-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences

p-ISSN: 2163-1948 e-ISSN: 2163-1956

2016; 6(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160601.01

Weight Perception, Body Size, Self-Esteem and Social Anxiety in Obese Adolescents: A Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) Model

Can Jiao , Ding Yan , Ting Wang

College of Psychology and Sociology, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

Correspondence to: Can Jiao , College of Psychology and Sociology, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

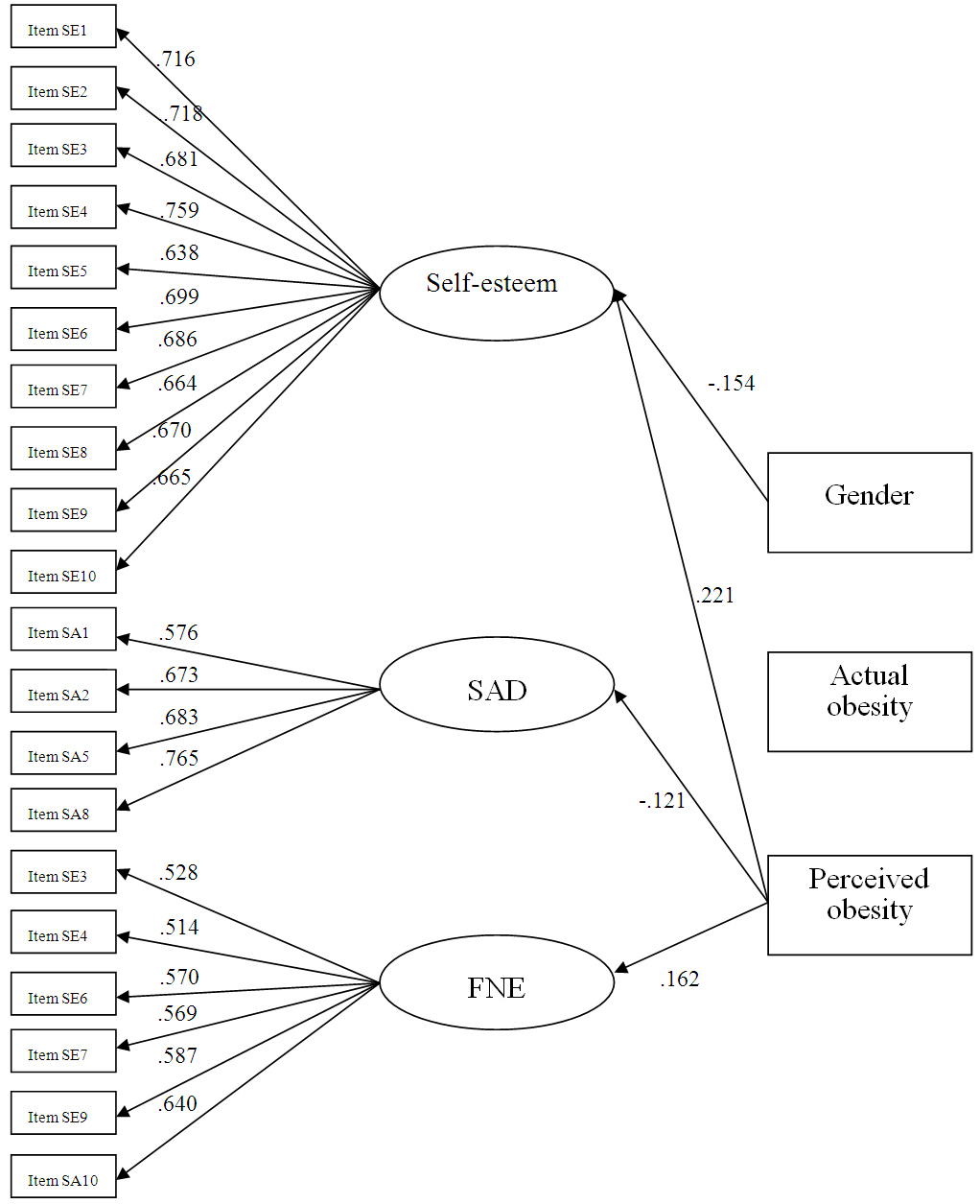

This study explored the relationship between obesity perception, obesity itself with self-esteem and social anxiety of obese adolescents using Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) model. 297 adolescents, who visited for regular health examinations at the Medical Examination Center of three hospitals located in Shenzhen, completed a battery of self-report questionnaires measuring obesity perception, self-esteem and social anxiety. Findings suggested that MIMIC model can be considered as a reasonable statistical method to invest the influencing factors of self-esteem and social anxiety for obese adolescents systematically. Gender predicts self-esteem, weight perception predicts self-esteem and Negative Evaluation (FNE), while body size has no effect on both of these two psychological traits.

Keywords: Weight Perception, Self-Esteem, Social Anxiety, MIMIC Model, Obese Adolescents

Cite this paper: Can Jiao , Ding Yan , Ting Wang , Weight Perception, Body Size, Self-Esteem and Social Anxiety in Obese Adolescents: A Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) Model, International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20160601.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Obesity is generally defined as excessive body fat that results in increased risk of morbidity and mortality (Ogden, Yanovski, Carroll, & Flegal, 2007). In developed countries and in many developing countries undergoing fast economic transitions, it has emerged as a worldwide epidemic and has become a major threat to public health (Caballero, 2007). In China in 2000, the prevalence of obesity was 4.37% among 13 to 15-year-old boys, and was 2.37% among girls (Ji, Sun, & Chen, 2004). Although China is at an early stage of epidemic obesity by and large, the prevalence of obesity in the urban population, particularly in coastal big cities has reached the average level of developed countries (Chen, 2008). The prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents has been increasing in parallel with adults. These trends are concerning because obese children tend to become obese adults, and childhood obesity is associated with a plethora of cardiovascular disease risk factors and psychosocial disorders, including low self-esteem and high social anxiety. The psychological effects of being overweight are thought to be more severe than the physiological costs (Pierce and Wardle, 1997), and sometimes obesity can lead to complex psychiatric disorders (such as anorexia nervosa) with fatal physical and mental health consequences. There is no doubt that obesity is an undesirable state of existence for an adolescent, for whom even mild degrees of overweight may act as a damaging barrier in a society obsessed with slimness (Strauss, 2000). Self-esteem refers to the evaluation of oneself (Rosenberg, 1965) and can be considered as a basic human characteristic related to self-awareness, emotions, cognitions, behavior, lifestyle, general health and socio-economic factors (Greenberg, 2008). Body dissatisfaction is linked with self-esteem and their correlation is more stronger than that for self-esteem and actual weight (Tiggemann, 2005). Social anxiety is defined as anxiety because of a concern about how one will be perceived by others (Leary & Kowalski, 1995). Social anxiety was significantly correlated with Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) and includes anticipatory anxiety, cognitive/somatic symptoms in social situations, and avoidance behavior when distress is chronic (Pinto & Phillips, 2005). Self-esteem and social anxiety, which can be considered as latent variables, have no scale and are represented through indicator variables. Considering that it is subsequently difficult to assess the overall effect of covariates using standard χ2 difference tests, there is therefore a need for more systematic statistical approaches to investigate these complex associations.Previous studies have rarely considered simultaneously these three variables to construct an integrated model. The purpose of this article was to test the validities of self-esteem and social anxiety questionnaires for obese adolescents and to generate a model that describes the relationship of covariates, including gender, weight perception and body size, with the latent variables and the inner relationships of latent variables. To better evaluate the self-esteem and social anxiety, we used Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) modeling, a special case of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to reach the aim. MIMIC models provide a better insight into the correlations between observed variables, latent variables and covariates. They have the advantage of investigating the associations between the covariates and latent variables but also detecting the direct associations between covariates and observed variables after controlling for the presence of latent variables.There are two hypotheses in this article: (1) The self-esteem and social anxiety, which used in this study, has good validity on obese adolescents; (2) Weight perception, not the body size, affects self-esteem and social anxiety of obese adolescents.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

- This study was approved by the ethical comity of Shenzhen University, meaning that the researchers followed the ethical protocol of the university. All adolescents gave written informed consent and were informed that they could stop at any time if they felt they were treated incorrectly.

2.2. Participants and Procedures

- A cross-sectional study was performed on 297 adolescents (106 boys and 191 girls) aged 8-16 years (10.79 ± 1.889), who visited for regular health examinations at the Medical Examination Center of three hospitals located in Nanshan, Futian and Luohu District in Shenzhen. All the participants were randomly selected from students of eight schools in the three districts from March to June 2011. All were Han Chinese, and had lived in Shenzhen for at least two years. Investigation information sheets were provided and informed written consents were obtained from the students after explanation. Weights and heights were measured by the dietician and children were asked to complete the self-esteem and social anxiety measure. Participants were informed both orally and in writing that participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Of 361 students who participated in the study, the data of 64 participants were dropped due to the high number of missing values. The final sample was composed of 297 adolescents (ages range from 8-16 years with mean of 10.79 ± 1.889 years; 106 girls and 191 boys), and was divided into two groups: normal weight group and overweight or obesity group.

2.3. Measures

- Body size. The BMI was calculated from measured height and weight to give an index of the degree of adiposity (Michielutte, Diseker, Corbett, Schey, & Ureda, 1984). Height and weight were measured with electronic scales, the participants wearing their school uniform without shoes and bulky outer clothing (eg, jumpers or jackets). All data were selected from a regular medical examination. The BMI can be computed by applying the following formula including height and weight: BMI=body mass/height2 (kg/m2). According to the body mass index reference norm for screening overweight and obesity in Chinese children and adolescents suggested by Group of China Obesity Task Force (Ji, 2004), participants were classified as standard weight, overweight or obesity.Weight perception. The participants were asked to answer “How do you think of yourself in terms of weight?” The possible responses were "very overweight", "slightly overweight", "normal weight", "slightly underweight", and "very underweight" (Antin & Paschall, 2011). It is different from another question: “Are you satisfied with your body?” The latter measures body satisfaction, while the former determinate the perception about their own weight. Due to the small number of the categories of "very overweight" and "very underweight", we collapsed categories into three ones: “underweight”, “normal weight” and “overweight”. We then created dummy variables for each response option. “Normal weight” served as the reference category for all analyses.Self-esteem Measurement. The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES) is a widely used self-report measure designed to assess the concept of global self-esteem. The RSES comprises ten statements. In this study, participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each statement on a four-point Likert scale ("strongly agree" to "strongly disagree"). Five items were positively worded and scored, while other five were negatively worded and reversely scored. A total scale ranging from 10 to 40 for each subject was obtained by summing all responses, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem (Chedraui et al., 2010). The RSES does not have recommended cut-scores for high or low self-esteem therefore classification into high or low self-esteem is not possible as a standard convention.Social anxiety Measurement. The Social Anxiety Scale for Children (SASC) was developed to assess children’s feelings of social anxiety (La Greca, Dandes, Wick, Shaw, & Stone, 1988). SASC includes ten items belonging to two factors: Negative Evaluation (FNE) and Social Avoidance and Distress (SAD). FNE contained six items that were characterized by a concern that other children would judge oneself in a negative manner. The six items were all from the group of items developed initially to tap fear of negative evaluation. SAD, the second factor, consisted of four items that were developed to assess social avoidance and social distress. These items are rated on a three-point Likert scale, ranging from “not a good indicator” (1) to “an excellent indicator” (3) of social anxiety.

2.4. Analyses

- Structure Equation Modelling (SEM) analyses were conducted in Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2001). Prior to the addition of the covariates, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed in order to establish a valid model. The MIMIC model is a special case of SEM and consists of two parts: a measurement model which defines the relations between a latent variable and its indicators and a structural model which specifies the causal relationships among latent variables and explains the causal effects (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996). The model was used to test the effects of covariates on a hypothesized sole-factor model.

3. Results

- In the first step, we performed CFA to test the global fit of the factor structure of self-esteem and social-anxiety to empirical data. The general fit of RSES was adequate: χ2=95.053 (df=35, P < 0.001), CFI=0.954, TLI=0.940, RMSEA=0.076[0.058,0.095]. The range of size of factor loadings is between .630 and .761. We performed a multigroup CFA in order to test the fit of the model in both normal weight group and overweight or obesity group at the same time.The fit indices showed adequate fit: (χ2=149.039, df=88, P<0.001; CFI=0.953, TFI=0.952, RMSEA=0.068 [0.049, 0.087]) The general fit of SASC was appropriate: χ2=85.332 (df=34, P<0.001), CFI=0.941, TLI=0.922, RMSEA=0.071 [0.053,0.090]. The range of size of factor loadings is between .518 and .766. The weak or moderate correlations between factors support the discriminant validity of the two sub-scales. In the same way, we also performed a multigroup CFA for SASC. The fit indices also showed adequate fit: (χ2=169.192, df=84, P<0.001; CFI=0.907, TFI=0.900, RMSEA=0.083[0.065, 0.101]).In the second step, we added the structural part of the model to the measurement model and estimated the MIMIC model. Gender, perceived obesity and actual obesity were used as covariates in the MIMIC model as shown (Figure 1). Before the estimation of the model fit, the binary correlations of study variables including latent variables and predictor variables were estimated. As indicated, self-esteem significantly correlated with gender and perceived obesity (r1 = -0.167, P1 < 0.001; r2 = 0.188, P1 < 0.001), whereas SAD only significantly correlated with perceived obesity (r1 = -0.116, P < 0.01). (Figure 1)In the first step of structural equation model testing, the fully saturated structural model was estimated. This model showed adequate degree of fit to the data (χ2=385.091, df=252, P<0.001; CFI=0.938, TFI=0.929, RMSEA = 0.042[0.034,0.050]). And then the influence of gender, age, perceived obesity and actual obesity on self-esteem and social anxiety was estimated simultaneously. The results showed that the estimation of the factor loading is in accordance with the estimation of CFA model for the measurement modeling. For the structure modeling, gender has significant negative effect (γ = -0.154, P = 0.001) on self-esteem and the group of participants did not influence any one of the latent variables. And weight perception has significant positive effect (γ = 0.221, P = 0.001) on self-esteem, and significant negative effect on FNE (γ = -0.162, P = 0.010).

| Figure 1. Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) model of variables relating to self-esteem and social anxiety in adolescents with obesity |

4. Discussion

- Results of CFA support the construct validity of the RSEA and SASC. The single-factor structure of RSEA and the two-factor SASC were confirmed in a relatively large adolescent sample. In addition to very good indicators of these models, factor loadings, i.e. indicator reliabilities, reveal the high representativeness of all the items concerning the underlying construct self-esteem and social anxiety.MIMIC modelling is an excellent approach to investigate the validity of a factor model in the presence of covariates, and is the recommended method for a sophisticated construct validation if a theoretically sound conceptual model regarding the different causal relations of indicators and constructs exists (Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001). A MIMIC model was created to investigate whether and how gender, weight perception and body size affected the predicted factor structure. This model was a very good approximation to the data. The patterns of associations with gender, weight perception and body size were tested simultaneously, and the final model also bolsters the construct validity. Two of the three latent variables are associated with weight perception and self-esteem is associated with gender too, but none of them links with the body size in our model.In summary, the described MIMIC model in Fig.1 highlights the necessity of systematic statistical approaches such as MIMIC modelling to be used when investigating the influencing factors of self-esteem and social anxiety for adolescents with obesity. Such observations underline the importance of testing latent variables simultaneously and taking into consideration the fact that some factors could influence the onset of others. Models such as the one developed here highlight the important associations between covariates and factors that may otherwise have been missed.Gender predicts only self-esteem and girls had significantly lower levels of self-esteem compared with boys. This results consistent with previous studies undertaken in Thailand (Wongpakaran, Wongpakaran, & Wedding, 2012) and other countries (Moksnes, Moljord, Espnes, & Byrne, 2010; van den Berg, Mond, Eisenberg, Ackard, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2010). Like other East Asian countries, males are expected to become a leadership role in the family or in society in China, while females are not so. At the same time, on account of participants are in adolescence, girls pay more attention to their appearance and negative weight perceptions are particularly common among young adolescent females (Neff et al., 1997; Strauss, 2000). So it is not surprising that young adolescent females show the lowest level of self-esteem.Weight perception predicts self-esteem and FNE but not SAD. However, body size has no effect on both of these two psychological traits. One possible explanation for the results is that their perception of obesity is an internal standard, whereas IBM is an external standard which is not familiar to obese adolescent in the present study. Misperceived overweight is prevalent among Chinese youth. Nowadays, 15% of high school students in the Chinese cities perceived themselves to be overweight (Zhang et al., 2011). Hence, it is necessary to build appropriate inner weight locals of control, especially in present China where characterizes as 'thin is beauty'. Applicable inner weight locals of control can facilitate psychological traits including self-esteem and social anxiety. Actually, obesity symptoms and psychological traits are interactive. Adolescent obesity perception usually increases the risk of body dissatisfaction and low self-esteem. In Portuguese adolescents, inaccurate perceptions of the need to diet, poorer self-perceived health status and potential social isolation of those who are overweight were found (Zhang et al., 2011). Therefore, strategies to prevent adolescent obesity and overweight must take into account a deeper knowledge of psychosocial issues in order to be able to delineate more effective programs for assessing and treating overweight teens. Moreover, the need for early identification, assessment and management adolescents who exceed a healthy weight for height, gender and age, which would enable us to start prevention and management of adolescent overweight and obesity earlier, thus decreasing the potential for associated medical and psychosocial problems (Fagan, Diamond, Myers, & Gill, 2008). To set up a reasonable internal fat locus of control, improve self-esteem, reduce social anxiety, so as to control obesity, and improve the psychological well-being.

5. Limitations and prospective

- Several limitations to our study should be noted. The sample size in both groups was small, which limits the generalisation of the findings and precludes sub-group analysis based on age and gender. New studies with larger representative samples are needed to assess more directly the currency of our findings. A longitudinal approach would be the ideal when investigating the direction of relationships between covariates and latent variables and this study has utilised data collected at a single time point. It is worth nothing that many overweight adolescents have already taken action to change (or at least maintain) their weight (Franklin, Denyer, Steinbeck, Caterson, & Hill, 2006), so their perception of obesity may also change after years. A previous study suggested that self-esteem in preadolescence (9 to 10 years of age) was not related to obesity while global self-esteem by 13 to 14 years of age was related to the presence of obesity. And obese children with decreasing levels of self-esteem demonstrate significantly higher rates of sadness, loneliness, and nervousness and are more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors such as smoking or consuming alcohol. Hence, enabling the formation of self-worth in early adolescence with obesity is crucial to ensure psychological healthy.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML