases. However, the association was not significant. This could be due to the variety of psychotherapeutic approaches attended by students that may have led to different outcomes, some more beneficial than others regarding alcohol use. For example, there are several approaches such as psychotherapy, behaviour therapy, drug abuse counselling, cognitive-behavioural therapy, 12-step facilitation therapy, etc. (SAMHSA, 2014). Some approaches are more effective than others for the treatment of alcohol use disorders. Hypothesis (e) was supported, as students in this cohort tended to consume less alcohol as age increased. The results are inconclusive when compared to some past research. For example, the findings in this study are in agreement with White et al. (2002) but were not in line with the report of SAMHSA (2013) in which showed that college students between the ages of 18 and 22 are more inclined to drink alcoholic beverages as they reach the age of 22. The SAMHSA report (2013) did not mention how alcohol drinking affected college students over the age of 22. In assessing hypothesis (f), the association between College Level and Alcohol Use was found to be positively/directly associated. This means that as the year of college increased, Alcohol Use also increased, which at first glance seemed contrary to our prediction. However, once we explored a bit further and examined descriptive statistics, we found that the increase in alcohol consumption compared to the college level does not have a clear cut pattern since sophomore students were the ones who drank less frequently among all college students. As predicted in hypothesis (g), being identified as belonging to a Caucasian group and Alcohol Use were positively/directly associated. This is in agreement with some past research that indicated that being White is a risk factor. For instance, our findings are in line with the findings of the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism (NIAAA, 2006) which reported that among the US population current drinkers White/Caucasians have the highest rate in Alcohol Use. It is also in agreement with the studies of Michel Fleming (2002). The examination of hypothesis (h) suggested that the association between having a Religion and Alcohol Use was positively/related directly in this sample. This is a surprising finding at first given past research such as that by Lisa Miller (2000) found that low levels of religiosity may be associated with adolescent onset of substance use and abuse including alcohol. However, if we take a look at the difference between males and females, having a Religion was found to be negatively/inversely associated with Alcohol Use in males, which is line with past research. The findings of this study seem to suggest that in this particular cohort of college students, males have lower risk for consumption of alcohol than females. After all the variables were entered in the Simultaneous Multiple Regression, it was found that Alcohol Use was predicted by variables such as Risk Takers (items in the low PM subscales), Caucasian, College Level, and those with Religion. The result suggests that among this cohort of college students in the Midwest, those who are Risk Takers (subgroup of Low PM), Whites, senior students, and females with Religion are at risk for Alcohol Use. Higher PM may hinder the consumption of alcohol, especially those with higher self-awareness. These findings are relevant to college student’s health. One implication might be that all students entering in the senior year (who are White, Female, and have a Religion) be screened for Alcohol Use. Furthermore, given that past literature indicated that counsellors are not always available in campus, academic institutions of higher education should address this problem more often and put in place policies in which college counselling centres could be available 24 hours a day. There are two key limitations to the present study. First, primary data for this study originated from a sample of Midwestern college students, and the findings may not be generalizable to other college students in the US. Second, this study employed a large sample of women compared to men. Future investigations might explore the variables of PM and Alcohol Use in a larger, balanced sex-ratio sample of college students. Furthermore, in the future performing a replica of this present study (using a sample of college students from the northeast of the US) and a comparison analysis between the two studies (present and future) could shed some light on how the prediction of psychological mindedness on alcohol use might be generalized to a greater population in the US. The current study is a first step in the process of understanding how psychological mindedness could predict alcohol use among college students.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML