-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(1): 14-19

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160601.03

The Green-Eyed Monster: Exploring the Associations of Ego Defenses and Relationship Closeness on Romantic Jealousy

S. Sahana, D. Barani Ganth

Department of Applied Psychology, Pondicherry University, India

Correspondence to: D. Barani Ganth, Department of Applied Psychology, Pondicherry University, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

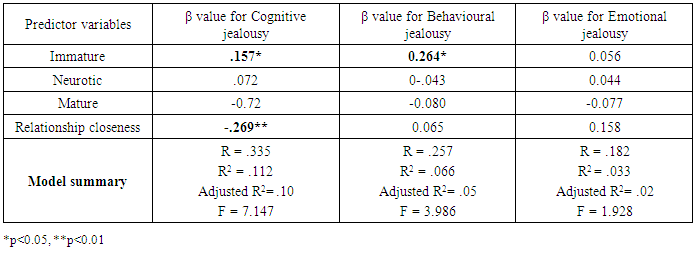

The present study explores the relationship between ego defenses, relationship closeness and romantic jealousy. The study was done with a sample of 231 individuals (falling within 18-32 years) out of which 127 were female and 104 were male. Results of the study revealed that there was a gender difference only in terms of cognitive jealousy with men showing higher levels of the same. However no differences were found when it came to emotional and behavioural jealousy or relationship closeness. Also people with a romantic partner were found to be high in relationship closeness compared to those without a partner (those who just show romantic attraction for someone). Correlations between these variables showed that immature defenses showed a positive association with cognitive and behavioural jealousy. Mature and neurotic defenses showed no correlation with jealousy. Relationship closeness showed a negative correlation with cognitive jealousy and a positive correlation with emotional jealousy. Regression analysis showed that relationship closeness emerged as the best predictor of cognitive jealousy and immature defense style was found to be the best predictor of behavioural jealousy. However the regression model was not significant for emotional jealousy.

Keywords: Romantic jealousy, Relationship closeness, Ego defenses

Cite this paper: S. Sahana, D. Barani Ganth, The Green-Eyed Monster: Exploring the Associations of Ego Defenses and Relationship Closeness on Romantic Jealousy, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 14-19. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160601.03.

1. Introduction

- Romantic jealousy can be defined as an aversive emotional reaction that is followed by thoughts, emotions and actions towards an imagined or a potential rival who threatens the quality or the existence of the romantic relationship (White & Mullen, 1989). It has a powerful impact on the relationship as jealous partners engage in tactic and dynamics which involve inducement, appeasement and reward to the partner to make the partner avoid ‘seeing’ the rival. It has been found that romantic jealousy is the primary motive behind partner violence and homicide (Wilson & Daly, 1998). It also, at times, involves violence or threats of violence and self harm.Jealousy arises most of the times due to some kind of uncertainty, insecurity (Brown & Moore, 2001; Buunk, Park , Zurriaga, Klavina & Massar, 2008) or a threat which can either be self or external threats (Buunk, Solano, Zurriaga & Gonzalez, 2011 ; Desteno , Valdesolo & Barlett, 2006). The feelings of insecurity, developed mainly due to perceived lack of attention and threat of rejection by one’s own partner and possessiveness, takes a huge toll on the pleasure and joy in a romantic relationship (Salovey & Rodin, 1984) and researchers suggests a rational response from the partner to reduce the negative effects of jealousy. Nevertheless, jealousy is also viewed as positive aspect in relationship, before it grows out of proportion (Brehm, 1992). Evolutionary psychologists view romantic jealousy as an adaptive mechanism wherein it motivates actions to retain the partner exclusively for one’s own sexual access (Buss, 1995). Thus jealousy serves to avoid infidelity among mating partner.Scientific literature on romantic jealousy reveals that gender difference is one of the striking aspects in understanding jealousy. It is understood from such studies that men react more to sexual infidelity and women are said to react to emotional infidelity. (Scelza, 2013; Schutzwohl & Koch, 2004; Schutwohl, 2008; Shackelford et al., 2004). Gender difference was found also in ways in which partners handle and cope with jealousy. Women tend to use more constructive ways to cope with jealousy than men (Brehm, 1992; Carson & Cupach, 2000; as cited in Demirtas-Madran, H. A., 2011). Relationship researches have proposed that women tend to preserve the relationship in the context of jealousy while men on the other hand seek destructive methods of coping in order to preserve their self-esteem (Bryson, 1991; Rusbult, 1987).Studies linking jealousy with other relationship variables such as dependence in relationship, love styles, defense styles, relationship closeness etc. are sparse. As far as relationship closeness and romantic jealousy are concerned, only a handful of studies have been done exploring these two dimensions. Those studies have claimed that the more the interdependence, the more the threats to relationships caused arousal and thus expressions of jealousy. It was also perceived to be increasingly appropriate as the relationship develops. (Aune & Comstock, 1997). Breaking down jealousy into its different types, it was found that relationship closeness was positively associated with emotional jealousy and negatively associated with suspicious jealousy. Behavioural jealousy was positively associated with two “bad” love styles – Ludus and Mania. (Attridge, 2013). Also jealousy was seen to be positively correlated with immature defenses and negatively correlated with mature defenses. Adams (2012) found that the relationship between jealousy and defenses was found to be stronger among men than women.Keeping in view of the above literature and variables considered and paucity of studies in exploring the role of such variables on jealousy, the present study was done with the aim of studying the inter-correlation of ego defenses, relationship closeness and romantic jealousy and also to study the extent to which the former two influence the latter. Also this study was done with an intention of learning about the gender differences in jealousy experience and also the differences in the levels of relationship closeness and jealousy experiences between two groups i.e. 1) people with a romantic partner and 2) people without a romantic partner, but show romantic attraction for someone.We hypothesized that men would show higher levels of cognitive jealousy and women would show higher levels of emotional jealousy. People in a mutual relationship would tend to show higher levels of relationship closeness than those who do not have a romantic partner. Jealousy experience among people without a romantic partner would be higher than that of people with romantic partner. We also hypothesize that ego defenses, relationship closeness and romantic jealousy would be significantly related and romantic jealousy would be predicted by relationship closeness and ego defenses.

2. Method

- Participants and ProcedureThe sample consisted of students from a large south Indian university in the age range of 18-25.The data were obtained by two ways. 1) The researcher selected two women’s hostels and one men’s hostel randomly in the university and the questionnaires were distributed to the occupants assuring confidentiality of the responses. In order to maintain anonymity regarding personal details of the participants, the questionnaires were collected back in a bunch in a box and mixed together. 2) Online survey was posted in a social networking platform in the profile of the researcher. To increase the accessibility of the survey, the link of the survey was shared on the profiles of at least 5 more people and was also posted in different groups on the same social network. A total of 244 responses were obtained out of which 13 were invalid. These invalid responses consisted of those who had given incomplete questionnaires and also those who have neither been in a mutual romantic relationship nor have/had been romantically attracted to someone. Thus the total sample size of the study was 231 (87 questionnaires were filled manually and 144 were filled online) out of which 104 were male and 127 were female. Measures Romantic jealousy Romantic jealousy was assessed using Pfeiffer and Wong’s (1989) Multidimensional jealousy questionnaire. This questionnaire divides jealousy into three types: cognitive, behavioural and emotional jealousy. Example items that measure cognitive jealousy are “I suspect that X is secretly seeing someone of the opposite sex”, “I am worried that some member of the opposite sex may be chasing after X”. Examples of items measuring emotional jealousy are “X comments to you on how great looking at a particular member of the opposite sex are”, “X shows a great deal of interest or excitement in talking to someone of the opposite sex”. Examples of items measuring behavioural jealousy are “I look through X’s drawers, hand bags or pockets”, “I call X unexpectedly, just to see if he or she is there”. All these items are measured using a likert scale ranging from 1 to 7, 1 being never and 7 being always. However, for emotional jealousy items the labels were reversed with 1 being very pleased and 7 being very upset. The reliabilities of the cognitive, emotional and behavioural jealousy sub-scales were originally reported to be 0.92, 0.85 and 0.89 respectively (Pfeiffer & Wong, 1989; as cited in Kalbfleisch, (Ed.), 2013).Relationship closeness Relationship closeness was assessed using the Unidimensional Relationship Closeness Scale (URCS) (Dibble, Levine and Park, 2012). It was developed to measure closeness in a single dimension that can differentiate among various levels of closeness for a variety of relationship types. The scale possesses high reliability across relationship types with an alpha value of 0.96 (Dibble, Levine, & Park, 2012).Defense styles To assess the ego defenses of an individual, the shortened version of the Defense Style Questionnaire was used. This questionnaire consists of 40 questions developed by Andrews, Singh and Bond (1993). These defenses described are largely consistent with the glossary of defense mechanisms developed for the DSM-III-R. The authors demonstrated a test-retest correlation ranging from .75 to .85 for defense factors, .38 to .80 for individual defenses and .71 for the mature factor and .60 for the immature factor.

3. Results

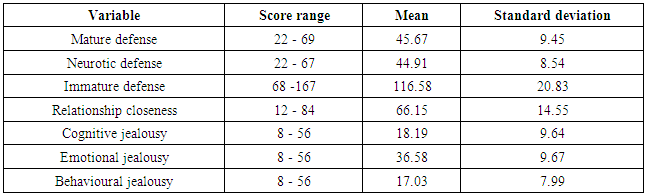

- A perusal of table 1 shows score range, mean score and standard deviation for the selected variables. It is inferred from the above table that the sample shows moderate scores on all the three defense styles. In terms of relationship closeness, the sample shows a higher value of closeness. Looking into scores on jealousy, the sample was found to be on higher side on emotional jealousy, whereas lower levels are shown on cognitive and behavioural jealousy.

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

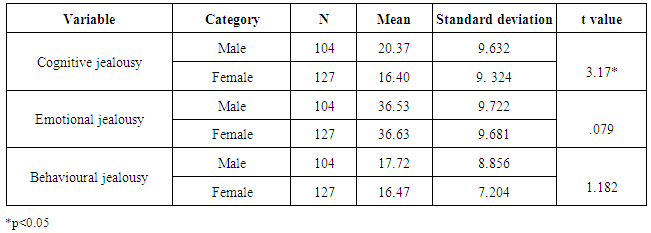

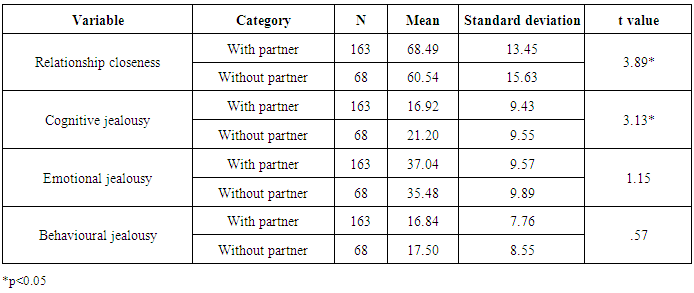

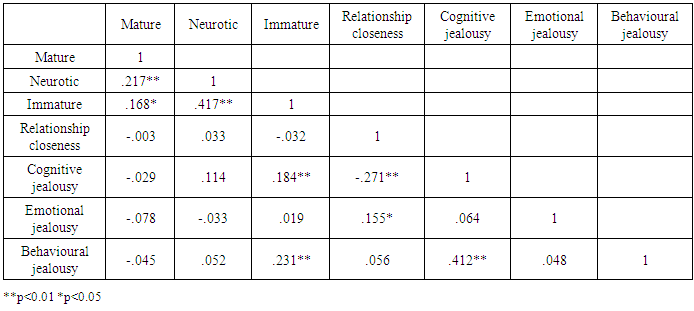

- On looking at the trends in terms of gender difference in romantic jealousy, the present study found gender difference in cognitive jealousy, where men seemed to have scored higher than women. However, though there is no significant gender difference, the current study reports that, emotional jealousy is high among both men and women. As stated earlier, studies on romantic jealousy have been very few and the results are also inconsistent across cultures and regions. For eg, in one study Bringle and Buunk (1986) reported that women were more jealous than men. In contrast, a study done by Mathes and Severa (1981) (as cited in Kalbfleish, 2013) showed that men were jealous of women. Items involving cognitive jealousy mostly involve suspiciousness and jealousy related to sexual infidelity and as found in the present study and in accordance with many studies on jealousy, men tend to show more such jealousy than women (Scelza, 2013; Schutzwohl & Koch, 2004; Schutwohl, 2007; Shackelford et al., 2004). One possible explanation for differential pattern among men and women comes from evolutionary theories of mate selection. Evolutionary psychologists, based on theories of natural selection, claim that our brain is circuited in such a way that men react most to sexual fidelity and women are innately predisposed to jealousy due to emotional infidelity. (Buss, 1995; Harris, 2004). Mutations that favour in the increase of fitness are inherited by the future generations from successful individuals. Thus ancestral man faced a serious threat from cuckoldry. When a woman is impregnated by another man, then the partner’s scarce resources should be given or shared with his genetically unrelated children, thus making his own Darwinian fitness sink. Thus a man’s brain is wired in a way to react intensely to sexual jealousy so that he will be able to defend himself against this cuckoldry. On the other hand, for the ancestral woman, having the knowledge that she was the mother of her children, faced no such risk and thus, did not face any pressure related to sexual fidelity. However, women developed a reaction to emotional fidelity because human children need years of care and she faced a threat when her philandering mate diverted his resources to another woman and her children. (Schutzwohl, 2004).Present study throws light on dynamics involved in relationship closeness in the context of jealousy across groups involving with or without partner. Individuals with partners obviously would experience higher levels of relationship closeness when compared to those without a partner due to the fact that they always remain in constant contact with one another. Thus with frequent contact, people tend to gain influence over one another’s decisions, emotions, behaviours and they tend to behave or act in ways that works as a compromise for both, in order to maintain a healthy relationship. People without partners, as conceived in the present study, are the ones who are just romantically attracted or those who have been rejected in a romantic relationship proposal. Such people hardly have any control over or sometimes even contact with the other person. They thus show lesser relationship closeness. This might lead to them being paranoid about the one they love. They would thus suspect that their beloved ones might be interested in someone else. Their sense of insecurity about their beloved one is higher when compared to those in a mutual relationship. With regard to differences in terms of romantic jealousy, the results of the present study, shows difference only in cognitive jealousy but not in emotional and behavioral components. One explanation for higher cognitive jealousy among individuals without partner is the absence of partner itself. The potential stress and agony involving jealousy involving a partner could keep the individual away from developing interest in mutual relationship. The lack of difference in behavioral and emotional jealousy might indicate that these dimensions of romantic jealousy do not vary with regard to having a partner or not. This result, though, do not support the hypothesis made, indicate that romantic experiences in the context of having a current partner or not do not vary much, at least for the experience of jealousy. This also shows that jealousy experience, especially at emotional and behavioral level, prevails in all forms of romantic experience even in individuals who had not experienced a mutual relationship involving dyadic exchange of love, affection and communication.The correlations obtained between immature defense and cognitive and behavioural jealousy was seen in previous literatures too (Adams, 2012). Sinha and Watson (1999) found that immature defenses were related to three different measures of personality disorders. This predicted all three measures for avoidant, antisocial, borderline, passive aggressive and paranoid personality disorders. This probably provides good evidence for immature defenses being positively correlated to the two kinds of jealousy. Also, this probably helps us in understanding why it has been positively correlated to that of behavioural jealousy which involves communication of jealousy by acting on it, which involves checking and spying behaviours. The correlation between relationship closeness and jealousy was also in accordance with the study done by Attridge, (2013) which again found that relationship closeness was positively associated with emotional reactive jealousy and was found to be negatively associated with suspicious jealousy which corresponds to the emotional and cognitive jealousy respectively in this study. Emotional jealousy probably arises due to excessive investment of the partner in the relationship in terms of emotional, physical or financial resources. Thus the more the time they spend with their partner , the more close they become and the fear of loss and wastage of resources increases the jealousy in case of a threat. Also emotional jealousy arises when a person considers his/her partner close to one’s own self concept and also to their future plans and so on Cognitive jealousy on the other hand , probably arises when a person spends less time with their partner. The lesser the time they spend, the more the insecurity and the more the fear or the suspicion of infidelity. This makes them extremely sensitive to a rival and they tend to act out their emotions, which will make their partners feel suffocated and thus this will invariably lead to an erosion of relationship closeness. On looking at what predicts jealousy, it was found in the study that immature defense was the most significant predictor. Immature defenses involve acting out, displacement, somatisation, denial, passive aggression, projection etc which all seems to be symptoms or ways in which people try to communicate their jealousy. As explained by Guerrero (1998), ways of communicating jealousy involve face-to-face communication and behavioural responses. Behavioural responses involve, surveillance restriction (spying behaviours), rival contact, manipulation (trying to make the partner feel guilty), violent behaviours towards objects such as breaking things or slamming doors. Also interaction is done in different ways such as avoidance or denial, negative affect expression, active distancing or distributive communication where in a person yells or screams at the partner. Such behaviours show some kind of association with the usage of immature defenses. This also provides explanation for immature defenses being best predictors of jealousy on the whole. This might probably be because such people are the ones that would express jealousy easily.

5. Limitations of the Study

- The present study involved mostly urban students from an institutional setting, which might limit the generalization of findings to other group of students. Also, the study involved cross sectional design and hence causal attributions of jealousy could not be made. Further rigorous studies involving more representational sample should be conducted to understand the group difference in emotional and behavioral jealousy.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML