-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(1): 7-13

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160601.02

Managing Adolescents with Gaming Problems: The Singapore Counsellors’ Perspective

Abigail Hong Yan Loh1, Yoon Phaik Ooi2, 3, 4, Choon Guan Lim2, Shuen Sheng Daniel Fung2, 3, Angeline Khoo5

1Ministry of Health Holdings, Singapore

2Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

3Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

4Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Department of Psychology, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

5National Institute of Singapore, Singapore

Correspondence to: Abigail Hong Yan Loh, Ministry of Health Holdings, Singapore.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Internet use has become an important part of the lives of children and adolescents in modern Singapore, and in this era of online communities and connectivity, problem gaming is emerging as a significant morbidity amongst youth. Correspondingly, cyber wellness services have been established in schools as well as non-government organisations. However, counsellors involved in providing these services come from different backgrounds with varying levels of training and experience. In this study, we surveyed counsellors who work with youths on their perceptions of youth gaming problems, their expertise and identified needs, and the relationship between gaming problems and maladaptive coping and/or social disenfranchisement. The results of this study indicated that most counsellors viewed gaming problems as an outcome as well as a perpetuating cause of social dysfunction and inadequate coping skills, with optimal interventions targeting these two aspects, and as a result, express interest in further equipping of therapy skills to negotiate social supports for such at-risk youths. These were identified as potential areas of further training for counsellors involved in cyber wellness programmes.

Keywords: Internet addiction, Online gaming, Adolescent mental health, Coping strategies, Cyberpsychology

Cite this paper: Abigail Hong Yan Loh, Yoon Phaik Ooi, Choon Guan Lim, Shuen Sheng Daniel Fung, Angeline Khoo, Managing Adolescents with Gaming Problems: The Singapore Counsellors’ Perspective, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 7-13. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160601.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Internet use has become an integral facet of modern life, particularly for the generation of children and adolescents who have grown up in this era of online “villages” and global connections [1]. It has become a central, unavoidable component in areas of academic, occupational and social communication as well as self-expression, and it is precisely due to its pervasiveness in all aspects of daily life that numerous studies have been conducted to investigate its effects on potentially vulnerable populations [1, 2]. The concept of pathological internet use (PIU), also commonly referred to as Internet Addiction, has therefore been a subject of growing interest and concern [3]. KS Young, in her 1996 paper, describes the similarities between the two as “an impulse-control disorder which does not involve a substance” [4], and can be defined as sharing these characteristics: excessive use, withdrawal, tolerance, and negative effects on daily functioning [3]. However, there was disagreement among researchers and professionals in the defining criteria for the condition [5]. Additionally, a variety of related activities are available on the Internet, such as video-gaming. In the decades that follow, alongside technological advances, a variety of related conditions appeared in the literature including ‘Internet gaming Disorder’, ‘smartphone addiction’ [6] ‘smartphone addiction’ [7], and problematic or addictive digital gaming [8]. As such, a universal definition of Internet addiction and agreement on its associated terminology is needed, due to the diversity and ambiguity of the exact constituents of pathological use of the Internet [9]. This proves to be an ongoing and unique challenge in current efforts to further understanding, structure diagnostic frameworks, and construct intervention strategies for affected individuals [3, 9, 10]. In the new DSM-5 edition, ‘Internet Gaming Disorder’ was included in Section III, as warranting further research and clinical data to aid future formulation of a diagnostic criterion, with a presentation and evolution similar to that of the other behavioural addiction: gambling [11]. There is still therefore no unifying term or diagnostic criteria for clinical use, although steps are currently being taken to obtain an international consensus for an approach towards definitions and assessments of internet use related disorders [12]. Comparatively, there is less research on the effective treatment approaches for the group of internet-related addiction problems and whether which will give better longer-term outcomes [13]. Preliminary evidence suggests that education and cognitive behaviour therapy may be effective although more research needs to be done [14, 15].Of the various demographic groups impacted by the effects of pathological Internet use, the adolescent population has been recognised as being particularly susceptible to these effects in light of their developmental life stage, vulnerability to addictive agents, and increased exposure to information technology [16]. Findings in recent studies on the effects of Internet misuse range from excessive time spent online, to its effects on academic performances, to the impact on adolescent psycho-socio-emotional health and development [2, 17]. Of the various forms of PIU, one of the most prominent and widely studied in this group is that of online game addiction [18, 19]. While online gaming, and Internet use in general, can be seen as neutral activities which may have benefits in its own rights, excessive and pathological patterns of use can result in longstanding, far-ranging negative effects on an adolescent’s development and daily life [3, 19]. Possible causative factors implicated in the aetiology of PIU include existing social and relational difficulties, maladaptive coping skills, other addiction behaviours, and high Internet penetration and gadget accessibility [18, 19]. The negative effects are mainly purported to be, but not restricted to: social withdrawal, increased aggression or agitation, affective disorders (including depression), somatic disorders, and problems with executive and cognitive functioning, all of which lead to dysfunction and distress [16-22]. From a local Singaporean perspective, online gaming addiction is gaining prevalence, and is emerging as a significant contributor to morbidity in the child and adolescent community [22]. This is in keeping with the findings of greater rates of gaming problems in Asian populations than even that of developed European countries [17, 19-25]. Singapore is a highly wired nation with Internet connectivity in almost every household [26]. A local study of secondary school students found that 17.1% spent an average of more than 5 hours daily on the Internet [27]. Another study which surveyed primary and secondary school students found the prevalence of pathological gaming to be 8.7% [28], which was much higher than that reported in European adolescents [29]. Accessibility is likely a major factor, with many children having access to smartphones and forming habits of Internet and online game use from a very young age [30]. As a result, local awareness and education efforts have been mooted in government-initiated programmes and publications targeting school-aged children and their families, while mental health and education services are availed to those reporting or presenting with symptoms and effects of Internet addiction [31]. And as counselors and youth workers typically make up a significant number of those dealing with children with Internet and gaming addictions [32], all mainstream primary and secondary schools in Singapore are now staffed by a team of allied educators (including counsellors) who provide social and emotional support for their students for a range of issues, including problematic Internet use [33]. Additionally, the Ministry of Education Singapore provides a framework to guide schools in their planning and implementation of their cyberwellness programmes and activities based on their student profile and school environment [34]. This study therefore aims to present the perceptions of adolescent gaming addictions from the school counselors’ perspective, the challenges of their work with this population, and identifying possible gaps in their training and equipping to deal with the unique issues in online game addiction, so as to help direct current interventional methods and future courses of research.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Nanyang Technological University Institutional Review Board, and the Ministry of Education’s Guidance Branch. A total of 212 youth workers with schools and non-government organisations were invited to participate in the survey for their experience in counselling students with gaming issues and their perceptions of the coping strategies used by the students. They were asked to complete the survey during workshops and conferences from November 2010 to February 2011 by the Institute of Mental Health and CARE Singapore.

2.2. Measures

- 1. Self-constructed survey on counsellors’ perceptions and experiencesThe self-constructed survey explored about the extent of the counsellors’ encounters with students with video gaming issues, their knowledge and expertise, training needs and the kind of intervention strategies used, as well as their perceptions of what strategies students were using to cope with pathological video gaming according to the Adolescent Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences scale (ACOPE) [35]. 2. Adolescent Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences scale (ACOPE) The ACOPE scale is a self-report survey stratified into 12 subscale sets, and was a tool developed to measure adolescent psychosocial adjustment, and the use of mature coping strategies that engaged the social environment [35]. Studies using the ACOPE scales in adolescent populations had shown that the use of mature “salutary” coping strategies, which formulated actions and engaged social support when facing difficult situation, often correlated with more optimally adjusted profiles [35]. The Cronbach alpha calculated for the ACOPE scale was 0.896.

2.3. Data Analysis

- Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0.0.0. To examine perceptions of adolescent gaming addictions, we used descriptive statistics to explore the profiles of counsellors and their involvement with cases of problem gaming. The non-parametric models reported these results as the median range of age and years of experience of counsellors, mean number of students seen for gaming addiction over different time periods, frequency of methods used for assessment and intervention in gaming addiction cases, and frequency of training needs reported by counsellors. For analysis of perceptions of coping strategies, comparing between counsellors and students, independent t-tests were conducted to examine for the differences in strategies on the ACOPE scales, with Bonferroni correction used for each set of analyses, with p-value set at <0.01.

3. Results

3.1. Profile of Counsellors

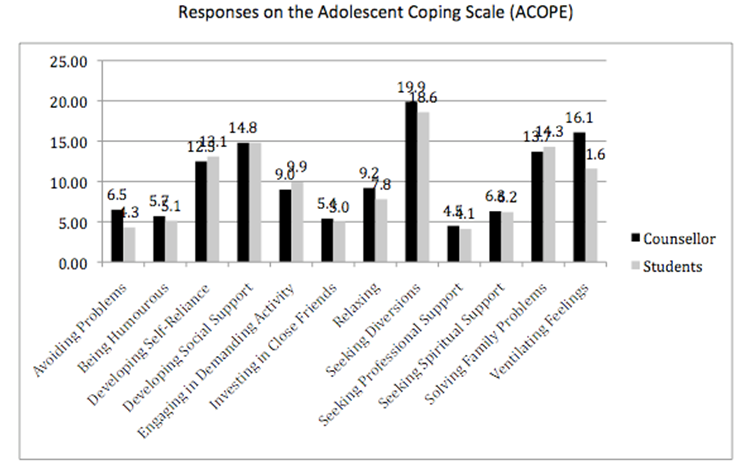

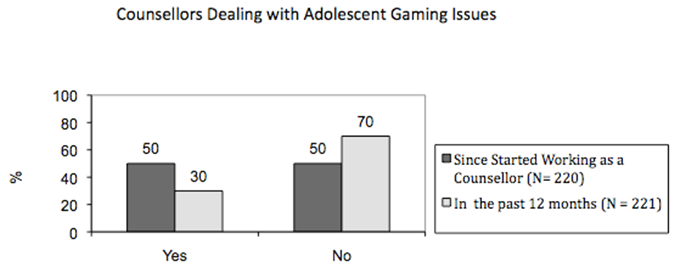

- The ages of participants ranged between 31 and 40 years, with 49% of the participants being school counsellors; the others were made up of teachers and non-school based counsellors. About 64% of the participants stated that they had less than 5 years of experience in counselling.Half of the participants reported that they had provided counselling for a student with pathological video-gaming related problems since commencing their work as a counsellor. In the 12 months prior to the survey, 30% of the participants have provided counselling for a student with pathological video-gaming/gaming addiction (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Percentage of counsellors, educators and youth workers surveyed who had counselled students with gaming issues |

3.2. Counsellors’ Experience with Gaming Behaviours

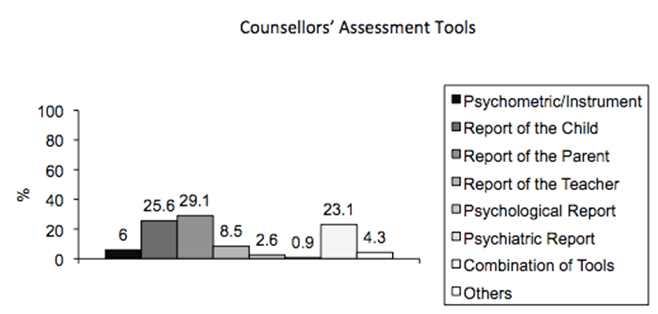

- The average number of students with pathological video-gaming or gaming addiction seen by the professionals since they started working as a counsellor was 2.51 (s.d. = 5.71). The average number of students seen by the counsellors, educators and youth workers in the past 12 months was 0.87 (s.d. = 1.69). The majority of counsellors, educators and youth workers had not counselled students with pathological video-gaming/gaming addiction. The majority of the clients never (32.7%) or seldom (26.5%) raised the issue of their gaming habits during counselling sessions. On the other hand, the majority of the participants (63.1%) asked about their clients’ video gaming habits, with frequency ranging from “Sometimes” to “Most of the time”. The majority (72.9%) of the participants felt that gaming was part of their clients’ broader issues/problems, with responses ranging from “Sometimes” to “Most of the time”.The participants also reported using a variety of assessment methods when assessing students with gaming-related problems. The most commonly used methods included parent report (29.1%) and child report (25.6%). See Figure 2.

| Figure 2. Types of tools used for assessing problem gaming of which parent reports rank highest |

3.3. Perceptions of Coping Strategies

- A series of independent t-tests were conducted to examine the differences in the perception of coping strategies between the counsellors, educators and youth workers and the students. See above: Figure 3.

3.4. Training Needs

- A total of 97% of the participants stated that such training programmes/workshops should be provided to school counsellors, educators and youth workers, and 89% of the participants felt that they needed to attend such a training programme or workshop to help students with pathological video-gaming or gaming addiction more effectively. 77.3% of the participants exhibited interest in training programmes / workshops on definitions, concepts, prevalence and scope of pathological video-gaming behaviours, and 93.2% of the participants showed interest in training programmes / workshops on how to assess children’s and adolescents’ pathological video-gaming. 85.1% of the participants were interested in training programmes/ workshops focusing on information about referrals, and 96.6% of the participants were interested in training programmes/workshops on intervention modes for children/ adolescents with gaming problems.

4. Discussion

- Findings from our study indicate that most of the counsellors, educators and youth workers, who participated in the study, perceived themselves to be inadequately equipped with necessary knowledge and skills to address their clients’ issues of pathological video-gaming when they had seen cases with pathological video-gaming issues; at the same time, majority (73%) of the respondents perceived that gaming problem was part of their student client’s broader issues, and that gaming behaviours made up a significant proportion of the problems their clients were undergoing.There was no significant difference in most of coping strategies perceived to be used between counsellors and students. However, the coping strategies the counsellors perceived from their clients did not seem to fully correspond to what these professionals reported to be actually practicing to help the adolescents. That is, while the main coping strategies these professionals perceived from their clients included developing social support and solving family problems, their intervention approach seemed to be mostly at the individual client level, with only a small percentage of counsellors employing family counselling methods. The majority (64%) reported using individual counselling as the main mode of their counselling intervention using behavioural-modification approach or other similarly individualised client-based approaches. Both child and/or parent reports on pathological video-gaming were also used for assessment of online gaming issues, with more than 50% of counsellors reporting their use in their interview processes. In studies across various cultures and subgroups, parental and family involvement have been shown overall to reduce pathological Internet use and gaming behaviours [36-39], with greater positive predictors in parent-child bonding and closeness as opposed to access restrictions and parental security practices [36, 39]. Hence, such findings highlight the importance of focusing of parental factors and family functioning as both predictors and intervention avenues in adolescents presenting with problem gaming habits.The counsellors, educators and youth workers’ conceptualization of poor social functioning as an indicator of pathological video-gaming in the interview study appeared to be somewhat congruent with their perception of main coping strategies adopted by student clients, such as avoiding problems, seeking diversions, and ventilating feelings – all of which tended towards “stress palliation” or “tension reduction” [35]. The problem of pathological video-gaming can be recognized as a social function or social skills issue, which can imply that the assessment and intervention utilized by the counsellors should focus on understanding, mobilizing, and enhancing their clients’ social environment, personal relationships and social skills; these in turn may counteract problems with interpersonal relationships and resulting social anxiety that may predispose to Internet addiction [40]. The other positive implication is that the counsellors, educators and youth workers who participated in the study seem keen to learn how they themselves can directly process the assessment and intervention for clients with pathological gaming behaviour, rather than merely refer their clients to other professionals.There were several limitations to this study, foremost being that the survey results only studied the profiles and perspectives of the respondents. This could give rise to inherent bias in the types of responses as seen on the survey results, and may not be as accurately generalised to the larger community of Singapore youth counsellors and clients. That the study had kept to a specific population, i.e., only the counsellors, also highlights methodological limitations in the application of the instruments used; the ACOPE assessment tool, largely used as a self-report tool for adolescent participants, is not a validated instrument for use by assessors of adolescent patients, and hence there is possible inaccuracy in the scoring of coping methods by external parties. However, this was done in an attempt to reduce responder burden, and to keep the focus on the study population of school counsellors. The nature of using a survey may also be a limitation in its recall bias, which may inadvertently skew results. The lack of a definitive concept or agreed definition of the terms “gaming addiction” or “Internet addiction”, as well as the cohort selection of specifically the mental health workshop attendees are other contributors to study bias that may also compound the recall bias and data inaccuracies.In terms of future direction, gaming behaviours need the attention of all parties involved in working with children and adolescents. Counsellors, educators and youth workers need to ask their clients about their gaming behaviours to see if this is related to the problems which they first present at the counselling sessions. More may need to be done with regards to training of counsellors, educators and youth workers in group counselling that involves peer and family support. The counsellors’ needs regarding trainings and workshops on assessment and intervention skills, (rather than generic information and knowledge about pathological video-gaming) for clients with pathological video-gaming were clearly expressed; hence, training or workshop programmes on assessment of pathological video-gaming and intervention strategies need to be designed to effectively engage students, and their parents and teachers in the process, with the aim not only to reduce the symptoms of pathological video-gaming but to improve social functioning and skills ultimately within the context of their social environment. Familiarising and utilising new media, such as social networking sites, could also be another potential intervention and outreach avenue for those working with youth to engage and communicate with them through such means.For future potential studies, more longitudinal research needs to be done to understand these protective and risk factors, not only to understand long-term effects of video gaming but also those that include patterns of family relationships involving same-gender and cross-gender interactions. Also needed are studies on the nature of parental control involving setting of limits, monitoring of compliance, mediation through discussions and co-playing, different parenting styles, and the role of different caregivers. Research needs to be done to identify factors that impede change in the clients, as well as those that led to changes and contribute to successful interventions. Subsequently, further studies should be carried out on existing gaming intervention programmes, and how new research findings can further improve their efficacy.

5. Conclusions

- Gaming problem behaviour is an emerging issue among Singapore adolescents that is likely to have associations with poor social functioning and maladaptive coping mechanisms. The survey of counsellors who work with such youths also gives evidence of the growing concern of the morbidities and dysfunctions that can arise from such behaviours. Unsurprisingly, the majority of these counsellors are therefore keen for further training and equipping in skills to assess and identify these youths in need, as well as to target the initial trigger point of such behaviours as possible treatment avenues, primarily in the development of mature coping styles and robust social supports as means to combat gaming addictions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The respective authors for this paper declare that there is no conflict of interest for disclosure. No competing financial interests exist.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML